Displaced Asian Seniors Find Their Bearings With Help from Local Community Organizations

The story was co-published with AsAmNews as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

Korean-speaking seniors listened as Yeri Shon, associate director of Korean Community Center of the East Bay (KCCEB), provided in-language interpretation of why the fire happened and how residents could advocate for their well-being going forward.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

After being displaced by a fire in May in the Jones Senior Homes apartment complex in San Francisco’s Japantown neighborhood, elderly residents were abruptly forced to adapt to unfamiliar circumstances, cut off from their usual access to food, transportation, health care, and social networks. Chinese and Korean-speaking elders, particularly those who depended on temporary arrangements provided by Alton Corporation, the property management, were hit especially hard.

In reponse, The Asians Are Strong, a nonprofit, and Korean Community Center of the East Bay (KCCEB), as well as a group of on-the-ground volunteers came together to provide a range of culturally and linguistically tailored services. In doing so, they quickly closed gaps in direct services and created a model for rapid response that could be used in an emergency affecting underserved Asian seniors in the Bay Area.

Without medications, glasses or dentures

Research by AARP as well as the American Red Cross and American Academy of Nursing shows that older adults are at significantly higher risk for negative health impacts and casualties in the wake of natural and man-made disasters such as fires and floods.

Reasons for the added vulnerability include physical fragility, reduced mobility, limited access to transportation, lack of finances, insufficient digital communication skills, and absence of personal support networks.

Long before the Jones Senior Homes fire, resident Oh Kyeong, 82, was used to smelling smoke in her building and hearing alarms. Every three to four months during the 11 years she lived in the complex, someone invariably left a yam for too long in the microwave or a pot of jjigae soy-paste stew bubbling on the stove after leaving the unit.

But that one fateful Friday in May, Oh recalled, “Alarms went off – not the ones in the rooms but the really big, red ones in the corridor that are enough to shake the whole building.”

After three fire trucks arrived and black smoke began seeping in through her windows, she opened her door to look out into the hallway.

“The hallway was worse,” she said. “That’s when I decided I had to get out – I thought, wow, this is a big fire.”

She threw a sweater over her shoulders, grabbed her purse, and left without her eyeglasses or dentures. She also left her medicines behind.

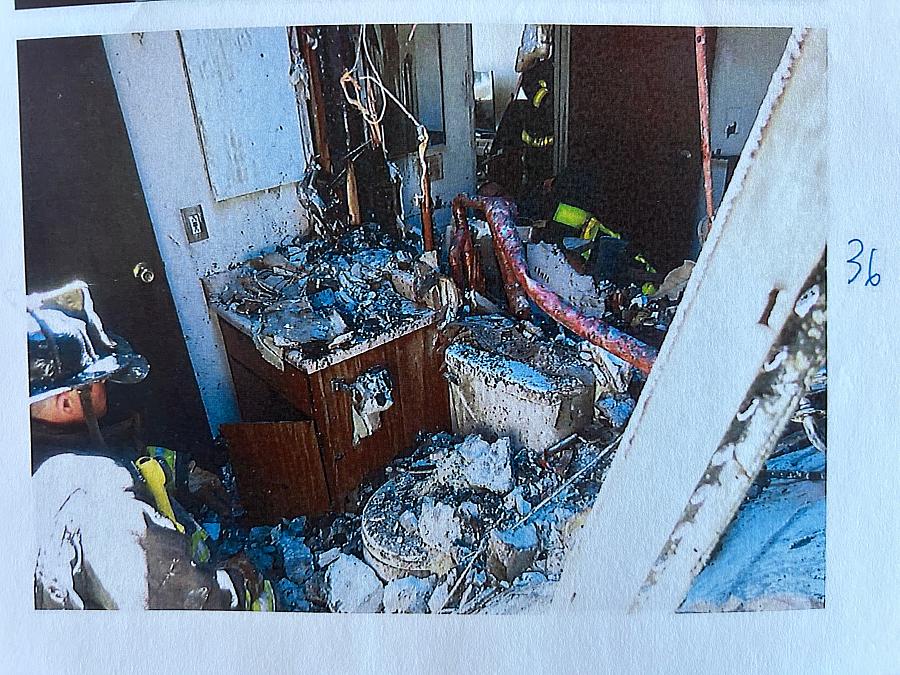

The fourth floor hallway of the Jones Senior Homes after the May 10 fire.

Courtesy SFFD

When first responders arrived, she told them: “Without medication, I will die tomorrow.” The American Red Cross provided her with a letter that enabled her to stock up on her life-saving medications at a Kaiser Permanente pharmacy nearby.

According to the fire investigation records from the San Francisco Fire Department, the Red Cross coordinated care for 102 seniors. Six residents sustained injuries, with two requiring hospital care.

A unit like Ms. Oh’s on the fourth floor of the Jones Senior Homes, after the fire.

Courtesy SFFD

Alton Corporation reported that 68 residents were living in 51-unit Building C before it caught on fire. The management relocated half of these residents, aged 71 to 104, to Extended Stay America in Alameda after their evacuation.

William “Billy” Hutton, director of Alton’s field operations, told AsAmNews in an email that the hotel was the only one in the Bay Area that agreed to accommodate the residents for such an indefinite period of time.

The hotel, located on an island south of Oakland, was far from home and walkable neighborhood resources.

“It’s unspeakable,” Oh said, waving her hand in exasperation when asked about transportation options. “You have to walk 20 minutes to try and catch a bus that comes once an hour.”

The remote location challenged the residents, several of whom used walkers or wheelchairs, and with limited English proficiency had trouble navigating new transit systems.

“We’re the ones who had no family to take us in or lived too far away,” said Oh, whose entire family remains in Korea, in her home city of Busan.

Displaced seniors struggle for resources

Zeien Cheung, one of the American Red Cross first responders and chair of the organization’s Bay Area-San Francisco leadership council, observed that the first popup local assistance center hosted by the emergency responders was poorly attended.

More people attended the second local assistance center, held at the same place, after Cheung incorporated in-language and transportation services.

When the initial emergency phase was over and the responsibilities of the Red Cross ceased, Cheung noticed that the seniors staying in Alameda still needed help.

After communicating with the residents directly and through interpreters, Cheung found that the seniors had little idea what resources were available to them.

Two of Alton’s service coordinators, responsible for assistance with social, health, education, transportation and wellness programs, occupied rooms in the Extended Stay hotel alongside the seniors. But they only spoke English, and numerous residents did not know the staff members were on site until months into their displacement.

Alton contracted with Meals on Wheels to provide food to the displaced residents, however, Cheung learned that the seniors were not consuming the Western foods that was delivered.

“We might think, oh my god, that’s so silly. At least you have food, why don’t you eat it? But if you think about it, it’s the first thing that can comfort them,” she said.

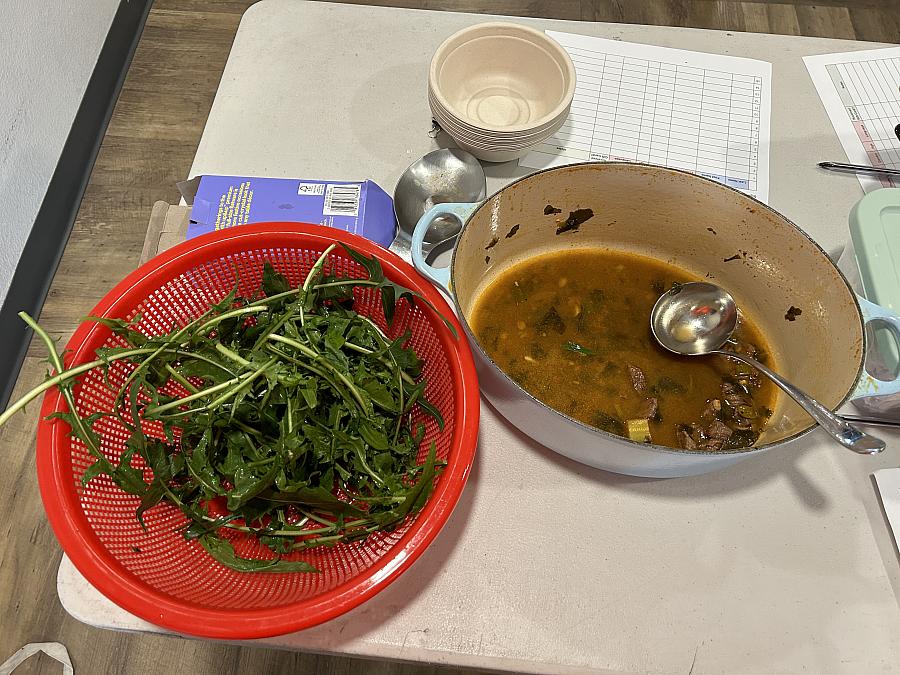

A fire-displaced resident of the Jones Senior Homes complex ate a bowl of hot Korean stew from a temporary seat provided by a water kettle box.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Fresh dandelion greens and doenjang jjigae soy-based stew made by a volunteer offers comfort to the seniors.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Additionally, while the hotel units featured kitchenettes and sinks, the displaced residents could not easily figure out how to get to the store to shop for ingredients or stock up on supplies to cook meals for themselves.

Cheung, who speaks English and Cantonese, and is the co-founder of the Asians Are Strong community safety and empowerment network, reached out to a pan-Asian network of multilingual volunteers.

One of her main contacts was through her friend Yeri Shon, associate director of the San Leandro-based Korean Community Center of the East Bay (KCCEB).

KCCEB, which serves Chinese and other Asian communities as well, began transporting the seniors to the grocery twice a week using a bus they had procured during the pandemic. On Thursdays, KCCEB and Asians Are Strong collaborated with the Moonstar Kitchen to provide culturally suitable, nutritious ready-to-eat meals for the seniors.

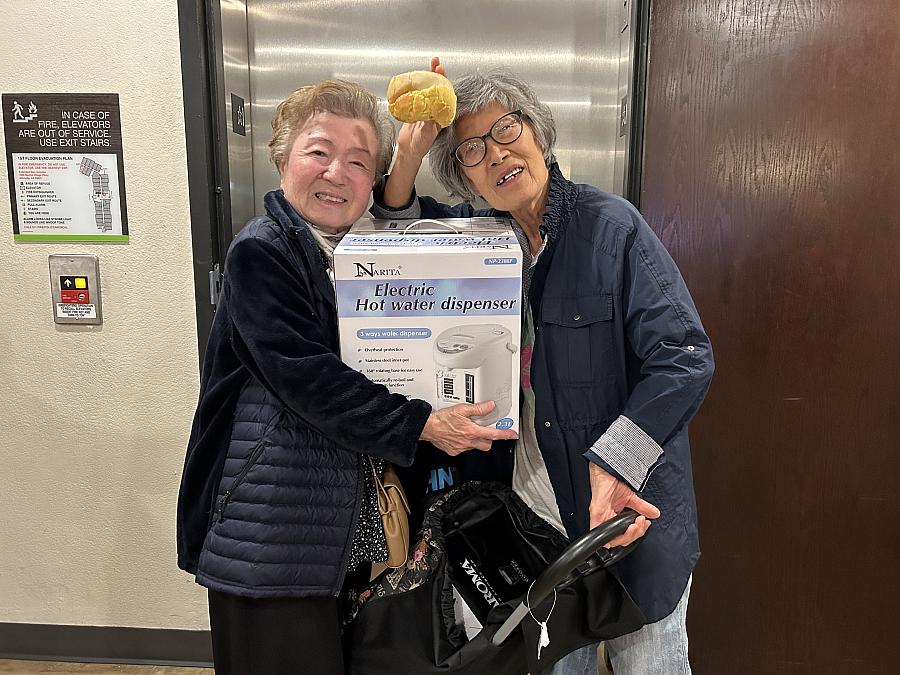

After conducting a social media campaign, the community responders further surprised the residents in early August with new water kettles and rice cookers, plus other in-kind donations from small businesses connected with local organizations like the Japantown Community Benefit District serving the three last Japantowns left in the U.S., and the Welcome Home Project assisting unhoused people in their transition out of homelessness.

82-year-old Jones Senior Homes evacuee Oh Kyeong, left, and the daughter of a 99-year-old resident, right, pose with in-kind donations from community workers.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Resuming health care and social services

Helping seniors resume their access to health care and social services, and advocating for their overall interests and continued well-being, has been a longer-term project.

“Even for those of us who speak English well, we were like ‘Oh my god, they never pick up our calls,’” Shon said, referring to the process of doing something straightforward, like calling the social security department to obtain replacement EBT cards for seniors already enrolled in CalFresh food benefits.

A week or two after the fire, select residents were allowed to reenter their units in San Francisco to retrieve essential possessions like documents and identification. But they only had 30 minutes to decide what they needed, and space in the vehicles going back to Alameda was limited.

Community workers from left to right: Moonstar Charitable Organization executive director Ariel Ng and development director Caleb Chen, Asians Are Strong co-founder Hudson Liao, KCCEB associate director Yeri Shon, Asians Are Strong co-founder and American Red Cross SF Leadership Council chair Zeien Cheung, and KCCEB program manager Art Choi.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Doctors’ visits became more accessible after a donation from Compassion in Oakland, an organization seeking to keep the Asian American and Pacific Islander community safe, funded door-to-door car rides through services such as Lyft.

The seniors, however, told AsAmNews that they have not taken advantage of these services. Some of them mentioned feeling guilty for taking benefits. Others said that walking was their least painful way of travel, while others said that they were just waiting to return home before going back to their doctors.

Long journey home

KCCEB's bilingual program manager Art Choi, left, listens to the experiences of Che Chun Hung, a displaced resident proficient in both Chinese and Korean, but not English.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

In a report, the Alton coordinators wrote, “We are amazed how some residents seem to embrace resilience and have a sense of hope while others had fallen into despair and hopelessness.”

They stressed that the chief need and desire of the displaced residents was to go back to their homes.

“It was crazy – it was a scramble,” KCCEB program manager Art Choi said, when recalling the first phase of the move back to AsAmNews. He described how the second floor residents being allowed back to their units had fewer than 48 hours of notice to pack up and clear the hotel premises. And the written announcement had been issued in English only.

On move-out day, the limousine Alton provided for transportation did not have enough space for everyone’s belongings. KCCEB staff and members of the Asians Are Strong network personally transported the residents who had no family or friends to help them with their possessions. Others tried to stow their things in the rooms of residents who had to stay behind in Alameda, leaving the quandary of how to retrieve the items later.

One resident never made it back – he died after being taken to a medical facility, leaving behind a wife with Alzheimer's disease. Alton Corporation stated in writing that the man had a pre-existing condition.

His neighbors said they only ever knew the lifelong Korean media journalist by the nickname daepyo, “our ambassador.” They shook their heads heavily with downcast eyes, depressed that his last months were lived in limbo, his last hours spent in chaos, and his last breaths drawn just shy of home.

After the Sept. 5 exodus of some Jones Senior Homes residents from their temporary living arrangements in Alameda, Alton Corporation began issuing translated communications in Korean (right) and Chinese (left) for those of the elders who are not proficient in English.

Photo by Jia Jung

“All these seniors were trying to use their walkers to put heavy boxes on to move stuff,” Choi said, recounting the physical burden and mental stress to the elders when no movers were present at the other end in San Francisco to help the elders settle back in or sort out items that they found had been removed, relocated, rearranged, or mixed with other residents’ property.

Concerned, Choi said that he encouraged residents to speak up more to their management about their needs going forward.

On Sept. 13, Alton Corporation’s Hutton distributed a letter of apology for the short notice for the move and promised to provide 5 to 10 days’ notice before the third and fourth-floor residents’ moving dates.

And after language access enforcement by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the management also began issuing communications in English, Chinese, and Korean.

The next move-in was supposed to happen on Sept. 30. At the time of writing, the third and fourth-floor residents remained in Alameda nearly a month after this date.

Somebody to call next time

Prior to the fire, many of the seniors did not know about the organizations that ended up helping them. They hardly knew one another.

Mr.Ko counts donations on a table of ready-to-eat meals, and tells KCCEB’s Art Choi about his intention to publicly thank the community organizations in the Korean language paper.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Ko Yong, 85 called Alameda 유배지 – yubaeji, a place of exile. But once volunteers began coming to Alameda to deliver necessities and advocate for medical care transportation, the lobby of the Extended Stay became abuzz with the opportunity to socialize and combat the negative mental health impacts of aging in a state of isolation, inactivity, and loneliness.

Recalling the days of his leadership in haninhoe Korean society organizations, Ko assigned himself as a kind of ringleader and spokesperson for the seniors, taking up collections of $10. When Shon and Choi asked why he was gathering the money, Ko replied that he wanted to pay for a thank you message in a Korean language newspaper to express the community’s gratitude to the organizations that worked behind the scenes to provide long-term rescue.

Weeks later, a group of ladies still waited to return to their homes. One woman shook her head at her peers’ complaints and said that things had been great and transportation had been easy. She expected everyone to go back to keeping to themselves once back in San Francisco.

Oh told her: “Your experience is different from mine.”

She said that she had felt depressed, lonely, and stuck in temporary housing. When Cheung invited her to an upcoming Asians Are Strong food event, Oh’s eyes sparkled.

KCCEB's associate director Yeri Shon, left, and Asians Are Strong co-founder Zeien Cheung, second from left, coordinate volunteers before distribution of essential goods and in-kind donations to the displaced seniors in Alameda.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

KCCEB and Asians Are Strong have recruited the Asian Law Caucus to support and oversee the rest of seniors’ transitions back home. Both organizations said that they will continue to be available to the seniors.

Cheung mentioned that the residents just need to remember they have someone to reach out to now if anything goes wrong.

In the meantime, she wants to enact the Red Cross’s recommendations for preventative mitigation of the disproportionately negative impact of disasters on seniors. She is thinking about how to integrate elements of the culturally attuned, comprehensive response to the Jones Senior Homes fire into post-disaster response protocols.

Volunteers at local community organizations that stepped in to help displaced SF Asian seniors manage their lives in temporary accommodations in Alameda.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

“If an earthquake happens right now, I’m not sure how many Asian communities know what to do, where to go,” Cheung said. “That’s the longer vision I have – combine the American Red Cross with a lot of other Asian communities so that you can provide in-language support and train other communities so that my community doesn’t miss out on certain things.”

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.