Disabled Florida teen stuck in jail purgatory may get treatment

This article and others to come are produced as part of a project for the National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

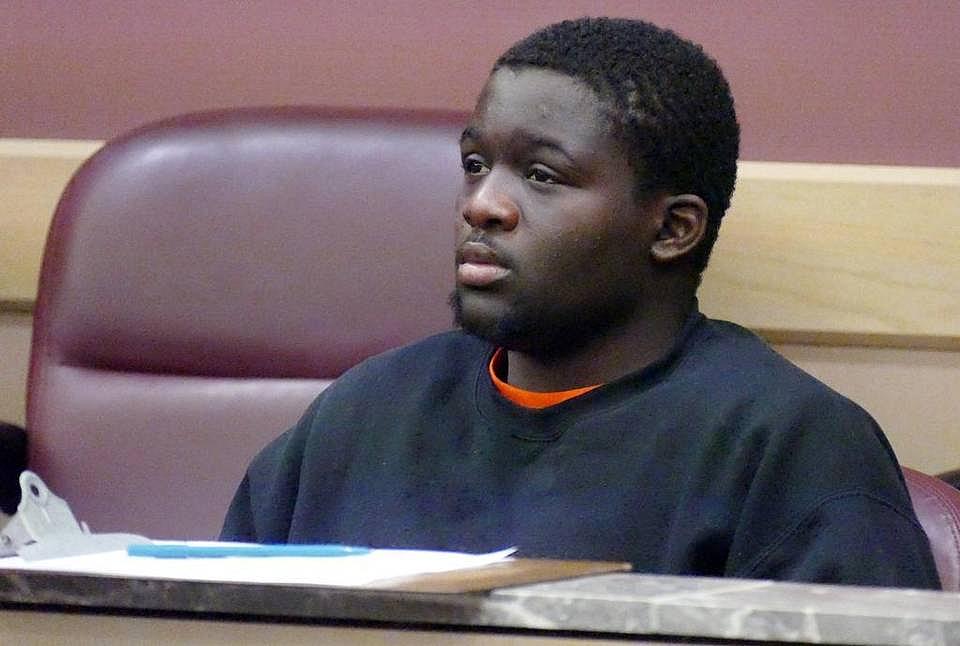

Keishan Ross sits through a hearing before Judge Michael Orlando on Feb.17, 2017, to determine where he will end up next. The intellectually disabled youth is currently being housed at the Broward Regional Juvenile Detention Center, where he isn’t treated for his conditions and where he rages inside his cell. EMILY MICHOT emichot@miamiherald.com

Florida juvenile justice administrators, hoping to find a home for an intellectually disabled teen who has spent most of his adolescence bouncing between juvenile jail and a mental health program that cannot help him get better, were planning to meet Tuesday with counterparts at other state agencies that deal with troubled kids. They said there was one thing stopping them: a Broward judge’s gag order.

Last week, Broward Circuit Juvenile Judge Michael Orlando ordered the Department of Juvenile Justice not to discuss the teen, 17-year-old Keishan Ross, with the staffs of psychiatric hospitals or drug treatment centers that might be considering admitting him. DJJ said Tuesday the order was just broad enough that it feared a staffing — a discussion with other agencies to go over treatment options — might violate it.

The agency asked Orlando to lift the order so administrators could meet in the afternoon with other agency heads.

Orlando declined to lift the gag order. The judge had signed the order following a hearing last week in which Keishan’s lawyers at the Broward Public Defender’s Office accused a DJJ probation officer of sabotaging an agreement they had reached with a Fort Lauderdale psychiatric hospital. The hospital was going to admit Keishan for a battery of tests to determine his intellectual capacities and the severity of his mental illness. But hospital administrators changed their minds, the lawyers said, after DJJ described him as violent and remorseless.

This child has been in the system since he was 10 or 11 years old, and [DJJ] has not been aggressive in getting the services the child needs, or identifying the services he needs. Gordon Weekes, head of the Broward Public Defender’s Office’s juvenile division

Keishan was the subject of a story in Tuesday’s Miami Herald. He remains at the Broward Regional Juvenile Detention Center, though he has been declared incompetent to stand trial more than a dozen times, due mostly to his intellectual disability. While at the lockup, Keishan rages, screaming and banging his fists against his cell door.

“This child has been in the system since he was 10 or 11 years old, and [DJJ] has not been aggressive in getting the services the child needs, or identifying the services he needs,” Gordon Weekes, who heads the Public Defender’s Office’s juvenile division, told the judge. “Once again, the department’s interests come first, and they are making sure” the agency isn’t accused of violating a judge’s order “rather than getting the child services.”

“I think this order needs to still be in place,” Weekes said. “It will act as a message to the department that everyone has worked very hard for this child.”

A DJJ assistant general counsel, Rhoda Nelson, vehemently denied her agency had intended to undermine Keishan’s chance at help. “It is not the department’s role or function or desire to interfere,” Nelson said. “And the department does not wish to face contempt charges merely for doing that which it is supposed to do.”

DJJ administrators were scheduled to meet at 3 p.m. Tuesday with other state agency heads to discuss ways to get the teen out of Broward’s lockup and into some kind of treatment center. But Orlando’s order could be interpreted as forbidding such a conversation, she said.

“We don’t want to violate your order, ever, your honor,” Nelson added.

Orlando instructed Nelson and Weekes to meet privately outside court and hash out an agreement that allows DJJ to talk about Keishan with other state agencies. He said such conversations clearly are in keeping with the “spirit” of the order as it stands.

Keishan has spent close to one-fifth of his life at the Apalachicola Forest Youth Camp, where therapists were charged with making him competent to stand trial. The facility has said, however, “that it has done all it can for him, and can’t get him to a place beyond where he is,” the judge said.

Finding a home and services for Keishan is the goal, and the order was designed to prevent anyone from thwarting that, Orlando said, adding: “We need everybody to work together.”

“This department can’t be above and beyond the most important issue here, which is what is in the best interest of the child,” Orlando said.

[This story was originally published by The Miami Herald.]