‘Horrifying’ wait times for state hospital beds, official says

This project was produced as a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2021 National Fellowship.

Other stories by David Barer and Josh Hinkle include:

Austin court’s redirection of those committing low-level crimes could be saving taxpayer money

Jail waitlist for mental health help hits new record. This plan proposes a statewide fix.

Mental competency consequences: the hidden, unreliable data Texas tracks… or doesn’t

Wrong races, hidden names among data challenges our team faced with jail mental health project

Mental Competency Consequences: The Hidden and Unreliable Data Texas Tracks — Or Doesn't

State of Texas: Leaders consider ‘consequences’ of not tracking state hospital waitlist data

State mental hospital backlog grows, new record exceeds 2,500 waiting in jail

A state hospital death in restraints and seclusion: What happened to Justin Reeder?

Despite waitlist record, leaders keep pushing ‘Eliminate the Wait’ plan for state hospitals

Thousands waiting in jail for state hospital beds, is help coming?

AUSTIN (KXAN) — When State Sen. Sarah Eckhardt thinks of the state hospital waitlist, she remembers a constituent she learned about who had a mental health crisis. The man had no criminal history. His neighbors called for help expecting him to be taken to a mental health facility. Instead, he was booked in a county jail, stripped naked and put in a rubber room. There he waited, until a scarce bed in a state hospital opened, she said.

Eckhardt called that outcome “tragic.” State data show a record number of people experiencing a mental health crisis are waiting in jails for beds in state hospitals that don’t have enough staff to operate at capacity.

The state hospital waitlist problem has been building for years. In March, there were a record 2,309 people waiting in jail for a bed, another record high.

Under normal circumstances, a person charged with a crime and found mentally incompetent to stand trial would be quickly sent to a state hospital for mental competency restoration. Once stabilized, they could return to jail and proceed with their case. Without room in the state hospitals, these people now languish in jail, in many cases more than a year. That leaves their families and others waiting for closure, too.

“Every day I walk into (the Capitol), I’m confronted with yet another example of us reacting to a perpetual crisis, rather than actually governing – whether it’s the grid, whether it’s public education, and in this case, it’s mental health care and its nexus with public safety,” said Eckhardt, an Austin Democrat.

Last November, the number of individuals waiting for a state hospital bed – 1,933 – exceeded the total number of available beds – 1,510 – for the first time, according to HHSC data. That gap has since widened.

Eckhardt said there’s no “silver bullet” to fix the situation. But, solving the problem, she said, is not “rocket science.”

“We know what the solutions are: workforce, expanded Medicaid, and a diversion out of jail circumstance and into a doctor’s office,” she said. “Currently this crisis management is ineffective. It’s inefficient. It’s unfair, and it’s exceedingly intrusive on the individual who is suffering.”

EXTENDED VIDEO: KXAN’s Josh Hinkle interviews Sen. Sarah Eckhardt, D-Austin, about her plans to address mental competency challenges in Texas.‘True public health emergency‘

Windy Johnson, a member of the Joint Committee on Access and Forensic Services, called the waitlist situation “horrifying” at the committee’s April 20 meeting. That group monitors the waitlist, collects data and provides guidance to HHSC.

“I feel like this is a real true public health emergency, and it’s not being treated like that,” said Johnson, who represents the Texas Conference of Urban Counties. “I can’t imagine, you know, another year just hoping to get increased legislative funding to address 2,400 people sitting in jail for almost over a year.”

Not only has the state hospital system lost 4,000 workers over the past two years, but monthly job applications have also dropped significantly, HHSC Deputy Executive Commissioner Scott Schalchlin said at the April meeting. The state hospital system was averaging 15,000 applications per month, but that dropped to about 5,000, he said.

Johnson asked the committee if the National Guard had been called in to provide relief for staffing issues. Johnson’s call for military resources echoed similar remarks made in January by committee member Jim Allison, general counsel for the County Judges and Commissioners Association of Texas.

GOING IN-DEPTH

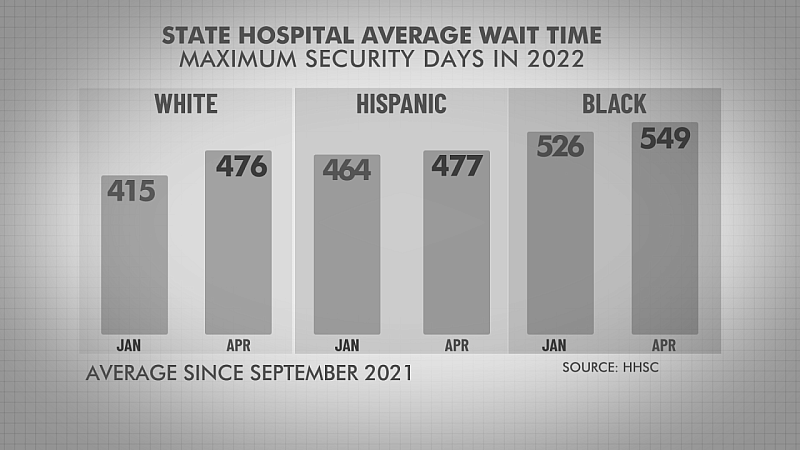

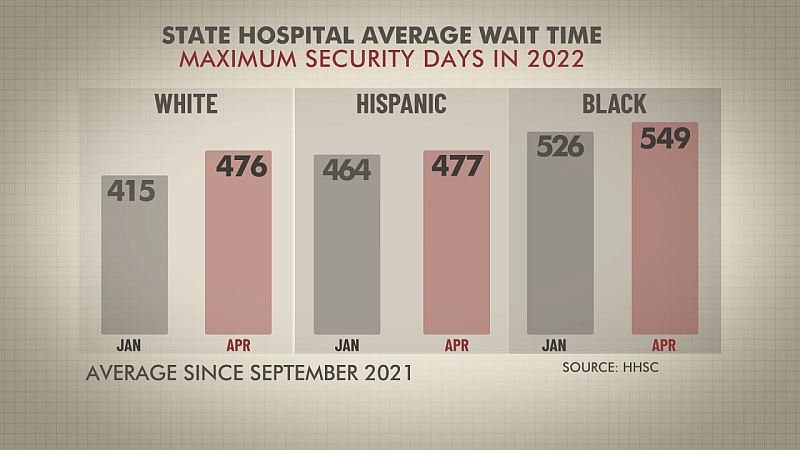

The waitlist is divided into two parts: maximum security and non-maximum. As the waitlist has grown, so has the average wait time. In March, people waited an average of 538 days for a maximum-security bed and 261 days for a non-maximum security bed.

Scott Schalchlin, an HHSC deputy executive commissioner over the state hospital system, said it is not usually the National Guard’s mission to assist with an open-ended staffing situation like the state hospital’s. Schalchlin said the workforce issues have been elevated to the highest levels of state government. Gov. Greg Abbott’s office has been “supportive” of HHSC’s current approach, which is to increase staff by streamlining the application and hiring process and publicizing hiring bonuses of up to $5,000 for certain positions, Schalchlin said.

The changes may be helping.

The state hospital system saw a 40% jump in applications from February to March, the largest increase since the pandemic began, Schalchin said.

The hiring bonuses have been “hit or miss,” Schalchlin added. Some people have earned the bonus and left “once they hit a certain number of months with us.”

Aside from improving the workforce, Eckhardt said the state should collect better data to identify solutions and high-performing local mental health programs, she said.

Krishnaveni Gundu, co-founder and executive director of the nonprofit Texas Jail Project, said funding and state beds aren’t the only solutions. More work should be done by counties to provide “community based healthcare, housing, crisis respite units, rehab and other evidence-based solutions that can address the problem at the front door.”

“Most county budgets are heavily skewed toward carceral solutions. We get what we pay for,” said Gundu.

Last year, KXAN investigated HHSC’s data collection effort and found gaps in the state’s work. Many details that experts say are critical aren’t tracked. For example, the state doesn’t keep data on the number of people on the waitlist who are experiencing homelessness or can’t afford an attorney. The state also doesn’t keep track of people that die while waiting for a state hospital bed. HHSC said it still isn’t tracking that information.

In January, for the first time, HHSC publicly displayed a racial breakdown of people on the waitlist. HHSC released a second batch of racial data in April. Both datasets showed a disparity between Black and white people’s wait times for maximum-security beds.

White people wait a shorter amount of time, on average, than Hispanic or Black people for a state hospital bed, according to fiscal-year-to-date state data.

Anomaly?

Data released in January showed Black people were waiting, on average, 110 days longer than white people for a maximum-security bed.

When KXAN asked HHSC why that disparity existed and what the agency was doing to better understand it, an HHSC spokesperson said it was “an anomaly.”

“Although the data show that during this time, Black or African-American people had a longer average wait time, this appears to be an anomaly as race/ethnicity data outside of this time period suggests there is no consistent pattern of any particular race/ethnic group waiting longer for admission over others,” HHSC chief press officer Christine Mann said in an email.

Three months later, the trend continued.

Fiscal-year-to-date data from April shows Black people waited an average of 73 days longer for a maximum-security bed than whites.

HHSC said the wait times in the public data are a snapshot of the fiscal year to date, which began in September 2021. Examining the data by month shows more variation in average wait times, including some individual months with average waits for white people being longer than Black people.

A number of variables could affect how long a person waits for a state hospital bed. For example, a person could be on a medical hold for a condition that cannot be treated in a state hospital, or they could have specialized programming needs. There are also state laws that require certain people be admitted within certain timeframes, according to HHSC.

The agency said it “will continue to monitor our wait list data to ensure that any racial or other disparities are identified and addressed as soon as possible.”

Sen. Sarah Eckhardt sits in her Capitol office for an interview with KXAN's Josh Hinkle about the waitlist.

Eckhardt, a former county judge who has studied the waitlist issue and proposed legislation in 2021 to improve state oversight, said the racial disparity was “unfortunately unsurprising, when you look at the incarceration data on through racial demography.”

“African Americans are much more likely to be taken to jail for a mental health crisis than a person of another race,” Eckhardt said. “It is laughable to think that that is an anomaly, when you look at the statistics in criminal justice over decades.”

Moving forward, Joint Committee on Access and Forensic Services member Stephen Glazier said he and other members are working to provide the committee with waitlist and wait time data sorted by every county in the state.

“Our goal for this committee right now is to keep analyzing the data to see what it tells us in terms of hopefully we will be able to have some data driven recommendations for policy actions or legislative action,” Glazier said in April.

The story is part of the KXAN investigation, “Mental Competency Consequences,” a project supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

[This story was originally published by KXAN.]