An Extra Layer of Care

The story was co-published with the World Journal as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

Chaplain Stephen Loi gives a talk to seniors on medical and caregiving topics.

Courtesy: Stephen Loi

When Peter Phung’s father introduces his son to friends, he doesn’t say “palliative care physician.”

He says “geriatrician.”

“People know what a doctor for old people is,” Phung said with a laugh. “But in our culture, palliative care isn’t even a word.”

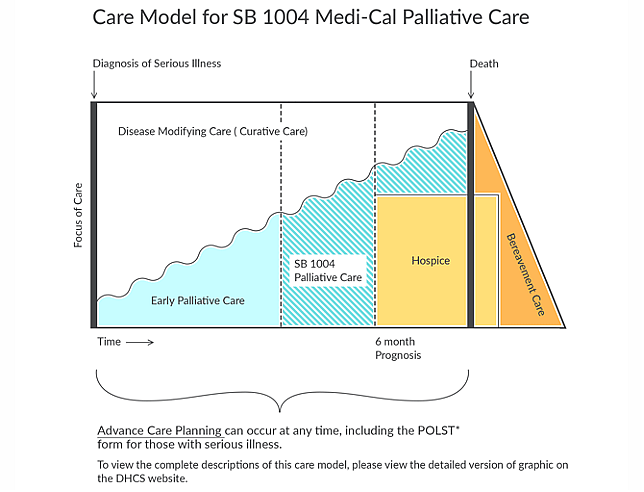

In the U.S., palliative care has expanded over the past two decades into a vital medical specialty — providing an “extra layer of support” for patients with serious illness and their families, often alongside active treatment. It focuses on easing pain, controlling symptoms, and helping patients navigate emotional and practical challenges at any stage of a life-limiting illness.

Yet for many in the Asian American community, the term remains unfamiliar. Talking about death is often considered unlucky; hinting at it can feel like inviting misfortune.

“When I started in the field 10 years ago, it wasn’t something you saw in clinics,” said Dr. Phung, director of palliative medicine and supportive care at Keck Medicine of USC. For years, he was the only Asian physician in the department. “We try to see patients as early as possible — but in Asian communities, the taboo around death makes it much harder.”

Beyond the Final Stage

Many people confuse palliative care with hospice care. Hospice, Phung explained, is for patients expected to live six months or less, with an emphasis on comfort in the final stage of life. Palliative care, by contrast, can begin as early as “day one of a difficult diagnosis,”and continue for years, encompassing hospice but also much more. It aims to improve quality of life, manage symptoms like pain, nausea, or anxiety, and support patients and families through uncertainty.

Phung emphasizes that it’s not about giving up. It’s about helping patients cope — and sometimes even thrive — through the journey, whatever the diagnosis. Patients often need more than medical procedures: they may need help communicating their wishes, navigating a complicated healthcare system, or simply having someone acknowledge their fears and uncertainty.

Dr. Phung, director of palliative medicine and supportive care at Keck Medicine of USC.

Courtesy Peter Phung

Unlike other medical specialties where doctors prescribe treatments directly, palliative care often begins with open-ended questions. This approach can feel unfamiliar for many families. “A lot of Asian patients really trust their doctors. They want you to just tell them what to do,” Phung said.

“But my field isn’t about giving instructions. It’s about understanding the wishes of the patient and the family. There is a lot of emotional investigation.”

A Cultural Wall of Silence

That journey often runs into a cultural wall. In many Asian families, talking about death is believed to invite bad luck or misfortune. Phung recalled his Vietnamese Chinese parents and his Chinese in-laws telling him, “By talking about death, you bring it closer.”

In Japan, Shinto beliefs emphasize purity, with death seen as ritually unclean. In South Korea, discussing death can feel disrespectful to elders. In Vietnam, ancestor worship and Buddhist traditions frame death as spiritual transition, yet open discussion is still considered inauspicious.

National data show that few Asian Americans have formally documented their end-of-life wishes — only about 7%, compared to 25% of white, 22% of Black, and 21% of Hispanic Americans.

Too often, conversations come too late. “Many patients end up in the ICU, intubated, sedated—and the family has no idea what the patient would have wanted,” Phung said. “The first question I ask is: what do you think he would have wanted? And they say, ‘I don’t know. We never talked about it.’”

For patients, illness itself often brings isolation, Phung noted, but in many Asian families, silence also comes from a fear of inviting bad luck by acknowledging death too soon or sparking gossip. “I grew up hearing, ‘Don’t tell anyone the family secrets,’” he said. “It would be dishonorable if people knew.” Some even hold superstitions about dying at home, believing the spirit would linger and bring guilt to the family. All of this makes open conversations about care even harder.

Delaying or avoiding conversations about end of life can leave families unprepared, especially when a crisis forces urgent decisions. Phung sees situations where the patient expresses a wish to spend their final days at home, while their children insist on hospital care, believing the patient will get better care.

A Family’s Journey with End-of-Life Care

For Felix Le, now in his 70s, caring for his parents would have been far more challenging without end-of-life care support. His mother passed away in 2022 at the age of 99 after receiving home-based hospice services during her final days. His father, now 103, continues to benefit from the same care.

“Nurses come every week to help with health check-ups and basic care like bathing,” Le said. “They also bring supplies — hospital bed, wheelchair, diapers, gloves, nutritional drinks, etc. It gives us so much peace of mind.”

Compared with primary care, Le said this type of support felt far more responsive. “It’s hard to take my parents to a family doctor, and they can’t provide such detailed and consistent services anyway,” he explained. “Family doctors have too many patients and not enough time.”

But language barriers remained. “Most of the nurses spoke Spanish,” Le noted. “My parents didn’t feel comfortable with them doing intimate things like bathing because they couldn’t talk to them.”

A 2020 national survey found that compared to white patients, racial and ethnic minorities are not only less likely to enroll in hospice but, if they do, are more prone to receiving substandard care. Training hospice staff in cultural competence (CC) — including cross-cultural communication, awareness of death-related beliefs, and spirituality — has emerged as a promising strategy to reduce these disparities

Le avoids using the Chinese expression “臨終關懷” when talking about end-of-life care. “It sounds like you’re sending someone off to die,” he explained. “Juts using the English word ‘hospice’ works better.”

For Le and his wife, their own wishes are clear: no aggressive treatments, no emergency-room heroics. “Life isn’t about length; it’s about quality,” he said. “We don’t want unnecessary suffering.”

But Le hasn’t shared many details with his American-born children. “They grew up here; our views are different,” he said. “They wouldn’t understand how we think. The best thing we can do is make our own plans so we don’t burden them later.”

The Volunteer’s View

In many Asian cultures, family members — often adult children — are expected to make the final medical decisions for their parents. Those decisions can sometimes leave deep scars.

“Some family members never speak again,” said Sandy Chen Stokes, founder of the Chinese American Coalition for Compassionate Care. “Some children carry guilt for life over those final medical decisions.”

Chinese American Coalition for Compassionate Care(CACCC)and UC San Francisco co-hosted a workshop to help the Chinese community address caregiving challenges in Sacramento in 2024. CACCC founder Sandy Chen Stokes (far right).

Courtesy Sandy Chen Stokes

With decades of experience, Chen has seen how early conversations can change the course of a patient’s care and spare families years of regret. Her organization provides workshops, bedside support, and resources in Mandarin and Cantonese to help families understand their options before a crisis hits.

She calls early planning “a best gift to yourself and the people you love.”

Both Chen and Dr. Phung noted that medical decisions in many Asian families are made communally, even when they conflict with the patient’s wishes.

“There is a concept in Chinese culture called shànzhōng — a good death,” Chen explained. “Many people hope to pass away at home. But if you spend your final days in the ICU, that wish becomes almost impossible.”

Without palliative care support, the burden on caregivers can be overwhelming. Chen has seen families pushed to the brink. Caring for a critically ill family member can lead to exhaustion, depression, and anxiety—mental health struggles that in turn affect physical health. “Some caregivers die before the patient.”

Chen observed that many Chinese families regard the end of life with fear and helplessness, largely due to lack of information and resources. Even American-born, fluent-in-English adult children often had never heard of palliative or hospice care until a crisis forced them to learn.

“Once you have these services, you’re no longer fighting alone. There’s someone to walk that last part of the road with you,” Chen said.

Breaking the Silence Around Death

Stephen Loi, a Malaysian Chinese chaplain fluent in Mandarin, Cantonese, and English, has spent more than a decade supporting Asian immigrant families in Southern California. Now working independently, he visits hospitals, nursing homes, and homes to offer support and guidance on end-of-life decisions.

Loi admitted he was surprised by this interview request. “No one has ever come to me wanting to report on this topic,” he said. “It’s considered too sensitive, too uncomfortable.”

Loi recalls families who asked the care team not to even mention words related to death or hospice in front of the patient, fearing it would cause distress. “I’m often told by the families not to say it in front of the patient,” he said.

This mirrors findings from studies on Asian American families, where relatives frequently shielded patients from any mention of death, hoping to protect them but often leaving everyone less prepared for the inevitable.

Loi used to focus solely on providing spiritual support only, but now he describes his role as being more like “customer service”— answering calls, providing education, listening to families’ needs, helping them solve problems, and offering language assistance. “In many facilities and hospitals, I’m the only person who speaks Chinese,” he said.

Language, he added, is more than convenience — it can be a source of emotional support. “For many immigrants, language itself is a kind of spiritual comfort. When patients hear someone speaking their language, it makes them feel safe.” Each week, Loi brings a Chinese-language newspaper to patients and chats with them in their mother tongue.

But illness often erodes a patient’s ability to speak a second language. “They may no longer be able to communicate their wishes in English,” Loi explained. “And if their children aren’t fluent in Chinese, that creates another layer of difficulty.” Misunderstandings, he added, can compound stress at the very moment when families need clarity the most.

“Death will come, whether we talk about it or not,” Loi said.

Dr. Phung has seen how this silence leaves a heavy legacy. “I’ve had younger patients lose parents and tell me they had no idea what their parents were thinking in their final days — whether they were scared, whether they were in pain.”

“Legacy planning isn’t about being ready to die. It’s also about leaving guidance, memories, and comfort for the people you love — like writing a letter to your kids when they leave for college. You may not be there in person, but your love and support remain,” Dr. Phung said.

A System with Gaps

Even when families are open to palliative and hospice care, access can be another hurdle. In smaller Asian American communities, specialized programs are rare.

“It’s a money-losing kind of activity,” Phung said. “We spend an hour with each patient, talking about how they’re feeling and what matters to them. We don’t do procedures.” Without financial incentives, smaller hospitals and clinics often leave palliative care to large health systems or nonprofits willing to absorb the cost.

In the growing Chinese communities of the Inland Empire, for example, few organizations provide such care — let alone culturally tailored services. Providers like Loi often drive long distances to reach these patients.

Recruiting is another challenge. Although there are many Chinese doctors, nurses, aides, etc., few want to enter what they see as a “taboo” field. Over the years, Loi has invited many nurses to join. “But the answer is always no,” he said. “Some people find the work too depressing; others think it’s exhausting because you’re constantly running around.

A 2022 study in the journal BMC Palliative Care found that even in professional settings, Chinese nurses reported anxiety and fear when discussing death, reflecting how deeply cultural discomfort can shape professional attitudes.

But for Phung, Chen, and Loi, one belief guides their work: palliative care is not about dying—it’s about living well, all the way to the end.

Toward a More Inclusive Future

Despite the barriers, there are signs of progress. Community organizations like Chinese American Coalition for Compassionate Care now offer bilingual workshops to raise awareness, and some hospice agencies in Los Angeles — such as Asian Network Pacific Home Care & Hospice and Heart of Hope Asian American Hospice Care — provide culturally sensitive services with Mandarin-speaking staff.

On the policy front, California’s Senate Bill 1004 requires Medi-Cal managed care plans to offer palliative care, and Medicare covers both palliative and hospice services for eligible patients. Hospice care serves those with a prognosis of six months or less, focusing on comfort rather than cure, while palliative care supports anyone with a serious illness and can be provided alongside ongoing treatments.