I spent months talking with people whose loved ones have serious mental illness. Here’s my family’s story.

This story was originally published in inewsource with support from the 2022 California Fellowship

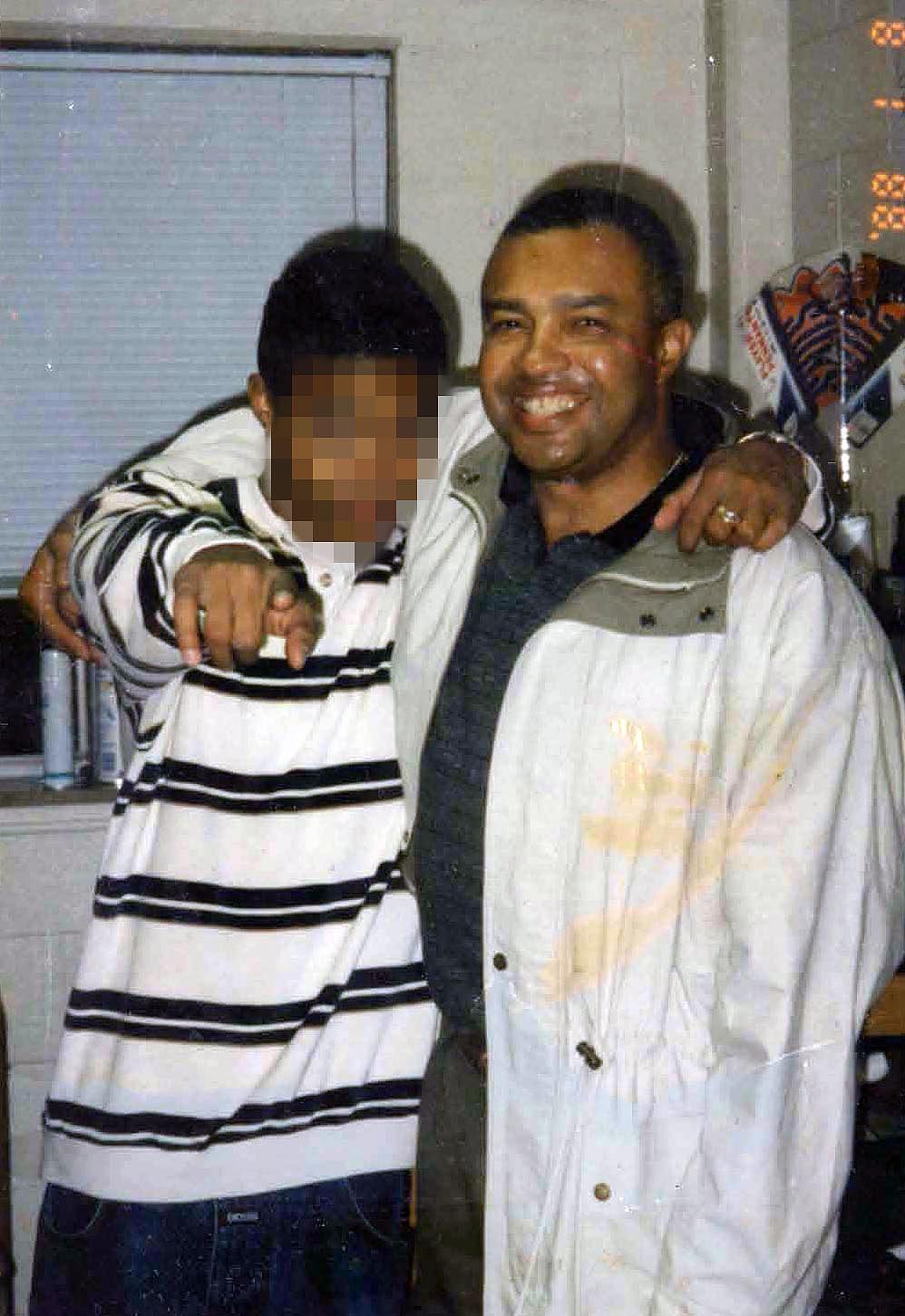

inewsource investigative reporter Jennifer Bowman's stepfather, Harvey "Mac" McDonald, right, stands next to his son in this undated photo. inewsource obscured McDonald’s son’s face to avoid identifying him.

(Courtesy of Harvey McDonald)

I wish this was a chance to tell you about my stepbrother in his own words: How he has this amazing ability to remember little details about people from years ago and a talent for fitting in wherever he goes.

I wish I could show his photos, so you could see why many of my friends had childhood crushes on him. I wish I could point out all the ways his personality comes from his father, my stepdad, who passed along to his only son the knack of making a stranger feel like a lifelong friend.

But instead, this is the story of how my brother hasn’t gotten the help he deserves — and what it’s meant for our 75-year-old dad, Harvey “Mac” McDonald, who has shouldered the emotional toll of trying to convince him he needs help.

“Let him go out and have a life where he can work a job and just live,” Mac told me earlier this month. “He doesn’t have to come back to me. Just go live. That’s all.”

Last week, inewsource unveiled a reporting project investigating when involuntary mental health treatment fails to serve some of the most severely ill Californians. My series doesn’t paint a rosy picture: After conversations with nearly 40 people and months of reporting, I centered our stories on families left hanging in the balance as they try to get their loved ones into treatment.

There was Anita Fisher, whose son had yet again stopped taking his medication; Mimi Murray, who feared her son’s struggles would persist into her 80s; and Anastasia, who held back tears as she told me about her unsuccessful push to get her son on a conservatorship.

Their pain was gut-wrenching — and familiar.

I haven’t seen or spoken with my brother since 2019. Last our family knew, he does not accept his schizophrenia diagnosis and hasn’t received consistent treatment. He’s been homeless, gone missing and has spent at least a few days in jail.

It’s been hell. Because of his mental illness, my brother is convinced that members of our family are brain-hacking him. (We are not.) He’s contacted some of our employers, attempted to secure restraining orders and threatened violence against my parents. He showed up once to their house, but they weren’t home.

Admittedly, I’ve felt all kinds of ways. I’ve been angry, even a little scared — and then I’ve felt guilty for being angry and scared. I’ve wondered whether I’m making the right decision by staying away for my own peace of mind, or if I could do more.

inewsource investigative reporter Jennifer Bowman, right, as a child sits next to her stepbrother for dinner at their family’s Chula Vista home in this undated photo. inewsource obscured his face to avoid identifying him. (Courtesy of Harvey McDonald)

But mostly, I think about how my brother is living a false reality in which he thinks we’re actively trying to hurt him. That we are doing and saying awful, horrible things. He’s lost trust in the people who he thought loved him. What a scary, traumatic place that must be.

Added to the heartbreak is what it’s done to my stepdad.

To know Mac is to love him: He’s the life of the party with dance moves that put youngsters to shame, and his booming voice is a mainstay at our family get-togethers. I grew up hearing that booming voice proudly boast about his son, too.

But there’s an emptiness to all of this, and I’ve seen my stepdad carrying on in the absence of hope these past couple years. He wants my brother to get better, but he doesn’t have much faith.

He also regrets the time missed with his kids during his more than 30-year career in the Navy, and wonders if he missed the onset of my brother’s illness.

“Maybe I just didn’t see it,” my stepdad said. “And I blame myself that I didn’t see it.”

inewsource investigative reporter Jennifer Bowman, left, dances with her stepfather Harvey “Mac” McDonald at her 2019 wedding in North Carolina. (Courtesy of Stephanie Parshall Photography)

My stepdad sent money to my brother when he could. He made phone calls in San Diego and beyond trying to get him housing. He encouraged him again and again to seek treatment. None of it worked.

Earlier this year, police got involved. Both my stepdad and mother endured months of threatening phone calls day and night from my brother. He had threatened to hurt them — and himself — before. But this time, he repeated those threats while seeking help at a local hospital.

Officers arrested my brother in January. There is now a criminal protective order that prohibits him from contacting my parents.

Court records show my brother has agreed to mental health treatment. Lawyers involved in the case told my stepdad that my brother isn’t interested in speaking with him.

Is my brother a good fit for a mental health conservatorship? I don’t know. Even after months of reporting on the topic, done with the help of a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism fellowship, I have no firm answer on whether it would help in our family’s case.

But I do know this: My brother was in medical school just five years ago. And during one of the last times I saw him, he held my daughter and talked about wanting kids of his own one day. Now, he’s living a nightmare in which he believes his family is hurting him — including his father, who in fact loves him very much and also is hurting.

My stepdad has heard all the advice, and he has little patience for it. He’s been told he should have involved the police much earlier, that he should use tough love. Or, on the contrary, that he shouldn’t be so heartless about his son. Some relatives have encouraged him to pray on it — to which he scoffs and says, “I’ve seen what God can do and what God cannot do.”

It’s been difficult for him to maintain relationships with family as they, too, have been impacted by my brother’s mental illness. He told me he’s asked other relatives to notify him when my brother has contacted them, but to say nothing more.

“Don’t tell me about praying, don’t give me any pragmatic shit,” he said. “I’ve been through all of it more times than any of you guys. I know you guys are hurting. I know you’re suffering.

“But you haven’t suffered the way we are.”