Full ‘Court’ Press Black Advocates Bridge The Gap In Sacramento’s Child Welfare System

The story was originally published by The Observer with support from our 2025 Child Welfare Impact Reporting Fund

Photo: Roberta Alvarado

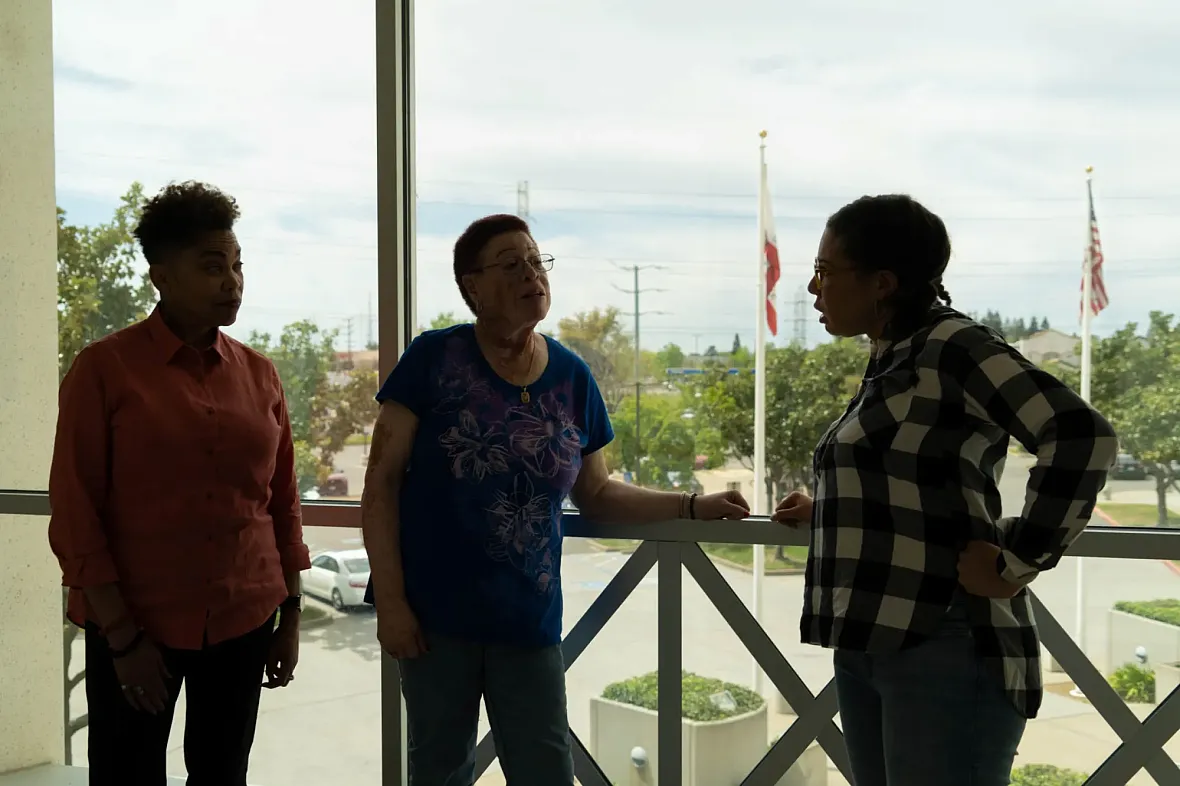

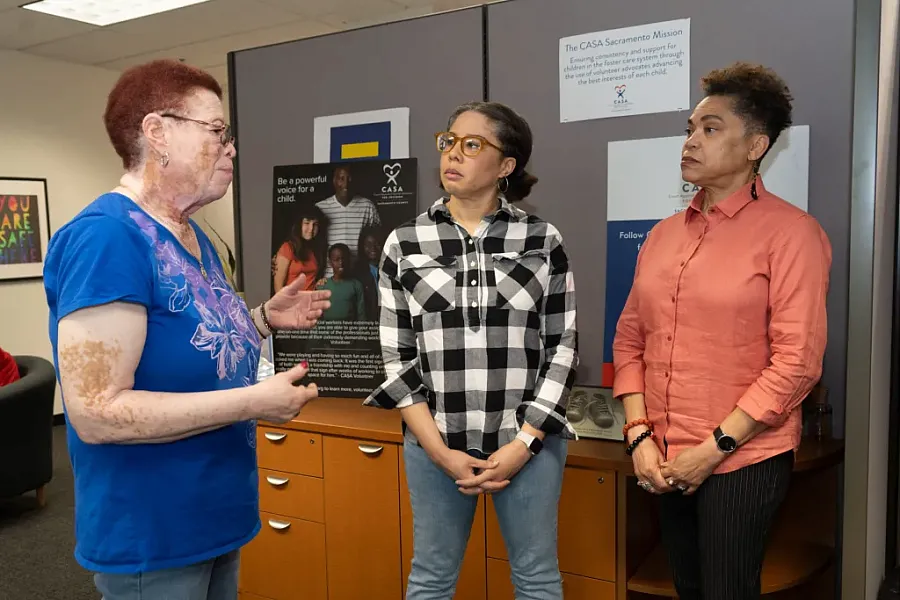

Navigating the child welfare system poses a significant challenge for young people. Three local women – Danielle Dace, Simone Youngblood and Odette Crawford – are dedicated to helping them.

As past and present court-appointed special advocates (CASAs), Dace, Youngblood and Crawford have provided one-on-one support to youth in the system. Traditionally, CASAs were mostly middle-aged, retired white women; these three Black women are deeply committed to serving, particularly given the disproportionate number of Black youth involved.

From left, Odette Crawford, Simon Youngblood and Danielle Dace have all served as Court Appointed Special Advocates, seeking to aid Black youth in navigating the child welfare system and their related needs.

Photo: Roberta Alvarado

“The core mission of a CASA remains the same,” explains Dace, CASA Sacramento’s director of training and recruitment. “It’s about being a consistent, stable and supportive adult in a young person’s life.”

The demographics of CASA volunteers are changing. While 80% were previously older white women with ample time, Dace notes an increase in volunteers in their 20s alongside those in their 50s and 60s. There is a specific need for more Black CASAs, as youth often prefer a volunteer of the same race.

“We aim to be more inclusive,” Dace says. “Representation matters to these kids. It’s easier for them to open up to someone who looks like them.”

With only 165 active volunteers, most Black youth are not currently matched with a same-race advocate. Youth paired with CASAs are those the court deems in need of the most support.

“It’s teenagers who are going to age out with no support and no safety net, nothing,” Dace says. “Someone along the way – a social worker, a judge – somebody has said, ’This kid needs some help.’ With younger children, parents are generally working to do whatever it is they need to do to get those kids back. With teenagers, not so much.”

A 2023-2024 Sacramento County grand jury called out the county for “failing to meet its obligations” to provide safe and secure living environments for unplaced teens. A local media outlet’s investigation found teens had been housed in less than adequate settings, some in a former juvenile detention center and others in empty county office buildings with no kitchen or showers.

“These teenagers are virtually invisible because they are not a priority in Sacramento County’s foster system,” the grand jury report reads.

Mi CASA, Su CASA

Typically CASAs are matched with one youth at a time, but exceptions can be made.

“Maybe they’ll take on siblings,” Dace says. “So often siblings are separated; they’re not in the same foster home, so in order for them to see each other, a CASA may take a sibling set. But in general, it’s a one-on-one relationship, so there’s not so much chance for burnout and feeling overwhelmed.”

Danielle Dace, CASA Sacramento’s director of training and recruitment, aspires for more Black men to participate in the program.

Photo: Roberta Alvarado

Dace came to CASA Sacramento as a volunteer advocate in 2009 and joined its staff in 2016. There were around 4,000 kids in Sacramento County foster care back then. According to county data, the foster care population has decreased by 26.5% over the past five years. Black children had the second largest decrease during that time period. Of the 899 children aged 0-17 in foster care as of March 16, 32% were Black.

“It’s still very much disproportionately African American and Hispanic,” Dace says.

When she became an advocate, Dace wanted to be matched with an African American girl. Over a seven-year period, she advocated for four. She helped two of them finish high school.

“Graduating high school is a big one because so many foster youth do not graduate,” Dace says.

According to the National Foster Youth Institute, just 50% of kids in foster care get a high school diploma. An estimated 2%-6% complete two-year degrees, and only around 3%-4% earn four-year degrees. Locally, Sacramento State is working to address this issue by guaranteeing admission to eligible foster youth and providing financial support through its Guardian Scholars Program.

Dace’s first match was not a success story, which left her disheartened. The young woman had experienced significant trauma and refused therapy. She eventually dropped out of school.

“Unfortunately, I believe that she ended up being trafficked and kind of just fell off the radar,” Dace says. Black teens who age out of foster care are at a higher risk of homelessness, incarceration, and other negative outcomes. Despite the initial setback, Dace returned to the program, determined to make a difference.

“I knew that was not that girl’s fault,” she says. “I took a few weeks off, and I came back and I said, ‘OK, CASA program, I’m ready to try it again with another youth. There’s another youth that needs me.’”

Her second match was more successful, as the young woman was actively working through her trauma and seeking support.

Law And Order

Simone Youngblood, a local communications manager, became a CASA in 2022, driven by a desire to work within the legal system and advocate for youth.

“I Googled it, looked it up, and read a little bit about it and thought, ‘You know what? This might be something that could work for me.’ Youngblood says.

Simone Youngblood has been paired as a court-appointed special advocate with African American girls.

She was particularly drawn to the connection between the criminal justice and child welfare systems and saw CASA as a way to bridge that gap. Hearing from foster youth during her initial training sessions was eye-opening.

“Just seeing how traumatizing being in the system could be and is for so many youth who may even enter at a really, really young age, it gave me a lot of perspective on the lack of support they often experience,” she says.

Youngblood emphasizes the importance of being a consistent presence in a youth’s life.

I’m still kind of new at this. I know that there’s a lot of issues with the child welfare system, but my experiences overall have been positive. Working with the lawyers, working with the social workers, I do sense that, as imperfect as the system is, at least the people in the system, based on my experience, really do genuinely care about these kids.”

Simone Youngblood, CASA

“That time you’re serving them for a year, a year and a half, they have so many people that are ‘here to help them and support them,’ but you can kind of become lost in the shuffle. People mean well, and they do their best, and they can only do so much.

“I think that’s the rule of the CASA, that we can have more of that personalized connection with them,” Youngblood continues. “We’re not [social workers]. We’re exclusively focused on them and being able to attend to their welfare, their needs.”

Building trust can take time, and Youngblood has learned to be persistent, even when faced with resistance.

“Even if they don’t respond, just keep showing up,” she says.

She recalls working with a recently emancipated young person who was initially hesitant to engage. It took a year and a half to build rapport, but Youngblood remained committed, demonstrating unconditional support.

All Rise

Frequency of interaction depends on the youth’s situation, with those experiencing instability requiring more frequent visits. Volunteers typically spend 10-15 hours per month on their cases, including meetings with school officials, social workers, and therapists, as well as attending court proceedings. Youngblood values making semiannual progress reports to judges. The reports allow her to present a personal picture of the youth, humanizing them within the system.

“It’s just those little ways of showing them as a whole person with dreams, with goals, with desires,” she says. “That, to me personally, makes all the difference.”

Like Dace, Youngblood has been paired exclusively with Black youth. She learned about their disproportionate representation during her CASA training and felt compelled to act.

“It was a no-brainer for me,” she says. “Having grown up around a lot of Black ladies, I see the way that sometimes their voice isn’t always heard and it’s something that frustrates me.”

What’s also disturbing, Youngblood adds, is how often African American girls are harshly judged, even by their own families.

“The youth that I work with, it’s amazing the things that they continue to survive,” she says. “Nobody ever acknowledges that they’re a survivor. I want to be somebody that’s always going to see, recognize, cultivate and represent the best picture of them.”

A recent study found that CASA volunteers spend significantly less time on cases involving Black children compared to those involving children of other races. Local Black CASAs, however, report going above and beyond.

“It’s a lifelong thing,” Youngblood says. “You’re serving for a year, two years, maybe longer. I mostly work with adults, but it’s like, they’ve been in a system a long time before, and it’s honestly that the stuff that’s happened in their childhood, it can take a really long time for a lot of that to kind of unravel.”

Youngblood aims to provide a supportive foundation and be a positive influence in young people’s journeys.

“Even after they turn 21, they know that years down the road, if they call me, if they text me or whatever, I’m open to that.”

Life Skills

Like Dace, former corrections administrator Odette Crawford became a volunteer in 2009. It was three years after her retirement, but having recently overseen state prison inmates, she vividly remembered how the absence of stability and parental support could lead youth to incarceration, inspiring her to work to prevent such outcomes.

After a long career in corrections administration, Odette Crawford wanted to help guide young people in the right direction. Crawford recently was recognized for her continued support of the CASA program.

Photo: Roberta Alvarado

According to the Juvenile Law Center, more than 50% of foster youth will encounter the juvenile legal system by age 17, and a significant percentage of them will be arrested as adults.

Such was the case with the one boy Crawford worked with exclusively during her time as a CASA. He was taken from his mother and stepfather, she says, who were deaf, homeless, on drugs and living along the Sacramento River. She went to court with the young man as they tried to find relatives who could take him in. None emerged. She’d taught life skills to middle schoolers and encouraged him to stay focused on his education and stressed the importance of getting a job when he got older.

“He wasn’t a dummy,” Crawford says. “There just was no one to set an example for him. He was all over the place. This young man was literally lost. It was heartbreaking to hear him say he felt like a piece of crap.”

While Crawford couldn’t use the same no-nonsense language she’d previously used with the prisoners who were under her jurisdiction, the young man listened.

“He knew I didn’t play. We had long, serious conversations,” Crawford says. “The ability to effectively listen is major. Even if you have to analyze and read between the lines. A lot of people forget that.”

Crawford admits she worked “overtime” on her CASA match’s behalf.

“I gave him the love any parent would have given their son,” she says. “He didn’t have that.

“My task was to keep him on the straight and narrow so he could envision what life could be.”

As a young adult, her ward ultimately strayed from the path she hoped for and started getting arrested. When he called her from jail, asking her to bail him out, she did. Crawford even offered him a place to live. However, that arrangement ended when he reportedly stole from her roommate. They stayed in touch for a while, and she knows that he has children of his own now. They lost contact a decade ago.

“I still pray for him,” Crawford says. “I hope he’s OK. I hope his children are OK.”

New Recruits

Dace and others are working to create a more culturally competent system. Following the summer of 2020, marked by the pandemic and protests, Dace heard comments from staff that revealed a lack of understanding about the experiences of youth of color. This prompted her to form a diversity and inclusion committee and implement staff training. They began learning about the history of policing, the school-to-prison pipeline, and the mistrust of social workers in communities of color. “These topics can be uncomfortable for many,” Dace says.

It’s not about personal blame, she says, it’s about providing information so people can better serve children. Some don’t make it past the session that addresses cultural agility.

“It’s a good thing,” Dace says. “If this night is too hard for you, in a room of people that look like you, how are you going to do out there?”

The CASA organization is not without its critics. Two white attorneys, Amy Mulzer and Tara Urs, addressed the historical roots of the child welfare system in a 2016 law review, “However Kindly Intentioned: Structural Racism and Volunteer CASA Programs.”

“The child welfare system sets up themes that repeat over and over,” write Mulzer and Urs. “CASA volunteers are predominantly white, middle-class women. Child welfare-involved families are disproportionately families of color and are overwhelmingly low-income. … The race and gender make-up of volunteer CASA programs is one manifestation of the long historical trend linking volunteerism, child welfare and white privilege.”

In 2023, the Department of Justice investigated the national CASA organization due to concerns regarding its financial management and accountability. Research into the effectiveness of CASA programs is scarce and has had mixed results. Some also argue that the program itself is part of “the system” and is guided by flawed perspectives on what constitutes the “best interests” of vulnerable foster children who are often Black, Indigenous, and from low-income families.

CASA Sacramento has faced budget cuts in recent years and maintains the need for the program, and the lifeline volunteers can be.

Crawford recruits people everywhere she goes, even the grocery store. Dace has had some success in garnering volunteer interest on local college campuses, but there’s still a great need for more Black men to participate. When they walk past her booth, she finds herself frequently imploring them, “Our Black boys need you.”

“If I thought really hard, I could maybe name four African American men that we have,” she says.

Dace recalls trying to recruit a member of a local Black social club, who gave her a resounding no because he “had his own children to worry about.”

“It resonated with me because I totally understand it,” she says. “I get it, but then I said to him, ‘If not you, then who?’”