FORECASTING AN EPIDEMIC: Does weather hold the key to predicting valley fever outbreaks?

Dust storms, like this one in Fresno, can help distribute the fungal spores that cause valley fever.

(Craig Kohlruss/Fresno Bee)

[Click HERE for Spanish version.]

When a punishing drought besieged California in the late 1980s, relief came with 30 days of rain in 1991 — dubbed the March Miracle because of how it revived the state’s agricultural economy.

Those significant swings in the weather may have had another consequence, though. The next year, Kern County health officials counted more cases of valley fever than ever before, with roughly 3,342 diagnoses and 25 deaths. By contrast, a decade earlier in 1982, fewer than 200 people were diagnosed with the disease and seven died.

In the quarter century since, researchers and public health officials have come to see such dry and wet cycles as predictors of an upswing in the disease. That same weather pattern repeated itself between 2015 and 2016, and yet no one at the state or county level sounded an alarm in California or took measures to prepare for the threat of a valley fever surge.

On the contrary, as recently as August, health officials in Kern County told the Center for Health Journalism Collaborative, a consortium of news outlets brought together by the USC Center for Health Journalism, that the number of cases this year would be lower than in 2015. Health officials did not warn the public of a looming epidemic until September.

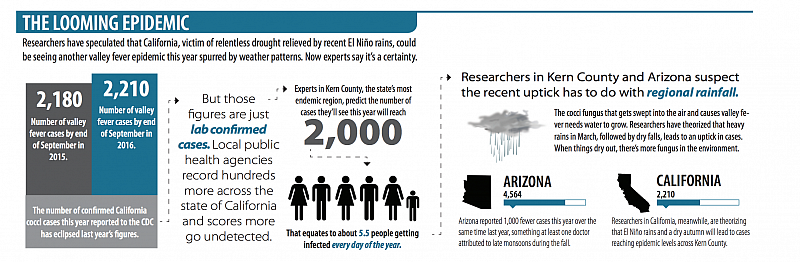

Now officials say that as many as 2,000 people in Kern County alone could contract valley fever by 2017.

EPIDEMIC SURPRISES OFFICIALS

Although there are no state guidelines for when an epidemic should be declared, such a proclamation focuses attention on a disease. And attention is something health care officials say valley fever desperately needs.

Although the cumulative total of illness and death for valley fever is higher annually than hantavirus, whooping cough and salmonella poisoning combined, the disease has historically received comparatively little in research dollars or federal public health attention.

“From our perspective, this has already been the worst year,” said Dr. Royce Johnson, an infectious disease doctor at Kern Medical Center who has spent years researching and treating valley fever.

In Kern County, 890 confirmed cases of valley fever were reported through June of this year, nearly 80 percent more than the number of cases the county sees in a non-epidemic year. At least one person has already died.

Nationally, more than 8,000 people contracted valley fever through early October.. That’s a rate of roughly 28 people every day; the cases are concentrated in just two states: California and Arizona.

So far this year, California has seen 2,210 cases, which is more than a quarter of those reported nationally, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Arizona had more than half of all cases at 4,564. And last year was even worse in Arizona, with more than 7,000 cases reported, including a spike of 138 percent between July and October, compared with the same time period the prior year.

As in California, researchers studying valley fever in Arizona believe weather plays a key role. One theory about Arizona’s dramatic uptick in cases is that a wet winter in 2014-2015 spawned the growth of more valley fever-causing coccidioides fungi, which then spread to animals during the dry early summer season.

Other factors that can affect fluctuations in reported cases, according to the Arizona Department of Health Services: the migration of susceptible people to higher-risk counties in Arizona; increased recognition and testing by health care providers; increased awareness among the general public, and an increase in the number of people with weakened immune systems due to aging.

The biggest spike this year was in September in California, where 20 new confirmed cases were reported for the week of Sept. 19, an 80 percent increase over the previous week, according to the CDC. Arizona saw a 9 percent jump.

Only then did Kern County health officials begin warning the public to exercise caution, but they hesitated about calling it an epidemic. Now they are doing so.

PREDICTIONS NOT PRECISE

Valley fever, also known as coccidioidomycosis, starts with breathing. Fungal spores embedded in dry dirt throughout the San Joaquin Valley, Arizona and other parts of the Southwest get swept up in the wind. If inhaled, those spores become lodged in the lungs. Sometimes the body fights the infection and a person becomes immune to the disease, which is the case for most people. But in other cases, the spores take root and move from the lungs to other organs, leading to a lifetime of health problems and, in rare cases, death.

Cocci, the fungus that breeds the disease, needs water to grow and heat to spread its spores.

“During the rains, the fungus proliferates in the soil,” said John Galgiani, director of the Valley Fever Center for Excellence at the University of Arizona. Then, he explained, a larger number of spores end up in the air when the soil dries.

Every seasoned valley fever researcher says the same thing. But that knowledge has not translated into accurate predictions of trends in valley fever cases. Such forecasts could lead to early warnings for public health officials, care providers and the public.

This summer, public officials charged with monitoring diseases like valley fever believed that the old pattern of dry periods followed by rains would not lead to more diagnoses.

“My gut feeling is no,” Kirt Emery, a Kern County Department of Public Health Services epidemiologist told the Center for Health Journalism Collaborative in June when asked if weather patterns could lead to another epidemic. A few weeks later, though, Emery’s department issued a press release saying that, indeed, new cases were on the rise again.

Despite a bout of dry weather throughout California, Emery and others had not been predicting a rise in infections because reported valley fever cases were decreasing for most of the year.

Meanwhile, in Arizona, numbers of reported cases fell by about 1,000 this year, something Galgiani attributes to a wet summer monsoon season stretching into September and October — the peak months for valley fever. Those numbers in Arizona also might be skewed, researchers caution, because of a series of changes in reporting standards by a major commercial lab.

Symptoms can present anywhere from one to three weeks after exposure, though, and

doctors often misdiagnose the disease for the first several weeks, so it can take time for diagnoses to catch up with the course of an active epidemic.

SCIENCE SLOW TO CATCH UP

Despite understanding the basic weather pattern that may lead to an outbreak, scientists still have no reliable way of mapping out just how many fungal spores are growing or blowing through the air. It also remains impossible to track how many people develop immunity to the disease after being exposed. Each wave of a valley fever outbreak should, in theory, immunize a significant proportion of the population to the disease.

And even though researchers have been observing these weather patterns for decades, they have been slow to publish findings in academic journals about the correlation between weather and valley fever, a topic under investigation since the 1940s. Why does that matter? Because publishing provides the evidence needed to set policies and priorities.

Scientists and public health officials agree there haven’t been enough large-scale studies on why and when valley fever cases spike. Federal or state research dollars aren’t there to mount a major study and few researchers focus on the topic as a result.

Those studies that do exist offer divergent findings on the connections between weather patterns and spikes in valley fever. In Arizona, which has one strain of cocci, findings have shown a strong connection between climate patterns and incidence, while in Kern County, which has another strain, only a weak connection has been found.

Despite that, Ronald Talbot, a retired Kern County Department of Public Health Services epidemiologist and lab director, said that weather has consistently proven to be the most predictive factor in epidemics.

He studied weather patterns during his career and theorizes that in years when the region receives more than four inches of rainfall in February and March, the incidence of valley fever increases in September and October.

“I never came across anything else that was even suggestive,” Talbot said.

Stephanie Innes and Kerry Klein from The Center for Health Journalism Collaborative contributed to this story.

Next in this series: Promise and challenges with a new skin test for valley fever.

For more stories in this series, click here.