With Culturally Responsive Treatment, Cambodian Genocide Survivors Heal From Past Trauma

The story was co-published with AsAmNews as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

"A Boy Having A Nightmare."

Graphic by MyUpchar

Nearly half a century after Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge regime murdered at least 2 million people in Cambodia – a quarter of the country’s population – fresh terror lingers in the bodies, minds, and even the dreams of survivors.

Refugees of the genocide who resettled in California have faced difficulties accessing the mental health services they need. Some of these challenges include language barriers and a lack of providers familiar with Cambodian/Khmer culture or the unique traumas affecting the community.

Thanks to dedicated Cambodian/Khmer mental health workers, some survivors have been receiving treatment that recognizes these cultural and psychological complexities. The healing work has been bearing fruit in refugees’ later years.

But top-down healthcare billing structures and poor funding are threatening to iron flat the progress of delicately constructed support systems. Losing these resources could send survivors back to a landscape of insufficient care at the sunset of their lives and leave the next generations without a compass to navigate their own mental health needs.

Not just a bad dream

For survivors of genocide, trauma and soh beu’nt ak-kra (សុបិន្តអាក្រក់), “dream – bad,” remain.

Cambodian refugee and clinician Dr. Arthur Sun, PhD, outside the Pchum Ben ancestral celebration in San Francisco.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

“They’re not just dreams,” said Dr. Arthur Sun, PhD, pacing outside the Pchum Ben Cambodian ancestral celebration held at the foggy seaside Presidio of San Francisco.

Sun is a Cambodian refugee who worked as a clinical service manager and psychological associate at the Southeast Asian Development Center in the Tenderloin of San Francisco.

“As a child, I witnessed people get speared by bamboo traps, intestines all over the trench. I witnessed people get killed and raped right in front of me as a young kid. I witnessed people get blown up by the war between the Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese. I witnessed cattle get blown into pieces,” he told AsAmNews, in a video conversation.

Sun received clinical treatment for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) upon arriving in the U.S. but his nightmares, usually of a Khmer Rouge commander chasing him, persisted.

He turned toward clinical psychology after discovering the people-centered work of Boston-based Dr. Richard Mollica, a pioneer in refugee mental health. Learning the science behind PTSD and what the U.S. veterans’ affairs department calls its “hallmark” symptom of nightmares helped dissipate Sun’s bad dreams.

Boston-based Dr. Richard F. Mollica, considered a pioneer in refugee mental health.

Photo by Carol Tobian

In his work with fellow survivors, Sun has seen the health impacts of unaddressed PTSD intensify with time and age, in the forms of muscular tension, head and body aches, arthritis, visions, chest pains, and the cumulative effects of insomnia due to trauma nightmares.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders identifies nightmare disorder as frequent, intensely disturbing dreams that suddenly wake the sleeper.

Chronic nightmares and night terrors lead to increased heart rate, sweats, decreased oxygen, fear, panic, and insomnia. Other effects include reduced energy and motivation, increased irritation, anger, sadness, and depression, and bodily and mental fatigue.

Sleep disorders overall can also lead to hypertension, gastrointestinal disorders, and heart disease – physical conditions already exacerbated by the prolonged stress and trauma of, say, undergoing a genocide, losing family, and becoming a refugee.

Negotiating with a ghost

The National Alliance on Mental Illness finds that 3.6% – 9 million – people in America have PTSD, while Harvard Medical School estimates that 7% of the overall American adult population and 1 out of 5 children have serious nightmares.

By contrast, Dr. Sochanvimean “Vimean” Vannavuth, PhD, a Cambodian psychologist based in Santa Barbara, cited a 2015 study reporting that 87% of Khmer Rouge survivors continue having distressing memories of the genocide, while 25% report nightmares.

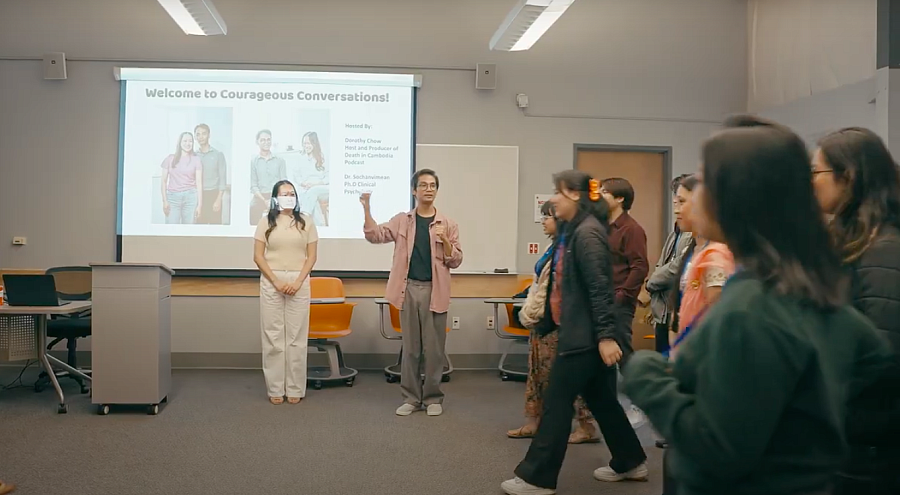

Dr. Vannavuth, chatting with a workshop participant.

Death in Cambodia, Life in America Podcast

And when he began working as a counselor with Cambodian elders after receiving his doctorate degree in clinical psychology from the California Professional School of Psychology in San Diego, he found that 100% of his 68 or so Cambodian/Khmer patients experienced chronic trauma nightmares as part of their PTSD.

These symptoms were intertwined with other somatic effects whose causes were indetectable to conventional medicine – bodily pains, headaches, and even blindness.

Vannavuth could relate. He was born and raised in Cambodia to parents who lived through the Khmer Rouge and never left the country. As a college student, he interviewed families in villages to gain insight into why he and other Cambodians grew up amid poverty and suffering even if the genocide was over.

He quickly realized ways in which his own reality had been shaped by the trauma sustained by his parents. Keeping a mirror around to check whether attackers were coming from behind. Binge eating and hoarding food with the belief that being without food overnight would result in automatic death by starvation.

Vannavuth used his experiences to help treat a woman who had a ghost stalking her.

Dr. Sochanvimean “Vimean” Vannavuth, PhD, leading a Courageous Conversations workshop at UC Berkeley’s Southeast Asian Legacy Conference this year with Dorothy Chow, left.

Death in Cambodia, Life in America Podcast

“If you look at it from a Western perspective, they’re probably just going to see it as a hallucination. But taking it from my culture, ghosts could be real,” he said.

Vannavuth helped the patient confront the ghost to find out what it wanted and negotiate. They used puppets to act out the patient’s nightmares and memories, playing out alternative outcomes for seemingly doomed scenarios.

He was blending cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), Image Rehearsal Therapy (IRT), exposure therapy, lucid dreaming therapy, and hypnosis. These clinical methods, recommended for processing trauma and nightmares, guide the patient through triggering scenarios, replacing reactions learned in danger with incremental thought patterns rewired in safety. Gradually, the patient heals in emotions, thoughts, behaviors, and actions.

After over a year of intensive work, Vannavuth’s patient turned around one night to face the ghost on her own with the tools she had gathered. The ghost departed for good.

Vannavuth explained why trauma healing is so complex and can take so long.

For survivors of trauma, nightmares and night terrors often stem from actual memories. Being ambushed by these recollections during the vulnerability of sleep can easily trigger distress and result in re-traumatization.

The amygdala, an almond-shaped lobe of grey matter in the center of the brain base, processes emotional responses and traps stimuli collected during traumatizing events.

The amygdala, visible in Plate 718 of Gray’s Anatomy.

Anatomy of the Human Body (1918), Henry Gray

“If you experience intense pain, your brain’s going to try to cut off from it, otherwise you could literally die,” Vannavuth said.

This self-preserving compartmentalization happens at the expense of interactions with the frontal lobe of the brain that provides information-processing and reasoning capabilities.

To dismantle PTSD, a clinician must stimulate the amygdala while reconnecting its activities to the frontal lobe’s signals until a patient can emotionally distinguish the past from the present.

“The brain has to go through retelling the story over and over until it learns that, oh, I’m actually telling the story – it’s not dangerous,” said Vannavuth.

Patience and continuity are crucial; agitation without follow-through can result in regression.

Vannavuth said medications prescribed by psychiatrists to help balance brain chemicals can serve to disarm fear and anxiety just enough to enable the longer term “talk therapy” necessary to tackle the source of the symptoms.

According to a position paper by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, drugs psychiatrists currently prescribe for PTSD-induced nightmare disorder include serotonin-antagonist-and-reuptake-inhibitors (SSRIs) for depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder, anticonvulsive nerve pain medications, sedatives, hypnotic brain-slowing “benzos,” monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MOAI) antidepressants, antihistamines, hypotension-lowering alpha-1 blockers like prazosin, low doses of the cortisol stress hormone, tricyclic antidepressants, and atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia.

An accurate structural three dimensional representation of the prazosin molecule in the ball and stick model generated using Avogadro software.

Model by Wikimedia Commons user Myplanine

Vannavuth said that such prescriptions, not to be relied on as the sole aspect of treatment, must be written carefully by doctors who understand the full context and complexity of patients’ mental health challenges.

He remarked that he had yet to meet a psychiatrist of Cambodian/Khmer background.

From mass psychosis misdiagnoses to trauma healing

Over 25 years ago at Gardner Health Services, a behavioral clinic in San Jose, found that 160 out of nearly 200 Cambodian refugees had been administered with antipsychotic medication by well-meaning doctors from other facilities.

In 1999, Santa Clara County, on a quest to align its social security administration with its stated mission of cultural responsiveness, enabled the recruitment of Cambodian genocide survivor named Bophal Phen to the Gardner Health Services staff. At the time, Phen was a paraprofessional with a bachelor’s degree and no clinical license.

“I remember early on during my work here, I heard from a couple of clients talking about being 5150’d against their will,” said Phen.

“5150” is the number of the section of the state’s Welfare and Institutions Code that allows involuntary detainment of a person in a psychiatric hospital for up to 72 hours if they are gravely disabled or deemed to pose a threat to themselves or others.

Phen helped reevaluate the 160 cases of psychosis. None of the patients’ medical charts mentioned the genocide or its role in the psyches of patients exhibiting reactions to nightmares, sleep paralysis, and waking visions.

Cambodian refugee, mental health professional, and dedicated social worker Bophal Phen, LCSW, LAADC, at Gardner Health Services in San Jose.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Once the genocide and PTSD were included in the assessments, only four of the 160 patients were confirmed to be suffering from psychotic symptoms. The others had unaddressed PTSD, a contributor to high blood pressure, obesity, heart disease, and diabetes prevalent in the community, in addition to anxiety, depression, violence, gang activity, and addiction.

The practitioners before Phen had classified the Cambodian patients as “treatment-resistant.” Phen was committed to understanding, unraveling, and healing his community’s traumas and adapting new approaches from a place of direct experience.

As someone who was 10 when the Khmer Rouge uprooted his life back in Cambodia, Phen had thought for a long time that his own PTSD symptoms, including nightmares, were a fact of life. He had lived with bad dreams for as long as he could remember and now found himself responsible for helping others remove theirs.

He started by asking patients to talk about what was on their minds. “You tell me – you’re the expert,” they retorted.

The clinical convention of keeping professional distance was ineffective in these cases. Phen came to understand his patients by integrating into their lives – visiting them at their homes or driving them and their family members around to seemingly unrelated appointments and errands. Only after two years of this could clinical treatment really commence.

Several years into his job, he learned about acculturation, the consequences that can befall an entire community when it loses access to its own cultural resources. An antidote for this is reimmersion into culture, often made possible in places of faith where the community gathers.

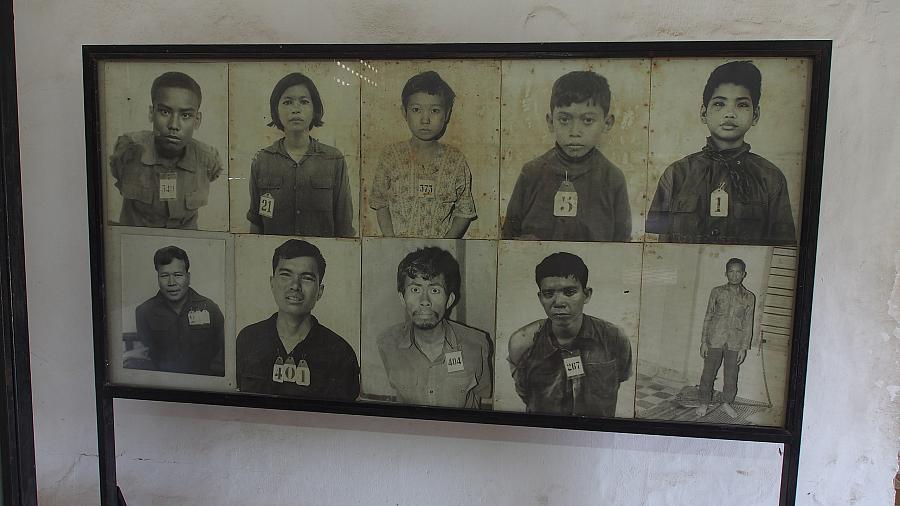

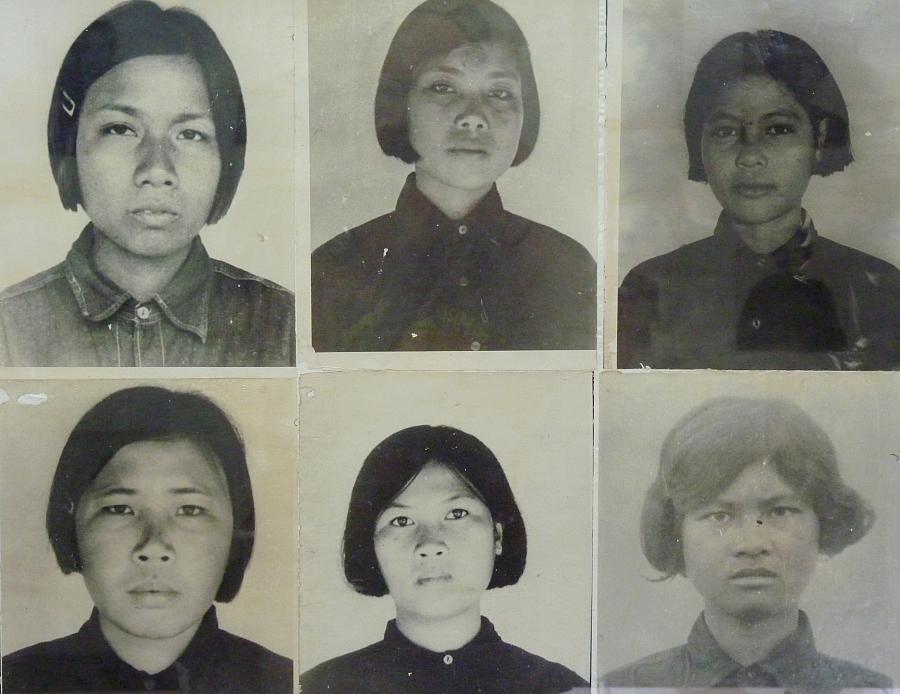

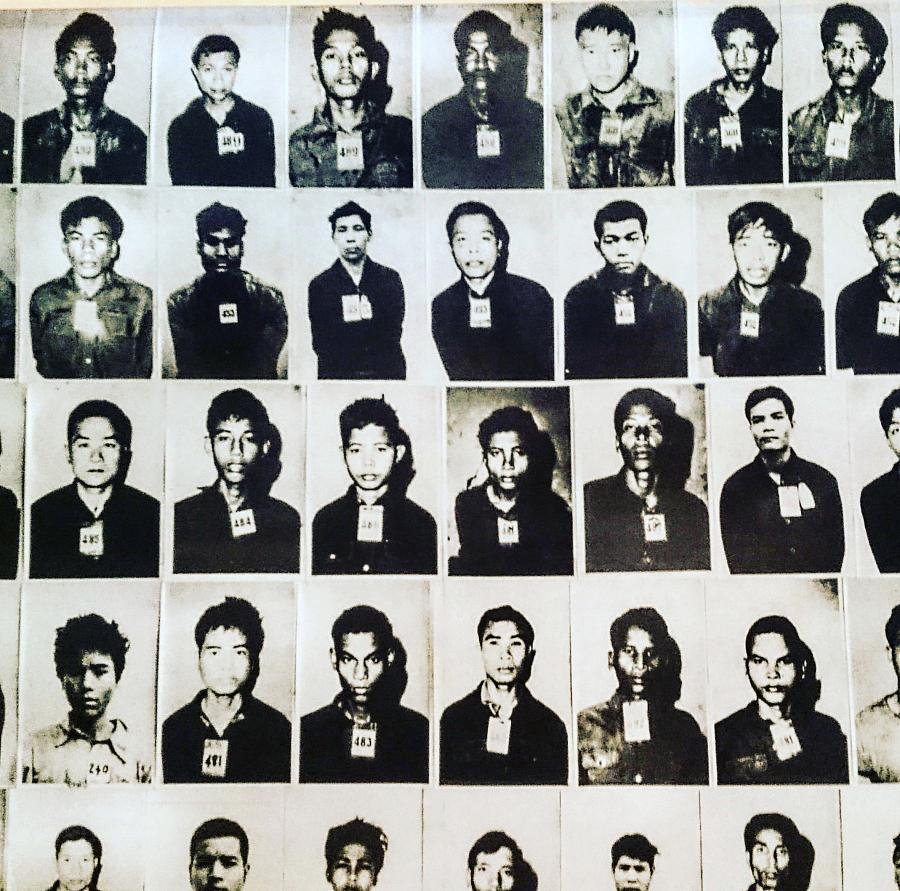

Victims of the Khmer Rouge genocide, depicted at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum and former S-21 prison site in Phnom Penh

He partnered with monks from temples to learn how to teach clients that they had agency despite their belief in karma, fate determined by previous lifetimes of events and actions. He also began taking the advice he gave to patients: breathe in, breathe out.

“Slowly, I healed myself,” he said. His nightmares have all but disappeared, though he can expect to have some after hearing other people’s stories.

Phen is now a licensed clinical social worker (LCSW) and Licensed Advanced Alcohol Drug Counselor (LAADC) working as a Mental Health Technician for what Gardner now calls the Ethnic Specific program.

He focuses on helping younger generations deconstruct their inherited trauma and heal.

The first generation of genocide survivors still come in by word of mouth, displaying any combination of the “mad, sad, and nervous” strains of PTSD, with nightmares to match. For them, direct, comprehensive, long-term in-language services are the only way out.

“You can’t do therapy with a translator,” Phen said, standing inside the room where he prefers to treat patients who visit the facility.

Children’s drawings and a radiant Buddhist altar adorn the sunny space, an oasis compared to the whitewashed maze of harshly-lit halls that lead to it.

Phen said this used to be where the original Cambodian team and its patients could be together as a community. But the pandemic and overall decline in services halted these gatherings until further notice.

Two Buddhist Monks in Cambodia.

Mark. J. Sebastian Photography/Alex Vo Films/Elevated Media

Phen hopes group therapy can return. He said the more Cambodians refugees age, the more they need to engage in wellness and socialization activities. These can include meditation and water blessings, which focus and calm the brain through trusted cultural practices carried out within the community.

But other than the hard-won project of the Wat Khmer Kampuchea Krom Buddhist temple expected to break ground next year, Phen knows of no formal cultural space in Santa Clara County where Cambodian/Khmer survivors and their families can find clinical services and culturally-based healing under one roof.

Supporting the journey from nightmares to dreams

Up in San Francisco, Sun’s research revolves around how to prevent the transmission of trauma from genocide survivors to the next generations. He emphasized the importance of catering each approach rather than conforming to the broadband binaries of Western or Eastern methods, of clinical and non-clinical modalities, or of talk therapy or drugs.

“It’s just not one size fits all. We cater,” he said. He wants to produce conferences where Cambodian/Khmer community members who work in mental health can compare notes.

According to the American Community Survey’s one-year estimates for 2023, 257,203 Cambodian/Khmer people live in the U.S. and 123,266 of them live in California. The Cambodian/Khmer mental health, research, and advocacy professionals in Santa Clara County serve a community that was 5,150 strong in the most recent 2021 ACS five-year estimates.

Raising awareness of and securing support for such a small subcommunity of the “AANHPI” racial/ethnic designation is a challenge, especially given a dearth of disaggregated data about these populations.

Diana Lam, LCWS, program supervisor at Gardner Health Services, said, “When it comes to the field of community mental health, the work that we used to be able to do isn’t the same as the work we can do now.”

The halls of Gardner Health Services in San Jose.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Years ago, California implemented a fee-for-service structure in its clinical facilities. Loren Gissible, LCSW, Gardner’s director of specialty behavioral health, told AsAmNews that the transition to the new structure, with its more complex billing codes, could have made the clinicians feel more restricted at first.

He said that, after working through a learning curve, the staff is still delivering the same care that they initiated in the 1990s. He added that Lam’s and Phen’s division is one of the highest producing in the organization.

However, the Cambodian team that once served over 100 Cambodian patients now works with 60 at most, divided between Phen and two Cambodian colleagues, with a full and half caseload.

The decrease is not necessarily because of a waning need for care.

As genocide survivors age out of Medi-Cal and into Medicare, many of them are enrolling in Medicare Advantage, a tier of senior health insurance with good medical reimbursements and cash incentives, in exchange for a higher share of costs of mental health services like those at Gardner.

“I don’t like that, if you ask me,” Phen said. “I like the good old days when anyone who needed services could get help.”

Gissible said that Gardner can work with low-income patients to reduce share of costs in certain situations.

Phen and Lam know that they can now triage inquiries through the Santa Clara County Call Center.

But Phen said, “Cambodians don’t call,” emphasizing that in-person contact is still the best way to reach elderly genocide survivors.

Gissible said that the call line is intended to be an additional resource for residents, and that Gardner and most organizations contracted with the county maintain an “open door” policy for requests for access to behavioral health services.

Finally, Lam worries that high costs of living in the area are endangering the pipeline of culturally responsive professionals who can do this labor-intensive work.

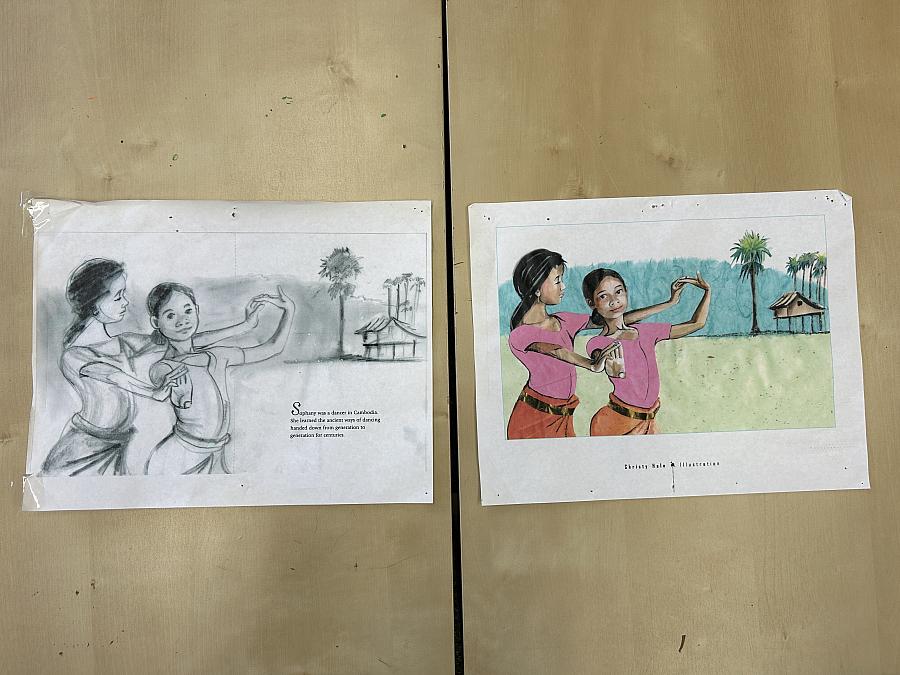

Sketch and illustration in a children’s book authored by one of the original members of the Cambodian Team at Gardner Health Services.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

But she and Phen aren’t thinking of going anywhere.

“Our Asian team, the Cambodian team especially – nobody wants to leave. You see the change in people and it’s like you have another member of your extended family,” Phen said.

Sun, just a couple of counties away, urges his generation of Cambodian/Khmer survivors and their descendants everywhere to remember that from great pressure comes diamonds.

And perhaps from nightmares, dreams.

This project is supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.