In LA Jails, mentally ill people are chained to tables and rarely get psychiatric care

This story was originally published in The Appeal with support from the 2022 Data Fellowship.

Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department

This piece is part of a series of stories on the increasing number of people with mental illness imprisoned in Los Angeles County jails. To read the first piece in the series, click here.

During the few hours that people with mental illness are allowed out of their cells in the Los Angeles County jail system’s high observation housing, they are shackled to tables. Some don’t have real clothing—just tear-resistant suicide gowns to prevent them from harming themselves. Others smear feces on the walls of their cells. Flooded toilets are a regular occurrence. People scream and pace back and forth. Cells overflow with garbage. In certain housing units, mesh screens line the railings of the upper levels to prevent people from jumping.

This is what thousands of people endure every single day in Los Angeles, where an average of 5,700 people with mental illnesses were incarcerated in 2022, according to data from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD), which oversees the jail system. Many of those people are held in the Twin Towers Correctional Facility, which has been called the largest mental health institution in the country. But many of the people inside are not getting the treatment they need, according to reports from local and federal watchdogs and experts who spoke with The Appeal.

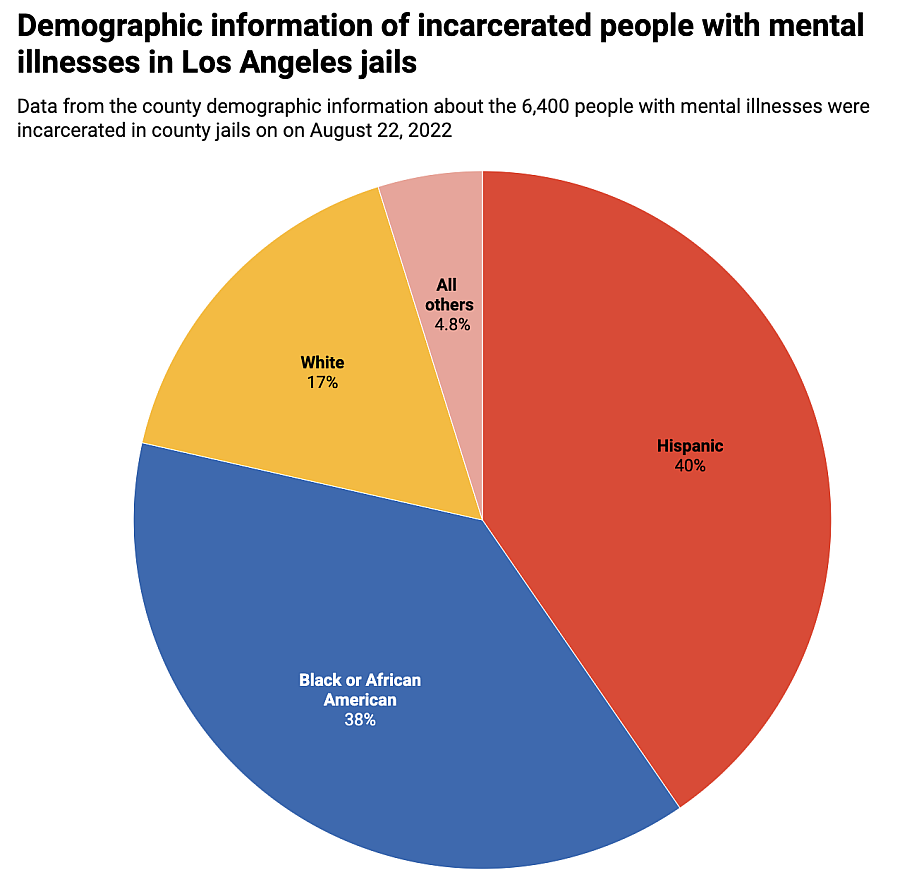

Data obtained by The Appeal from the county’s Department of Health Services (DHS) shows that on Aug. 10, 2022, about 6,400 people with mental illnesses were imprisoned in county jails—most of them people of color. As of that date, at least 4,500 people were considered so mentally unwell and likely to harm themselves that they needed to be checked on at least every 30 minutes or less.

The number of people with mental illness inside the jail system has skyrocketed over the past decade, according to data from the LASD. Roughly 2,500 more people with mental illnesses are locked up in county jails today compared to 10 years ago, despite the fact that in 2015 the county created an Office of Diversion and Reentry (ODR) to reduce the number of people with mental illness trapped in jail.

In October, the Office of Inspector General (OIG), a county agency tasked with overseeing the jails, filed a report stating that the steady increase of people arrested with mental health needs has filled housing units to capacity. When the housing units are full, the report states, “new patients who present with moderate or severe mental illnesses—some of whom are tethered throughout the entire intake process—are required to remain in the Inmate Reception Center” or the central booking location until housing becomes available. Overall, the report says that between 2019 and 2022, the sheriff’s department implemented only seven out of the 111 reforms the OIG recommended during that same time period.

In 2015, the Department of Justice put the Los Angeles jail system under a mandatory federal monitoring program, which required that LASD address inadequate mental healthcare and excessive force by guards inside the jails. Nicholas E. Mitchell, the independent monitor enforcing the DOJ’s federal consent decree, said last fall that the county still had not met basic benchmarks for humane treatment more than seven years after the DOJ mandated reforms. A report Mitchell authored in September 2022 states that the county was not providing meaningful group therapy to incarcerated people and that some of the most severely ill people were not getting required out-of-cell time.

In February, the county asked to push back deadlines for meeting certain federal requirements by three years. In a scathing response filed Feb. 27, attorneys for the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division condemned the county for allowing conditions in the jails to reach a crisis level.

“That there is a mental health crisis in the Jails is undisputed: Suicides are spiking, hundreds of individuals wait weeks for mental health housing, and only a fraction of the nearly 200 individuals who require psychiatric inpatient care at any given time can access it,” the Department of Justice wrote. “Those who require high-observation mental health housing (HOH) wait weeks in near-total isolation to move to such specialized housing. Should they eventually arrive at HOH, these individuals receive virtually no out-of-cell time, either for recreation or treatment. Under these conditions, individuals decompensate, strip naked, smear feces, and physically hurt themselves.”

On the same day the DOJ excoriated the county, the American Civil Liberties Union also filed a motion asking a federal judge to hold Los Angeles County, the Board of Supervisors—the county’s highest governing body—and the sheriff in contempt of court for failing to fix the abhorrent conditions inside county jails.

Attorneys, community activists, and mental health experts who spoke with The Appeal said that people are not getting adequate treatment inside the jails and questioned whether it is possible to treat mental illnesses inside jail at all.

“Effective therapy cannot happen in jail, because jail is a traumatic experience inherently,” said Liz Sutton, a licensed clinical social worker who runs a program that helps get incarcerated people with mental health needs released into outpatient care. “Any sort of support groups they might be doing, it’s not helping. It’s a Band-Aid on a bullet wound. It’s not possible to do anything there.”

Sutton said she receives packets of information on incarcerated people entering the program she manages. The packets contain information on what treatment people received in jail. Sutton said the packets often show that incarcerated people receive life-skills training, like how to make a budget, but rarely, if ever, therapy or similar services, like Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.

A 2020 report by the RAND Corporation estimated that more than 60 percent of people incarcerated with mental health issues—at least 3,300 people—could be diverted from jail. Advocates say there is a simple solution to the county’s capacity problem: move people out of the jails and into treatment.

“Treatment in the jails is not effective,” said Ivette Alé-Ferlito, executive director of La Defensa, an intersectional feminist organization that works to divert funding out of the criminal legal system and implement alternatives to incarceration. “Those dollars go a much longer way in providing care outside of the jails. We’re talking about folks going in traumatized, going in with mental health needs, that are only retraumatized once they’re inside. This is a threat to their health.”

In a statement emailed to The Appeal, a spokesperson for Los Angeles County said that officials are committed to reducing the jail population, improving conditions inside the jails, and providing a higher quality of care for incarcerated people.

The spokesperson said it is challenging to safely provide structured out-of-cell time to people who are experiencing severe mental illness and listed several actions the county is taking to address these concerns. These include appointing a DOJ compliance officer to comply with the conditions of the consent decree, taking steps to increase mental health and jail staff, expanding mental health treatment resources at the county’s Pitchess Detention Center, and investing in community-based mental health care to reduce the number of people with mental health conditions who become incarcerated.

“The County is fully committed to a higher quality of care for those who must remain in custody,” the spokesperson said, “but it needs the authority and collaboration of the courts to reduce the jail population by permanently changing the rules around cash bail, increasing diversions to community-based programs, and giving the Sheriff’s Department more flexibility in releasing individuals from custody when appropriate.”

Department of Health Services (DHS) data reveals insights about the thousands of people with mental illness locked in Los Angeles County jails every day.

Nearly 85 percent of people with mental illness in Los Angeles jails are men. The data only lists two genders, male and female, and does not capture the full spectrum of gender identities.

About 40 percent of incarcerated people with mental illnesses in Los Angeles County are Hispanic. Nearly seventeen percent are white. Thirty-eight percent are Black, despite the fact that only 9 percent of county residents identify as Black, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Chart: Meg O'Connor

Source: Los Angeles County Department of Health Services Get the data Created with Datawrapper

Roughly 80 percent of people are listed as between the ages of 26 and 59. But the data becomes more specific for younger people. Nearly 800 people were aged 21 to 25. Another 116 people were 19 or 20 years old. Twenty-six teenagers aged 16 to 18 with mental illnesses were incarcerated in Los Angeles on Aug. 10, 2022.

Most people with mental illnesses in Los Angeles jails are held in the Twin Towers Correctional Facility, a massive, windowless building complex that houses more than 2,600 mentally ill people.

Nearly 1,500 others are incarcerated in Men’s Central Jail, a dangerous and decrepit facility that county officials have vowed to close. A court-appointed monitor has called the conditions in Men’s Central Jail “deplorable” and stated that during a 2021 site visit, the cells were “poorly lit” and “overflowing with garbage.”

Both Twin Towers and Men’s Central Jail are over capacity. A 2015 report on jail conditions by the Health Management Associates, a consulting firm, stated that both facilities “have structural designs that complicate the ability of correctional staff to provide a safe and secure environment, interfere with the staffs’ ability to clinically monitor the status of the patient-inmate population, and create barriers that complicate the ability to meet the health care service needs of the individuals housed in these facilities.”

Los Angeles County has held some people in these conditions for more than two decades. According to the DHS data, five people with mental illness have been incarcerated since 2000. Another 126 people with mental illness have been incarcerated for five to ten years. A majority of those detained in county jails—over 60 percent—were incarcerated more recently, in 2022. California jails hold both people awaiting trial and people serving full prison sentences post-conviction. Yet jails, which are designed for short-term, pretrial stays, typically do not have the same types of programming and facilities—like classrooms—as prisons.

“That members of our community could be locked up for years under the supervision of one of the most deadly, scandal-plagued Sheriff’s departments in the nation should deeply alarm the public,” said Brian Kaneda, deputy director of Californians United for a Responsible Budget, a statewide organization committed to shifting state spending on incarceration toward things that prevent people from interacting with the criminal legal system in the first place, such as housing, healthcare, and jobs.

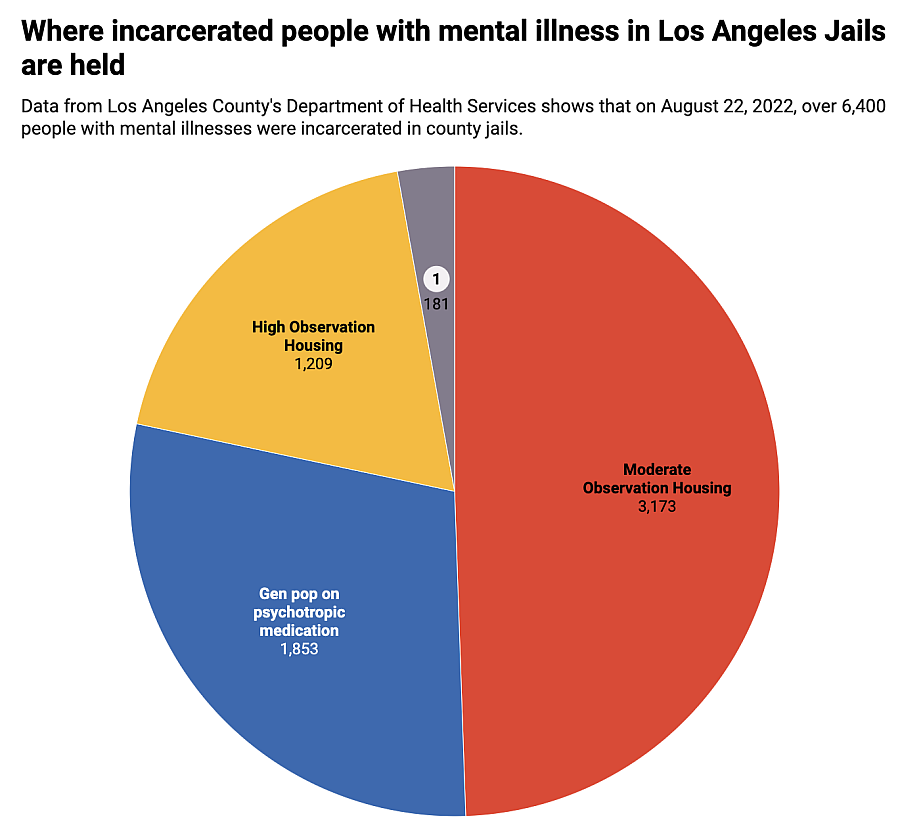

The data also reveals the level of care people in the jails are receiving. Almost one-third are in the jail system’s general population and on psychotropic medication, meaning they are receiving medication to treat mental illnesses but remain housed with the rest of the incarcerated people.

Chart: Meg O'Connor

Source: Los Angeles County Department of Health Services Get the data Created with Datawrapper

About half of incarcerated people are in moderate observation housing, which means that they are considered ill enough that jail staff are supposed to conduct safety checks on them every 30 minutes. According to a 2021 report from the court-appointed monitor, people in moderate observation housing have mood instability, psychotic symptoms managed by medication, and pervasive patterns of self-injury. Moderate observation units have mesh screens along the railings of the upper levels to prevent people from jumping.

Nearly one-fifth of incarcerated people are in what the jail system calls “high observation housing,” meaning they are considered significantly impaired and require safety checks every 15 minutes. People in this level of care are given suicide-resistant blankets, gowns, and mattresses. The more than 1,200 people in high observation housing are considered some of “the sickest patients in the Department’s care,” according to a 2021 report from the court-appointed monitor. The county says people held at this level are largely unable to communicate and are in persistent danger of hurting themselves.

When monitors visited the jails in 2021, they said that they “observed no therapeutic group programming being offered” to people in high observation housing and saw people handcuffed to individual metal tables in the shared dayroom for their required out-of-cell time. Those who remained inside the cells were generally sleeping, pacing, or awake but unresponsive.

Almost 200 people are designated as needing the department’s highest level of care—the forensic inpatient unit. These people suffer from severe, debilitating symptoms and require safety checks every 15 minutes. Court-appointed monitors say that people in the forensic inpatient unit have more out-of-cell time than people in high observation housing. But space in the forensic inpatient unit is extremely limited and people who need this higher level of care are often left waiting in high observation housing. According to a motion the county filed in federal court last month, there are currently 124 people on a waitlist for forensic inpatient care.

“Patients requiring [forensic inpatient] level of care may display symptoms such as smearing or throwing feces, banging one’s head against the cell door, not eating or drinking, severe self-mutilation, and suicidal and/or homicidal behaviors,” a 2018 report from the county OIG states. But because forensic inpatient beds are so limited, correctional staff “face daily decisions about which, if any, [forensic inpatient] patients have stabilized just enough to discharge in order to admit another, even more acute and endangered patient.”

This cycle puts both staff and incarcerated people at risk. The report states that staff members in the high observation housing unit are “frequently assaulted with feces, urine, and other bodily fluids” and sometimes physically extract people from their cells, which can further traumatize incarcerated people.

“A man told me he was in suicide watch, came off, and didn’t see a doctor for a month,” said Mark-Anthony Clayton-Johnson, the executive director of Dignity and Power Now, a grassroots organization that supports incarcerated people and their loved ones. Clayton-Johnson also inspects the jails in his capacity as a member of the Sybil Brand Commission, another county agency that monitors local incarceration facilities.

“We’ve seen people’s cells smeared with feces—that person is on a waiting list to get a bed in the more intensive observation section,” Clayton-Johnson said. “He is number 34 on a list of over 100 people. He’s been on it for a month. Men’s Central Jail is a dungeon. It is inhumane and it needs to be closed. But now we’re moving people with very serious needs into there because we don’t have places to get them out.”

The most recent federal monitor’s report noted the county is still not complying with several of the requirements from the 2015 settlement agreement. On Feb. 17, the county proposed “alternative timelines” for satisfying the requirements it was told to meet more than seven years ago.

In the filing, the county argued it has made significant improvements since the DOJ began monitoring the jail system. The county argued that the current timeline—which, among other requirements, orders the county to provide ten hours of unstructured out-of-cell time and ten hours of therapeutic or programmed time per week to people with mental illness by June 2024—is arbitrary and unrealistic.

Instead, the county proposed what it called a “sensible” timeline that kicks the deadline for complying with the DOJ mandates to July 2026. A federal judge has yet to decide whether to grant the county’s request for an extended timeline.

The county called this proposed timeline “aggressive” and said that it requires expanding the number of beds available for non-jail diversion programs to “at least 3,700.” The county had an opportunity to hit that number last summer, when Supervisor Holly Mitchell filed a motion to find funding to expand the ODR’s capacity by 3,600 beds.

The ODR takes people experiencing mental illness, substance use issues, or houselessness out of jail and connects them with permanent supportive housing, case management services, and treatment. The office has been extremely successful: One 2019 report by the RAND Corporation found that of a group of 96 participants, 74 percent remained stably housed after one year and 87 percent had no new felony convictions.

But the county ignored Mitchell’s motion and instead chose in October to expand ODR by only 750 beds, bringing ODR’s total capacity to nearly 3,000 beds.

In a statement shared with The Appeal, the spokesperson for Los Angeles County defended the work officials have done to expand ODR so far.

“That 750-bed expansion is the largest in ODR’s history, and it is estimated it will take until December 2024 to fully utilize those beds,” a spokesperson said. “That’s because the County does not have the authority to unilaterally release people from jail; that requires court action. In the meantime, we are not standing still.”

The county noted that it significantly increased ODR’s budget last year and said ODR is just one of many tools the county is using to advance its “Care First, Jails Last” agenda. But advocates say that the county has yet to act with the urgency needed to address the crisis in the jail system.

“The time for tinkering at the margins is over. We are in a state of crisis,” said Alé-Ferlito of La Defensa. “The answers are in plain sight for the county.”