Echoes of Addiction: Women and Fentanyl

The story was co-published with Univision 14 Bay Area as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

Scores of women struggle with substance use disorder and mental illness in California. Fentanyl contributes to increased rates of drug overdoses and death.

Dayanna Monroy, Univision Bay Area

VO

In the Tenderloin district of San Francisco, it took very little walking for the cruel reality to hit us head-on. Too many women, even pregnant women, using drugs. One woman is lying on the ground.

DAYANNA: Can I help you?

VO

We covered her face because we don’t know her age, although she is clearly a teenager.

TEENAGER: No thanks…

VO

Sara says that she uses fentanyl as do many other women in San Francisco's Tenderloin district.

Dayanna Monroy, Univision Bay Area

She doesn’t want our help, so we decided to move on. When, suddenly, a woman with beautifully made-up eyes, walking with a slouched torso, and on high heels, approaches us. Her name is Sara, and she admits to using drugs.

DAYANNA: Do you use fentanyl?

SARA: Yes… but people see it worse than it is.

VO

She says that here in San Francisco's Tenderloin district many women trade sex for drugs.

SARA: And they have drug-addicted babies.

VO

At first, we don't see any Latina women, but when we walk a bit further we find them. When we try to approach, several men ask us to leave, but one of them agrees to speak with us. She was born in Honduras, is 23 years old, and has been living in the Tenderloin for five years. In other words, she arrived when she was 19 and has learned to protect herself.

MARIA: If someone looks for trouble with me, I have this ...

DAYANNA: Ah! And what is that???

MARIA: It’s a knife. If someone looks for trouble with me, they’ll always find it. I always have it.

DAYANNA: Have you had to use it?

MARIA: I haven’t had to use it yet, but if it happens, it happens.

VO

She assures us that she is clean and that she lives here because it is the only family she knows. But she tells us how others survive.

MARIA: There are women who sell their bodies for five dollars for crack. And they sell to many clients.

DAYANNA: Do they do it on the street?

MARIA: In a little house, yes. Like that. They live in one of those (points to a dirty tent) and it’s right in the middle of the street.

DAYANNA: Are there young girls too?

MARIA: Yes.

DAYANNA: What age?

MARIA: One that I know, she’s 16. She’s a smoker and also sells.

VO

Maria’s two children here live with their father.

MARIA: There are Latina women here who are pregnant too. They smoke. I met a pregnant woman who was six months along. But it was hard for her when she smoked, and when she didn’t smoke, it was even harder.

VO

Soon we encounter Dejanei crossing the street. She is seven months pregnant. She was born in Puerto Rico and lives close to the Bay Bridge.

DAYANNA: Do you use drugs?

DEJANEI: I’m not doing drugs now.

VO

Dejanei tells us she's been clean for two months, meaning she used drugs during the first five months of her pregnancy. This is her second child, and she wants to quit using drugs.

Dayanna Monroy, Univision 14 Bay Area

Dejanei tells us that she has been drug-free for two months, meaning she used drugs during the first five months of her pregnancy. This is her second child, and she wants to quit the addiction. Behind Dejanei, we see Najaney, also pregnant, but does not know how far along she is.

NAJANEY: Probably two weeks or less. I don’t know.

VO

Her belly looks more advanced. During the day she wanders without a fixed place, and when she can no longer walk around, she turns to this center.

DAYANNA: Do you use drugs?

NAJANEY: A little… yes, water ones… something made with water.

Nationally, this is a growing problem, and a significant portion of pregnant women who use drugs are using fentanyl, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

The number of deaths among pregnant women between the ages of 35 to 44 addicted to drugs has tripled in the United States from 2018 to 2021. The situation is so dire that the number of babies born with neonatal abstinence syndrome—babies born addicted to fentanyl—has also tripled.

According to the California Department of Public Health, "neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) is a drug withdrawal syndrome that most commonly occurs in newborns due to maternal use of opiates such as heroin, methadone and prescription pain medications."

What happens to babies born to women who use drugs? How are these children born? We asked

DENISSE NUNEZ / NEONATAL INTENSIVIST: It’s terrible to see those babies. Because, imagine, they are already accustomed to the drug and need it all the time. So, when you take those babies out of there, when they no longer have what they’ve lived with all their lives, they come out and have what we call withdrawal syndrome and start showing many symptoms: from being very irritable, nervous all the time, having problems sucking, eating, and sleeping.

VO

That is, babies are born addicted to fentanyl.

DENISSE NUNEZ / NEONATAL INTENSIVIST: What we have to do, unfortunately, is give them the drugs in a more controlled way. With a schedule, we switch them to methadone to gradually reduce and remove the addiction the baby has.

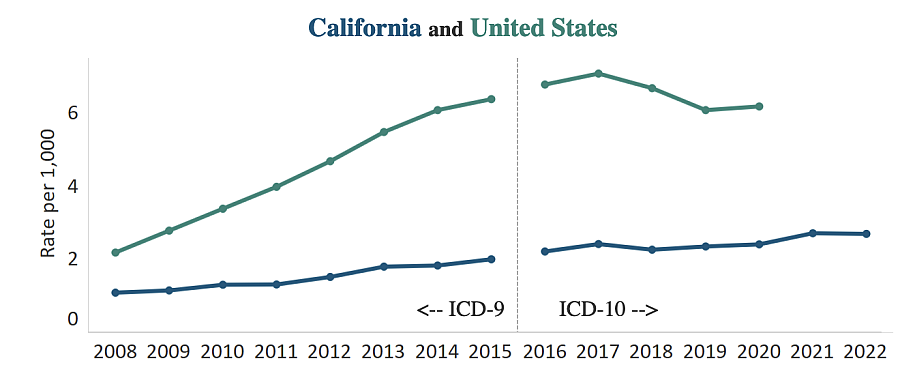

The rate (per thousand) of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome in the US and California.

CDPH

VO

While in the United States, the rate (per 1,000) of babies born with NAS has been reducing, in California it is climbing. In 2017, the national rate peaked at 7.1, lowering to 6.2 in 2020. In California, the rate in 2017 was 2.4 and has risen to 2.7 in 2022. In the last 10 years, from 2011 to 2022, the rate of babies with withdrawal syndrome has doubled in California, rising from 1.3 to 2.7 per 1,000 births.

SOT

DENISSE NUNEZ / NEONATAL INTENSIVIST: Even before we think the baby is overdosing on fentanyl, we are already giving Narcan.

VO

And in just four years, drug-related deaths among children also doubled, according to a publication in the Journal of Perinatal Medicine.

SOT

DAYANNA: Is this seen daily?

DENISSE NUNEZ / NEONATAL INTENSIVIST: Before, I could see an accidental ingestion once a month. Now, not a week goes by without seeing two or three cases.

DAYANNA: What happens to these children?

DENISSE NUNEZ / NEONATAL INTENSIVIST: Ugh. It depends on many things. It depends on whether the mothers are under child protective services. If they can complete the program, they can stay with their children; if not, there are consequences for that.

VO

Drug use in women usually stems from factors different from those in men… Men tend to use drugs for social reasons, while women use them to cope with emotional issues such as anxiety, depression, trauma, or abuse. In this circle that addicted women live in, becoming pregnant presents another painful moment, the imminent possibility of being separated from their children.

GABRIELA ESPINOZA / CASA AVIVA SPOKESPERSON: Normally in the area where they go to give birth, if the baby tests positive for substances, that’s usually when we get the call.

VO

For those living on the street, the alternative is to enter this transition house in San Francisco, part of the mayor’s Women’s Treatment Recovery Prevention Program, managed by Casa Aviva. Here, they can stay until their baby turns three months old.

GABRIELA ESPINOZA / CASA AVIVA SPOKESPERSON: Most of the mothers we receive are under the influence of fentanyl.

DAYANNA: Are there women who have gone through the program more than once?

GABRIELA ESPINOZA / CASA AVIVA SPOKESPERSON: Yes, yes. Unfortunately, yes. I’ve seen cases where it can be two or three times.

DAYANNA: How many of these women who come to you are Latina?

GABRIELA ESPINOZA / CASA AVIVA SPOKESPERSON: I would say 90% of our women are all Latina.

VO

And despite federally funded programs like the SAMHSA Mothers and Infants Recovery Program and the CDC’s Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome initiative, resources are lacking.

GABRIELA ESPINOZA / CASA AVIVA SPOKESPERSON: Yes, space is needed because in our program, we can accommodate between five to six women in the house, so for all the other women, there is no space, and they are on the streets.

DAYANNA: How could this cycle be broken? What more is needed for these women to start changing their lives?

GABRIELA ESPINOZA / CASA AVIVA SPOKESPERSON: A place to go after our program. Because after our program, it doesn’t mean they are cured, that they can leave and everything is fine, no, that really isn’t the case.

DAYANNA: And are there women who have had several of these pregnancies?

GABRIELA ESPINOZA / CASA AVIVA SPOKESPERSON: Yes, yes. Several. I normally see an estimate of four to seven pregnancies.

VO

According to research, women tend to become dependent on these substances more quickly, start using them with their partners, hide it better, and take longer to seek help due to gender roles. They are also abandoned more quickly by family, so they generally undergo rehabilitation alone… That’s why breaking the cycle is not easy and what is being done is not working, as fentanyl use among pregnant women is a growing issue in the U.S., leaving children who are born addicted and destined to live far from their mothers… who not only carry the stigma of drug addiction but also an even heavier stigma of being labeled as bad mothers.

This project is supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.