Imperial County has one maternity ward left. These women are bearing the risks

The story was originally published in inewsource with support from our 2024 California Health Equity Fellowship.

Andreanallely Barajas, 4 months pregnant, sits in her family home in Holtville, Calif. days after returning from the hospital in San Diego on Aug. 22, 2024.

(Philip Salata/inewsource)

Why this matters

When El Centro Regional Medical Center shuttered its maternity ward in 2023, hundreds of patients were funneled to the last facility in the county at Pioneers Memorial Hospital. Others have been seeking services beyond the county.

Vanessa Mendoza wouldn’t risk giving birth in Imperial County hospitals – but when her time came, not all went as planned.

The first time she gave birth, she lived in San Diego and delivered at a hospital near her home. This time, despite now living in Imperial County, she would pack up and head back to San Diego, over a hundred miles and almost two hours west.

“Mamas talk,” she said. Many raised concerns that Imperial’s hospitals are too isolated and lack trauma care – if something went wrong her options were limited, she said. She didn’t want to risk her or the baby having to be flown out to another hospital.

Then, days before she was due, her water broke and she was still in the valley – so she made a wager. It was winter, it was hailing and foggy, it was 1 a.m., and the trip meant a 4,000 foot elevation gain through the mountains.

She just needed time to get to San Diego – her first birth took 20 hours, and she wasn’t in any pain or feeling contractions yet.

“I think we’ll be fine. Let’s go,” Mendoza told her husband.

When they reached the Golden Acorn Casino off Interstate 8 in the Campo Indian Reservation, a landmark that to locals means having arrived at the height of the pass, she felt an immense pressure and pain.

Twenty minutes later, she gave birth to her son in the passenger seat of the car while her husband sped through rain down the highway to Grossmont Hospital in La Mesa.

“I wasn’t really fully understanding what was happening until it happened,” Mendoza said. “This isn’t a movie, this is real life.”

A view from Interstate 8 near the Golden Acorn Casino on the Campo Indian Reservation on Aug. 30, 2024.

(Philip Salata/inewsource)

At the time, soon-to-be parents living in Imperial County had more options for giving birth. Two local hospitals had maternity wards: El Centro Regional Medical Center and Pioneers Memorial Hospital in Brawley. Together, they had just over three dozen beds for birthing parents, according to a physician who delivers babies in the county.

Then in January of last year, El Centro Regional closed maternity ward, citing financial trouble. The closure, which administrators announced just two weeks before it took place, funneled hundreds more birthing mothers to the hospital in the northern end of the county, and left many others to look beyond the county for services.

What played out was part of a national trend. Since 2011, a quarter of rural hospitals in the U.S. have ceased to provide obstetrics services, leaving more than half of rural hospitals in the country without a maternity ward. In California, almost 60% of rural hospitals lack one, pushing patients to seek care elsewhere in a geographically expansive state where average driving times to the nearest hospital with maternity services already near an hour.

Many Imperial County residents already face about the same driving time to get to Pioneers, depending on where they live – and that’s if beds are available. Those traveling beyond the county for care – more than 13,000 patients in 2022 alone – could face trips of around two hours, and that’s without extreme weather events and possible road closures causing delays.

Doctors in Imperial County are sounding alarms. Losing El Centro’s maternity ward has put pressure on already limited resources, they say. inewsource spoke with several doctors in the valley who said that more doctors, specialized nurses and expanded facilities are needed, quickly.

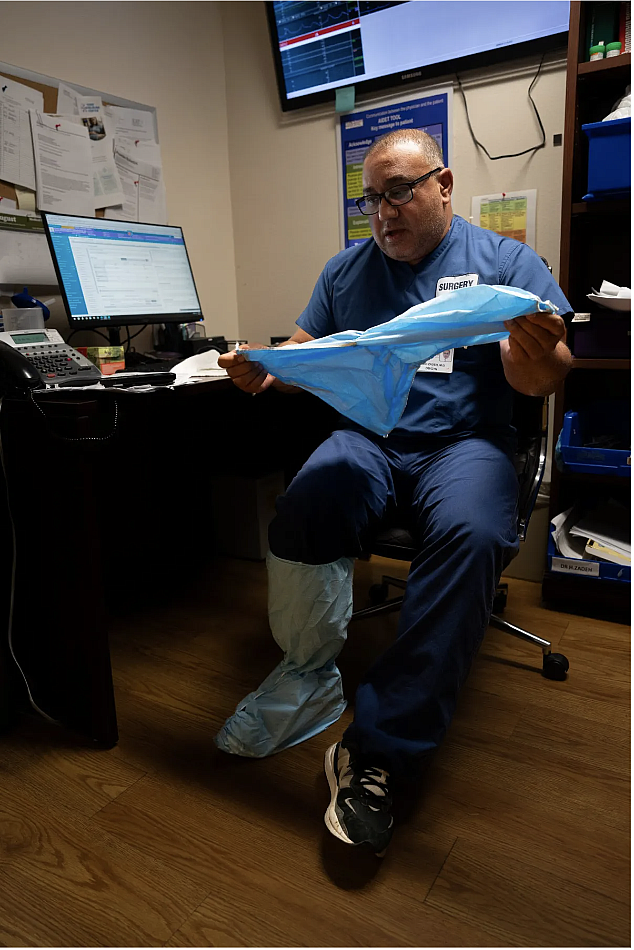

“We’re working at 110% of our capacity,” said Dr. Hamid Zadeh, an OBGYN doctor at Pioneers Memorial. “We just don’t have the resources.”

“They’re trying their best, but it’s not enough,” said Dr. Elias Moukarzel, a gynecologist at El Centro Regional, referencing Pioneers, which took on more patients after El Centro discontinued maternity services. “They were not ready. It was just thrown on them.”

Soon-to-be parents also said they could tell hospitals were struggling to keep up with the demand.

“They have a lot of work and they’re understaffed,” said Itzel Torres, another Imperial County resident who decided to give birth in San Diego.

“They discharged me. They said everything looked okay, but at the end of the day, it wasn’t,” said Andreanallely Barajas. It was her first pregnancy, and she had been vomiting for days. She was worried about her baby, so she decided to go to the emergency room at Pioneers Memorial. After being sent home, her mother drove her west where the doctors had a different perspective on her condition.

“I had to go to San Diego to be admitted for four days, and then I went again for three days.”

Sun sets over Pioneers Memorial Hospital in Brawley, Calif. on Aug. 8, 2024.

(Philip Salata/inewsource)

Helicopter ambulance nurses cross tarmac toward the helicopter for a 911 call on July 10, 2024.

(Philip Salata/inewsource)

Meanwhile, few solutions appear to be materializing anytime soon.

Local leaders say vast stores of lithium, a metal critical to the production of electric car batteries, under the Salton Sea could fuel the green economy and bring more business and people to the region – growth that could sustain more robust medical services.

But attracting that economic investment requires some commitment to improving basic services in the county, such as health care.

Some, including El Centro Regional’s CEO, Pablo Velez, are hopeful a recently passed state law that aims to consolidate Imperial County hospitals under a single management district would reduce costs, improve access to resources for providers and patients and help increase how much insurers reimburse for services.

But that plan has faced pushback from the Pioneers Memorial Health District which filed a lawsuit against the state, saying that it did not give voters a chance to weigh in.

Pioneers CEO Christopher Bjornberg did not respond to inewsource’s attempts to ask why PHCD opposes the new law or to discuss other concerns raised by patients and doctors about the quality of services at Pioneers.

Many doctors, including Zadeh and Moukarzel support the redistricting and say that there is no time to lose.

“The way that this is going, it’s going to collapse,” Zadeh said. “So this whole unification of the districts is a great idea and we need everybody’s backup on it.”

Meanwhile, an already difficult situation has gotten harder.

“Taking care of pregnant women used to be a lot of joy,” Zadeh said. “But right now, with the amount of stress that we are enduring, it doesn’t have the same satisfaction.”

Dr. Hamid Zadeh, OBGYN, sits in his home in El Centro while juggling calls from the maternity ward at Pioneers Memorial Hospital on Aug. 23, 2024.

(Philip Salata/inewsource)

Costs of doing health care business

El Centro closing its maternity ward is one consequence of the financial challenges facing rural hospitals across the United States. For many rural hospitals, the math doesn’t add up for sustainability. Doctors say that needs to change.

Hospitals need to make money to grow and sustain essential medical services. But the more profitable services often are highly specialized ones, which also happen to be more expensive to maintain. Meanwhile, many rural hospitals serve communities that are more economically challenged, which means more patients on public insurance plans, which tend to reimburse at lower rates than private plans.

More than half of Imperial County’s population relies on public health insurance.

Velez, the El Centro Regional CEO, says the low reimbursements and high costs led to the dissolving of its maternity ward.

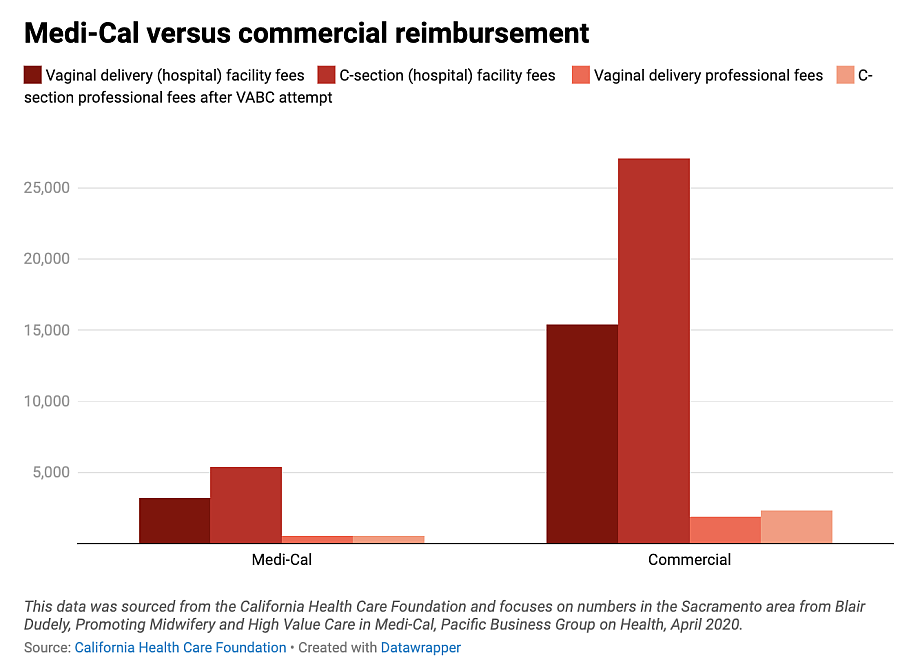

Often the cost is higher than the reimbursement. The average cost for a cesarean section in California under Medi-Cal is $7,500, including facility costs and professional fees. For Medi-Cal plans, reimbursement rates are often five times less than private plans. The reimbursement for a C-section from Medi-Cal can be around $6,000, while private insurers may payout $32,000.

“The hospitals have been losing money, especially on deliveries,” said Zadeh, the Pioneers Memorial OBGYN.

Obstetrics units need highly trained staff on a 24-hour basis, specialized equipment and space dedicated to labor, delivery and recovery.

That reality poses a challenge for rural hospitals: How do they sustain specialized staff in a region that sees a lot of turnover and provide quality services despite the lack of resources?

Dr. Hamid Zadeh puts on his PPE on his way to perform a caesarian section at Pioneers Memorial Hospital on Aug. 8, 2024.

(Philip Salata/inewsource)

Since the closing of El Centro Regional’s maternity ward, Zadeh, one of the primary obstetricians at Pioneers Memorial, says the hospital has seen an uptick of almost a thousand more births that year. Zadeh says he has been working 80-100 hour weeks and sometimes giving half his salary away to a midwife he hires on his own dime.

“When people talk about the weekend, I don’t have an understanding of what that means.”

He says hospital leaders are aware of the situation but stay mute on the topic. Meanwhile, he and other providers must continue to care for patients: “When an emergency happens, and the doctor or the provider is at that emergency, the deliveries are not stopping, so somebody still needs to provide care for those patients that keep coming through the door,” he said.

He says more nurses and providers are urgently needed, and the state increasing reimbursements would help.

When complications arise

This summer, Barajas was among the patients who came to Pioneers Memorial seeking emergency help.

Fourteen weeks into her first pregnancy and vomiting up all the food and water she took in, she was worried and had no idea how what she was experiencing could affect her child.

Barajas waited for seven hours in the Pioneers Memorial emergency room bending in pain, and after finally being seen she was told she should go home.

“I wasn’t able to eat for at least two weeks, and they did not pay attention to that,” Barajas said.

So her mother drove her to a hospital in San Diego, where her boyfriend later joined to stay with her.

It turned out Barajas had a stomach flu and severe dehydration. It took doctors four days to bring her back to her feet.

Barajas and her boyfriend Nicanor Verdugo sit on the living room couch in their family house in Holtville, Calif. on Aug. 22, 2024.

(Philip Salata/inewsource)

The experience shook Barajas, enough so that she started planning on having her child outside the county. She and her boyfriend pulled together funds to buy a used car, some of which came from his job mowing lawns in their town of Holtville, a job he speaks about with tenderness and pride.

inewsource recently held listening sessions with Imperial County residents to hear about their experiences and challenges seeking health care. In the sessions, several people shared stories similar to Barajas’: They complained of not being taken seriously in the local health care system only to leave the county for care and find out their concerns were real and necessitated critical intervention.

Community members also said health care workers in the valley face challenging work environments, including being overworked.

Zadeh confirmed the observation. He added that in San Diego doctors have a wide array of specialized colleagues within reach to help in emergencies. In the valley doctors “don’t have that luxury,” Zadeh said. “We have been trained to be on our own and to do the best we can.”

Barajas and her boyfriend Nicanor Verdugo speak together in their family kitchen recalling buying their new car on Aug. 22, 2024.

(Philip Salata/inewsource)

In emergencies, every minute counts. Studies show that the longer the distance pregnant people must travel, the higher risks for complications or adverse outcomes such as blood clots, uterus rupture, hemorrhaging, bleeding, severe dehydration or other conditions needing intensive care.

Yet hospitals in Imperial County only have Level 4 trauma centers – the second lowest level, focused mostly on stabilizing and preparing trauma patients for transfer to other hospitals.

Pioneers’ neonatal intensive care unit also provides the second-lowest level of services, which means infants born prematurely and in need of intensive care must be transferred to an out of county hospital. Zadeh says Pioneers can’t care for any infants delivered before 35 weeks. Other patients often requiring transfers include those with high risk pregnancies, such as having to do a vaginal delivery after having a c-section, and those needing specialized surgeons who aren’t on staff, Zadeh said, adding that patients with preterm labor and any complications to the fetus usually lead to a trip out of the county.

Being in an isolated desert valley surrounded by mountains makes transfers more challenging.

An ambulance ride could take hours, a helicopter evacuation could take from thirty minutes to an hour, or longer if there are complications. Bad weather, such as black ice or fog, could make leaving Imperial County through the mountains more treacherous. A single mountain accident can cause significant delays.

And helicopters have restrictions on when they can fly. If it’s too hot the local helicopter ambulance cannot take off.

Barajas pets her dog in her dining room on Aug. 22, 2024.

(Philip Salata/inewsource)

Bringing it home

Mendoza, who gave birth in her car to a son who is now a thriving toddler, has since been brewing on what she can do to bring more resources to Imperial County for women in need of maternal health care. She said her doctor in San Diego inspired her.

She is a counselor at a school in Brawley, and has been considering ways to connect women with more information about prenatal care, and the risks women face being pregnant in the valley which is riddled with agricultural pollution and toxic dust from the Salton Sea.

A tractor cuts through the dust in a field near Brawley, Calif. on Aug. 6, 2024.

(Philip Salata/inewsource)

Moving back and forth between the valley and San Diego weighed on her. Images of polluted fields outside her window were reappearing in her dreams.

“Having to go back and forth with the change in the weather, the change in the altitude, even my allergies….it’s like you walk into a different world when you come back to the Imperial Valley.”