In Indianapolis, a baby dies every 3 1/2 days

This series was produced as a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism's National Fellowship.

Other stories in the series include:

Nurse-Family Partnership nurse Amber Burleson shows D'Ondra Gomes, holding her 6-month-old son, Kai'Dian, what to do if her baby starts to choke. Gomes lives in Indianapolis.

INDIANAPOLIS — "How would you tell if he was truly choking," nurse Amber Burelson asked D'Ondra Gomes, who was holding her 6-month-old son, Kai'Dian, while sitting on her couch last fall.

"Gagging? Color in his face?" Gomes said.

"If he's making noise or if he's coughing, he's still breathing," Burleson said.

The nurse demonstrated CPR on a plastic baby doll. After she was finished, Kai'Dian grabbed the doll and started playing with it.

Gomes picked him up. "He keeps me on my toes. He keeps everybody on their toes," she said. "I didn't expect to be a mom at 21, but it's all worth it. For him."

Burleson works for Nurse-Family Partnership, which sends nurses into the homes of first-time, low-income moms, from early in their pregnancies until their babies turn 2.

She was visiting Gomes' home on the northeast side of Indianapolis, where Gomes lives with her son, parents and brothers. They reside in the ZIP code that, from 2010 to 2014, had the most infant deaths of any in the state. A baby dies almost every month in the 46226. Indiana has the eighth-highest infant mortality rate in the nation.

Gomes has two of the top three risk factors for losing a baby in Indiana, according to a 2014 state report. She is on Medicaid and gave birth between the ages of 15 and 20. However, she went to at least 10 prenatal visits.

She also has help, from social service agencies like Nurse-Family Partnership, and, perhaps more important, her family.

"I have a lot of clients with zero support," said Burleson, the nurse. "A lot of people don't have the support system she has. A lot of people don't have the love she has."

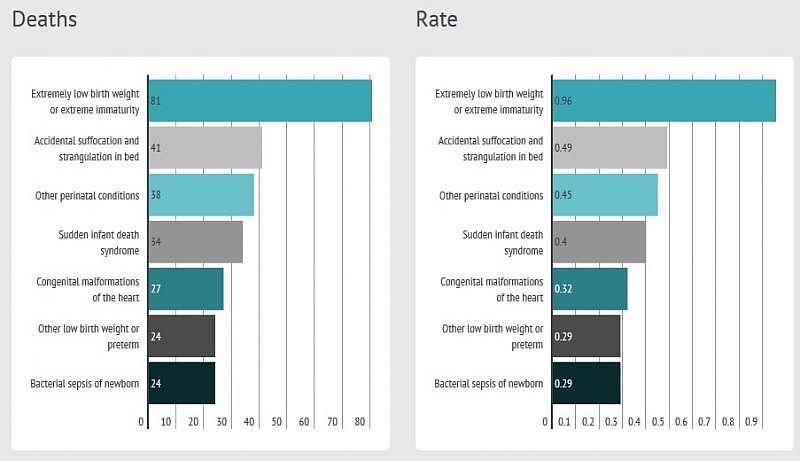

In Indianapolis, the state's capital and largest city, the risk factors for infant deaths are similar to big cities across the nation: poverty, lack of nutritious food and health care, racial segregation, high rates of teen pregnancy. So are the causes: premature birth, low birth weight, suffocation during sleep.

In the past 30 years, Indianapolis' infant mortality rate has decreased from 14.2 per 1,000 live births, to just more than nine per 1,000 live births today. In the past five years, the rate has dropped 10 percent.

Even so, a baby dies in this city of 850,000 every 3 1/2 days.

A legacy of facing infant mortality

In 1987, Indianapolis had the highest black infant mortality rate in the United States. Local health officials formed a coalition, the Indianapolis Campaign for Healthy Babies. They opened new health centers, expanded existing clinics and enhanced services for pregnant women and infants.

Porsche Bancroft, of Indianapolis, left, gets some assistance from BABE (Beds and Britches Etc.) store manager Debbie Busbin.

In 1995, the Marion County Health Department started the first Beds and Britches Etc. store in Indianapolis. As part of that program, women earn coupons by going to prenatal visits, Women Infants and Children appointments and pregnancy education. They can use the coupons to buy baby supplies from cribs to clothes.

On a fall day at a BABE store in south Indianapolis, Porsche Bancroft stopped to get supplies using coupons she earned from attending breastfeeding courses. She has three kids — ages 6, 4 and 1. She fed the first two formula and is breastfeeding the youngest, thanks to what she learned at the classes. "It's the healthy choice," said Bancroft, 22, a parking attendant.

Research shows that breastfeeding lowers infant mortality because it prevents and reduces the severity of infections, improves respiratory function and causes babies to be more easily aroused from sleep.

"I always do extra classes for coupons," Bancroft said. "It helps me get stuff for my kids. Say you're out of money one week, like today, payday's not till Wednesday. I got two packs of diapers."

Healthy Start has long history in Indy

An Indianapolis chapter of Healthy Start was founded in 1997. The federal program works to get women health care early in their pregnancies.

Victoria Ballard, community engagement coordinator for Indianapolis Healthy Start, said her client base includes moms who have high rates of depression, lack access to nutritious food and don't have cars. It takes 3.5 hours, round-trip, to get to the nearest hospital by bus.

Healthy Start focuses its efforts on the 10 Indianapolis ZIP codes with the highest infant mortality rates, located in the north-central part of the city. Ballard said poverty runs deep in some of these areas.

"You can't fathom a family who doesn't have a bed to sleep in," she said.

"You leave here, you go home and climb in your bed, and you literally have moms who don't have a place to sleep. They're literally on the floor in some areas."

Healthy Start helps fill in those gaps, providing portable cribs, transportation and education.

Myleea Davis stopped by the Healthy Start one day last fall to join a program to help her kick her cigarette habit. Smoking during pregnancy can cause low birth weights and harm a baby's lungs, heart and sleep arousal, potentially leading to sudden infant death syndrome. Baby & Me Tobacco Free provides free diapers to pregnant women who stop smoking.

"Can you imagine how much I'll save on Pampers and cigarettes?" Davis said, as her 1-year-old daughter, Diyah, chewed on a pencil and ate a sucker at the same time. Davis was due to give birth in four months, and also has a 6- and 4-year-old at home.

"You get pregnant and say, 'I'm going to quit smoking.' Next thing you know you're six months pregnant and you're still smoking," she said. "With all these children, I didn't want to be a smoker, anymore. I gave cigarettes 20 years of my life. I don't want to give them any more."

Healthy Start has also gotten Davis into stress management classes and treatment for high blood pressure and gestational diabetes.

City still has work to do

A mid-2000s study by the Marion County Fetal Infant Mortality Review project found that about 43 percent of the infant deaths in Indianapolis were preventable. Reducing the state's infant mortality rate by this percentage would put it just above California to have the lowest rate in the nation. Indiana currently ranks 43rd.

"We know we can prevent some infant deaths. We can't prevent them all," said Dr. Haywood Brown, an OB-GYN professor at Duke University Medical Center and chief elevator for Indianapolis Healthy Start. "We won't get to an infant mortality rate of zero."

But there are ways to reduce risk.

For instance, Brown said, women of childbearing age should take 400 micrograms of folic acid a day and control their diabetes, hypertension and weight. Also, women who have had previous preterm births are supposed to take progesterone to prevent another, yet only about half do.

He noted that the racial disparity in infant deaths in Marion County is as low as it's ever been, thanks to an improvement in the black rate. But he points out that many of the causes and risk factors for infant death are beyond the scope of the medical community.

"We're beginning to learn more about social-environmental interactions," he said.

"The impact of those things on African-Americans may be different because the stressors they live under. People are worrying about child care, worrying about transportation, worrying about worrying. Stressors can incite the uterus to empty early."

The parts of Indianapolis with the highest infant death rates are also the highest crime areas with the most police patrols, according to the Indianapolis Police Department.

"Living in violent neighborhoods is another stressor associated with bad birth outcomes," said Dr. James Collins, a professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University.

Black rate stands out

In Indiana as a whole, the death rate for African-American babies is nearly 2.5 times that of white infants, on par with the national disparity. The state has the second-highest black infant mortality rate in the country, behind only Alabama. The Indiana cities with some of the highest rates — Indianapolis, Fort Wayne, Gary, Evansville, East Chicago — are largely segregated by race, according to a racial distribution map created by the Demographics Research Group at the University of Virginia.

Dr. Virginia Caine, director of the Marion County Public Health Department, noted that black women are less likely to attend a prenatal visit in their first trimester, and more likely to have nutrient deficiencies that could be addressed at those doctor's appointments.

"Women need prenatal visits for a healthy pregnancy," she said. "The earlier they come during their pregnancy, the more the baby will benefit."

Certain infections also are higher among African-American women, she said, while their breastfeeding rates are lower, an activity that research has shown to prevent infection.

The top two causes of death for African-Americans, whites and Hispanics in Marion County are short gestation/low birth weight and congenital malformations, Caine said. For African-Americans and whites, the third leading cause is accidents, while for Hispanics it is maternal complications, namely gestational diabetes.

"I think we're very fortunate in Marion County," Caine said. "In the '80s, when they had the campaign for healthy babies and maternal and child health, they came together and have kept that bond of working together in our community. We're just very collaborative in our approach."

Nurses partner with families

On the fall day at the Gomes residence in central Indianapolis, nurse Amber Burleson went over holiday and seasonal safety with D'Ondra Gomes and her 6-month-old son, Kai'Dian. Burleson made sure the baby had a winter coat and the house had adequate heat.

Nurse-Family Partnership nurse Amber Burleson plays with 6-month-old Kai'Dian Gomes.

"Is he going to dress up for Halloween?" Burleson asked. "Just don't get him a mask that covers his mouth and nose and he can't breathe."

"I might dress him up as a Minion because he loves 'Despicable Me,'" Gomes said.

Burleson typed on her laptop while the baby tried to stand, wobbling like an intoxicated adult.

"With all he's doing, I wouldn't be surprised if by Christmastime he's trying to walk," Burleson said, adding: "As much as you can, avoid having breakable Christmas ornaments that he can grab. Same thing with candles."

"Ayy, yay," Kai'Dian said in baby talk. "Heh, heh, heeyyyy."

State officials see Nurse-Family Partnership as a promising solution for infant mortality. Gov. Eric Holcomb included $5 million in his proposed budget to expand the program in Indiana.

Almost 90 percent of mothers in the program initiate breastfeeding, compared to the statewide rate of three-fourths, while 60 percent quit smoking and the rest at least reduced their cigarette intake, said Lisa Craine, senior director for Nurse-Family Partnership in Indiana. A 2014 analysis found that for every 1,000 moms the program visited in Indiana, 3.4 infant deaths and 62 preterm births could be prevented.

The program has served 1,709 women since coming to Marion County in 2011.

'It takes a village'

D'Ondra Gomes has a part-time job at a local grocery store. Her parents help watch her son when she works and are there when she needs an emotional break. His father, who lives a 10-minute drive away, has him once or twice a week as well.

During the recent home visit, Gomes' dad, Lawrence Sr., a steelworker out on medical leave, sat at the kitchen table, wearing a white tank-top undershirt. The 49-year-old, who has "God" tattooed next to his right eye, said the family is lucky in another sense: Their street is maybe the quietest in the neighborhood.

"South of here is a lot of drugs, alcohol, teenage folks who think they're grown and do what they want to do," he said. "They have sex with this guy and that guy. But a lot of these kids are scared to tell their parents they're pregnant."

"My daughter took me out to lunch," he said. "Immediately I knew. 'Just don't tell me you're pregnant.' I needed a shot of tequila to make it go down easier."

The family doesn't believe in abortion, he said, so they committed to raising the child — together.

"It takes a village — and we got one," he said, admiring his 6-month-old grandson. "That's my right-hand man. I can't wait till he rides a motorcycle."

[This story was originally published by The Times Of Northwest Indiana.]

[Photo credit John J. Watkins/The Times.]