Cambodian/Khmer Genocide Survivors Heal Through Storytelling

The story was co-published with AsAmNews as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

From left to right: Theary Louneoubonh, her father Saray Meak, Robert Chau, and his daughter Dorothy Chow.

Photo by Theary Louneoubonh

In a studio space in Hayward, Calif., genocide survivor Robert Chau and his daughter Dorothy Chow set up for a new season of their shared podcast Death in Cambodia, Life in America.

A chair holds the door open, and on it sits a box brimming with donuts and assorted sweet and savory pastries from Chau’s bakery distributor.

Readying himself to meet and interview a fellow genocide survivor for the first time, Chau flashes back to the labor camps of Cambodia where he worked as a teenager, when the Khmer Rouge regime led by Pol Pot took control of the country from 1975 to 1979, killing a quarter of the population and tormenting and enslaving many more.

“I just looked up to the sky and prayed I would die, because you suffer so much. You bury your friend and think, you’re lucky,” he said, making shoveling motions with his arms and then pointing downward. “You can’t just forget about it. I tried that for 35 to 40 years. It doesn’t work.”

Young Dorothy Chow with her ba, Robert Chau.

Photo courtesy of Dorothy Chow

Chau is one of 257,203 Cambodian/Khmer people in the U.S. — many of whom are refugees of the genocide. As a successful entrepreneur, he defied the odds faced by his community, which continues to have lower educational attainment and higher poverty rates compared to other racial and ethnic categories in the U.S., when analyzing data disaggregated from the “AANHPI” bloc.

Healing from genocidal trauma is a lengthy path that is hard to navigate, even for those who aren’t struggling just to get by. Old demons continued to plague Chau until an invitation from his daughter to speak out about his painful past changed everything.

After telling his story for the first time and finding some relief from the trauma that he had lived with for years, Chau is urging his peers to do the same before it’s too late for them and their descendants.

Interviewee Saray Meak and daughter Theary Lounebonh, organizing their belongings while Chow surveys the setup.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Robert Chau, left, and videographer Henry Ing, right, preparing for a recording session at a studio in Hayward, Calif.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Robert Chau, showing his baked goods to videographer Henry Ing.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

All hands on deck in preparation for the recording of the first episode of Season 3.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Chau and his daughter are showing the power of storytelling in providing therapeutic catharsis to survivors, as well as a low-barrier point of entry toward healing. In the process, they are reclaiming and documenting community narratives about the genocide so future generations will know how they got to where they are.

Broadcasting the unspeakable

The father-daughter duo got started during the pandemic when Chow asked Chau if he would start a podcast with her, beginning with his story.

When Chow was little, Chau tried talking about his past over dinner. It didn’t feel good, so he stopped, and his daughter avoided asking questions until adulthood.

Chau agreed to her request – he was getting older, after all. He joined Chow at a Costco-purchased folding table and began talking into a microphone about everything his daughter had always wondered about.

Dorothy Chow, co-creator of Death in Cambodia, Life in America, testing levels before a recording session.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Over two seasons and 44 episodes, Chau detailed his harrowing journey. He started with boyhood before the genocide to separation from family during it, toiling in the labor camps, sickness and hunger, and the Vietnamese invasion that replaced the genocide with warfare. He went on to recount life as a refugee in the camps of Thailand, and then as a resettler and entrepreneur in America.

Chau’s quality of life increased immeasurably after this process, even improving his sleep – Chau said that his nightmares have decreased by 95% since participating in his daughter’s intergenerational documentation project.

On the podcast’s website, Chow wrote that, though nearly all of the Cambodian/Khmer people in the U.S. are refugees of the Khmer Rouge genocide, they have “very limited first-hand interviews from the survivors themselves, allowing the narrative to be controlled by those who never lived it.”

After documenting her father’s stories, she went on to interview Cambodian/Khmer academics, authors, poets, and clinicians. Meanwhile, her father beseeched his generation to speak out about their living histories and start healing – he offered himself as proof that it was not too late.

Documenting the story of a fellow survivor

One of the first people to answer the podcast’s call for survivors’ stories were from just outside Atlanta, Georgia – survivor Saray Meak and his daughter, Theary Louneoubonh.

Louneoubonh’s second child, a 15-year-old girl, was starting to ask whether her mother remembered being in a refugee camp. They were the same kind of questions Louneoubonh remembered having for her father but feeling unable to ask.

In addition to wanting her father to heal the way Chau had, Louneoubonh wanted to get answers for herself and her daughter. She reached out to Chow – their conversation turned into an invitation to the studio. Now, here they all were.

The immaculately dressed Meak, with his military background visible in his posture, joked, “I’m handsome, not beautiful,” as videographer Henry Ing clipped Lavalier mics onto the tan utility button-down shirt with a navy blue necktie tucked into his black pants worn with black sneakers.

Videographer Henry Ing putting a Lavalier mic on interviewee Saray Meak.

Photo by Theary Louneoubonh

Chau, sharp in an iridescent red twill blazer over a tee shirt and black jeans, emitted the relaxed assuredness of a self-made businessman as he waited in the wings.

“You have to stay on topic, ba,” Louneoubonh warned Meak, using the Khmer word for “dad,” overlapping with Chow’s instructions to her own ba about how to proceed with the interview.

As the interview commenced, the men were surprised to find that they were from the same hometown of Mongkol Borey. The similarities ended there.

Chau was 12 or 13 when he was sent to labor camps. After witnessing executions and burying friends, he learned to keep his head down.

Saray Meak, left, and Robert Chau, right, during the recording.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Meak was a 21-year-old monk at the outbreak of the genocide and became a soldier overnight to defend the monastery. Afterward, he had to fight for whatever army conscripted him.

He said he had been wanting to tell the truth about his life after finding peace through Christianity. A part of his salvation was hearing even worse stories from other Cambodian refugees at his place of worship.

Though Meak felt he had largely put old anger and fears to rest through faith, a bad cold could still teleport him back to the time he was tied, beaten, and dragged into the river, or when he lay hiding under a house in 1976, ready to die. Sometimes, he dreams that his legs are crossed and he can’t run.

Swan song for intergenerational trauma

Meak told his story steadily and almost unemotionally.

But he kept mentioning a song that he had sung defiantly at one labor camp, somehow leading to his transfer to another camp rather than instant execution. Nobody, least of all Meak himself, knows why he was spared.

The song was by Sinn Sisamouth, a national treasure of Cambodia remembered as the Elvis of Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge, which targeted artists, leaders, and intellectuals first, killed Sisamouth one year into the genocide.

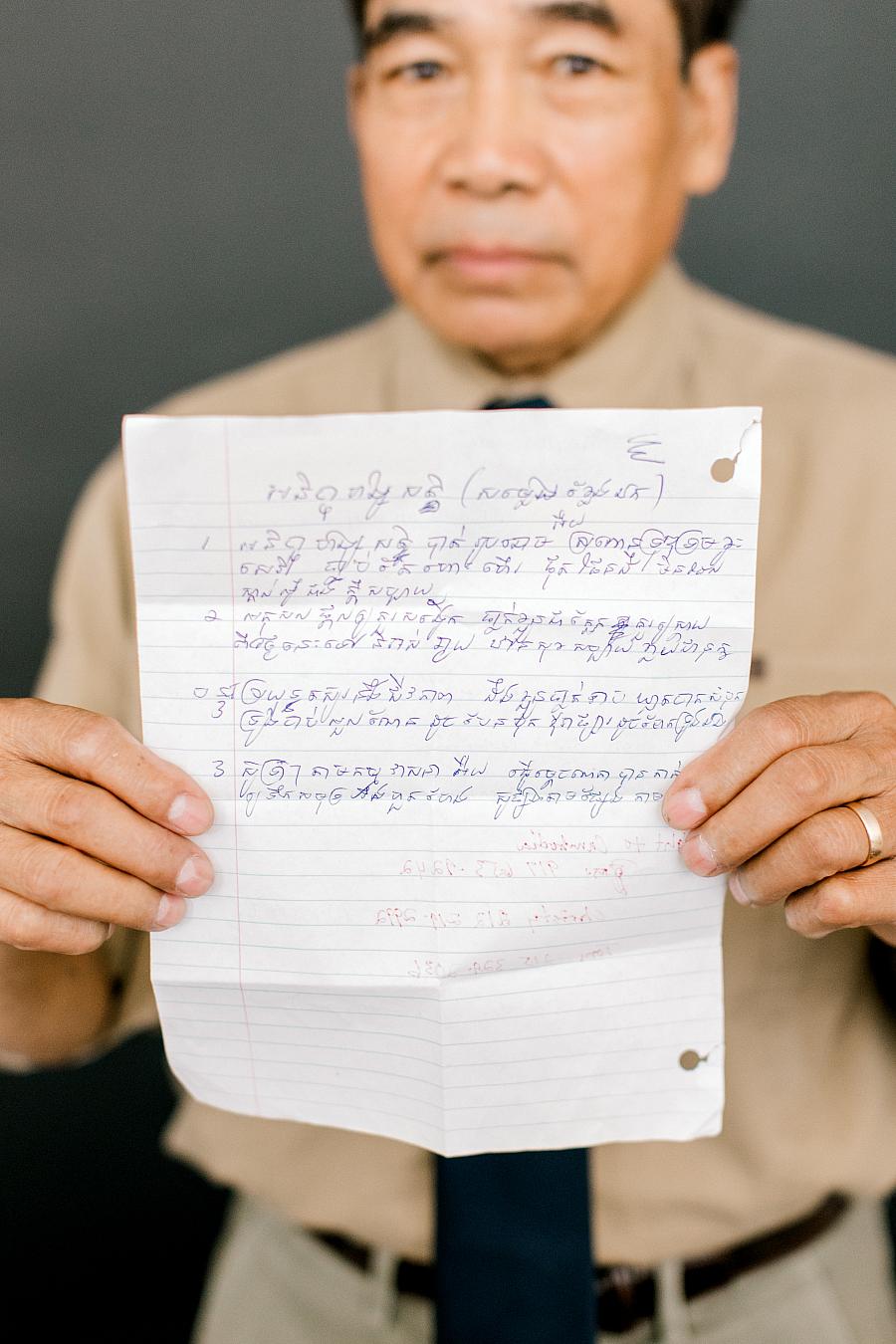

Saray Meak, survivor of the Khmer Rouge genocide, holding up the lyrics of the Sinn Sisamouth song that remarkably didn’t kill him and kept him strong.

Photo by Theary Louneoubonh

The lyrics, about a swan, was an allegory for the political oppression of the kingdom of Cambodia. The verses were so incendiary to the Khmer Rouge that every known copy is believed to have been destroyed. Meak said he was willing to compensate anyone who could find the song in its original form.

Later, another artist rerecorded the tune, but Meak said that the words had changed. He knew this because he sang the song over and over out loud and in his mind. Whenever he got a pen and paper, he wrote down the lyrics. He still did this from time to time, and had a copy on his person, which he unfolded and held up.

Chow asked if he could still sing the song. Meak sang as tears streamed down Louneoubonh’s face:

The pitiful swan,

Its beauty lost

Faded and weak without freedom

It used to soar about the Earth

Knowing nothing but joy

At the end of the recording session, Louneoubonh and crew asked Meak if it had been hard to talk.

“Not really, when you sit with a comfortable man. If it wasn’t this situation here, it would have been impossible,” Meak said, putting his arm over Chau’s shoulders for a photo.

Meak rolled up his sleeves and pant legs to show matching tattoos on his forearms and calves. He had not mentioned these during the recording, but the image was of a compass leading to his mother’s home. He inked the design on each limb so that even if he were to die, even if he were mutilated or dismembered, his mother could identify her son and stop waiting. She was good at waiting and had done so for a brother who was never found.

Meak’s tattoos with directions to his childhood home, which he placed on all four of his limbs during the genocide for identification in case of death and dismemberment.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

When asked if Louneoubonh wanted to take a photo that showed her own tattoos alongside her father’s, she declined. “He’s not proud of my tattoos,” she said, wryly.

Father and daughter did take photos, limbs covered. Chau and Chow joined them a few snapshots later to commemorate this momentous occasion of intergenerational exchange.

Benefitting from storytelling’s therapeutic effects, without the stigma

In a conversation with AsAmNews, Cambodian refugee Pysay Phinith, LCSW, said that telling one’s story has numerous therapeutic effects for genocide survivors, their descendants, and the greater community.

She said that speaking out about difficult times in their pasts and along their journeys actually helps desensitize and distance survivors from the traumatizing experiences in those stories.

“Because it’s not trapped inside you. It’s not trapped into your memory bank, and it’s not also trapped in your body. Trauma can be trapped in your body. But being able to share stories – it becomes a release,” she said.

Dorothy Chow and videographer Henry Ing, getting their cameras ready.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Videographer Henry Ing and podcast co-creator Dorothy Chow behind the cameras.

Photo by Theary Louneoubonh

But to get to the point of getting a survivor of genocide to talk about their past requires a deep relationship built on trust.

Phinith is the program director and wellness specialist at the Korean Community Center of the East Bay (KCCEB) – an organization that expanded years ago to serve diverse immigrant and refugee populations.

She has built trust within her community and others through over 12 years of work in community-based prevention, early intervention, clinical case management and mental health treatment services for Asian and Pacific Islanders. As a Licensed Clinical Social Worker, she also provides case management, social services, wellness support groups, and clinical rehabilitation services to clients of all ages.

An important part of Phinith’s ability to build trust is that she is herself a Cambodian/Khmer refugee, as well as the child of parents who sustained trauma from living through the genocide.

Pysay Phinith, LCSW, right, with KCCEB colleague Manith Thaing at the Pchoum Ben ancestral celebration in San Francisco.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

She grew up within an environment that whiplashed between silence and conflict – a common family dynamic between older and younger generations in her community. Both silence and conflict came from language barriers, cultural differences, and lack of informational exchange between children, parents, and elders about one another’s experiences.

“Sometimes the not sharing is also like carrying that burden so they don’t have to pass that burden on to the younger generation – the pain stops with them,” said Phinith. But, in her personal and clinical experience, she has seen these protective intentions spawn intergenerational trauma instead. Because, while genocide survivors try to leave the past in the past, they continue reacting to and acting upon old trauma responses.

Just one example of undiscussed conflict Phinith experienced in her family was harassment from her father (and, by proxy, brother) if she did not make it home before dark.

“What I didn’t understand was that in Cambodia, execution happens at dark. So, if I don’t come home by four or five, he was already triggered: my daughter will never come home,” she said.

Theary Louneoubonh (R), born in a refugee camp, talks with podcast co-creator Dorothy Chow (L).

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Two daughters of genocide survivors, at ease.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Now working as a clinician who traces back current trauma responses of Cambodian/Khmer survivors to the genocide they lived through decades ago, she often incorporates elements of narrative therapy, a clinical subset of the wider act of story sharing.

In this approach, popularized in the 1980s, mental health professionals work with clients to break down their stories and see that they are distinct from their problems and behaviors. With positive reinforcement of their strengths and values, they learn to “rewrite” future chapters in their own journey.

“We work to help reframe and to help them understand and process what they have gone through. And then through that, we start having the engagement about healing,” Phinith explained.

She said projects to capture the oral histories of genocide survivors is not new. Minnesota Historical Society conducted video interviews of survivors in 1992 for its Khmer Oral History Project, while Digital Archives of Cambodian Holocaust Survivors (DACHS) have been gathering oral histories from survivors around the globe. Last year, the Historical Society of Long Beach launched an exhibition of the Cambodian American 1.5 Generation Oral History Project featuring 15 narratives of survivors who were children during the Khmer Rouge and immigrated to the U.S. as refugees between 1980 and 1986.

Robert Chau, left, and Dorothy Chow, right, in a live-recorded conversation with Sophaline Mao at Sabaidee Fest 2024 in Chino, Calif.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

”Story sharing has been used for many of our cultures for centuries as a way of passing down information, as a way for our younger folks’ generations to learn about history and past and connections,” she said.

Phinith’s own father surprised her when she was in college by mentioning that he had told his story to one of these oral history collections. She has not yet had the chance to find an archived version and hear the story for herself.

She said what is unique about the podcast Chow and Chau share is its foundation in their close family relationship – something that naturally promotes the intergenerational exchange of information that the Cambodian/Khmer community critically needs.

“That relationship’s got trust. And it starts there,” she said.

The early days of Death in Cambodia, Life in America, which started at a Costco folding table.

Photo courtesy of Dorothy Chow

For those who are open and ready, Chau and Chow may be offering a low-barrier entry point toward healing for aging genocide survivors who still fear being stigmatized for acknowledging and addressing mental health challenges.

“What the father and daughter are doing is less stigmatizing, right? If you’re sharing out to the public, you’re not going to therapy. It’s informal, it’s just a conversation. I think that’s more acceptable in our community or to society, to a certain extent,” Phinith said.

Beyond California

Chau and Chow have been going on the road to meet and interview more survivors wherever they are or flying them to the Bay Area to reach more survivors scattered across the country and even the world, far from the disproportionate congregation of Asian communities throughout California.

Chow has been funding travel and production out-of-pocket but has filed for the establishment of the Death In Cambodia Foundation, which would enable the pursuit of funding to sustain and expand the platform.

Months later, Louneoubonh shared her reflections to AsAmNews from her home in Georgia, where she and her siblings grew up “real country,” teased by other refugees for riding horses and speaking with Southern drawls.

“The trip was a miracle in itself,” she said. The occasion of the podcast recording emboldened her to ask her father everything she could on the long plane rides cross country and a trip that included three days in Los Angeles for a wedding in Long Beach, and three days in the Bay Area for the studio session and sightseeing.

Photographer Theary Louneoubonh watches from the wings as her father, Saray Meak, tells his story to Robert Chau.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

She said that witnessing the documentation of her father’s narrative and interacting with other Cambodian community members along the way helped bridge lifelong differences between herself and her father. She was eager for the positive effects to spread throughout the rest of her community, starting with her family.

Phinith said she found the father-daughter podcasting project to be admirable and courageous – something that Cambodian/Khmer families and communities beyond the state of California can not only participate in but replicate.

“It’s also about being able to really encourage other family members to be able to think about, let’s start connecting and communicating and really just wanting to hear your story. Because this is our history – this is our Khmer history. This is something that, whether we like it or not, is our legacy. What did we learn from it? How did we connect with each other? Where can we grow and heal from here?” Phinith asks her community, as it faces the 50th anniversary of the genocide next year.

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of "Healing California", a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California