Fighting the good fight: Can CalAIM assist LA’s mentally ill homeless?

This story was originally published in Our Weekly with support from the 2022 California Fellowship.

Our Weekly

California has been wrestling for decades with an ever-increasing homeless population. From the Bay Area to the Los Angeles Basin, the number of unhoused persons grows exponentially each year. Now a fledgling program is striving to combat the crisis in an effective way by harnessing forces from Medi-Cal. It can’t arrive any sooner as the homeless epidemic has touched practically every community statewide, every news cycle, every political campaign, and every individual going about their day in the public square.

CalAIM (California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal) is a $6 billion initiative stretched out over the next five years to address the social forces shaping health. It’s designed to help meet the social needs of many of the state’s most vulnerable residents. Many working with the Los Angeles’s homeless population hope the new program will offer a solution to mentally ill individuals living on the streets.

CalAIM is the culmination of years of research showing that social factors — often beyond individual control — can have a significant impact on a person’s quality of life and certainly medical care. Its large package of reforms is aimed at (1) reducing health disparities by focusing attention and resources on Medi-Cal’s high-risk, high-need populations. (2) Restructuring behavioral health service delivery and financing. (3) Transforming and streamlining managed care and, (4) Federal funding opportunities with a focus on inpatient mental health services.

In the latter instance, persons with an ongoing severe mental illness — as well as those in the midst of a “severe emotional disturbance” — would be cared for during a short-term stay in a psychiatric hospital or a residential mental health facility.

“It’s about making it more integrated and seamless for [Medi-Cal] beneficiaries,” said Jacey Cooper, California state Medicaid director. “For someone who is vulnerable, it’s making sure the right services and supports are being offered to them.”

Cooper highlighted a number of specific initiatives and services of CalAIM, among them managed health care plans, or a “person-centered” strategy that includes assessments of each beneficiary’s health risks and health-related social needs. This approach, she said, centers on a focus on wellness and prevention; it provides care management/transitions across all delivery systems.

“Prior to CalAIM, there was no full continuum of care for the homeless,” Cooper explained. “There are teams on the street now to look after and better monitor behavioral health needs. CalAIM is designed to help get more persons housed, to help with medical care and with hospitalization. We recognize the need for services within the homeless community. CalAIM can help break down those barriers.

The initial reforms are underway. In the coming months, specific timelines or “go live” dates for stakeholders will be announced.

Paving a path to good mental health

One of the programs in Los Angeles County helping to “break down the barriers” that separate the homeless population from services is HOME (Homeless Outreach Mobile Engagement). The program is operated by the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health (DMH) in conjunction with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. They conduct regular — often daily — check-ins, bring the homeless basic supplies, and collaborate with community partners to organize engagement efforts.

“Our teams are out there day after day to help our hardest-to-reach individuals, including many who don’t think they need help,” said Aubree Lovelace, HOME program manager.

Lovelace is hopeful that the CalAIM program will make it easier to connect the people she meets on the street with state-funded mental health services.

As it stands, the sheriff representatives work to establish trust with clients, while the mental health department staff works with these identified clients to connect them with mental health and medication support, crisis intervention, and targeted case management services.

Through HOME, homeless persons can apply for benefits, receive housing placements, and receive assistance to help them stay sheltered as they continue to work on their healing and recovery. The DMH estimates that about 26% of people experiencing homelessness in LA County have a diagnosed mental illness.

“We’ve been able to make change and save lives whereas before we would watch people pass away on the streets because we were limited in what we were able to do,” Lovelace continued. “We have more community partners now. It takes a lot of people and collaboration to serve this community. The pandemic posed a challenge, but we continue to work every day on-site out in the field to provide much needed services to the most vulnerable citizens.”

Putting ‘people’s needs’ first

Cal-AIM was originally proposed in January 2020 but was withdrawn in May of that year because of the COVID-19 pandemic. California Gov. Gavin Newsom reintroduced the program for the 2021-22 budget with hardly any difference in policy reforms except in relation to the proposed implementation timeline.

Some components of CalAIM are expected to result in new state costs. Officials believe these to be minimal and only in the short term.

Since January, they’ve spent about $530 million, and by next summer the amount is projected to increase to just over $750 million. The increase is reflective of the shift from half-year to full-year funding. The dollar amount is estimated to decrease to about $420 million during the 2023-24 fiscal year. Another decrease is expected in 2024-25 because of the expiration of certain limited-term funding components (i.e. managed care plan incentive payments). Newsom said the primary goal of CalAIM is “guaranteed healthcare for all Californians.”

“We’re taking unprecedented action to rebuild California’s mental and behavioral health infrastructure,” Newsom said. “This is about getting folks the help they need to get out and stay out of homelessness. We’re doubling down on those efforts with significant investments in mental health and substance abuse treatment to get vulnerable people off the streets.”

Here’s the objective: First, CalAIM will put “people’s needs” at the center of care. It is designed to provide coordinated support to meet each Medi-Cal beneficiary’s physical, developmental, behavioral, and dental health needs while offering long-term services and health-related social support mechanisms.

For the homeless battling substance abuse, the program makes available a series of “sobering centers” which are deemed to be alternative destinations for beneficiaries who are found (by law enforcement) to be intoxicated — or worse in the midst of an overdose — and would otherwise be transported to an emergency room or jail.

Dr. Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, a professor of Clinical Internal Medicine at UC Davis, was part of a team that embarked on “Healthy People 2030,” a study to determine what are the best practices to “attain the highest level of health for all people.”

He said CalAIM’s goals are in line with what he found to be beneficial for improving mental healthcare across the board.

“The most important goals [in encouraging healthcare equity] would be to improve community engagement while demonstrating marked improvement in the quality of care, improving the customer experience, outcomes and reducing overall cost,” Aguilar-Gaxiolan said.

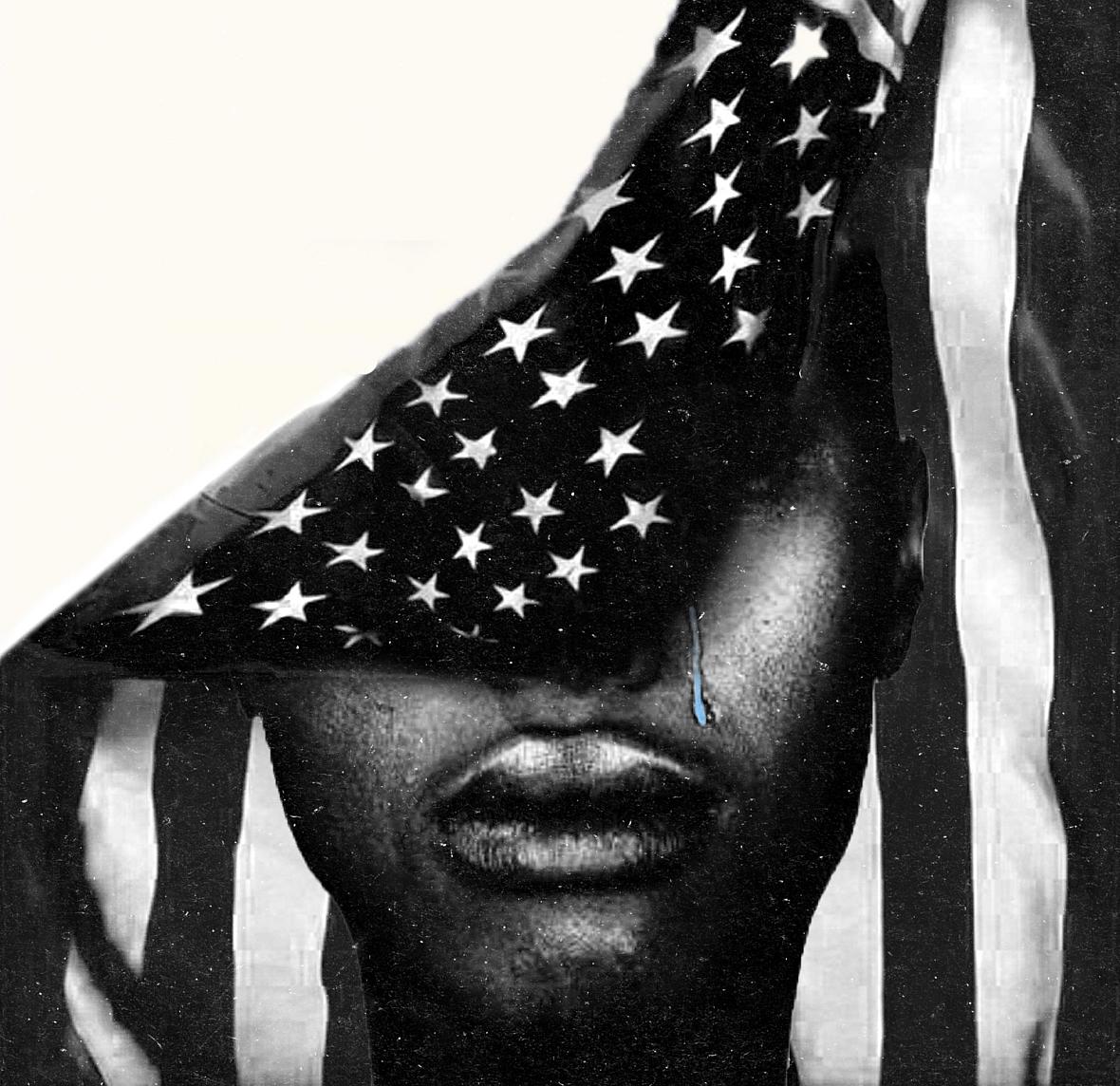

Stigma of mental illness in Black community

Providers, both at the state and local levels, say that the homeless community has a dearth of trust in authority. Many persons have bad experiences with law enforcement — or with those in any official governmental capacity — and therefore are skeptical of any “treatment” programs/services that may be offered to them. Healthcare providers suggest this is particularly true of African-Americans who have witnessed a history of medical and/or psychological mistreatment.

African-Americans share the same mental health issues as the rest of America. There are greater concerns in the Black community, however, because of systemic racism, prejudice, ignorance and economic disparities related to healthcare.

There also remains a fear that they will not receive adequate help because their therapist is most often White and may not understand their particular needs.

Aguilar-Gaxola said the best method to gain trust among the mentally ill is to simply listen.

“That is vital,” he explained. “You must hear their story. Have empathy for their situation. The homeless population is misunderstood. Building trust is instrumental in reducing discrimination in health services.”

For at least 56 years, Medi-Cal has remained a complex subject. As of 2022, some 14 million people are enrolled in Medi-Cal (about one in three Californians). The Cal-AIM expansion is anticipated to bring in another 235,000 enrollees by summer 2022. In short, services in the program are delivered through a variety of systems, the largest of which is “managed care” which serves more than 80 percent of enrollees.

Managed care plans are responsible for arranging and paying for most health care services like primary care and hospital inpatient services. Los Angeles County, for instance, operates a “distinct delivery system” for treatment to Medi-Cal enrollees with severe mental health conditions and also for personal care services.

Despite the lofty goals of CalAIM, it has been reported that more than 2.3 million Californians remain uninsured for reasons ranging from yearly income exceeding the threshold for acceptance, or simply being ineligible for coverage — a primary pitfall for undocumented persons.

Helping to better navigate Medi-Cal

CalAIM would shift Medi-Cal to a “population health approach” by prioritizing prevention, addressing social drivers of health, and transforming services for communities who historically have been under-resourced while facing generations of institutional racism in the healthcare system.

Included will be specific initiatives on equity which will be designed to provide equal access to health and well-being for persons transitioning from incarceration to community re-entry, from homelessness to housing, and from institutional to home-based care.

Because Medi-Cal is so fragmented, some enrollees have had to access six or more delivery systems, thereby making it difficult to navigate across providers and services. CalAIM’s “Enhanced Care Management” (ECM) feature would assist in developing individual plans with specific health providers. These providers are often more familiar with the enrollee and can better connect them with clinical and non-clinical services and resources that help persons meet their health goals.

This kind of streamlining is already happening on a local scale in Los Angeles, through the “Just in Reach/Pay for Success” program which, over the past two years, has reduced spending on county services (e.g. emergency shelters, hospital care). The program has helped to offset between 50 and 100% of the cost of providing housing and needed health services to participants. That’s about $6,200 saved per participant each year.

In an August 2022 report, the Rand Corp highlighted the success of the initiative.

“The Just in Reach/Pay for Success program appears to significantly reduce participants’ use of county service,” said Sarah B. Hunter, the study’s lead author. “The program may prove a feasible alternative — from a cost perspective — for addressing homelessness among individuals with chronic health conditions involved with the justice system in Los Angeles County.”

CalAIM hopes to have a similar impact by working to help align funding, data reporting, quality, and infrastructure to mobilize and incentivize progress toward “common goals.” Also, CalAIM may be able to help reduce variation across counties and plans. Officials hope the initiative will foster more recognition of the importance of local innovation and supports, along with community activation and engagement.

More flexibility for healthcare plans

CalAIM utilizes “community supports.” These mechanisms allow for housing access to incorporate things like basic hygiene to medically tailored meals. This is said to play a fundamental role in meeting the needs of beneficiaries for health and health-related services that address social drivers like food insecurity and general social support. As an example, a homeless person diagnosed with cancer may not be able to tolerate chemotherapy if they have no safe play to stay, rest and recover. Traditional Medi-Cal has only provided coverage in a nursing home or hospital, often more than what may be needed. If successful, various health plans would now have the financial flexibility through CalAIM to meet the needs of members in new, more patient-centered ways.

There are also services for people who are incarcerated and, among the homeless population, those who suffer from a chronic illness and/or behavioral health condition like mental illness or substance abuse. People transitioning from incarceration face increased risk of adverse health events. This is particularly true of those battling substance abuse of which research (New England Journal of Medicine-2007) has indicated are 129 times more likely than the general public to die of a drug-involved overdose or commit suicide within two weeks after release.

There is hope that CalAIM can help ease the transition back to the community and prevent health and behavioral health complications — including the risk of post-release homelessness.

Addressing behavioral health is a key component of CalAIM. Among the homeless, mental health services are desperately needed, but it is difficult and sometimes impossible to receive adequate services when living on the street.

Presently, the California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) is proposing reforms to ensure that patients can get treatment wherever they seek care. Sometimes this can be done prior to a formal diagnosis of mental illness and therefore provide a mechanism for reimbursement to managed care plans based on the type of care provided.

In the above circumstance, CalAIM would help to facilitate the integration of speciality mental health and substance abuse services at the county level into one behavioral health managed care program. CalAIM would also include a new benefit — ”contingency engagement” — specifically for persons with a substance abuse disorder.

The interconnection between mental illness and homelessness

Mental illness can contribute to homelessness when symptoms become so severe that the person can’t function. Specific symptoms of mental health disorders, such as manic state of bipolar disorder or the psychotic symptoms and paranoia of schizophrenia, can make it difficult to care for oneself and ultimately isolate the person when others don’t know what to do.

The DHCS has reported that half of people who have a mental illness also use illicit substances, often as a way of coping with their illness. As well, according to DHCS findings, half of people who use substances have some type of mental health condition. In order to try “something different,” DHCS has integrated oversight, administration, and payment of specialty mental health and substance use disorder services into one contract between themselves and local counties.

DHCS works with the California Bridge program. Their agenda is to develop hospitals and emergency rooms into primary access points for substance abuse treatment and/or acute symptoms of substance use disorders. They want to better train and educate clinical staff on how to integrate care (e.g. identifying opioid use disorder) in managing and connecting patients with ongoing treatment and care. Through CalAIM, DHCS could make it possible for some patients to receive multiple services in one coordinated location.

Conversely, homelessness can contribute to mental illness because of the severe distress caused by living on the streets. The interconnection between homelessness and mental illness is multifaceted. There is increased urgency among service providers to dispel the fallacy that homelessness and mental illness must forever coexist.

A prime example of the “urgency” are the roughly 2,600 people who make their home along Skid Row in Downtown LA. At only 2.70 square miles, it has been suggested that some 40% of persons there suffer from mental illness.

“The homeless crisis has reached a breaking point in Los Angeles,” said Rev. Andy Bales, chief executive of the Union Rescue Mission. “We’ve left far too many people languishing on the streets for far too long. Mental illness is a primary concern we have at the mission. The longer you leave people on the streets, the more danger they’re exposed to, the more dangerous it is to everyone else.”

CalAIM could potentially reduce health disparities, specifically among persons in historically underserved communities. This is particularly true in terms of mental illness.

Health disparities exist when one population experiences systematically worse health outcomes than another group. For example, homeless persons with mental illness are frequently associated with medical comorbidities for a variety of physical and/or mental health conditions. This, in turn, results in excess mortality.

Rejecting the ‘one-size-fits-all’ to managed healthcare

Mental health experts suggest programs like CalAIM could effectively reduce disparities by improving the health of those persons who regularly suffer from worse outcomes. The homeless population typically tops this list.

“Many of [the homeless] will say they are doing fine, even as they are dying on the street,” said Dr. Johnathan Sherin, former director of DMH. He referred to a condition known professionally as “Anosognosia,” meaning that a person is unaware of their own mental health condition and can’t perceive their condition accurately.

“It is important that we engage these persons — resources first — and continue to engage the individual to realize the best outcome not only for that person but for the community as a whole,” Sherin explained. Admitting that there are “no easy solutions,” Sherin pointed to the value of determining “who’s out there” (programs/policies/facilities to serve the mentally ill homeless) and proceeding immediately to address the needs of that population.

“We’ve got to do something to break the log jam,” he said. “We’re decades of being negligent. We have to look out for one another, and our elected officials have to be part of the solution.”

Two years ago, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors approved a motion directing DMH to deploy the HOME teams to pilot “street-based” treatment and clinical oversight to help the “most vulnerable residents” get on the path to recovery. While this was at the beginning of the pandemic, DMH found that a significant number of deaths were due to “preventable or treatable” medical conditions, including mental illness exacerbated by chronic substance abuse.

LA County Public Health reported more than 1,000 homeless persons perished during the early stages of the pandemic, of which some 30% suffered from mental illness.

The objective of CalAIM is similar to that of California’s Mental Health Services Act (Senate Bill 970) in addressing homelessness and hospitalizations. Here, counties are held accountable for meeting these challenges. The bill is modeled after a “continuous quality improvement” approach to track the progress and steadily improve the lives of homeless persons with severe mental illness and substance abuse disorders. Like CalAIM, SB-970 rejects the “one-size-fits-all” approach in funding county-based programs to help them meet their individual goals.

Various homeless counts often in conflict

Many California counties have adopted innovative approaches to expand and improve behavioral health services. CalAIM is also designed to more accurately gauge accountability in measuring progress or achieving specific outcomes. Maggie Merritt, chief operating officer of the Steinberg Institute, has for the past seven years studied and addressed the challenges to enact sweeping improvements to California’s mental health policy.

“We continue to see people living with severe mental illness suffering on our streets or cycling through hospitalizations, incarceration with no long-term recovery in sight,” Merritt said. “CalAIM has the potential to assist greatly in providing early intervention and offer the service needs of persons with — or at risk of — serious mental health and substance use conditions.”

How many homeless persons in LA County suffer from one or more forms of mental illness? It depends on who you ask. A federally mandated count in 2020 found that about 67% of the homeless population were either “reported” or “observed” suffering from mental illness or substance abuse. But the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) put the number at just 29%.

The Los Angeles Times researched the topic and revealed that PTSD affects 51% of the estimated 70,000 persons living on the streets. LAHSA would later release a statement regarding the disparity: “The challenges faced by people on the street who are experiencing mental illness or substance abuse does need to be an important part of the conversation,” the agency concluded.

HOPICS makes strides in South Los Angeles

The California Policy Lab at UCLA took a look at the level of mental illness among the homeless, this time with a more “critical lens.” They utilized a different set of data from a much more comprehensive questionnaire known as VI SPDAT (Vulnerability Index–Service Protection Decision Assistance). It’s mostly used to identify who should be recommended for housing/support intervention. Their findings suggest that mental illness was a “concern” among 78% (nationwide) of homeless persons.

With LA County serving as the nation’s de facto hub of homelessness, both LAHSA and Times surveys may have fared poorly in determining an accurate local number connecting homelessness and mental illness.

As stated, a prime objective of CalAIM is to meet people “where they are,” but Los Angeles County has made only incremental steps because of a lack of practitioners and people doing so on a consistent basis. There are several organizations in LA County working to help remedy this barrier. HOPICS (Homeless Outreach Program Integrated Care System) works extensively in South Los Angeles to help meet the behavioral health needs of the homeless.

Similar to a stated objective of CalAIM, HOPICS is tasked with assessing the factors/barriers that may circumvent individuals from accessing needed services and effecting change in their lives. With three offices in South LA, and another in nearby Compton, HOPICS interacts each week with hundreds of homeless persons in the inner-city in delivering outreach services (e.g. food, water, blankets, etc.) and importantly access to healthcare services including CalAIM. Officials at HOPICS commended the ideals of CalAIM in helping to shine a light on the emotional, psychological, mental, physical and social “stressors” afflicting the homeless.

“Housing and access to medical care are two of the most important services that can be offered to the homeless community,” said Ericka Battaglia, manager of community engagement and social impact for HOPICS. They interact each week with hundreds of unsheltered persons in the inner-city in delivering needed outreach services and, importantly, access to healthcare services to include CalAIM referrals.

“Among the challenges for us is to gain the trust and faith among the homeless to be receptive to our services,” Battaglia explained. “So often individuals will shy away from help because they’ve been subjected to so much indignity and mistreatment. We want every person we come across to know they will be treated with dignity and respect. We accomplish this by working together and sharing information and resources to achieve a common goal. Our daily charge is to help people regain a foundation of hope for a new day.”

The homeless continue to expand statewide. Along with singular destitution, this expanding community of men and women bring with them a myriad of health concerns that are often no fault of their own. It’s an “all hands on deck” continuum from the most powerful levels of county and state government, to private organizations and even the faith community.

CalAIM has a tough hill to climb to reach these individuals. If all goes well, a much maligned government agency may provide a level of solace in retrieving these men and women from the mean streets back to the safety and security of a home, regain their confidence, and retain good health.

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 California Fellowship.

Our Weekly coverage of local news in Los Angeles County is supported by the Ethnic Media Sustainability Initiative, a program created by California Black Media and Ethnic Media Services to support minority-owned-and-operated community newspapers across California.