In the Face of Abuse, She Chose Survival — and Now Helps Others Do the Same

The story was originally published by the KQED with support from our 2025 California Health Equity Fellowship.

Survivors of domestic violence often face silence, stigma and complex cultural pressures, yet advocacy and support networks are helping break the cycle of abuse.

(Illustration by Anna Vignet/KQED)

Jagbir Kang was soundly asleep next to her 4-month-old son when she was jolted awake by violent banging on her bedroom door in Fremont. She scooped her baby into her arms just as her husband forced his way in.

Earlier that night, Kang had called the police to report a family disturbance — her husband had hit her. When officers arrived, they asked whether she wanted to press charges. Kang said no. They asked her if she needed a place to stay for the night, away from her husband. Again, she said no.

Kang, who was 28 and had been married for two years, said she had no intention of leaving. All she wanted was for the abuse to stop.

Domestic violence often goes unspoken in Asian communities, where stigma, family dynamics, immigration status and lack of culturally responsive services can make it especially difficult to seek help. Survivors like Kang say those layered pressures — along with the fear of losing family, support systems or legal status — kept them silent for years.

But a growing network of advocates and organizations are working to break through that silence and build support systems that meet survivors where they are.

Kang remembers her husband taking a fistful of her hair and slamming her head repeatedly against the wall. Bruises blossomed across her face, and the trauma caused temporary blindness in her left eye. Even as she screamed that she couldn’t see, he kept hitting her. When he wrapped his hands around her throat, Kang feared he wouldn’t stop until she was dead.

Jagbir Kang at her home in Fremont on July 25, 2025.

(Martin do Nascimento/KQED)

“It seemed like it was never-ending,” she said.

Kang, now 46, met her husband through an arranged introduction by her parents in March 2006. They married a few months later. The emotional and verbal abuse began almost immediately, Kang told KQED. By the time their son was born, it had escalated to physical violence. Kang said her husband never hurt their children, but they witnessed the verbal and emotional abuse.

She stayed with him for 13 years.

The day after the 2008 assault, when she spoke with doctors, she said she’d fallen on a hike. When her friends asked if she was OK, she reassured them that she was fine. She held onto hope that things would change — even when, deep down, she knew they would not.

It wasn’t until she was diagnosed with cancer that she decided to leave.

“I’m a very optimistic person, and I felt that he would change now that I’m diagnosed with an illness,” she said. “Actually, the abuse became worse after that, and I decided I couldn’t do it anymore … I worried about money and losing children, but then I was like, it’s OK.

“It’s still better, because I’ll be alive for my children. Otherwise, I’d be dead.”

For some Asian survivors, the decision to leave an abusive spouse or family member is fraught with fear — of community rejection, of losing immigration status or of being unable to access culturally competent services.

According to the Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence, up to 55% of Asian women reported experiencing some form of intimate violence in their lifetimes. The rates vary across ethnic groups — Vietnamese, Indian, Chinese, Korean and others — but experts agree that underreporting is common and the true numbers are likely higher.

Mallika Kaur, director of the Domestic Violence & Gender-Based Violence Practicum at Berkeley Law, said that cultural expectations play a major role in keeping survivors silent.

Traditional gender norms can make it difficult for communities and families to engage in conversations about gender violence. If a woman has been repeatedly taught to follow her husband, she may feel uncertain about what will happen if she chooses to leave, Kaur said, adding that the fear and uncertainty caused by patriarchal standards is something survivors experience outside of Asian communities as well.

Kaur, who is also executive director of the Sikh Family Center, an organization focused on addressing gender-based violence nationwide, said survivors also fear backlash from their communities. For people whose entire support system is grounded in a tight-knit cultural or religious community, the risk of alienation is high.

“[Survivors] may not see a way of detangling themselves from their abusive partner without losing all sense of community,” Kaur said. “It can determine whether or not they’re going to speak about the abuse, seek separation or even distance themselves from the abusive party.”

After she left her husband, Kang said she felt shunned by people she once considered friends and family. In many South Asian communities, divorce carries a heavy stigma — not just for the individual, but for the entire family.

Jagbir Kang washes the dishes at her home in Fremont on July 25, 2025.

(Martin do Nascimento/KQED)

“People didn’t want me around,” Kang said. “They didn’t know what I was going through. I didn’t know what the cycle of abuse is. When I learned that this is the abuse cycle and that it’s going to repeat … I would tell my people. Nobody would listen. They don’t believe you.”

Abuse in Asian families isn’t always limited to partners.

According to a study by the Pew Research Center, 29% of Asian Americans lived in multigenerational households in 2016 — more so than any other ethnic group. Kaur said that in a country that emphasizes individualism, the dynamics of collectivist family structures are often misunderstood.

“We need to think beyond partner violence in these communities. In-law violence is something people at times cannot fully wrap their heads around,” she said. “Even if they don’t live in the same home, the family structure can often be so that these hooks and their say about what should or shouldn’t happen carries a lot of weight and determines somebody’s full lived reality in a marriage.”

Soon after Kang married, her in-laws moved in. She described her father-in-law as narcissistic and dangerous. Their presence, she said, made the abuse worse, and it only escalated after her mother-in-law died.

In some families, elders and community members can step in and provide support to survivors. In others, the presence of more relatives simply adds to the trauma.

Immigration status and financial instability also pose significant challenges. Shailaja Dixit, executive director of Narika, a Bay Area nonprofit that serves South Asian survivors, said many immigrant survivors are vulnerable because they rely on their abusers to manage documents or visas.

In other cases, a woman’s finances are controlled entirely by their husband. Some are forbidden to work. Others may work but not have access to their own wages, Dixit said. If the survivor chooses to leave, they risk falling into poverty or being left without any income.

“Not everybody is in a position to leave,” Dixit said.

When culture meets care

Saara Ahmed, a spokesperson for the Asian Women’s Shelter in San Francisco, said more needs to be done to create accessible, culturally responsive support systems for Asian survivors.

Each community and individual has different needs and traditional service providers are not always equipped to provide care in a survivor’s native language or to understand their cultural context, Ahmed said.

“It can be really difficult [for survivors] to access things like shelter and support and services when there is, in addition to the kind of existing taboos and stigmas that domestic violence survivors face, those added barriers of cultural understanding and language needs,” she said.

Jagbir Kang at her home in Fremont on July 25, 2025.

(Martin do Nascimento/KQED)

The Asian Women’s Shelter was created in direct response to the gap in critical services for survivors, she said. In addition to providing clients with emergency housing, legal assistance, trauma counseling and financial assistance, the organization provides thousands of hours of language-specific case management each year.

Services are available in over 40 different languages, including Cantonese, Korean, Arabic, Indonesian, Khmer, Punjabi and Tagalog. The shelter also runs two outreach programs focused on Arab and Korean survivors who have experienced domestic violence or human trafficking.

Ahmed said the nonprofit is also engaged in outreach efforts to spread awareness about domestic abuse and other forms of gender-based violence through community events and partnerships. There are a lot of misunderstandings when it comes to domestic violence, she said, and part of the solution is teaching people about the different forms abuse can take and what the long-term repercussions are.

The shelter is part of the San Francisco Domestic Violence Consortium, a network of local service agencies.

“It’s important to have flexible models that make room for the uniqueness and individual needs of survivors,” she said. “Survivors face a lot of stigma, victim blaming and kind of overall societal and cultural misunderstandings and misrepresentations.”

Narika offers wraparound services as well, including shelter, transportation, financial counseling and legal aid, Dixit said. The organization also provides support groups Monday through Friday, giving survivors the opportunity to find community with others who have similar experiences. Dixit said Narika served more than 900 survivors last year and 500 since January.

She emphasized that even within South Asian communities, experiences vary widely. Within the South Asian diaspora, there are dozens of microcultures and ethnic groups, Dixit said. While domestic violence occurs in every community, each one experiences it differently and has a different understanding of what it looks like.

“I feel like one of the biggest things an organization can do is be hyper local, settle into the community and be willing to listen and spend time with survivors and community,” she said.

Kaur said it’s important to recognize the role that a person’s community can play in finding culturally sensitive solutions to combat abuse. She noted that the “cultural dog whistle” — the idea that certain forms of violence occur only in select communities and stem from their cultural beliefs and practices — can be counterproductive.

It overlooks the possibility that community members themselves may be the best defense against violence, especially when external entities such as law enforcement can also perpetuate harm, she said.

“It can sometimes be a first preference for survivors,” Kaur said. “Many survivors will talk about approaching somebody in the community, whether that be elders, in-laws, a mutual relative … How those people react can be really essential to the survivor’s sense of what’s happening to them.”

Reclaiming life, rewriting legacy

Kang’s healing has been long, but she now describes it as empowering. She turned to meditation, yoga and other forms of self-healing. She confided in close friends and family. She leaned into their love.

“I did a lot of things to recover. I basically held onto anything that I could at the time,” Kang shared, her voice filled with mirth. “It’s like pulling. You’re drowning, and you want to not drown.”

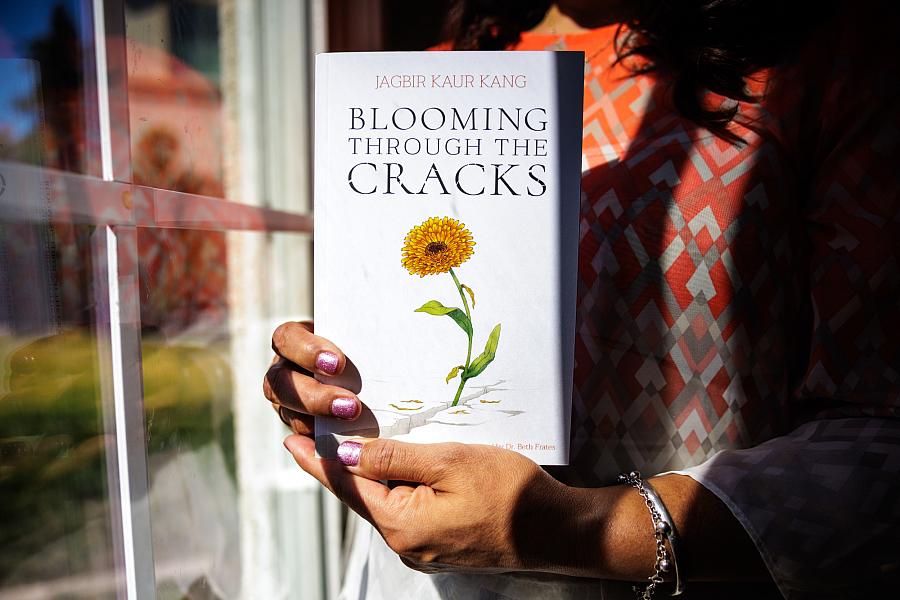

When she looks at her two sons, Kang said she is filled with pride at how far she’s come on her journey. Part of her growth was learning that violence is intergenerational, she added. Leaving her husband, she said, was the first step in breaking the cycle of intergenerational violence. She is alive because of her decision to separate herself from the abuse and choose healing, a process she documented in her book on post-traumatic growth titled, Blooming Through the Cracks.

Jagbir Kang holds her book at her home in Fremont on July 25, 2025.

(Martin do Nascimento/KQED)

Kang said she was fortunate to have a strong support system at the time of her divorce. She also had U.S. citizenship, a good job and a home she owned. She acknowledged that not all survivors are in the same position.

After Kang’s separation, she received master’s degrees in psychology and counseling, respectively, from Harvard Extension School and Palo Alto University. In addition to her full-time role as a senior director of product management at tech company Cloudera, Kang also works as a therapist at a psychiatric hospital where she helps other survivors of domestic violence.

“I tell [survivors], ‘Your challenges are different from mine. My challenges were different from yours,’” she said. “If you’re a survivor, I cannot tell you that the same thing will happen to you as it happened to me … If you decide to stay, you can stay. We will do safety planning.”

“I will never stop advocating,” Kang continued. “I will never stop talking about this.”