Irradiated, Cheated and Now Infected: America’s Marshall Islanders Confront a Covid-19 Disaster

This story was reported by Dan Diamond with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2020 National Fellowship and the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

How 100,000 Marshall Islanders Got Their Health Care Back

‘A shining moment’: Congress agrees to restore Medicaid for Pacific Islanders

Maitha Jolet photographed October 5, 2019 in Dubuque, Iowa, a member of a Marshallese community that relocated to the United States after their islands became contaminated by nuclear fallout from U.S. military testing in the 1940s and 1950s.

M. Scott Mahaskey / POLITICO

DUBUQUE, Iowa—The Covid-19 pandemic had already sickened their friends when it came for Nathan Nathan's wife, too.

It was April 20, Nathan recalls, and his 53-year-old wife, Neibwen Naisher—who was always smiling, he says, who was never sick or complained—was gasping for air in their home in this small Midwestern city.

"She couldn't catch her breath," Nathan tells me through an interpreter. "I told her to go to the emergency room, to get checked out."

It was the last time they spoke. A whirlwind followed. A nine-day hospital stay. A funeral in May.

And later, nearly $120,000 in medical bills for his dead wife's care—including a new $14,135 bill that Nathan received this month and couldn't possibly hope to pay. He was laid off this spring as a laundry worker by the same hotel where his wife worked as a housekeeper. Neither had health benefits.

In many ways, it's the same catastrophe that's played out across America during Covid-19: Loved ones suddenly struck down and separated by illness. Jobs lost in the economic downturn. Unpaid bills piling up, despite a pledge from President Donald Trump to protect the uninsured from coronavirus costs.

Nathan Nathan and his wife Neibwen Naisher, who passed away from Covid-19 in April. (Courtesy Nathan Nathan)

But Nathan isn't American. He and his family are from the Marshall Islands—among the thousands who fled the atolls in the Pacific after U.S. nuclear testing riddled the islands with radiation and rendered their communities unsafe. The islanders' experience during the pandemic has been a tragedy inside a tragedy, the culmination of decades-old U.S. policies and public health failures that continue to chase the Marshallese.

The United States nuked their homeland. Ruined their food supply. Then promised them free health care through Medicaid before Congress later yanked it away. Now, it's given them coronavirus—at a far greater rate than the general U.S. population, and infinitely higher than their troubled home islands, where local Covid-19 transmission is nonexistent. One outbreak in a Marshallese community in Arkansas was so bad, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention this summer dispatched a team to specifically study it.

Some Marshallese in America say that because the virus ran so aggressively through their communities, they've been stigmatized as carriers of Covid-19, making it harder to find new jobs or get back work they've lost.

In Iowa and other states around the country, local leaders have tried to put a spotlight on the burdens of the Marshallese, arguing that the United States owes the islanders because of a unique international agreement known as the Compact of Free Association, or COFA. In Washington, D.C., a growing number of lawmakers have signed on to bills trying to restore the islanders' lost Medicaid coverage. And across the country, advocates have attempted to take up collections or set aside new funds, although they haven't always found their way into the neediest hands.

But as the coronavirus pandemic rages across the United States, it has hammered the Marshallese—with mounting deaths, debts and other complications. And health experts who’ve worked with the islanders argue they’ve suffered more than any other racial or ethnic group.

"We knew Covid was going to hit them hard," said Suzie Stroud, a Dubuque social worker who has specialized in working with the Marshallese. "It just brought to light all of the problems we had been fighting all along."

‘Most vulnerable’

Nearly a year into the pandemic, we're still learning about Covid-19—including why many people shrug off their infections with no symptoms, and why others will rapidly decline and even die within a few days. But epidemiologists and public health workers have concluded that there are some people and populations that are at elevated risk: the sick, the old, the obese. They've also zeroed in on how the virus is transmitted, warning against what are known as "congregate settings," where people spend considerable time indoors together.

And if Covid-19 itself could draw up ideal victims, the Marshallese would be at the top of the virus' list.

Pictures hang on a wall showcasing members of the Marshallese community now living in Dubuque, Iowa. | M. Scott Mahaskey / POLITICO

"They're definitely among the most vulnerable populations," said Tim Halliday, a University of Hawaii professor who's studied the Marshallese and other islanders covered by COFA.

For instance, the islanders disproportionately suffer from preexisting conditions, like kidney disease and obesity, that the CDC has warned are linked to more serious Covid-19 cases. One 2016 study of several hundred Marshallese in Arkansas found that nearly 62 percent were obese, about 41 percent suffered from hypertension and 38 percent had diabetes—all risk factors for coronavirus complications.

The Marshallese also tend to live in multigenerational households—mixing young and old, often in cramped quarters—and frequently gather with friends and neighbors for large, traditional celebrations. Those are ideal conditions for the virus to easily take hold and spread, CDC has concluded.

"They have a huge amount of health issues to begin with, plus the housing situation," said Halliday, the Hawaii professor. "You put just these two things together, it's a recipe for contagion—and the cases are going to be a hell of a lot more severe, because of the prevalence of other conditions."

But the Marshallese face additional challenges, too. Many islanders don't speak fluent English—a particular problem in the early days of the pandemic, when the risks of Covid-19 weren't always well-communicated to non-native speakers. Strategies like "social distancing" were hard to understand in a culture built around church and social gatherings. Subsequent paperwork and health care bills, already confusing to many Americans, have proved confounding to islanders.

Meanwhile, Marshallese flocking to the United States often ended up working factory jobs across the Midwest or South, prized for their unique immigration status; as citizens of another country, it's easier to hire them than people with green cards. But that meant many islanders remained in jobs during the pandemic where they couldn't socially distance or were deemed an essential worker at facilities that stayed open, like meatpacking plants. And the plants themselves have been repeatedly dinged by investigators and watchdogs during the pandemic, with warnings that they weren't doing enough to protect their staff.

The islanders also tend to be leery of the U.S. health system, a fear that dates back decades and is shaped by traumatic encounters with America—most notably, when the U.S. military used the Marshall Islands as a testing site for dozens of nuclear bombs in the 1940s and ’50s.

Inhabitants of the islands "are now suffering in various degrees from ‘lowering of blood count,’ burns, nausea and the falling off of hair from the head, and whose complete recovery no one can promise with any certainty," the Marshallese wrote to the United Nations in April 1954, after one particularly devastating explosion, petitioning for international help and protection.

“The United States Government is very sorry indeed that some inhabitants of the Marshall Islands apparently have suffered ill effects from the recent thermonuclear tests,” Henry Cabot Lodge, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, responded in a statement a few weeks later. “I am informed that there is no medical reason to expect any permanent after effects on their general health, due to the falling of radioactive materials.”

The U.S. government's blithe assessments were wrong: The testing left major swathes of the island chain irradiated, at levels that rival or exceed Chernobyl, and led to decades of the Marshallese complaining about ruined crops, unusual birth defects and additional cancers. It also sparked years of negotiations over compensation, with the U.S. military keen to keep a foothold on the islands as a perch in the Pacific.

Under the COFA agreement that was hammered out between the islands and the United States in the 1980s, the Marshallese gained special rights to live in America as noncitizens, pay taxes and qualify for government programs like Medicaid, the health insurance program for low-income people. About 100,000 Marshallese and other islanders covered by COFA, including citizens of Palau and Micronesia, have since relocated to the United States, government officials estimate.

But the U.S. Congress in 1996 stripped the islanders' access to Medicaid as part of a welfare reform package—a tiny legislative oversight, officials say, but one with outsize consequences for the tens of thousands of Marshallese living in America and covered by the compact. And because the Marshallese largely can't vote, and they're technically citizens of a foreign country with no congressional representation, the islanders have been stymied in two decades of attempts to have their Medicaid access restored.

Residents of the Marshallese community in Dubuque wait out the rain in hopes of hosting an annual community hog roast October 5, 2019 in Dubuque, Iowa. | M. Scott Mahaskey / POLITICO

Halliday, the Hawaii professor, warned in July that years-old decisions to strip the islanders of Medicaid access were further putting them in peril during the pandemic, writing that "many cases of COVID19 might go undetected in this community due to a reluctance to seek out care" because of the added cost and that the islanders were disproportionately uninsured.

"COFA migrants may be the least healthy of any ethnic group in the United States," Halliday added.

And taken together, that's likely why the coronavirus pandemic crept up, and then stole into so many lives all at once, hitting the Marshallese early and often.

In Spokane County, Wash., the Marshallese represent just 1 percent of the local population—but by late June, about one-third of all coronavirus cases. In Hawaii, the Marshallese and other non-native islanders were more than twice as likely as other groups to be killed or hospitalized by the virus, state health officials found last month.

One Marshallese outbreak in Northwest Arkansas was so severe that local health officials appealed to the CDC, which sent in a team of scientists this summer. The CDC's finding: The local Marshallese were more than 71 times more likely to be infected by Covid-19 than the white population, 96 times more likely to be hospitalized and 65 times more likely to die.

The outbreak numbers in the islander community "were staggering," said Katherine Center, a CDC scientist who was the lead author of the agency's report.

Center and her colleagues also uncovered a depressing duality. While the Marshallese told CDC scientists in interviews that "the costs of medical bills and lack of insurance through their employers have many of them feeling they cannot afford to seek care when they are sick," according to the agency's report, many islanders also felt they couldn't afford to skip work. As a result, the Marshallese of Northwest Arkansas kept trudging to their jobs through the early days of the pandemic, often at factories and meatpacking plants that the government kept open.

"They felt they needed to work to pay their bills," Center explained. "They were worried about basic necessities and keeping their families alive."

Pearl McElfish, the vice chancellor of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, who’s studied the Marshallese for years, highlighted the islanders’ lack of Medicaid access—which she called “a gigantic problem leaving them vulnerable to infection and death.”

“My ultimate goal in life before I die is that we get Medicaid restored for Marshallese and that we improve health equity,” McElfish added.

Had the Marshallese merely stayed on their troubled home islands, which imposed strict travel restrictions and other measures, they would have at least escaped the pandemic. The islands have remained virus-free for most of 2020, a rare public health achievement that was only interrupted in October when a worker deployed to the local U.S. military base tested positive after arriving from Hawaii.

A deadly funeral

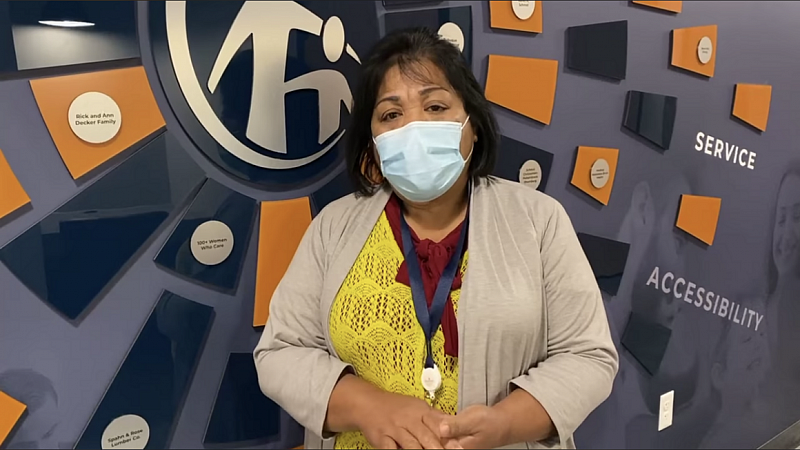

Back in Dubuque, at the end of October, I met up with 62-year-old Maitha Jolet outside of Crescent Health Care, a health center that serves hundreds of Marshallese in the city. Jolet is a leader in the local Marshallese community, and one of its loudest voices—he got some attention after telling POLITICO that the United States doesn't see the islanders as "human beings" in a story that ran in January 2020—and he's also an adviser to Crescent's long-running project dedicated to helping Pacific Islanders.

But we're talking today about his own care: Jolet's a Covid-19 survivor, one of dozens of local Marshallese who contracted the virus as it raced through his community in April and May. Before that, coronavirus had been mostly a whisper in Dubuque—a plague that struck places like China and New York City, but not this corner of Iowa, nestled between Wisconsin and Illinois.

Maitha Jolet uses a livestream from his hospital room to warn family and friends of his community about the risks of COVID-19 after contracting the disease himself. He later recovered. (Courtesy Maitha Jolet)

"This thing surprised everybody," Jolet said. "All of a sudden, everybody gets sick and hospitalized."

Jolet's done some amateur detective work, and he's convinced that he was exposed in the nearby city of Waterloo, after attending the late April funeral of Helen Kobaia, a fellow émigré from the Marshall Islands. At the time, Jolet was trying to manage his risk and cut down on travel—and he idly wondered if his old friend Kobaia, who was nearly 74, had died of this still-mysterious disease—but Kobaia's relatives made a personal appeal.

"They called and asked me to go there and join them, be part of the family," Jolet said. "I was scared. But I had no choice. It's part of our customs if someone's really close to you. … It's really hard to ignore this kind of tradition."

So on April 24, Jolet made the 90-minute drive to Waterloo with his sister-in-law and her husband. They sat in the chapel at the funeral home, with about a dozen other people. They prayed with Kobaia's family. They helped bury her.

And then they drove back to Dubuque—unknowingly bringing the virus with them, Jolet believes. All three would soon get sick. Eleven days after Kobaia's funeral, it was now Jolet who was seriously ill and needed to be admitted to a local hospital, MercyOne. He'd end up spending most of May isolated in a hospital room and needing oxygen, including a week in the ICU, before being discharged with an oxygen tank that he'd use for days.

As a result, parts of the spring are a blur, and Jolet has to keep apologizing in our conversation to say that there's a lot he missed or doesn't remember, although he can't forget how Covid-19 cut a swath through his friends and family. "A lot of Marshallese were exposed during that time," Jolet says.

Six months later, the effects of his illness don't slow him much anymore; the husky Jolet has little problem carrying a conversation as we walk laps around Crescent's parking lot, breathing through masks. He tells me that he quit one of his two jobs, providing security at a local casino, worried that he'd be around too many people in a closed, high-traffic environment, and that the hours were taxing his health. He's kept the other job, as a paraprofessional at a local school, but the financial balancing act in his house is trickier than ever.

"I'm lucky," Jolet said. "I'm doing good right now."

‘Tsunami of horror’

Inside Crescent, health workers perk up to hear about Jolet's improving health—but say they're crushed by how many more Marshallese continue to be sickened or killed by the virus, citing public reports that dozens fell ill. (They declined to share specific data about their patients, citing health care protections.) For staff working with the islanders, 2020 turned into the culmination of fears that emerged almost a year ago.

"We started to see this tsunami of horror coming our way," said Gary Collins, the health center's head. "And we knew the Pacific Islanders were going to be impacted."

Crescent has been transformed since I was last here a year ago—it's moved from a sleepy building once used as a casket factory into this sleek, brand-new facility across the street. It's added features like a test kitchen where islanders can learn how to make healthy meals and built out an entire suite to help them handle paperwork and other needs that go beyond care.

The view from the current offices of Crescent Community Health Center to its old location, a historic warehouse building once used to build caskets, shown Oct. 3, 2019 in Dubuque, Iowa. | M. Scott Mahaskey / POLITICO

And during the pandemic, Crescent has adopted new protective protocols; all visitors must undergo rigorous screening in the parking lot before they're allowed indoors. The center's gone from feeling like a community hangout last winter—boxes of free hand-me-down sweaters in the lobby, an activity messaging board, people milling about—to a much more controlled, spartan environment this season, reflecting the grim nature of the outbreak.

Serving the islanders isn't Crescent's only goal—the Marshallese represent just a fraction of their patients, at most 10 percent—but helping them is clearly a huge part of the center's intention and even facility design. Signage and Covid-19 instructions throughout the facility are in English, Spanish and Marshallese. On the third and fourth floors, a huge mural includes a photo of Sister Helen Huewe, who passed away in January after spending her final years fighting for aid to the islanders.

"I wanted it to be honorable for Sister Helen to still be looking over us," said Collins, the center's CEO. "I wanted her to know that we are taking care of the Pacific Islanders."

Collins' staff describe him as a kind, organized leader—someone who immediately sorts and alphabetizes incoming email. One of those email folders is dedicated to Covid-19, with about three-dozen subfolders, ranging from topics like "dental updates" to "strike force testing" and, of course, "Pacific Islanders and Marshallese." And that sort of practical, proactive ethic has infused the center, which began in February to try to combat a mystery virus that still seemed like a far-off threat from Southeast Iowa.

Drawing on the available scientific literature—which at the time, was mostly limited to findings from China, shared by organizations like the CDC and the World Health Organization—Crescent's team built a formula to identify the center's highest-risk patients for Covid-19, assigning them "points" based on factors like their age or whether they had diabetes or hypertension. Ultimately, they narrowed the list down to about 100 patients, which included several dozen Marshallese.

"We just started calling them, and we said, 'Hey, we think this is coming, and we are going to give you a three-month supply of all your medications,'" said Heather Rickertsen, who leads Crescent's pharmacy efforts.

"'Please stay home. Please don't go out. Please don't go to the pharmacy. Don't go to the hospital,'" Rickertsen said she and her colleagues told the patients. "'Don't know if you need something? Call us but don't come in because we don't know enough about this disease to know what to do.'"

The center also teamed up with other Dubuque leaders and civic organizations, like a project to develop shelters for the Marshallese and other locals who might have been exposed to Covid-19 and needed a place to safely self-isolate. The need was particularly acute given the crowded homes of many Marshallese, Crescent staff said.

"We had found that about two paychecks were supporting between 10 to 12 people" in each household, says Stroud, the social worker, who helped lead Crescent's Marshallese project for almost three years before leaving last month.

"And the space they can afford to live in were usually places with one bathroom," Stroud added. "So if someone got sick, they couldn't isolate—there would be up to a dozen people needing to use the bathroom, too. And they wouldn't have their own bedroom."

And as people started to get sick, Rickertsen and her team came up with "COVID care packages" that contained crucial supplies, like pulse oximeters to measure a person's oxygen level and rescue inhalers, which could be safely dropped off.

But ultimately, it wasn't enough.

"We can't lock people in their houses. We can only give guidance," Collins said. "People are going to comply or they're not."

And April was the tipping point. The virus began raging through the local meatpacking plants. Marshallese residents, like Jolet, were falling seriously ill at gatherings. Others, like Nathan and his 19-year-old daughter, tested positive but didn't need hospital care.

"The ICUs are full of us," Irene Maun Sigrah, Crescent's Marshallese translator, told a local newspaper in early May, warning that Covid-19 was running amok in her community. Sigrah would know: She, her husband and her two children were among those who contracted it.

By mid-June, at least eight Marshallese in Dubuque had died of Covid-19, officials said, an outsize blow in a community that numbers just 800 people.

"Those first three months for the Pacific Islanders—April, May, June—were just tragic," Rickertsen said.

The uneven impact on the Marshallese got the attention of Dubuque's local leaders, and a parade of officials—from the mayor to Crescent's executives—appealed directly to lawmakers like Sens. Joni Ernst and Chuck Grassley, Iowa's Republican senators, urging them to help restore the islanders' lost Medicaid. But their staff were noncommittal, a posture the senators' offices adopted in response to inquiries from POLITICO, too.

Signs outside Crescent Community Health Center warn about Covid-19 in Marshallese, English and Spanish. | Dan Diamond / POLITICO

Local leaders also took note of how the islanders were being hammered by the virus, settling on one strategy: Get them back their Medicaid. The Iowa Commission of Asian & Pacific Islander Affairs, a committee appointed by the governor, called for Iowa to seek a federal waiver that would allow the Marshallese and other COFA migrants to be covered.

"Since the onset of the pandemic this spring, Marshallese in the US [have] succumbed at higher, disproportionate rates due to underlying chronic health conditions," the commission wrote in September to Republican Gov. Kim Reynolds, appealing to her to restore the islanders' Medicaid.

The outsize burden on the Marshallese is “pretty evident,” said Ben Jung, a West Des Moines businessman who chairs the commission and said he’s hoping to meet with Reynolds’ office in January.

“There is a sense of urgency” to getting the islanders Medicaid, Jung added. “We want to provide the fullest health care that’s needed so they too can be safe as possible … like others in Iowa.”

A spokesperson for Reynolds didn't respond to a request for comment.

Rickertsen, the pharmacist, framed the islanders' lack of Medicaid as a kind of original sin for the coronavirus crisis.

"If they were able to have access to health insurance, and been able to get care and drugs, that would've improved their diabetes control," Rickertsen said. "If they were able to control their diabetes, the chances of them surviving Covid would've been better."

"I don't know it would've changed infection rates, but if they had insurance, I believe they would be better able to weather the storm of Covid-19," she adds. "It is incredibly frustrating and aggravating … to let the political nature of stuff compromise what affects patients and families."

A Washington logjam

In the nation's capital, advocates for the Marshallese share Rickertsen's anger and frustration over how Covid-19 has walloped the islanders and, particularly, how their inability to get on Medicaid likely contributed to the islanders' bad outcomes.

But after two decades of fighting—and losing—the effort to restore Medicaid access, those advocates like Juliet Choi, the CEO of the Asian American & Pacific Islander Health Forum, are expressing a new emotion: cautious optimism.

"2020 was a watershed moment," Choi says, noting that a coronavirus relief package that passed the House in May, the HEROES Act, contained legislation to reinstate the islanders' Medicaid access. That's the first time the House advanced such a bill in more than 20 attempts—a historic breakthrough in a difficult election year, Choi hastens to add.

"Given the political divide in Washington, the COFA bill in the House was a shining example of bipartisanship to do the right thing," Choi says. Notably, Republicans like Washington Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers—who's set to be the top GOP member of the powerful House Energy and Commerce Committee, which helps write health care legislation—and Arkansas Rep. Steve Womack signed on to the bill as attention on the islanders' plight grew across 2020.

But the HEROES Act never went any further as talks over coronavirus relief broke down, leaving the Medicaid-restoration effort in limbo. And for decades, attempts to restore the islanders' Medicaid access have died in the Senate, despite Hawaii lawmakers like Sens. Mazie Hirono and Brian Schatz, both Democrats, continually introducing bills every session.

There's hope that a fix to cover the islanders' Medicaid will find its way into a year-end funding package that passes this month, congressional aides say. The estimated cost: nearly $600 million over a decade, which COFA advocates argue could be neatly tucked in a bill that's likely to be $1 trillion or more.

Residents of the Marshall Island community living in Iowa take advantage of a pre-COVID food program to purchase items at a farmer’s market October 5, 2019 in Dubuque, Iowa. | M. Scott Mahaskey / POLITICO

Choi says she's trying to be pragmatic as well as optimistic, which is why her group is setting a goal for 2021: Make the Senate bill a bipartisan effort, targeting GOP lawmakers like Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski and Utah Sen. Mitt Romney, who have reputations for compromise—and islander populations living in their states. One strategy is shifting how advocates talk about the COFA issue with Republicans, focusing less on the moral argument of restoring Medicaid and more on the national security implications of working well with the Marshallese. (The Marshall Islands remain a strategic launching point for U.S. military forces in the Pacific Ocean, a fact not lost on Chinese officials, who themselves are trying to woo the Marshallese.)

Paired with the surging enthusiasm in the House, just a few more Republican votes in the Senate could make the difference to restoring the islanders' Medicaid.

But if Democrats win two seats in the Georgia Senate elections next month, allowing them to retake the chamber, Choi may not need to worry about shoring up GOP support. That's partly because Hirono has spent years pestering Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer — with the Hawaii senator joking that she brings up the Medicaid issue so often with Schumer, the top Democrat has learned to greet her by saying, “I know, I know—the COFA migrants.”

Schumer himself vows: He's on board.

“I fully support Sens. Hirono and Schatz in their push to finally restore Medicaid coverage to COFA migrants," Schumer told POLITICO. "I have continually and closely worked with them to advance this issue, and will not rest until it is signed into law."

And the Marshallese should have an ally in the White House next year. As a presidential candidate this year, Joe Biden promised to restore the islanders' access to Medicaid, with his campaign saying that Biden's health plan to boost availability of coverage would encompass the COFA migrants, too.

Meanwhile, the advocates have a wish list of other goals to help the islanders during the pandemic, like winning more support for language services to help the Marshallese navigate an often confusing health system.

"I'm just begging for our political leaders to have the political will to allocate resources—even translated materials—as our country is bracing for the next bad wave of Covid this winter," Choi says. "But the fact that we have political leaders willing to advocate to restore Medicaid, that's a really good thing."

Big bills, few answers

But the uncertain future of Washington legislation doesn't help islanders in the Iowa heartland like Nathan, who when we first spoke this winter, was facing nearly $120,000 in coronavirus-related bills for his late wife's care and increasingly urgent warnings that payments were due in just days—even though there's no conceivable way he could pay.

Money is very tight, Nathan says through an interpreter. After he lost his job as a part-time hotel employee in April, and the death of his wife just days later, he had to move in with one of his sons, who counts chips at a local casino in Dubuque, and has struggled to find steady work since. The hotel where he and his wife worked until the pandemic has given him "nothing," he added, although the manager did provide some food after the burial of Nathan's wife.

"I've gotten nothing to help out with anything," Nathan reiterates, asking me why the bills are still coming and what he should do about them.

It wasn't supposed to be this way. President Donald Trump and his aides spent the year bragging about protecting the uninsured like Nathan and his wife from Covid-19 costs. Under the CARES Act, a coronavirus rescue package that passed in March, $175 billion was set aside for what's known as the Provider Relief Fund. Health care providers were subsequently invited to apply to cover the costs of providing care for uninsured Covid-19 patients.

"When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, my Administration implemented a program to provide any individual without health-insurance coverage access to necessary COVID‑19‑related testing and treatment," Trump wrote in an executive order in October.

And here in Dubuque, the mounting bills facing the Marshallese caught the attention of local health workers, including Mark Janes, a pulmonologist who started a GoFundMe campaign in May.

"We have a population of Marshallese here who have become ill with SARS-COV-2," Janes wrote, touting the fundraiser. "They have no insurance. We are a small community and they will need help."

Irene Maun Sigrah, a Marshallese health worker at Crescent Community Health Center, records a public service announcement in November 2020 about how to stay safe from Covid-19 during the holidays. | Crescent Community Health Center

Within a week, more than 400 donors had poured in more than $25,000. Janes quickly handed off the funds to the Dubuque Foundation, a local nonprofit that could better handle donations for tax purposes.

But when I reached Nancy Van Milligen, head of the Dubuque Foundation, in December, she shared a surprising admission: The money raised for the Marshallese fund has been largely untapped.

"It's been kind of hard to give this fund away," Van Milligen said. "If anyone has a bill, they're supposed to contact us and we're supposed to take care of it … but we haven't heard anything recently."

But she also insists that the Marshallese shouldn't be getting billed at all, citing the CARES Act provision that created a fund for providers to get compensated.

"All of the health care has been free, even to the Marshallese," Van Milligen said. "The hospitals are supposed to be covering people for this care."

I press her on this, citing the case of Nathan and other local Marshallese who have spoken with me about the big bills facing their community. Van Milligan says she'll look into it, and later sends me a note saying that her hospital contacts reassured her that the islanders' care is covered.

"If a Marshallese patient is not insured, the hospital was/is able to get reimbursed by the Cares Act," she tells me in an email.

So why is Nathan getting billed for his dead wife's care? Most likely: human error. In many cases, hospitals and doctors haven't done the work to submit claims for their uninsured patients, analysts say. Or the patient was diagnosed with something other than Covid-19 as a primary diagnosis, like kidney failure, making it impossible for the provider to claim any funds from the coronavirus relief package.

By far the biggest bill Nathan has received—nearly $93,000, covering his wife's nine-day hospital stay—comes from Finley Hospital, a facility in Dubuque run by the UnityPoint health system. Identifying myself as a reporter, I repeatedly called UnityPoint to ask about the case of Nathan's wife; finally, a clerk tells me that the bill will be submitted for review, with a determination coming no earlier than mid-January.

Meanwhile, Nathan's gotten a $12,000 bill from Tri-State Dialysis, which happens to be a subsidiary of Grand River Medical Group, which separately billed Nathan's wife $14,135. After several days of email and phone calls, a billing manager at Grand River Medical Group tells me that the $26,000-plus in total charges for Nathan's wife will be covered by the CARES Act and that he doesn't have to worry about the bills anymore.

It's a vivid reminder of the roadblocks that face someone like Nathan, who doesn't speak English, and other patients who may not know what to do. For instance, the federal Health and Human Services Department has posted a public data file of all the providers that have applied for funds to cover the Covid-19-related costs of their uninsured patients. The file lists more than 27,700 individual rows, with claims filed by hospitals and medical groups all over the nation; Finley Hospital shows up twice, claiming a total of $57,428. But Grand River Medical Group isn't on there at all, suggesting that it hasn't previously applied to get compensation for its uninsured patients.

That's why it's a misnomer to say that all Covid-19 costs are being covered for the uninsured, says Karyn Schwartz, an analyst at Kaiser Family Foundation who has studied why patients like Nathan's wife keep getting billed.

"What HHS did is say we'll use this $175 billion fund, and we'll take some of the money to reimburse providers," Schwartz adds. "But it's not the same thing as health insurance, and it didn't include the protections you'd need for it to be comprehensive."

As a result, uninsured patients like Nathan's wife can still end up facing large bills—regardless of what the president proclaims or Van Milligen believed.

"This fund wasn't meant to be comprehensive," an official at the Department of Health and Human Services who worked on it tells me. "As much as I'd like to solve the uninsured problem, this fund isn't the answer."

Fighting back

After Covid-19 ravaged their community in the spring, the Marshallese of Dubuque told me they tried to dutifully observe CDC guidelines, from better social distancing to vigilance around wearing masks. That's borne out in the numbers; while the virus' impact on the Marshallese is still outsize, their share of Covid hospitalizations and deaths has fallen as the virus has surged in Iowa this fall and winter.

"They've become really diligent about Covid-19," says Stroud, the social worker who works with the Marshallese. "They know better than anyone how dangerous coronavirus can be."

But try as they might, the islanders can't escape the virus. As I was writing this story, one more member of the Marshallese community of Dubuque passed away—a 41-year-old that I'll call J., who suddenly died in November. Multiple friends of J. told me his death was due to Covid-19. (Through a friend, J.'s family declined comment.)

J. let me shadow him last year, as I followed his pricey health care treatment and Crescent staff's attempt to stabilize his vitals and get him health coverage. Suffering from kidney failure, with a wide smile that didn't suffer despite his lack of teeth, he'd become somewhat of a project for the team; his English was spotty, but his enthusiasm didn't need any translation. Later I realized that we'd likely crossed paths without knowing it—the chic restaurant near my hotel, where I had dinner at the bar several nights in a row last year, was also where J. worked as a dishwasher in the back.

Rickertsen says she can't comment on specific patients, citing medical confidentiality. But as she describes one loss that stuck with her, I realize she's describing J.—all the ways that Crescent staff tried to help him, until he was struck down in the fall wave of Covid-19 that swept through Iowa.

"For me, that was probably the hardest time," Rickertsen said. "After that happened, I literally laid in bed all weekend. I was like, [to my husband], I can't even get out. I can't deal with this."

The scars linger for the Marshallese too, who say they've been stigmatized ever since the wave of coronavirus swept over their community this spring—and the local news coverage that resulted.

Before coronavirus arrived, Irene Maun Sigrah, a health worker focused on the care of Pacific Islanders living in America, left, assists Maitha Jolet during an annual community hog roast October 5, 2019 in Dubuque, Iowa. | M. Scott Mahaskey / POLITICO

When we were speaking in October, Jolet said he was shocked when he tried to buy a hog from the farmer who'd been supplying him with hogs for years, a man whom he thought had become a family friend.

"Last month, I called him to buy a hog—and he said, no Marshallese are allowed at my farm," Jolet said. "I said, ‘Hey man, that's really discrimination. You're trying to discriminate.’"

Jolet says he's upset by the perception that the Marshallese are somehow coronavirus carriers.

"We didn't invite the Covid to us," Jolet adds, his voice rising in pitch. "Covid, it just came to us."

Nathan, meanwhile, says he's grieving after a year when he lost his job, his home and, most importantly, his wife.

"She's the only woman in my life," he says through an interpreter. "I really miss her."

It took weeks to set up our interview, and as we wrap up, I asked Nathan why he eventually decided to talk to me.

"I want to tell the world about the Marshallese people who came to the United States, seeking a better life—and got limited access to health care instead," Nathan says. "I'm worried this will impact a lot of other Marshallese too."

This story was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism National Fellowship and its Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

[This story was originally published by Politico.]