How do we treat L.A.’s overwhelmed emergency medicine system?

The story was originally published in AfroLA with support from our 2023 Data Fellowship.

Illustration by Hal Marie Saga

On a recent call, EMT Adrian Galvan transported a patient who complained of being short of breath and COVID-19 symptoms. The patient couldn’t stand on his own and needed oxygen to breathe. Galvan, who works for private ambulance company McCormick, took the patient to Lakewood Regional. The ER was so crowded when they arrived, Galvan and his patient waited nine hours. Once the patient was discharged from the gurney, they spent another hour waiting to be admitted to the ER.

Overcrowded hospitals can cause delays that force EMTs to sit with their patients in ambulances. “We went through multiple [tanks] of oxygen–like the big canisters, seven of them,” Galvan said.

Galvan’s supervisor came to the ER to speak to hospital staff directly. Galvan said the hospital insisted they didn’t have a bed, but he later learned a bed had been available 30 minutes after that patient arrived at the hospital.

Research into the causes of long ER wait times for patients arriving by ambulance, and solutions to the problem have been slow, if non-existent, according to David Tan, emergency department division chief at Washington University in St. Louis:

“The underlying root of the problem has not changed. So, nobody feels the need to update research when the original problem remains, which is not emergency department overcrowding, but more honestly, hospital overcrowding. ERs cannot get patients out of the back and upstairs to inpatient services, which makes getting patients through the front door of the ER next to impossible. Many ERs are on ‘disaster’ status as a matter of routine which is why so many go on ‘diversion.’ Hospitals have no incentive to rapidly discharge patients who are ready to go, clean rooms, and get patients up from the ER as soon as possible. So, it ‘becomes’ an ER problem.”

The “ER problem” is much more prevalent in South Los Angeles. Hospitals here, serving predominantly Blacks and Latines, are more likely to go on diversion – where ambulances are forced to go to another hospital when one hospital is overcrowded – and are more likely to be under-resourced or understaffed.

How diversions and long wait times happen

Inaccessible primary care and preventive health services mean that many people turn to hospital ERs for medical attention, even when the care they need is more in line with what an urgent care or a primary care physician could provide. Consequently, reports the the California Hospital Association, emergency departments are overwhelmed and oversaturated. Hospitals handling too many patients directly cause EMTs and their patients in incoming ambulances to wait longer for an emergency bed.

The intent with these policies is to process EMS patients at receiving facilities as soon as possible in order to release the EMS resources back into the community to be available to respond to 911 calls. Sometimes, however, the system just gets overloaded, and we get stuck holding the wall.

Glendale Fire Department Battalion Chief Todd Tucker

Ambulance diversion happens when an ER that is severely overcrowded or understaffed must close to new emergency patients in order to manage the patients they already have. Hospitals with a diversion status must reroute any incoming ambulances to another hospital.

Delays caused by diversion and long wait times are commonplace, and can lead to serious injury or even death, as was the case for Ryo Miyasaka’s family.

Miyasaka and his parents often woke in the middle of the night to take his older brother with Lou Gehrig’s Disease to the hospital. They sat huddled in the ambulance into the early hours of the morning, waiting for an emergency room bed to open. Prolonged delays like these can be deadly. “…[My brother] was on a bed with the ventilator, you know, running on oxygen for like 16 hours. For a critical care patient on a gurney, like, he has no ability to really communicate except his eyes [the whole time]. That’s just—to me, it was horrible,” Miyasaka said.

A McCormick ambulance pulls into the ambulance bay of Centinela Hospital in Inglewood.

Richard Grant/AfroLA

Miyasaka was 18 when his brother, Hajime, died at age 23. Miyasaka, now 26 and an EMT for McCormick, said he chose his career because he wanted to be there for kids like himself and his brother, affected by long ambulance wait times.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, wait times ballooned to 10 hours in L.A. County. In 2022, the average wait time in a California ER was about 3.5 hours for serious cases, according to data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Hospital emergency departments’ response to more patients than health care providers can treat is to cut off one source of incoming patients: ambulances.

In 2015, the state of California directed state EMS agencies to create a common definition of ambulance patient offload times and create a standard for decreasing wait times.

Per county guidelines and a recent audit report, all diversions must be communicated through the interhospital ReddiNet system, and each hospital should maintain its own policy and requirements for diversion. In general, diversion can be enacted if hospitals are overcrowded or there are not enough staff or resources to treat a patient.

Before an ambulance can be “diverted,” said Miyasaka, “It is the responsibility of L.A. County Fire dispatchers and hospital administration to figure out an alternative hospital that can take the patient. Sometimes, the hospital L.A. Fire chooses is even more impacted by hospital overcrowding than the original hospital,” said Miyasaka. This means he often has to care for severely injured patients himself.

“If the EMTs are still waiting with the patient at the hospital for a bed to open up…and something bad happens to the patient, EMTs will still care for the person until they are able to safely hand them over to hospital staff,” Glendale Fire Battalion Chief Todd Tucker told AfroLA.

Many ERs routinely operate over capacity, meaning there are more incoming people than licensed beds to accommodate them. EMTs are often left waiting with their patient for a bed to open up, what they call “holding the wall.”

Glendale Fire Department Battalion Chief Todd Tucker stands at the garage door of the Station 21.

Richard Grant/AfroLA

In 2020, California hospitals’ emergency rooms were closed about 6% of the time. From 2021 to 2023, state ERs’ closures to incoming ambulances increased 50%.

Regulations mandate that registered nurses in emergency rooms care for no more than four patients at a time. When RNs reach their four-patient maximum and there are still critical care patients coming in and lower-triaged patients waiting with EMTs, it’s chaos.

“It's not the nurses’ fault. It's the hospital's fault for not having more resources there because the hospital administration never wants to close the hospital. If the administration closes [the ER] too many times in a year, they lose funding because closing it means they’re overrun, that they aren’t prepared for more emergencies,” EMT Katrina Slye said. Slye was an EMT with McCormick, one of the private ambulance companies contracted by Los Angeles County, for five years. She quit last year, she said, due to frequent 72-hour shifts and comparatively low pay which left her scrambling to pay bills.

“If you're holding a wall with somebody, and somebody [else] comes in that was shot, they [nurses] have to take care of that. And then if there's somebody else that codes, they have to take care of that,” said Slye.

Ambulance Patient Offload Time, known as APOT, is the time between a patient’s arrival outside emergency department doors, where they’ll be unloaded, and the time that patient is transferred to the emergency department. Patients may be moved to a gurney, bed, chair or other licensed location. At the hospital, fire paramedics and EMTs relinquish control of patient care by handing over a care report detailing where the patient is coming from, their injury or complaint, demographic information, and the time that they were handed over to the hospital.

“They're waiting to offload their car and they're just sitting there basically waiting for triage to tell them, ‘Hey, you can put your patient on this bed.’ You would think that you go to the hospital and then go right away [to a hospital bed because that’s what you see on TV]. It doesn't really work like that,” said Miyasaka.

Disproportionate impact on communities of color

Overcrowded hospitals that are on diversion status more often tend to have longer ambulance patient offload time. South Los Angeles residents, predominantly Black and Latine, are disproportionately impacted by long offload times.

Centinela, Inglewood’s only hospital, averages 16,000 hospital visits and 56,000 ER visits per year. Here, it takes around an hour for EMTs to offload patients into emergency hospital staff’s care. This offload time is 30 minutes higher than the county standard.

An Inglewood woman (who asked her name not be published to protect her medical privacy) told AfroLA she purposefully doesn’t go to Centinela, the “rundown ER which is close to [her] apartment.” She has severe asthma and other respiratory issues. She said she prefers another medical center farther away because Centinela doesn't have the proper resources to care for her condition. And, she’s not been believed about how much pain she’s experiencing.

McCormick ambulances wait outside the emergency room of Centinela Hospital.

Richard Grant/AfroLA

EMTs who work out of South Los Angeles stations interviewed by AfroLA said their patients are often diverted to Lakewood Regional, southeast of Compton, and St. Francis Medical Center in Lynwood. These hospitals serve significantly more patients than others in the area. Their offload times are some of the worst in the county. On average, offloading patients at Lakewood takes 83 minutes and nearly 90 minutes at St. Francis.

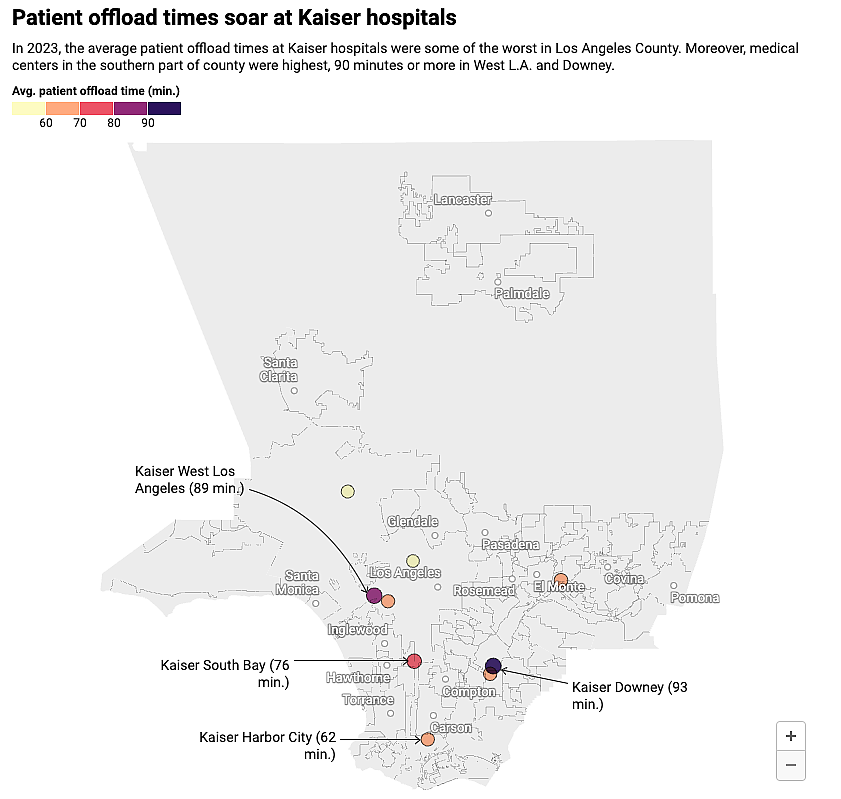

Offload times at Kaiser hospitals are also dismal. There are eight Kaiser hospitals with emergency or urgent care services in L.A. County. Unlike most hospitals, Kaiser only takes insurance for their members, and contracts with Medicare and Medi-Cal. Members can be any age or income with any health condition. Their offload times are some of the worst in the county. All Los Angeles Kaiser hospitals average at least an hour for offloading patients from EMTs to ER staff. Offload times at Kaiser Downey average more than 90 minutes, the longest of the Kaiser hospitals.

The state and Los Angeles County offload time standards both call for a patient to be transferred from an EMT or paramedic’s gurney to hospital care within 30 minutes. The goal is for this to happen 90% of the time.

But, that’s not the reality.

Sixteen percent of the state’s hospitals have average wait times longer than 30 minutes. No data is available for L.A. County. Some EMS agencies – both private and county-owned – operating in L.A. County submitted data to the state while others did not, for unclear reasons. Los Angeles County Fire administrators told AfroLA that McCormick, Falck and AMR ambulance, the three main private ambulance companies contracted by the county for 911 calls, had been sending offload data to the state EMS agency for some time, but other agencies, like L.A. City Fire was not. The state may not have wanted incomplete data for the County. In 2019, the state asked for $189,000, and $149,000 each subsequent year, to investigate ambulance offload times. In fiscal year 2023-24, the state EMS agency requested $4.9 million to continue funding their operations, including monitoring ambulance offload times.

“The intent with these policies is to process EMS patients at receiving facilities as soon as possible in order to release the EMS resources back into the community to be available to respond to 911 calls. Sometimes, however, the system just gets overloaded, and we get stuck holding the wall,” said Glendale’s Chief Tucker.

Glendale Fire is a standalone agency that’s not part of L.A. County’s EMS system. Glendale paramedics all work for the city and only transport patients to the four hospitals within the city. Here, average wait times are much lower than in L.A. County, between 20 and 40 minutes on average. Tucker attributes this to fewer calls and monthly meetings dedicated to analyzing response times and resource management.

Paramedics stationed at Glendale Fire Department's Station 21 depart from the engine bay to run a training drill on March 1, 2024.

Richard Grant/AfroLA

At the conclusion of every month, Tucker, other Glendale fire department personnel, and hospital nurses and administrators gather to review offload data. In addition to assessing average wait times and discussing steps for improvement, it’s also a chance for a post-mortem on specific cases.Tucker said he tracks tough or unusual cases transported to hospitals to monitor outcomes and each case’s wait time. If it exceeds 40 minutes, he adds the case to the monthly meeting’s review pool.

When ambulances must wait for a bed to open up for their patient, it is a matter of leveraging relationships with hospital staff to ensure patients receive the care they need.

"Hey, what can we do to start clearing the most serious patients off these gurneys and have them get their care [transferred to the care of] hospital staff?” said Tucker. “Tying up ambulances and fire paramedics at hospitals puts the rest of the community at risk, because, now, they can no longer answer emergency calls.”

Saint Francis Medical Center in Lynwood.

Photo Courtesy of Clayton Kazan / via Google Images

The impact of hospital closures on ER care

In 2021, visits to California ERs increased 7%, according to California Health Care Foundation data. That year, roughly one-third of Los Angeles County’s 9 million residents visited the ER at least once. The number of visits classified as "severe with threat" increased 68% in the decade between 2011 and 2021.

Long wait times without an emergency room bed or care from hospital staff can lead to delays in care, and even death. For under-resourced hospitals, this can mean closures, said Tucker. Closures of maternal health wards and trauma wards are caused when a hospital no longer has the resources or the staff to maintain that part of the hospital. A high volume of patients with increased wait times and care delays are a sign that a hospital may not be able to sustain their services.

A closure of an emergency department in an area doesn’t mean that everyone in the area stops having heart attacks or strokes, or cutting their fingers off. It means that they will be transported to the next emergency department, which may be more crowded because now, it sees patients from two areas instead of one.

Renee Hsia, vice chair for health services research at the UC San Francisco emergency services department

In the pandemic’s wake, one in five hospitals across the state were at risk of closing in 2022. As costs to maintain care rise, they face a budget crisis that is increasingly “impossible to balance,” according to a recent report from the California Hospital Association. California hospitals lost $8.5 billion from 2019 to 2022.

“In school, when we do our ride-alongs, we’re told we’re gonna be stuck in the ER triage area for hours and hours,” said Miyasaka. “We’re taught that’s the ‘norm.’” Miyasaka explained he understands the impacts of this firsthand.

Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital is located in the Willowbrook neighborhood just south of Watts. When “Killer King,” as it was dubbed by locals, closed inpatient and emergency services in August 2007, St. Francis became the closest Level I trauma center for Miyasaka at his Willowbrook fire station. (A new MLK hospital facility opened next to the old building in 2015.)

Level I trauma centers, which have the most extensive resources available to treat critical injuries, are inherently busy. So, when they’re overcrowded, there can be dire consequences.

Slye recalled an incident during her time as a McCormick EMT. “There was this one time at St. Francis when our paramedic was holding the wall with a patient who was having a heart attack. It came up as a STEMI [a severe heart attack caused by complete blockage of the coronary artery] on his monitor, which is why [the paramedic brought the patient to the hospital in the first place], and he was holding the wall for like 40 minutes. He [the paramedic] was like, ‘This is insane. Like, heart tissue is dying and we're holding the wall.’”

McCormick EMTs Ryo Miyasaka (left) and Adrian Galvan.

Courtesy Ryo Miyasaka

Heart attack patients are often waiting for beds at under-resourced and understaffed hospitals, Slye said, because patients with more severe wounds, like gunshots, need to be triaged first.

A 2016 study on the effects of MLK’s closure found that trauma admissions, especially gunshot wounds, increased at three of the four nearby hospitals. In the two years following MLK’s closure, researchers reported gunshot wound mortality increased from 5% to nearly 8%. And, surrounding hospitals saw a surge in uninsured patients.

The color of care

Recent closures of emergency departments, trauma centers and maternal health wards in Los Angeles County have resulted in significant increases in remaining ERs’ wait times and number of patients, and a decrease in the quality of care, said EMT Miyasaka.

According to 2012 research from UC San Francisco, crowding in a hospital serving Black or Latine communities may indicate a fundamental mismatch between supply, what resources are available to a hospital, and demand, the urgency of the public’s need for resources, in those areas.

“A closure of an emergency department in an area doesn’t mean that everyone in the area stops having heart attacks or strokes, or cutting their fingers off. It means that they will be transported to the next emergency department, which may be more crowded because now, it sees patients from two areas instead of one,” said Renee Hsia, vice chair for health services research at the UCSF emergency services department.

Staffing and resource shortages, hospital overcrowding and time “holding the wall” for emergency department beds are seen more often in predominantly Black and Latine communities. The quality of care can also differ for people of color.

Miyasaka said he sees and hears his colleagues be more negative toward patients who live in lower-income areas. While working for another private ambulance company, Miyasaka said he witnessed paramedics with a completely different attitude on a call to Malibu. He attributed their more attentive care to the area’s affluence. He said hospital wait times in Malibu were much shorter than in Los Angeles, 10-20 minutes at the most.

In addition, Miyasaka said many fire paramedics in his low-income, mostly Latine and Black service area write off patients’ complaints as overreacting and label them as “elevated hysteria.”

“[There was a time when we were called out to] a lady who’s been complaining about being sick for three days, and just feels weak. The patient wants to go to the hospital or get in our ambulance. When we started transport and wrote our own assessment, we found out she's actually having a stroke,” said Miyasaka.

System reset

EMTs are trained to deliver basic care, but they defer to the directions of fire department paramedics on a call, who have the highest medical authority on scene. A basic life support patient, or BLS, is transported by EMT., But a more severe acute life support patient, an ALS, must be transported by paramedics, whose job requires more training. When a patient arrives at the hospital, either EMTs or paramedics give a verbal report to hospital staff, while uploading the patient care report on an iPad to the hospital database.

Los Angeles County is the only system with these separated categories according to EMTs AfroLA interviewed. With a population of more than 9 million, there are more people here in need of medical care. Strikes for higher wages and staffing shortages result in more hospitals on diversion status and higher ambulance wait times. Other cities in California and across the country have more ways to manage and mitigate these problems.

How patients are classified by first responders is a critical factor in getting them the help they need quickly, said Chief Tucker. Miyasaka said fire paramedics sometimes pass off a patient whose condition is misclassified.. This causes issues when they get to the hospital because the wrong bed is assigned. He said he or his partner have made the correct assessment on the way to the hospital just in time to get the patient the correct care.

Miyasaka said having EMTs in charge of what happens to patients in both critical and noncritical conditions when they call 911 would be a more effective way to manage patient care.

“Triaging patients upstream of the ER” to determine if they need to be taken to the hospital, or whether the ER is even the best place for them, is the first step to getting back more resources and saving critical ER capacity, explained Dr. Clayton Kazan, incoming president of the California’s chapter of the National Association of EMS Physicians (Cal-NAEMSP), in an email to AfroLA.

“Some fire departments have had success triaging patients in dispatch, with the help of specially trained nurses, before sending EMS resources,” explained Kazan. Dispatching alternative response units such as community paramedics, response units staffed with a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, or mental health units are other strategies that could be implemented. “And, when patients’ needs can’t be met in the field, transporting them to alternate destinations like psychiatric urgent care centers and sobering centers can save desperately needed ER capacity.” Diverting people who don’t need a hospital in the first place, who have less severe injuries or conditions, could also ease the strain on an overwhelmed system. “We need to improve access to urgent care centers and awareness of their capabilities,” he said. Many people aren’t aware they can use an urgent care center, even with Medi-Cal.

For Miyasaka, solutions to address long wait times and biases in patient care involve a complete system overhaul. A better system to penalize hospitals with excessive offload wait times would help immensely, he said, but that’s not a silver bullet.

Slye told AfroLA that private ambulance companies like McCormick would rather pay fines than pay to staff more ambulances.

Miyasaka echoed Slye’s complaints, and said the company should also be more focused on the well-being of employees and patients than the bottomline. At McCormick, Miyasaka said the pay and hours are dismal. Additionally, EMTs are not always treated kindly and don’t always have their concerns taken seriously by their supervisors, resulting in suspensions.

On a cold night, a supervisor once wrote up Galvan for having a warmer jacket on top of his uniform while holding the wall with a patient. Galvan said two or three times with that kind of write up will get you suspended, which signals to him that management cares more about micromanaging uniforms than the physical wellbeing of their workers.

Even with EMT shortages, Galvan says that since January, he’s seen more suspensions than in all of 2023. Similarly, said Miyasaka, “I don't know [any] person at my company that hasn't gotten a write-up or suspension. Work turnover rates are insane.”

“We all get into being an EMT because we want to be out there helping other people with their emergencies. For some of these patients…who are repeat callers being taken to the hospital again and again, [they are] taking up space for others,” Miyasaka explained. But, sometimes he said he feels EMTs are a “glorified taxi service.”

Riverside Community Hospital piloted an ER Wait Time text service, which allows patients to see wait times in real time and plan their care visit around that information. In Glendale, 911 dispatchers allocate some emergency calls to police or to mental health services. Triaging patients in this way cuts down on hospital wait times because ambulances are freed up to deal with emergencies instead of calls that aren’t strictly life or death.

There are also mobile EMS units, staffed by trained paramedics, that transport elderly patients and others who need to go to the hospital more often, leaving ambulances to address emergencies. Street medicine services, such as clinics led by USC’s medical school and nonprofits like the Sidewalk Project, bring services straight to people experiencing homelessness, who are more likely to visit the ER for treatment more in line with a primary care provider, and help relieve the strain on an overburdened system.

“The current situation is so bad that ambulances are held at the hospitals, sometimes for hours, waiting to offload their patients, and the result can be prolonged response times for EMS patients with critical needs,” said Kazan. “Emergency rooms are drowning under the burden of filling in all of the gaps in the healthcare system, in addition to caring for the critically ill patients that they were intended for.”

Whether it’s specialty mobile units, analyzing EMS data to find ways to improve systems or triaging patients before reaching the ER, change is desperately needed.

Tan, who said hospital inpatient overcrowding is the underlying cause of ER overcrowding, describes an imminent breaking point in the system. “We cannot continue to cram patients unnecessarily through this terrible bottleneck of the ER that comes at extreme costs and impacts the ER's ability to handle the high acuity patients that they were designed to handle.”