Disability agency blasts Sonoma County jail’s treatment of mentally ill

This article was produced as a project for the California Data Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Two deaths in one jail in one month: How are we treating mentally ill inmates?

Last August, Anne Hadreas toured Sonoma County’s main jail in Santa Rosa to check on the treatment of inmates there.

Hadreas is an attorney for Disability Rights California, an agency that monitors conditions for mentally ill and disabled people in jails, state hospitals and other facilities. She’s visited lots of those facilities, but what she saw in Sonoma County still came as a shock.

When Hadreas and several other attorneys got to what the jail calls its mental health module, they were confronted by highly delusional inmates screaming and crawling on the floor.

“Some of the inmates were so disoriented and/or psychotic they were unable to converse with us,” says the DRC team’s report on the visit, made available to KQED in advance of its release Monday.

“We were really struck by the fact that people were incredibly acute in their need,” Hadreas recalled in a recent interview. “Higher than we’ve seen in units that are licensed designated hospital units. Something was wrong here.”

Hadreas said the case of one woman in particular stood out.

Medical records showed the woman came to the jail with a long history of being hospitalized for bipolar affective disorder, “often for weeks or months.”

In the summer of 2015, the DRC report says, the woman was confined to the jail’s mental health module several times after being arrested on a series of misdemeanor charges: disturbing the peace, trespassing and “peeking” — that last one being a peeping-tom offense.

Despite her history and the fact she was in distress, the DRC report says, at one point the woman went an entire week without being seen by mental health staff. During one stay, the woman “tore up her cell and flooded it,” the report says. Jail staff then turned off the water in her cell. After that, the DRC report says, the woman was found “‘bailing urine out of her toilet’ with her bare hands and drinking out of the toilet.”

It was obvious, the report says, that the woman “should have been transferred to a facility that could better meet her needs.”

The DRC’s report says the woman’s treatment, or lack of treatment, was part of a pattern of inadequate mental health care in Sonoma County’s main jail — a facility where nearly 40 percent of inmates locked up last year were reported to be mentally ill.

The DRC team also found that clinical staff administered involuntary injections of powerful, long-acting psychiatric drugs to inmates in routine violation of the strict requirements of state law. And the report says that many inmates in the main jail are held in what amounts to isolation, a situation that both complicates treatment for mentally ill people and makes their medical condition demonstrably worse.

In a formal response, as part of the report, Sonoma County officials challenged the suggestion that the unidentified woman mentioned in the report should have been treated at another facility.

“A review of this inmate’s chart shows that while at times she was mentally unstable, she was treated and cared for appropriately at the jail,” the response says.

The county says it has already taken steps to correct procedures regarding involuntary injections and that long-acting drugs are no longer being used to treat inmates on short-term holds. County officials also say many of the problems the DRC report identifies will be solved by the construction of a new $48 million mental health facility at the jail.

Restraint chairs in Sonoma County main jail’s mental health module. (Lisa Pickoff-White/KQED)

The conditions the DRC report found in Sonoma County’s main jail are a reflection of what mental health experts say is a disturbing reality nationwide: After decades spent “deinstitutionalizing” the mentally ill — removing them from settings like state hospitals in favor of community mental health facilities that have rarely been adequately funded — correctional facilities are now de facto treatment centers for those suffering from acute psychiatric disorders.

A 2010 study found that in California, nearly four times as many mentally ill people were in jails and prisons than in hospitals.

The report, produced by the National Sheriffs’ Association and Treatment Advocacy Center, said that “in historical perspective, we have returned to the early 19th century, when mentally ill persons filled our jails and prisons.”

Experts say conditions like those in Sonoma County show jails are simply the wrong place to treat the mentally ill.

“The sheriff is receiving most of the people on the street with serious mental illness,” said Terry A. Kupers, an East Bay psychiatrist and expert witness on the treatment of people with mental illness in jails and prisons. “The jail was not designed for treating people with mental illness. The person is in jail because they’ve been charged with a crime, and then the sheriff is stuck providing mental health services. Rarely are there adequate funds to do that.”

Sonoma County correctional and behavioral health staff agree that it’s challenging to meet the needs of such a large and acutely mentally ill population.

One of the toughest problems, they say, is getting people the treatment and medications they need. People with mental illness frequently do not want to admit that they are ill, said sheriff’s Lt. Mike Toby, who supervises the main jail’s three mental health units.

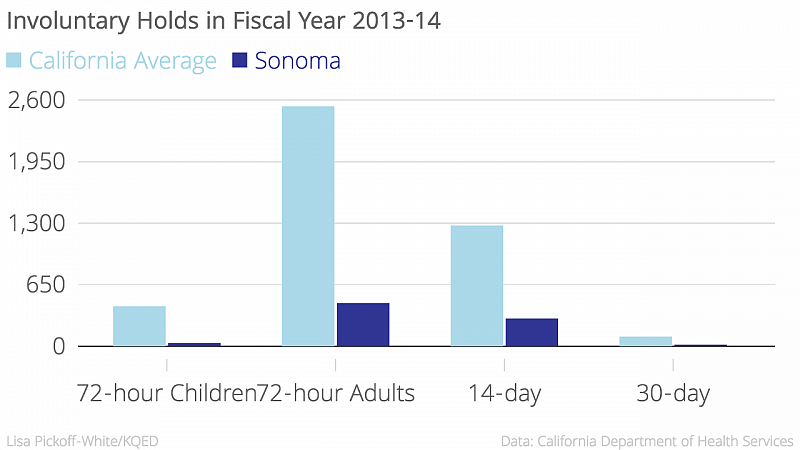

But jails are allowed to medicate inmates against their will only if the jails follow a strict set of procedures outlined in state law. The process includes first detaining an inmate on an involuntary 72-hour psychiatric hold, commonly known as a 5150, then getting a court’s sign-off on a petition finding that the inmate is too incapacitated to grant informed consent for medication.

The DRC report says that the Sonoma County jail’s process violated the legal requirements before administering involuntary injections. The practices were “illegal and must be stopped immediately,” the report said.

In the case of the woman who was found drinking from her toilet, mental health staff at the jail involuntarily injected her seven times during a 10-week period with several strong antipsychotic drugs used to treat bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and other conditions. The effects of some of the medications can last for four to six weeks.

But the DRC investigation found jail staff failed to seek a 5150 hold first, as required by law. And the DRC’s Anne Hadreas says that by using such long-acting drugs, the jail denied the woman essential legal rights.

“Normally, we have a right to refuse, and any person, even someone who’s been found to lack capacity, has a right to go to court,” Hadreas says. “But what happens if I go to court and I appeal that and I’ve already had a shot? I can’t remove that medication from my body. So for another month I’m still being medicated.”

In its response to the DRC report — and in a revised policy dated May 10 — the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office says it has changed its policies to ensure that mentally disturbed inmates are placed on 5150 holds before steps are taken to administer drugs involuntarily.

The sheriff’s office and county Behavioral Health Division “are committed to administering medications in the most appropriate and safe manner possible,” the response said.

Lawyers, advocates, correctional officers, inmates and their families often use the same phrase to describe the situation of mentally ill inmates in jails like Sonoma’s: “Warehoused.”

Kupers, the East Bay psychiatrist, says that medication alone will not help mentally ill people become well. That lack of treatment and frequent isolation leads mentally ill inmates to act out even more, he said.

The bipolar woman who flooded her cell and drank from the toilet was being involuntarily medicated, but still behaved erratically. Her impairment was so severe that a court later appointed a conservator to make care decisions for her.

“In truth, the unacceptable behaviors are essentially a protest against terrible conditions,” Kupers said. “But that’s not how the staff see them. So they see them as an uncooperative inmate or prisoner. And they give them more medication and then we get the sedative effect, the zombie effect.”

Beyond drugs, what sort of treatment do mentally ill inmates get in the Sonoma County main jail?

Psychiatrists see about 20 inmates a day, according to Sonoma County Mental Health Program Manager Jo Benwell, who works in the main jail. But even the most acute patients receive visits from a psychiatrist only about two to three times a week, she said.

The conditions for therapy in the jail’s mental health module are far from ideal, according to the DRC report, with inmates often required to speak to mental health staff through small slots in cell doors.

Benwell says staff focus on providing immediate support instead of focusing on deeper-seated psychological issues.

“You know, they don’t necessarily look at that issue with their parent 20 years ago,” she said. “We really need to help them, support them, with the legal process, which is very anxiety-producing.”

The Disability Rights California report also highlights the isolation of inmates in single cells in the Sonoma jail. While the facility meets the minimum state standard for outdoor recreation time — at least three hours a week — the report notes that some inmates reported being released from their cells for just 30 to 45 minutes a day.

The report calls that practice “extreme isolation” that can be especially harmful to mentally ill inmates.

The document briefly describes one man with bipolar disorder who was booked into Sonoma County main jail’s mental health module after violating parole. He was moved into a “step-down” unit, one designated for inmates who are not acutely mentally ill but not ready to be reintegrated into the general population. Inmates are still isolated in single cells in the unit.

The man repeatedly told mental health staff that the isolation was worsening his condition. In one request he wrote: “This is really not good for my mind. … I’m overwhelmed by this, which is causing me to not sleep, to feel agitated, powerless, depressed and confused. Please help me?”

Mental health staff told him that he was “doing well” and with “continued good behavior” he might eventually be placed in the general population, where he would have more access to outside areas and human interaction. But, the DRC’s Hadreas says, his condition only deteriorated in isolation.

The DRC’s report notes the jail is trying to increase the amount of time inmates spend outside their cells. For instance, the jail has added low partitions to a day room in the main jail so that higher- and lower-security inmates can be released at the same time without mixing together.

“We’ve spent probably close to $2 million in facility modifications so that we can improve the socialization of that particular population,” said Assistant Sheriff Randall Walker.

Hadreas lauded the sheriff’s department’s “creative approach” to modifying existing jail modules to help more inmates have access to time and space outside of their cells.

Lt. Mike Toby supervises the Sonoma County main jail’s three mental health units. He’s standing in a unit being renovated to give inmates more outside-of-cell time.

DRC also praised the jail’s placement of accessible cells throughout the facility, which keeps people with physical disabilities from being segregated.

The report commended the group therapy and anger management programs offered in the step-down units as well.

During a tour of Sonoma County’s main jail earlier in May, Walker said that the inmate population — which averaged 998 a day in 2015 — included about 400 mentally ill inmates. He said 58 people were housed in the jail’s mental health module and another 163 people were in the step-down units, with the rest spread throughout the general population.

He says the number of mentally ill inmates has soared over the past 25 years.

“When we opened in 1991 there were 13, and that 13 encompassed the more acute and the less acute,” Walker said.

The jail’s spending on psychotropic medication testifies to the change. During the last five years, the amount spent on such drugs increased by 322 percent, according to state data — the largest increase for any county in the state.

Walker said those numbers show that the county is doing a good job.

“Sonoma County is very good in diagnosing mental illness and addressing needs for the mentally ill,” he said. “So you have more people coming into custody, taking medication. And I think it’s a cultural shift here, where the stigma that may follow someone in some of the more rural counties isn’t as strong in Sonoma County.”

Benwell agreed that the increase was due to a growing population, and a population more used to taking medications.

“That might just be an antidepressant, or, you know, Benadryl, or something for anxiety,” she said.

California law requires jail officials to transfer mentally ill inmates to outside facilities for treatment when necessary. Such treatment, inside jail and out, is mandated to restore an inmate’s mental capacity so they can answer to the charges against them.

But records show that, even in dire cases such as the mentally incapacitated bipolar inmate who drank from her cell toilet last summer, Sonoma County rarely transfers inmates. According to state data, Sonoma County reported just one inmate per year getting inpatient care in outside facilities from 2010 to 2015.

Sonoma County jail’s correctional and mental health staff say they’d prefer mentally ill inmates receive treatment outside of jail, but argue that a broken system leaves them with few options.

One major problem, the county said in its response to the DRC report, is that it can find no outside psychiatric hospitals or facilities willing to treat its inmates.

Randall Walker, the assistant sheriff, says other treatment options are tough to find. He says it’s very hard for someone who hasn’t been charged with a felony to get into a state hospital for treatment, and even if a state facility accepts an inmate, a transfer can take three to four months.

“If [we] can’t house a person safely, then we try to find those other options,” Walker said.

Sonoma County Mental Health Services Director Mike Kennedy said that the county is doing the best it can with the resources allotted to it.

“What we’re stuck with is having to do the most humane treatment that we can in settings that aren’t set up to do it,” he said. “Most psychiatric hospitals won’t accept jail inmates. So, right there, that option, we don’t have it.”

As a Sonoma County public defender, Karen Silver represented mentally ill defendants for decades. She says that except for inmates sent to state hospitals, she has never seen someone leave the Sonoma County jail for outside treatment.

“I’ve never seen a person charged with a serious crime ever be diverted to the mental health system for the temporary purpose of getting them back to competency,” she said.

People charged with misdemeanor offenses have an even harder time getting treatment, Silver said.

“I’ve actually told people, families, that have kids in the system that are just charged with misdemeanors that you need to go to the prosecutor and say that you felt your life was threatened, that you need to verbally make this into a felony so that the person gets sent to the state hospital and gets treatment. Because they can always come back here and we can reduce it to a misdemeanor,” she said. “There was no doubt that the state hospital treatment was better than what the jail was able to do.”

Sheriff’s Lt. Toby, who supervises the main jail’s three mental health units, said that many people charged or found guilty of misdemeanors are trapped in a kind of limbo. They are too mentally ill to stand trial and don’t improve enough to make it to trial.

But Sonoma County says things will get better.

In November, Sonoma County received a $40 million grant from the state to build a new wing of the jail for mentally ill inmates. The current facility is not overcrowded, but officials said that 72 new beds in the facility will provide a better place to treat mentally ill inmates and those with substance abuse problems.

“Our biggest challenge is just space to program, so that we’re not trying to talk to people through doors and things like that,” Assistant Sheriff Walker said.

Most of the new unit will be used for treatment to restore inmates’ competency to stand trial.

But experts on the mental health of inmates say that’s not the way to go.

The DRC’s Hadreas compares building new mental health treatment facilities in jails to building more on-ramps to highways: The ramps lead to more traffic on the roads, and the jail facilities lead to more mentally ill people becoming incarcerated.

Psychiatrist Kupers says money spent on new jail facilities would be more effectively used for programs outside the jail, such as mental health courts, diversion, therapy and even vocational programs.

“Without that additional assistance, you’re setting people up to fail and fail. And I would say ending up in jail is a failure of the system,” Hadreas said.

Kennedy also sees a systemwide problem. He says part of the blame lies with hospitals for closing down psychiatric treatment centers.

“I don’t think for cancer you would refuse this,” Kennedy said. “It’s a huge problem that needs to be dealt with on a state and federal level.”

Hadreas agrees, saying state officials and agencies — from Gov. Jerry Brown to the Board of State and Community Corrections, which oversees county lockups — must find more effective ways to address mental health challenges in the jails.

“It’s something that certainly the BSCC, the governor, the Department of Mental Health can look at from a higher understanding and say, ‘What’s going on here? Can we rework this money in a way that’s actually helpful for people?’ ”

[This story was originally published by KQED.]

Photos by Lisa Pickoff-White/KQED.