Housing costs cramp business in expensive communities

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Courtney Teague, a participant in the 2019 California Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Pricey housing in Napa County can cost more than your paycheck. It can affect your health

Napa Valley strangers talk housing struggles over a pizza party

Local officials to discuss housing, take public questions at Register town hall

Renter’s handbook: Here’s how to navigate the top 6 tenant housing issues

Farmworkers, the backbone of Napa Valley's economy, face health challenges

Tim Carl

Editor’s note: This article is part of an occasional series that takes a look at how Napa County’s high housing costs affect local residents and workers. Read the first story in the series here. RSVP for the Register’s town hall and resources fair on housing here.

Lissa Doumani, half of the chef-owner duo who operated St. Helena restaurant Terra for 30 years, learned the hard way that steady business and loyal customers aren’t enough to last in the Napa Valley.

Businesses need workers. And workers need housing.

Doumani said she and her husband, co-owner Hiro Sone, spent as much time trying to hire staff for their Michelin-starred restaurant as they did finding housing for those potential workers. Some employees drove to work from less costly communities such as Fairfield, Vacaville or Sonoma County — unpleasant commutes for tired workers just getting off a shift, she said.

Business owners say long commutes can weigh on workers. Studies link commuting and stress.

Housing woes were a frequent topic of conversation among staff and business owners, too. Everyone needed workers, but there were so few places for them to stay.

“It was the only topic of conversation,” Doumani said. “We didn’t ask how business was … ‘What are you doing for people? Where are you finding them?’”

Housing troubles were part of the reason that Doumani and Sone decided the doors of St. Helena restaurant Terra would close in June 2018, during peak season for visitors.

Terra was short-staffed toward the end of its run. Things began to get harder after the 2017 wildfires that hit northern Napa County, when rents increased and the housing stock shrank.

Local employers say the cost of living is an impediment to recruiting workers. Some complain of ever-increasing rents at their storefronts, and say they struggle to offer employees benefits and comfortable wages, forcing some to take extra jobs or move to a cheaper community.

Despite a lack of affordable housing, visitor attractions continue to pop up in Napa County and bring jobs to the area. Napa Mayor Jill Techel said last year that new hotels would have to have a plan to address housing for their workforces.

The Napa Valley Wine Train, a popular tourism attraction that offers dining and recreational train rides, announced plans to build a new hotel and rail station earlier this year. They later went public with plans to build two apartment buildings, for a total of 55 units to house employees with Wine Train and a proposed Wine Train hotel.

“We can’t attract the right employees unless we offer some sort of affordable housing option,” said Jamie Colee, president of development at Noble House Hotels, which co-owns the Wine Train.

Naomi Chamblin, owner of bookstore Napa Bookmine in downtown Napa, said she’s fortunate that her staff have below-market-rate housing or live with family. She does, however, see customers come and go because of the cost of living.

Most of Bookmine’s employees are part-time, she said. Chamblain said she wishes she could pay $20 per hour, but isn’t able to do so. Some staff work second jobs in hospitality, where they get tips and are better-equipped to afford life in Napa.

“We have a really amazing staff who we want to pay more than the living wage,” she said. “We want them to thrive here.”

Commuting causes stress, fatigue

The Register has heard from roughly 200 people who shared the sacrifices they have made to work or live in Napa County, as part of a collaboration with the University of Southern California’s Center for Health Journalism. Many complained about traffic associated with out-of-county commuters coming to work in the area, including some locals who said they left Napa County for a less expensive community.

Researchers have found commutes can be hard on the body and mind.

A commute of even 10 miles has been associated with high blood pressure, according to a 2012 study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine. That’s the distance between Napa and American Canyon, the most affordable city in Napa County.

Researchers noted commuters were stressed, slept poorly and missed more work due to illness in a 2011 study of Swedish workers, published in BioMed Central Public Health.

A 2015 survey of Norwegian workers found that people who faced long commutes for more than 10 years “reported more gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal complaints than those with long commutes for less than 2 years,” according to a study published in Preventive Medicine Reports.

Some researchers claim the stress of commuting is so great that it outweighs benefits such as taking a more desirable or better-paying job, or living in a preferred community.

The housing supply in the San Francisco Bay Area, which includes Napa County, hasn’t kept up with demand, said Elizabeth Kneebone, research director for University of California Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation.

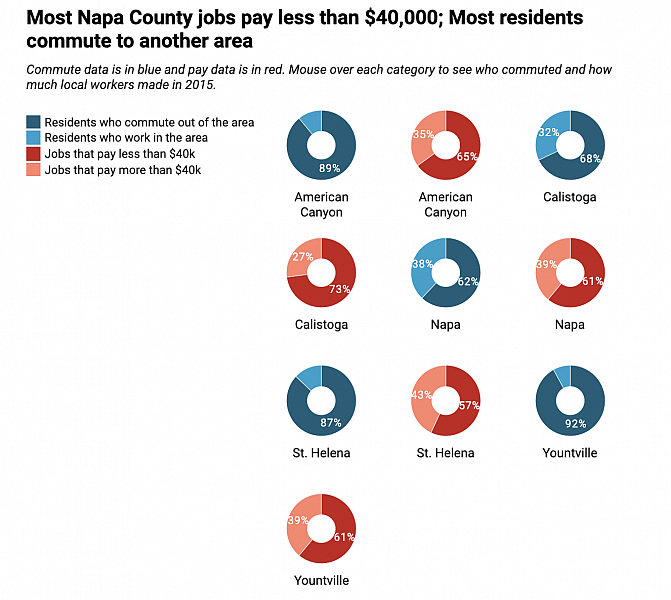

See how many Napa County residents commute by interacting with the graphic below

American Canyon workers face a median commute of 14 miles, according to a Terner Center dataset that pulls from 2015 U.S. Census Bureau statistics. That’s a longer commute than the Bay Area median, Kneebone said.

The Census Bureau also tracks the share of local jobs that are held by local workers. In American Canyon, 11 percent of workers also live in the city.

The median commute for Napa workers is nearly 11 miles, data shows. Four in 10 Napa workers live in the city.

St. Helena workers face a median commute of 17 miles and just one in 10 workers live in the city, data shows. Calistoga workers commute 11 miles and about a third of workers live there, too.

Yountville workers have the shortest median commute at nine miles. Just eight percent of workers there also live in Yountville.

Workers may struggle to live in or near the community where their job is, which means more time sitting in traffic and money spent on transportation, Kneebone said.

Napa County isn’t the only place that loses residents to less expensive communities. Kneebone and her colleague at the Terner Center, Issi Romem, released a study in 2018 that looked into who leaves the Bay Area.

“Those moving into the Bay Area are substantially more affluent and educated than those leaving,” they wrote.

Low-income black and Hispanic residents comprise a disproportionate number of the people who leave the Bay Area, the study found. When they leave, they tend to go to more affordable parts of the state.

If workers must leave their communities, Kneebone said losing relationships built over time is even harder than finding a new job. Neighbors and members of a faith community may offer each other moral support and a financial cushion for times when money is tight in between paychecks.

Alexis Handelman, owner of Alexis Baking Company café in downtown Napa, said most of her staff live within a 20-mile radius, but even that can mean a hefty commute. Some of her staff have commuted as far as Fairfield or Cordelia, which can be up to an hour away with traffic. Handelman said she once hired a woman who lived a four-hour drive away in Eureka, but that didn’t last long.

Traffic can take a physical and emotional toll on staff, zap their energy levels and leave them frazzled, she said. Hours spent in traffic makes kitchen staff more vulnerable to accidents involving hot liquids, knives or slippery floors.

A lack of local, affordable housing complicates things for businesses, too.

“Everybody needs workers,” she said. “How do you attract really good people if there’s no place for them to live?”

Customers have high expectations that workers can’t always meet. It’s not uncommon for staff to show up to work, drained from a late-night shift at a second job or an hour-long commute from a cheaper city, she said. Handelman said she recently hired a man who leaves his job at a local restaurant at 11:30 p.m., then comes to work at her bakery at 6 a.m.

“I send them out on the floor to be nice to people and the last thing they want to do is be nice,” Handelman said.

Napa County visitors spent $2 billion in 2018. Hotel guests spent an average of $445 per person, per day, according to tourism marketing group Visit Napa Valley. At the swanky Andaz Napa hotel in downtown Napa, guests may spend $400 per night for a single-bed room.

Alexis Baking Company workers, just two blocks away, might earn enough to afford that room after three full work days. The average employee makes $15 per hour, Handelman said.

Many local workers say vacations like this are out of reach because of housing expenses. The county estimates that one in three households are cost-burdened, or spend a third of their income on housing.

Housing isn’t employers’ only struggle

For some small business owners such as Chamblin of Napa Bookmine, offering health insurance is “absolutely an impossibility … it’s not really a decision.”

Some of Chamblin’s staff are among the 7% of Napa County residents who are uninsured, according to 2017 Census estimates. That weighs on her.

In the long-term, she hopes Bookmine can provide coverage to employees. There’s talk that the American Booksellers Association will offer a health care program and that could be Bookmine’s best bet, Chamblin said.

“We care about our employees,” she said. “We’re a small family at this point … You want your people to be protected.”

Booksellers are in a unique position, Chamblin said. While bookworms tend to find the work fulfilling, sellers can only bring in so much money. Book prices are fixed because they’re printed on the back, she said, and sellers don’t get tips.

Like some other downtown Napa businesses, Chamblin must also find a way to meet ballooning rent costs. Her landlord raised the rent for her Pearl Street bookstore by 70 percent in June, which meant Bookmine needed to increase business by 20 percent to survive the new rent costs. Chamberlain and her husband, co-owner Eric Hagyard, took to social media to plead for their customers’ support.

“I was freaking out,” she said.

Bookmine was already gearing up to buy its own space in 2020 to avoid sporadic rent increases.

In their new location, she said, Bookmine “won’t have to fight rent that’s growing much faster than our business can.”

Much like Bookmine, many local residents must grapple with costly rents that hurt their bottom line. Nearly four in 10 Napa County residents rent and half of renters are housing-cost burdened, meaning they spend at least a third of their income on rent, according to 2017 Census estimates.

In spite of the difficulties that workers face in making ends meet, Handelman of Alexis Baking Company said it’s inspiring to see the strength and resilience of those fighting the housing crisis — particularly those who meet the heavy demands of juggling jobs.

But Handelman sees the fatigue in her own staff. Affording life in the North Bay isn’t easy.

And she’s convinced that the hustle will eventually wear on those workers.

“We’re asking people to be kind of superhuman,” Handelman said. “Everybody needs to be an actor.”

Courtney Teague reported this story as part of her University of Southern California Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2019 California Fellowship. The Center’s Interim Engagement Editor Danielle Fox contributed engagement support to this article.

[This article was originally published by the Napa Valley Register.]