Family First

This project was led by Catherine Stifter, a 2013 California Fellow, who takes an up-close look at the high rates of high school dropouts through the lives of four young people from the Central Valley.

Other stories include:

Roosevelt Webb (right) plays video games with his nephew.

Andrew Nixon/Capital Public Radio

Roosevelt Webb Jr., had no choice but to drop out of Edison High School in Stockton – his mother was sick and his father was dying.

And for Roosevelt, family comes first.

“Spending time with my dad was more important than spending time in school,” says Roosevelt – a slightly-built, affable 22-year-old.

“It was kind of my responsibility to help take care of him…it felt like a fulltime job.”

Roosevelt was one of 1,369 African American students who dropped out of the Stockton Unified School District during the 2008-09 school year. Stockton Unified had an 18% dropout rate that year and one-out-of-four students who left was African American.

Roosevelt dropped out during the final half of his senior year. But even if he had stayed, graduating with his classmates would have been uncertain. “Most of my grades were far below basic,” says Roosevelt. “They were mostly Ds and Fs, except in my math class.”

Roosevelt credits his Algebra teacher for the good marks he received in her class. “She was always one-on-one with the kids.” That’s something Roosevelt says was missing from his other classes at Edison High.

“When I first started going to Edison, I was thinking like ‘oh man, this is my time to shine.’ But it’s a big eye-opener because (there are) just so many kids there that it’s hard to get recognized and get noticed…your talents are unseen. Being at a school that big makes it very hard for anyone.”

“Some kids drop out of our large schools because they are just too big… It’s scary for some kids.” – Dee Alimbini, Stockton Unified School District

Read more about SUSD efforts to reduce the dropout rate.

Two years after Roosevelt dropped out of high school his father died of complications from diabetes and congestive heart failure. His father was 52. Now Roosevelt helps his mother who suffers from Crohn’s Disease, which is an inflammatory bowel illness. She’s 54.

But, caring for his mother is not the around-the-clock responsibility it had been with his father.

So Roosevelt had time to go back at school and stands now on the threshold of accomplishing a family first – receiving a high school diploma. He’s enrolled in an unconventional dropout recovery program intended to give low-income young adults, even those with troubled pasts, a second chance.

Barring another family crisis, Roosevelt will get his high school diploma in 2014.

“The only thing that could mess me up,” says Roosevelt “is if something was to happen to my mom. But I don’t think there’s anything that can hold me back at this point, I’ve been through so much already.”

SECOND CHANCES

“They messed up in school. They didn’t take things seriously. (Building Futures Academy) is their second chance.” – Sheilah Goulart, Director

Roosevelt attends Building Futures Academy (BFA), a charter high school in Stockton; part of the San Joaquin County Office of Education’s “YouthBuild” program. BFA combines academic classes with hands-on construction training for dropouts between the ages of 17 and 24. Students are paid stipends to cover basic living expenses; $8.00 an hour for about 60 hours per month.

“It’s their second chance,” says BFA and YouthBuild Director Sheilah Goulart. “They messed up at school. They didn’t take things seriously and they needed a hands-on environment—

that’s what we offer here. What’s special about BFA and the charter schools of its nature is that we offer the small class sizes; we’re more of a family. When the students come to our school they feel like they’re a part of something.”

Sheilah Goulart, Director of San Joaquin Building Futures Academy on the first day of the 2013-2014 school year. Andrew Nixon/Capital Public Radio

In Roosevelt’s case, a fading interest in school was further undermined by a family crisis.

“He was kind of lost, says Goulart. “His father (died) just before coming here. He was looking for that father figure. I know that’s probably why he connected really well with many of the male (teachers) here.”

Teachers like Lucas Homdus – an English instructor at BFA for five years.

Homdus says Roosevelt isn’t a typical BFA student. “He looks you right in the eye, shakes your hand and he just strikes you as a good guy. You think, ‘oh man, what’s this guy’s angle?’ And then you realize, ‘oh, that’s really Roosevelt.’”

Most of the school’s 150 students, says Homdus, come from rough backgrounds.

“They’ve made money all their lives, but they’ve never actually worked an honest job. So they know what it means to have work ethic out on the street but they don’t necessarily know what it means to have a boss in charge of you.”

The YouthBuild model combines vocational training with academic courses. That gives faculty more time to teach students the real-world skills needed to apply for jobs. “You have to teach them the difference between the language they use on the street versus the language they’re going to use for a job interview,” says Homdus.

More than 270 YouthBuild programs are operating throughout the country, including about 30 in California.

All YouthBuild students come from poor families. That’s one of the eligibility requirements set by the U.S. Department of Labor, which helps fund the program.

“Most of them are well below the poverty level,” says Goulart. “I would say that our ethnicity is Hispanic, African-American, Caucasian and Asian, probably in that order. And many of our young people are also parents.”

Goulart says many also have troubled pasts. But she says those students tend to abandon the “thug life” attitude once they step on campus. “We probably work with almost all the gangs that reside in Stockton. In seven years that we’ve been in existence, we’ve (only) had two fights. So the young folks know that this is kind of neutral territory.”

“We’re pretty tough people,” says Goulart of the staff and faculty at BFA. “But you don’t really have to be tough. You have to be compassionate.”

The school year begins with a two-week orientation designed to develop “mental toughness.” Students are divided into squads. They do a lot of marching and team building exercises. They share their stories, revealing why they weren’t successful in high school.

Andrew Nixon/Capital Public Radio

It may seem like a boot camp to outsiders, but Goulart calls it a root camp “because we’re trying to get down to the root of the issues that are keeping these young folks from being successful and get them to start thinking about what they need to do to transform their lives.”

Transforming lives is not cheap. With all the services provided, including mental health and career development, the program costs about $15,000 per student per year. Goulart says that’s a lot less expensive the $50,000 a year it costs to incarcerate a prison inmate.

“The one thing you have to think about when you’re investing in a young person that’s trying to change their life is that you’re taking them out of the prison system. You’re also taking them off of welfare rolls. They’re starting to contribute to the tax base. What we’re doing is providing them an opportunity.”

That opportunity includes teaching students carpentry, masonry and other trades. Darren Branch is one of BFA’s construction instructors. He has taught Roosevelt how to hang sheetrock.

“Some of these kids, when they come to us, they’re feeling pretty hopeless about life,” says Branch. “But some of them see the opportunities here. Roosevelt wants a better life and he has a very good idea of what it takes to get that.”

A BETTER LIFE

A typical day at home for Roosevelt consists of “enjoying the family and having a little bit of fun.” And for Roosevelt, fun means video games.

Roosevelt lives with his mother, two younger nieces and a young nephew. Other family members often drop by to play video games too, including Roosevelt’s older brother Ydale and Ydale’s young son.

Roosevelt and his family enjoy video games in the family home. Andrew Nixon/Capital Public Radio

“Super Smash Brothers Brawl” is the game Roosevelt favors when his nieces and nephews are playing. “The Nintendo all-star characters get together and challenge one another,” explains Roosevelt about the game’s objective. “It’s not too violent so the kids can play as well. You don’t have to worry about any blood and guts flying everywhere.”

Roosevelt and his family rent a two-story, three bedroom tract house in South Stockton. It was built in 2006.

The formerly foreclosed home is near Charter Way – a busy thoroughfare with houses on one side and commercial industrial buildings on the other side. Several vacant lots pepper the neighborhood; empty lots where developers might have built homes before the housing bubble burst.

The family survives on Roosevelt’s stipend as well as welfare, food stamps and disability payments.

Roosevelt says his dream is to become a video game designer.

“What I want for myself in the future – real simple: a nice car, a good paying career and my own house,” says Roosevelt. “Ever since I was younger, I always played video games just like any other kid. But (creating) video games (storylines)…you have a chance to affect someone’s life in a positive way. It can actually change the way they think and the way they do things.”

After he gets a high school diploma, Roosevelt says he wants to enroll in computer science classes at San Joaquin Delta College – a community college in Stockton.

But if a career in computers doesn’t work out…“then I figure I would just do what I learned from YouthBuild and I would be in construction.”

YouthBuild is a “direct entry” program for two construction unions and students have the opportunity to apprentice in the construction industry.

In his first year at BFA during the 2012-13 term, Roosevelt learned construction skills, including drywall installation, house painting, sod laying, and spraying foam insulation in attics. He worked on Habitat for Humanity homes in a neighborhood near Stockton Airport, and at retail office space in Downtown Stockton.

Roosevelt and the other BFA students are treated as if they’re already apprenticing on a construction site.

“If you show up late on jobs or you’re horsing around, you’re not going to last,” says Branch. “So the accountability that we get to hold these kids to is really valuable.”

Before BFA, Roosevelt says he had no experience with construction or with tools for that matter.

“I’ll be the first in my family to get my high school diploma. I know my dad would be proud.” – Roosevelt Webb

Roosevelt Webb lays sod at a Habitat for Humanity project in Stockton. Andrew Nixon/Capital Public Radio

“My dad was always trying to get me to use a skill saw and I’d never want to use it,” says Roosevelt whose father was an independent auto mechanic, fixing people’s cars in the family’s garage. “And now I can just pick one up and make the cut. You go from being a kid to actually moving on with your life and doing something about it.”

“I’ll probably be the first one in my family that never smoked weed or never drank and the first to get my high school diploma,” says Roosevelt. “If my dad was here now I know he’d be proud.”

REVERSING A FAMILY TREND

Nobody in Roosevelt’s immediate family has a high school diploma. His mother, father and two older siblings all dropped out.

“It’s a lot harder for kids if their parents don’t finish high school,” observes Roosevelt. “If their parents made bad decisions, then most likely the kids are going to make bad decisions.”

Despite some less than stellar grades at Edison High, Roosevelt was on track to buck the family trend of dropping out. That is until his father’s condition worsened, forcing Roosevelt to leave Edison High to take care of the family.

“I didn’t like it,” says Bobbie Jean Webb, Roosevelt’s mother, about her son dropping out of high school. “Because I thought that he could graduate and really become somebody.”

But Bobbie Jean says she couldn’t take care of her husband who, in addition to congestive heart failure and severe diabetes, also required frequent hospital visits to remove cysts.

“I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease and that made my immune system weak,” says Bobbie Jean. “And by (my husband) having open sores, his doctor recommended I not be around him. So Roosevelt had to take on that job…” of cleaning and bandaging his father’s wounds.

Roosevelt became the man of the house after his father died; running errands and helping to pay the rent with his BFA stipend.

“I barely leave the house,” says Bobbie Jean. “I get anxious. Roosevelt does all the running for me. I send him to the grocery store; I send him to the bank. I made him my payee.”

“I’m very proud of him for going to school. I want to see my son up there with his diploma. I’d be telling everybody my boy goes to school and he’s working to help pay the bills. I’m very proud of him.”

Bobbie Jean’s older son, 28-year old Ydale Webb, wants to see his younger brother Roosevelt earn a diploma too.

“That’ll be a good thing for just the family period,” says Ydale who also dropped out of Edison High and is unemployed. “Just to have somebody to say ‘you graduated – now you can go on and do what you want to do, have the life that you want to have, more jobs and all that…it’ll be easier for him.”

Ydale lives with his girlfriend and young son in a neighborhood near the Stockton Airport. “Out there, it’s real tough because people (live) off of welfare, it’s kind of hard,” says Ydale. “Me not finishing school, it impacted my life greatly by the simple fact that most of the times when I go apply for a job, they ask me for a high school diploma or GED and I don’t have it.”

Ydale says he hasn’t worked for six months. The last job he had was on a production line for a fruit packing company.

Roosevelt and his brother, Ydale, run an errand in Stockton. Andrew Nixon/Capital Public Radio

“It was during the cherry season. It only lasted so long and then once they let you go you’ve got to wait until the next year comes around to do it again. But if you have a high school diploma, most (companies) are willing to keep you because they know you have the education to continue and to go on further in the company instead of just being in that one position.”

Ydale says he and an older sister dropped out of high school for the same reason: “school just got boring to us. It’s like ‘I don’t need no more of this.’ We just walked away from it. I started going towards the streets with my friends, doing what they were doing.”

STOCKTON’S CRAZY

“Going towards the streets” has a familiar ring for Roosevelt’s BFA English teacher Lucas Homdus. “When you’re not in school, there are a lot of other things you can get into: getting arrested, drug issues, finding people to have trouble with.”

Homdus says smaller class sizes and early intervention programs could go a long way toward preventing dropouts. “Once you’re behind in school for these guys there’s no catching back up.”

“The majority of our students don’t have (parents) pushing for them. They don’t have that expectation of finishing high school. So when you don’t have anybody expecting that of you, why would you expect that of yourself?”

About 20% of the students at BFA don’t complete the program.

“As good as we are, sometimes students fall through the cracks every year,” says Homdus. “They only show up once or twice. You can’t get a hold of them and they just kind of disappear.”

Homdus says he’s seen mug shots of former BFA students on the Stockton Police Department’s Facebook page. “I’ve never seen a student on there who finished the program, but I’ve seen a lot of students who have not finished the program. You’ve got these guys that are in there for burglary or sometimes violent things.”

Stockton’s homicide rate hit an all time high of 71 in 2012, up from 58 the previous year.

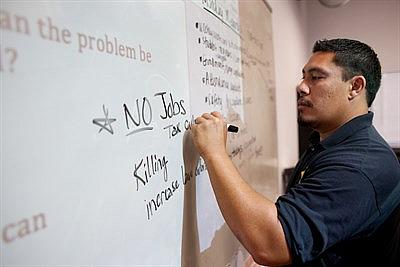

BFA teacher Luke Homdus leads his class in a writing assignment on how to improve Stockton. Andrew Nixon/Capital Public Radio

“It’s a rough place,” says Homdus. Stockton became the largest US city to declare bankruptcy in 2012. “(Students) are always telling me that ‘Stockton’s crazy.’ That’s a word they’ll use a lot…crazy.”

“A lot of people think kids these days just don’t care,” says BFA construction teacher Darren Branch. “But if you ever sit down and you have a serious conversation with one of these students, it matters to them. I think the issue is they just don’t feel that they can do anything about it, so they just go with the flow.”

Going with the flow, however, is not for Roosevelt. “I think about Stockton every day because I live here. I drive the streets.” And driving the streets of Stockton is very different from driving in a more affluent community, Roosevelt realized during a recent road trip to Dublin, California.

“I’m thinking to myself ‘these are nice streets,’ because I can feel the difference in my car. It’s like when I get to Stockton, the streets are not paved correctly, they’re not smoothed out…it’s all uneven.”

Roosevelt even thinks about trying to get a job with the City of Stockton. “And even if I don’t get a job for the city I’m still going to commit to doing community service. I still want to help the city. This is my home and if I can’t do anything with my home then I’ve pretty much failed.”

KEEPING THE FAITH

It took about a year for Roosevelt to get over the trauma of his father’s death. In that time he existed in a kind of limbo, playing video games, hanging out with friends. But Roosevelt also went to church. A friend of Roosevelt’s cousin took him to the Lighthouse Revival Center, a Pentecostal church in Stockton.

“It actually helped keep me out of trouble because there were times when I thought ‘I can go out and smoke weed and drink.’ But (church) made me realize that’s not something I should be doing. It doesn’t help anything.”

Roosevelt Webb practices singing at his church, Lighthouse Revival Center. Andrew Nixon/Capital Public Radio

Roosevelt occasionally sings in the church’s choir and he convinced his mom to attend services. “I knew if I could get my mom to go back to church,” says Roosevelt “then the family would soon follow.”

Mike Hernandez, the pastor at Lighthouse Revival Center, says he and his wife have “adopted” Roosevelt into their family. “I told his mom that in our family, he is Roosevelt Webb-Hernandez. We’ve made it a point to raise him just like his mom is raising him but teach him the ways of the Lord.”

“Roosevelt had it rough,” continues Hernandez. “He and his family have gone through struggles. But Roosevelt did not want to be out in the streets, did not want to be part of a gang, did not want to get into drugs. And when I see someone with that type of potential, it’s something inside of me that wants to help him out.”

Hernandez grew up in the 1960s and ‘70s in the small town of Galt, which is about a 20 minute drive north of Stockton. He’s lived in Stockton for about 30 years.

“I’ve seen Stockton go downhill,” says Hernandez. “A few years ago, houses stopped selling, businesses started closing down, layoffs skyrocketed, the unemployment rate just zoomed up.”

But Hernandez says he’s never given up on the city. “I love Stockton. I don’t plan to move. Stockton is full of wonderful people. There’s just a small percentage of the population that has given Stockton a bad name.”

Hernandez notes that the Stockton Police Department reported a 60% drop in homicides during the first half of 2013 compared with the same period last year.

“I do know that (police) have a long way to go. But the fact is that there is progress. We see it out on the streets. And when you see it out in the streets, you have to believe it’s also happening inside the school system where things are beginning to turn around.”

Hernandez says the city has a lot of potential. And potential is also a word he uses to describe Roosevelt Webb.

“When he gets that diploma there’s going to be a celebration. Not only in our church but in his home among his friends that Roosevelt did it – ‘if Roosevelt can do it, then I can do it; if Roosevelt can do it, then my son or daughter can do it.’ And so there is a lot of potential in him getting that diploma.”

But celebration day is still about eight months away. Roosevelt has entered his final year at BFA. If he sticks with the program, Roosevelt will get a high school diploma in May of 2014.

Roosevelt Webb wears a bracelet from his school, Building Futures Academy. Andrew Nixon/Capital Public Radio

Roosevelt is thriving on the personal encouragement and family atmosphere he gets fromthe staff at Building Futures Academy and Pastor Hernandez. He gets the one-on-one connections that were lacking during his years at a traditional high school.

“If I don’t show up (to church), they’re always wondering where I’m at,” says Roosevelt. “I get phone calls from (Pastor Hernandez and his wife). That’s just like YouthBuild. If I don’t show up one day, they’re going to call me – ‘where are you?’ That makes a big difference.”

In fact, it’s made all the difference for Roosevelt Webb.

[This story was originally published by Cap Radio.]

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.