Imperial County sees chance to bring addiction treatment ‘into modern times’

Megan Burks is the Speak City Heights reporter for KPBS. Her work focuses on community health in the City Heights neighborhood of San Diego. This project was produced for the 2015 California Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of USC's Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

A tour of El Centro with Susan Ireland takes a quick 15 minutes. It covers less than 10 square miles and spans about four years of her life. But it feels like a lifetime.

To the right there used to be an abandoned house where she would get her heroin fix most days. A block down, there was once an apartment complex where she got high – or stripped copper pipes so she could get money to get high. See that stack of pallets next to the warehouse? She used to shoot up back there. Cross the highway and there's the apartment where Child Protective Services showed up to take her kids. That's the day she says she lost it.

"I overdosed on heroin and I was staying in a motel. The guy that worked at the motel found me, raped me and called the cops. I woke up in the hospital two weeks later, clean and sober and pregnant," Ireland said. "That's why I'm clean and sober today."

'Saddled with a one-trick pony'

The pregnancy and legal trouble pushed Ireland into a parenting class for women struggling with addiction. That introduced her to group therapy and put her in touch with a psychologist. Today, she has seven years of sobriety.

But many people with substance use disorders never end up in the mental health system. They end up in a prison Alcoholics Anonymous group, the court system orders them to a group home, or family members push them into detox.

Those rarely address the underlying medical conditions driving their behavior.

That's why doctors are hailing a change to Medicaid they say could take addiction treatment out of the hands of amateurs and use science to get people well.

In August, California became the first state to opt into a Medicaid pilot that will allow health providers more flexibility in billing for substance abuse treatment. It's expected to improve access to mental health care and residential treatment for individuals battling addiction at a time when the recovery field is slipping further from the medical community's grasp.

"We have kind of been saddled with a one-trick pony in treating substance abuse in this country for a long time," said Michael Horn. He heads Imperial County Behavioral Health Services, where Ireland found help.

Broken glass litters an empty lot in East El Centro on Aug. 27, 2015.

Horn was referring to group therapy. Most private residential treatment centers, support groups, faith-based programs, managed care organizations – even his department – rely on it.

"Modern substance abuse treatment started with AA programs. Everything was geared toward not drinking, and to give yourself over to a higher power, and they had a whole system of steps that you had to take," Horn said. "And that's been pretty much our system for many, many years."

And it's largely the only kind of addiction treatment for which Medicaid – or Medi-Cal here in California – will reimburse, Horn said.

Even that support has been scant. About five years ago, Imperial County ended most of its group sessions because the Medi-Cal reimbursement rate for the service was cut in half. It wasn't enough to cover overhead costs.

Similar cutbacks are happening nationwide.

From 2003 to 2013, the number of state and local facilities treating substance abuse dropped 25 percent, according to the federal government's Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Meanwhile the number of for-profit facilities, which tend to favor group sessions led by certified drug counselors instead of licensed therapists, grew 34 percent.

In Imperial County during that time, residential centers fed mainly by behavioral health referrals also shuttered. But in a county known for low incomes and high unemployment rates, it wasn't for-profit centers that stepped in. It was churches like Turning Point.

'God gets all the glory'

The small, squat compound of buildings off the highway in nearby Holtville is one of about seven sober-living homes in the area run by religious groups. It offers formal anger management classes, but house supervisor Luis Barajas said the focus is on faith.

A mural welcoming people to Turning Point Men's Home in Holtville, Calif., is pictured, Aug. 27, 2015.

Barajas said he was addicted to methamphetamine for 35 years before a court ordered him to Turning Point. Now he shares the scripture that helped him sober up.

"Focus on God and let him lead me through my life. Before it was the drugs leading me through everything," said Barajas, who was estranged from his wife and sons when he entered Turning Point. "God gets all the glory in this because he tells us in the Bible, 'I will give you everything that the locusts have eaten – have taken from you.' I'm proof that that happens because everything that I lost got restored back."

Barajas said about 1,000 men come through his doors each year – about half because of court orders. Barajas said he doesn't have data on how many of them stay clean but said there's no better way to help addicts.

Luis Barajas gives a tour of Turning Point Men's Home in Holtville, Calif., on Aug. 27, 2015.

"I had a psychiatrist tell me one year, 'How many years did you go to college to learn how to do this?' And I told him 'I've never been to college.' And I asked him, 'How many years have you been and addict?' He says, 'I've never been,'" Barajas recounted. "So how do you know how that addict's feeling? How can you tell what that addict's going through? I know what he's going through because I've been down that same road he has."

Julie Myers, a San Diego-based psychologist specializing in addiction treatment, doesn't dispute the value of religion and community in getting clean.

"But the truth is that there really is no data out there that says AA works or that there's any particular model of self-help that works," Myers said. "The data does show that something like a third of the people do have a spontaneous remission of their addiction, and as people age they reach this maximum of using and then they go down."

"But where it's particularly important for expansion, is the underlying mental health conditions," Myers said.

In 2013, 45 percent of individuals who reported being in treatment also reported a having a mental disorder, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

SAMHSA data also shows private, for-profit recovery centers were about 20 percent less likely than county- and city-run facilities to screen for mental illness.

Imperial County's Michael Horn said he sees the new Medicaid program as not just a way to bring these individuals more options in the short term, but to discover new ways to help them in the long term. He pointed out that under the current model of treatment, reliable research to further addiction medicine is hard to come by.

"The problem with it is the fact that it's anonymous, right? So millions and millions and millions of people have entered into various programs that use the 12-step model but we don't know who didn't benefit from it, who didn't succeed," Horn said. "The goal is to finally get into modern times in the treatment of substance abuse."

'It was the combination of everything'

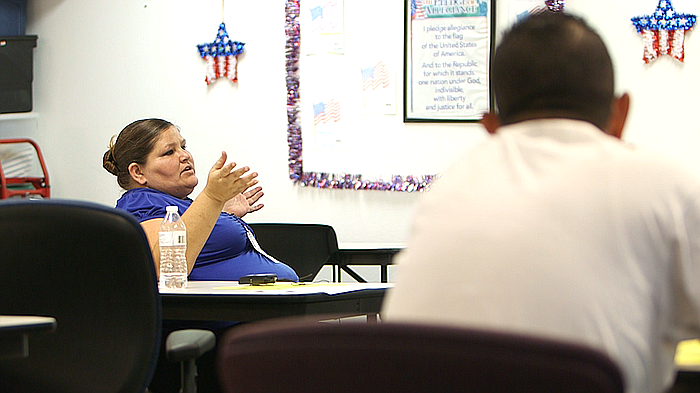

Susan Ireland facilitates a SMART Recovery group in El Centro, July 6, 2015.

So what would modern substance abuse treatment look like? Horn likes to direct patients to a program called SMART Recovery (SMART stands for Self Management And Recovery Training). It's the closest thing he sees to modern treatment in lieu of one-on-one therapy. It blends the group model with coping tools culled from cognitive behavioral therapy. Myers helped develop curriculum for the program.

Susan Ireland, whose 10 years of heroin, methamphetamine and alcohol addiction came to a head when she moved to Imperial County, is now facilitating SMART Recovery sessions throughout El Centro and neighboring Brawley.

Ireland went through the program herself and said she uses it on a daily basis – like when her son recently wanted to leave home because she challenged his drug use. She said she used something called an ABC analysis, which involves exploring your beliefs about the situation and their consequences.

"The belief was he's just going to go nowhere in his life and become the person that I used to be. And the consequence that would have come out of it was he would be leaving," Ireland said. "So I changed that belief around. Maybe this would be the best thing for him if he was to leave the situation, but not go to his friends and go to a recovery program or group. And what would be the consequence? I can actually help support him and we can learn to work together as a family, as a little unit."

Now her son is sober and a family therapist is coming to their home on a regular basis.

Ireland said what SMART Recovery and a therapist taught her about managing anger and anxiety, and understanding where they come from, has been instrumental in her recovery.

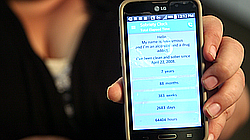

Susan Ireland displays a sobriety clock on her smart phone on Aug. 27, 2015.

But Ireland said it was the combination of everything – the professional treatment, SMART Recovery groups, AA and Narcotics Anonymous – that got her clean and keep her clean today. She's working through the 12-steps program a second time. This interview was step five.

"I want to show you something," Ireland said, opening a sobriety clock application on her smart phone. "I have 7 years, 88 months, 383 weeks, 2,683 days, 64,404 hours clean and sober."

Knowing those kinds of success stories, Horn said he doesn't want to block the paths to recovery laid by religious groups and former users in Imperial County. He just hopes the new funding will open a few more.

California counties must apply to participate in the Medicaid pilot program for substance abuse treatment. Both Imperial and San Diego counties plan to participate.

[This story was originally broadcasted by KPBS. Photos by Nicholas McVicker.]