Developing East Palo Alto’s Ravenswood Business District means confronting a legacy of contamination

The story was originally published by the The Almanac with support from our 2024 Data Fellowship.

A sign warns of contaminated soil at a construction site in East Palo Alto.

Photo by Anna Hoch-Kenney.

Real estate in San Mateo County is among the most valuable in the United States. Even small parcels can fetch millions. Yet, in East Palo Alto’s Ravenswood Business District, acres of land sit empty, their potential unrealized.

At first glance, these vacant lots appear to be prime real estate — offering stunning views of the Diablo Range to the east and the Santa Cruz Mountains to the west, with the San Francisco Bay Trail hugging the area’s eastern edge. But beneath the surface, remnants of the area’s industrial past linger. Arsenic, lead, cadmium, volatile organic compounds, and oil contaminate the soil and groundwater, rendering much of the district uninhabitable until extensive remediation is complete.

Views of the Bay Trail from a vacant lot near the end of Fordham Street.

Photo by Anna Hoch-Kenney.

Wildflowers pop up on a vacant lot along Bay Road.

Photo by Anna Hoch-Kenney.

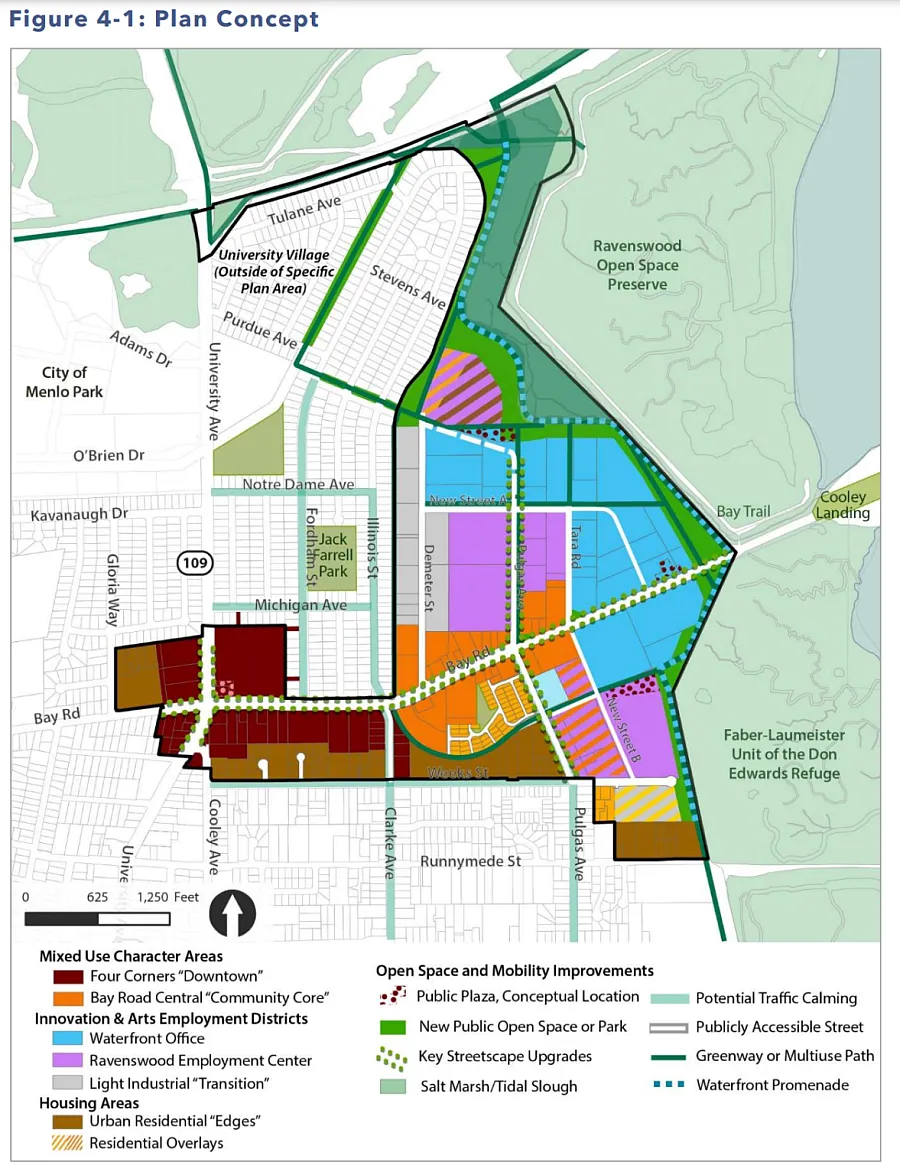

An illustration of the Ravenswood Business District Specific plan concept shows the development and infrastructure upgrades planned for the area.

Courtesy city of East Palo Alto

The city is now eyeing the Ravenswood Business District for redevelopment — offices, retail, open space and housing are all planned for the area, which city officials envision as East Palo Alto’s new “main street.” If built as proposed, the taxes generated by the new Ravenswood Business District Area Specific Plan — passed in December 2024 — could be game-changing for a city that has long struggled to balance its budget. It could also introduce much needed grocery and restaurant options, and provide more green space to city residents, who currently lack many of those amenities.

However, environmentalists, community activists, and residents fear that redevelopment, if not constructed with environmental remediation as a priority, may pose serious risks to human health. They believe city officials will prioritize economic development over the community. Once buildings are constructed on contaminated sites, they say that addressing potential issues that bubble up amid climate change, as groundwater rises beneath the sites, will become significantly harder.

Some city officials see rapid redevelopment of the area as the only real plan for cleaning up toxic sites that have languished for years, as cleanups are frequently accelerated when developers are interested in the land and bring in their financial resources.

A lot for sale at the end of Demeter Street in East Palo Alto on August 12, 2024.

Photo by Anna Hoch-Kenney.

East Palo Alto’s toxic legacy

One of residents’ biggest concerns as cleanups have lagged is that the pollution isn’t just lurking beneath the soil, but has already affected their health.

Data from the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment shows that asthma rates are about 40 percentage points higher than in neighboring cities like Palo Alto, Menlo Park and Atherton. The city is in the 80th percentile in the state for low birth weight — the rate of babies suffering from low birth weight in East Palo Alto is nearly double that in neighboring cities. Many health experts and activists link these health disparities to the decades of environmental contamination.

“Because the city had these kinds of toxic facilities running for so long, along with the history of contamination, we (in East Palo Alto) have just had a huge influx of cancer and asthma rates,” said Fili Zaragoza, an East Palo Alto resident and environmental campaign organizer for Youth United for Community Action, a grassroots organization that has fought for decades against pollution in the city.

Volatile organic compounds, which have been found in abundance in the contaminated sites in the Ravenswood Business District, have been linked to cancer, asthma and low birth weight, according to a U.S. EPA fact sheet on the contaminants.

Cade Cannedy, program director at East Palo Alto-based environmental justice nonprofit Climate Resilient Communities, said that cleaning up these contaminated sites is a step that needs to be taken to close the gap in health outcomes.

“There’s a lot of reasons for (the disparity in life expectancy), but part of the picture is the environmental injustices,” he said.

Cannedy said that East Palo Alto’s lower life expectancy is shaped by a combination of high asthma rates, respiratory conditions, and environmental risks like flooding and poor air quality in addition to the contamination present in the community. He explained that it is often hard to generate urgency around site cleanups when the contamination isn’t easy to link to specific health outcomes.

“Even if we can’t say exactly what percent of the life expectancy difference is due to any particular site’s presence in the community, we can say that the confluence of all these factors is driving this disparity and that injustice needs to be addressed,” he said.

Environmental injustices

For advocates like Cannedy and Zaragoza, the contamination isn’t just an environmental issue, but also a matter of racial and economic justice.

“With us being a primarily community of color, we are straight victims of environmental racism,” Zaragoza said.

Historically, cities like East Palo Alto — home to predominantly Black and Latino communities — have been disproportionately burdened by industrial pollution.

According to Kristina Hill, director of University of California Berkeley’s Institute of Urban and Regional Development, racist housing policies, such as redlining and blockbusting pushed both people of color and polluting industries to the peripheries of Peninsula cities — low-lying, unincorporated areas near the Bay, which were less regulated and closer to shipping routes.

“There are lots of places where (people of color) were excluded from living in the city by racist housing covenants,” Hill said. “They had to live at the edge of the city, often in unincorporated areas where they had fewer protections, like no city council, none of the money that was allocated to cities. … They lived in an area that was industrialized because nobody wanted the factories to be inside the fancier parts of the city.”

East Palo Alto is the youngest city in San Mateo County, incorporated in 1983 after a long battle for self-determination.

According to Zaragoza, contamination is concentrated in the young city in part because, immediately following incorporation, East Palo Alto needed to generate income, so to do so, it “made a few bad development choices.”

Following incorporation, Zaragoza said that the city took on much of the “dirty development” required to accommodate the Bay Area’s expanding population and tech industries.

As a city that still struggles to balance its budget, Zaragoza said he worries that East Palo Alto will once again make poor development decisions in the Ravenswood Business District out of financial necessity, potentially compromising community needs such as affordable housing and health.

What’s in the soil?

Data from the various state and federal agencies that regulate contaminated sites show that there are 62 contaminated (“open”) or formerly contaminated (“closed”) sites in the 2.5 square miles that make up East Palo Alto.

“That kind of density of contaminated sites is pretty unmatched in the Bay Area,” said Cannedy.

The 207-acre Ravenswood Business District is home to 17 open contaminated sites and eight closed sites, which may still have trace pollution in the groundwater and soil below the site.

“The reason that we don’t draw a super strong distinction between a closed site and an open site is that a lot of the closed sites are sites that have been closed without adaptations that make them resilient in the context of climate change,” said Cannedy.

Among the many contaminated sites in the district, two stand out: the former Romic Environmental Technologies site at 2081 Bay Road and the former Rhone-Poulenc site at 1990 Bay Road.

A notice of development hangs on the chain link fence surrounding part of the former Romic Environmental Technologies site on Bay Road in East Palo Alto on Feb. 13, 2025.

Photo by Anna Hoch-Kenney.

Bay Road Holdings, LLC, has proposed 1.3 million square feet of offices, retail and open space for the Romic site. Harvest Properties, Inc. has proposed a 1-million-square-foot mixed-use development with retail, community space, office and research facilities for the Rhone-Poulenc site. Neither developer returned this news organization’s request for comment.

For decades, the Romic has been the face of contamination in East Palo Alto. The 12.6-acre site had been used as a hazardous waste management facility since the 1950s. Romic, which took ownership of the site in 1964, processed solvents, inks, antifreeze and fuels there until the plant was shut down through community action, led by YUCA, in 2007.

The company’s 43-year operation was plagued with citations and violations. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Romic was cited for discharging cyanide into East Palo Alto’s sewage line, fined $100,000 for an incident where a worker was severely injured by toxic fumes and fined $849,500 for mislabeling chemicals, storing chemicals in improper containers, exceeding the capacity of hazardous waste containers, blending incompatible chemicals in the same container and modifying equipment without authorization. Despite these violations, Romic continued operating for over a decade without securing a permit renewal.

The smokestacks and cooling towers at the former Romic Environmental Technologies sites in East Palo Alto in 2008.

Courtesy U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

A galvanizing moment for the East Palo Alto community and YUCA, which had already been working to shut down Romic since 1994, came in June 2006 when a 4,000-gallon mixture of various volatile organic compounds reacted inside a tanker truck on the site. A large plume of chemicals erupted from the truck, spreading a fine mist of sticky, black chemicals over the Romic site, Bay Road, nearby homes, a PG&E substation and the adjacent marsh.

At the time of the incident, Lorraine Holmes, a longtime resident of East Palo Alto, was outside her house. She became ill after exposure to the chemical plume.

“I was in my backyard watering plants at the time. It took my breath away,” Holmes told Palo Alto Weekly in 2006. “My doctor diagnosed chemical burns in my throat and esophagus. It was all the way back to my tonsil area.”

Naomi Goodman, a retired environmental professional with over 40 years of experience characterizing chemical contamination, said that plumes of volatile organic compounds such as trichloroethylene, benzene and vinyl chloride extend up to 80 feet deep in the groundwater and soil at the Romic site. Investigations conducted between 1985 and 2020, also revealed the presence of metals, polychlorinated biphenols (PCBs), dioxins and furans.

“(The site) accepted drums of God knows what kind of solvents,” said Goodman, who has been working with the Sierra Club to advocate for cleanup efforts in East Palo Alto. “They treated them, and, in some cases, stored them in unlined impoundments. (The site is) still highly contaminated.”

Goodman said prolonged exposure to these chemicals could pose serious health effects.

“VOCs, some of them are cancer-causing, like benzene, others have non cancer health effects, such as damage to the kidney or liver, reproductive health impacts like low birth weight, neurotoxicity, it really depends what chemical you’re talking about,” she said, adding that certain VOCs can cause respiratory problems, as well as nausea and headaches.

While Romic has long been the most well-known contaminated site in East Palo Alto, activists are also turning their attention toward the other potentially toxic sites throughout the business district and surrounding region.

Other contaminated sites in the Ravenswood Business District

Piles of cars are visible over the fence at Infinity Auto Salvage on Bay Road in East Palo Alto on Feb. 13, 2025.

Photo by Anna Hoch-Kenney.

Climate Resilient Communities and other local environmental groups have developed a prioritization matrix to evaluate which contaminated sites pose the greatest threat to the community. The matrix, informed by community input, scores contaminated sites based on their proximity to residential areas, severity of contaminants and their susceptibility to flooding.

According to this matrix, the former site of the Rhone-Poulenc pesticide manufacturing plant, scored slightly higher than the Romic site in terms of potential risk.

“They stored a lot of drums out there — the drums leaked and the area flooded with high tides, and it spread a lot,” said Goodman.

Of most concern is the arsenic, which the Rhone-Poulenc site left “under buildings” and “has never been remediated,” Goodman said, adding other heavy metals on the site, such as lead and cadmium, mercury and selenium, were also concerning.

“The levels they left on site are just really high,” she said.

Arsenic contamination has been found beyond the site, including nearby industrial properties, a portion of the PG&E substation and several residential properties. The contaminated area extends 23 acres, and is regulated as a unit.

“You go down into the groundwater, and there’s milligrams per liter of arsenic, which is just an outrageous amount,” Goodman said.

As environmental and health research progresses, arsenic is increasingly being ranked as a more hazardous pollutant than previously thought. Goodman and other environmentalists worry that the cleanup standards set for the site in 1991 may not be as protective as the existing ones. Goodman pointed to links between arsenic exposure and cancer, cardiovascular disease, skin lesions, low birth weight and diabetes.

Regulatory agencies say sites are contained

A sign warns of contaminated soil at a housing development construction site on Weeks Street in East Palo Alto on Feb. 13, 2025.

Photo by Anna Hoch-Kenney.

Representatives from both the California Department of Toxic Substances Control and the Regional Water Quality Control Board — the two state agencies that regulate cleanups in the Ravenswood Business District — said that current remediation and capping efforts are sufficient to prevent exposure.

The Romic site is also regulated federally by the U.S. EPA, but the agency declined to comment. President Donald Trump has ordered a prohibition on external communications from the agency.

“It is important to note that the community is not impacted by the contamination at these sites,” said Russ Edmonson, a representative from the DTSC, in an email.

Ross Steenson, a representative at RWQCB, said that of the sites his agency oversees in East Palo Alto, do not currently pose a health risk to the public.

City officials share the same confidence. The updated Ravenswood Business District Area Specific Plan, officials said, is sufficient to protect residents from hazardous pollution as the area is built out.

The specific plan requires developers to check for contamination before they start building and take steps to keep workers, residents and future occupants safe, said Amber Sharpe, a project manager at the consulting firm David J. Powers, which developed the environmental impact report for the city’s specific plan, at the December meeting where the plan was approved. The plan also lays out rules for dealing with hazardous materials so that redevelopment doesn’t worsen existing pollution.

The Romic site in 2017 after undergoing “aboveground clean closure,” where all surface infrastructure was removed and the site capped with concrete.

Courtesy U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The Romic site in 2017 after undergoing “aboveground clean closure,” where all surface infrastructure was removed and the site capped with concrete. Courtesy U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

According to Edmonson and Steenson, both the Romic site and the Rhone-Poulenc sites have received “aboveground clean closure” designations, meaning all surface infrastructure from the polluting land use was removed, and the sites were capped with concrete to prevent exposure.

Monitoring data shows that contamination at the Romic site is not spreading beyond the property’s boundaries. Groundwater tests also show that the arsenic contamination is contained within its borders.

Though remediation is underway, some of these sites, including Romic and Rhone-Poulenc, have remained contaminated for decades. Activists argue that remediation measures like capping and containment, which still leave some measure of contamination underground, are not enough for the community, which has suffered the health and environmental impacts of the exposure, and deserves a true cleanup that is long overdue.

“Even generously, I feel like it’s difficult to justify a contaminated site sitting there for a decade — let alone two, let alone three, let alone six,” said Cannedy. “There are people that have lived and died in East Palo Alto … before a site has been cleaned up. They’ve lived in the shadow of it for literally their entire life.”

A March 2023 U.S. EPA memo estimated that under current conditions, Romic’s enhanced biological treatment system will achieve the agency’s cleanup goals within 10 to 19 years. But environmentalists like Goodman worry that even capped sites like the Rhone-Poulenc could still pose long-term risks, especially if the property floods, concrete cap cracks, or groundwater pushes up from underneath the site.

Redevelopment: A path to cleanup or a risk?

A notice of development hangs on a wall in front of 1175 Weeks Street in East Palo Alto as the pavement in front of the property is submerged by flood waters on Feb. 13, 2025.

Photo by Anna Hoch-Kenney.

One of the issues that activists are facing is that remediating contamination is often inextricably linked to redevelopment, which is why the Ravenswood Business District Area Specific Plan update process has sparked this renewed interest in the contaminated sites in the city.

Edmonson, of the Department of Toxic Substances Control, said that because state and federal law follow the “polluter pays principle,” those responsible for contaminating the site are responsible for cleaning it up. If the property has changed hands, the new owner takes responsibility. If there is no viable responsible party, cleanup is sometimes funded by public money, though that is rare.

Cannedy said that under the current regulatory structure, the state agencies are not set up to be responsive to community health concerns.

“It’s ultimately up to redevelopment projects to decide if, when and how they want to address contamination,” he said.

A housing development construction site on Weeks Street in East Palo Alto, where signs warn of contaminated soil, on Feb. 13, 2025.

Photo by Anna Hoch-Kenney.

Hill said slow cleanups aren’t just a result of cost or complexity, but also a result of state agencies not wanting to push for remediation efforts due to “fear of lawsuits from the property owner.”

”The property owner can sue or just delay, and write threatening letters from their attorneys to the state,” she said. “It slows everything down because the state isn’t willing to be as aggressive.”

In an ideal world, Hill said, the best policy would be to clean up the sites as quickly and entirely as possible before anything is built there.

However, development proponents argue that delaying projects also delays remediation, since cleanup efforts often depend on investment from developers.

“I think we have to take contamination seriously and be very concerned about this, but by not building, it’s not as if these problems are magically going away,” said Vice Mayor Mark Dinan, who joined the council in December 2024. He has been a vocal advocate of development in East Palo Alto. Other city council members did not respond to requests for comment.

“If somebody is going to drop $300 million developing a site, they are going to remediate it, whereas if it stays empty, nothing is going to happen and the problem will continue,” he added.

Dinan, who lives near the district, said contamination needs to be taken seriously, but argued that the city lacks the funding to conduct soil and groundwater testing on its own.

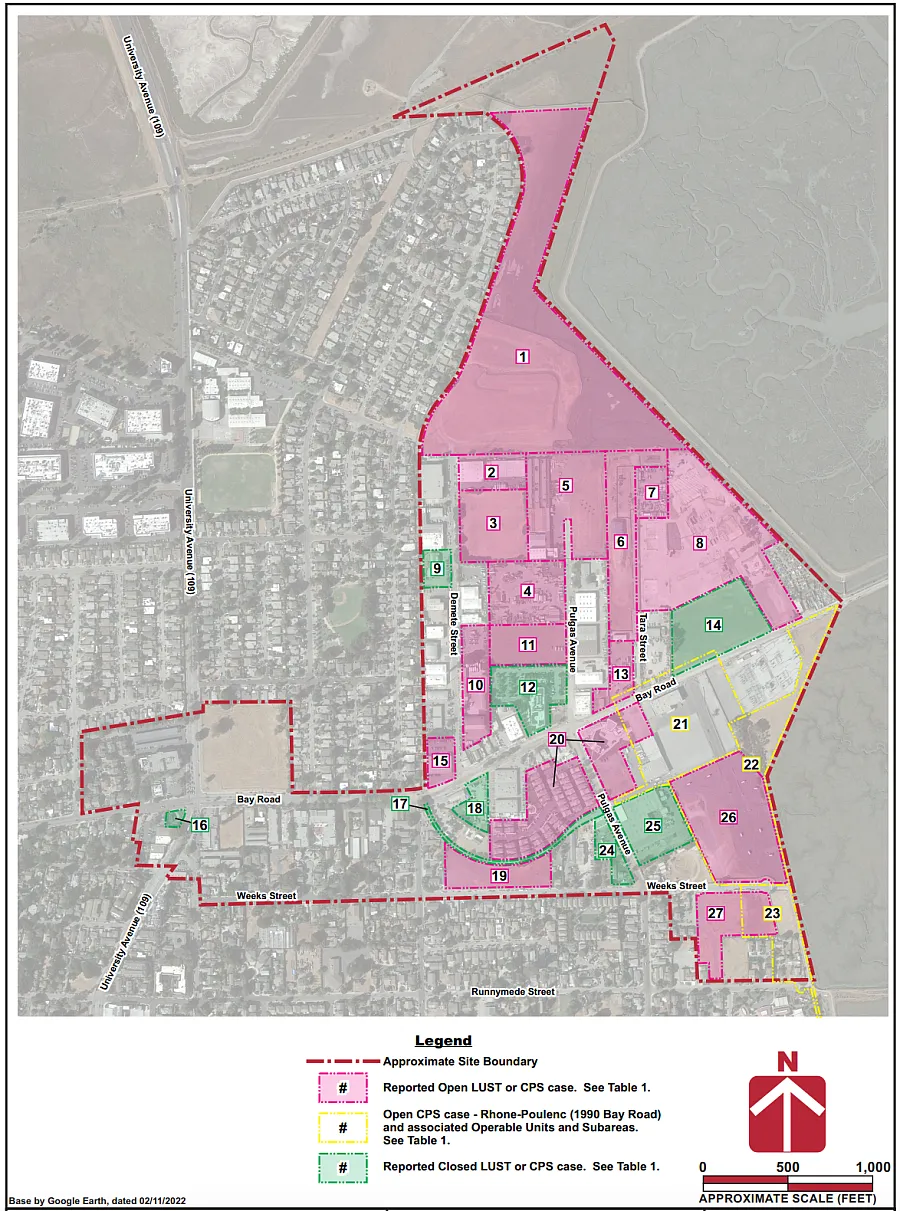

A map developed by the city of East Palo Alto during the Ravenswood Business District Specific Plan update process shows the extent of deed restrictions, also known as land use covenants, in the district.

Courtesy city of East Palo Alto.

“Right now, there’s nothing being done except the bare minimum, but if we want more done, it’s going to require investment,” he said. “The contamination may continue to spread in the groundwater, and by not building on them, it’s not like this problem isn’t going to continue to be a problem, … we just won’t have the resources to address it adequately.”

Steenson, of the Regional Water Quality Control Board, said the agency oversees contaminated sites across the Bay Area and that sites are often redeveloped. Once a site has been closed, it is generally considered safe to build on.

If removing all pollution from the site isn’t feasible, the agency can impose deed restrictions on the land to prevent it from being used for “sensitive” purposes such as housing, schools, hospitals and senior facilities, he said.

But environmental advocates argue that redevelopment alone won’t ensure a thorough cleanup, especially as past remediation plans may no longer meet today’s health standards. They also warn that climate change and rising groundwater could spread contaminants beyond the boundaries of deed-restricted sites, reaching areas with fewer protections.

“Since the city deferred a lot of stuff to individual projects, we are going to have to watch this like a hawk,” Goodman said. “Every time (a development) is proposed, we’re going to have to dive into their data.”

Cannedy said activists are not opposed to development of the area, but they want it done responsibly.

“It would be better if these empty sites were cleaned up and put toward a productive use for the community,” said Cannedy. “But if someone is going to stand to make a bunch of money redeveloping these sites, the least they could do is clean them up, and do so to a degree that is maximally protective of human health.”

Pushing for a cleaner future

A rainbow appears over Bay Road in East Palo Alto on Feb. 13, 2025.

Photo by Anna Hoch-Kenney.

Though activists turned their attention back to the contamination during the Ravenswood Business District Specific Plan update process, it is unclear how much influence the city or the council actually have to speed up remediation.

Much of that authority lies with state and federal agencies that control the contaminated sites, such as the California Department of Toxic Substances Control, the Regional Water Quality Control Board and the EPA.

While these agencies occasionally impose enforceable cleanup timelines, state law doesn’t require them — or the owners of the contaminated sites they oversee — to remediate within a specific timeframe.

Activists want to change that.

“Part of the thing we are interested in mobilizing people around is having a timeline for the remediation of these sites,” said Cannedy. “It’s hard when people are asking you, ‘Is this going to make me sick?’ We don’t know. Maybe not, probably not. … But that risk is only being borne by specific communities, and that is the definition of an injustice.”

To push for stronger oversight in East Palo Alto, Belle Haven and North Fair Oaks, Climate Resilient Communities and YUCA have banded together with other local community organizations — Belle Haven Community Development Fund, Nuestra Casa, Belle Haven Empowered — to form a taskforce called the Peninsula Accountability for Contamination Team. SPUR, a San Francisco-based public policy research nonprofit, advises the group on policy matters.

A bicyclist carefully makes their way around the edges of a flooded section of Weeks Street in East Palo Alto on Feb. 13, 2025.

Photo by Anna Hoch-Kenney.

“We’ve had people increasingly asking us about the contamination in the community,” said Cannedy. “I think the (impetus for forming PACT) was the Ravenswood Business District project and all the conversations we’ve had throughout that process. … We wanted to be responsive to their concerns.”

Sarah Atkinson, hazard resilience senior police manager at SPUR, said that while cities have little direct authority over the cleanup of contaminated properties regulated by the government, they are not completely powerless.

“At the moment there is a development proposal, cities and the community have an opportunity to ask for stricter or faster cleanup as part of the development negotiation,” she said. “It is difficult for cities to take proactive action like this. I think the best way to expedite remediation is for community members to get involved and document any contamination issues or public health issues.”

PACT is now working to launch a community health assessment related to contaminant exposure, host public town halls to share information on site cleanups and advocate for legislation, such as California Assembly Bill 1102, which would require groundwater rise and sea level rise risk assessments for developments near the Bay or ocean that sit within 1,000 feet of a contaminated site.

Cannedy said the community shouldn’t have to wait indefinitely for cleanup, noting that the Romic site has been vacant for 18 years with no clear end in sight. If that’s unacceptable, he said, “then we need to be putting more pressure on regulators.”

“The state really needs to be stepping up to address this contamination on a scale that’s commensurate with people’s life experiences,” Cannedy said.

Cannedy, Goodman and Zaragoza said their organizations will continue to monitor cleanup efforts in East Palo Alto and the Ravenswood Business District — and won’t let the community slip through the cracks.