Legislation caps momentous year in battle against valley fever

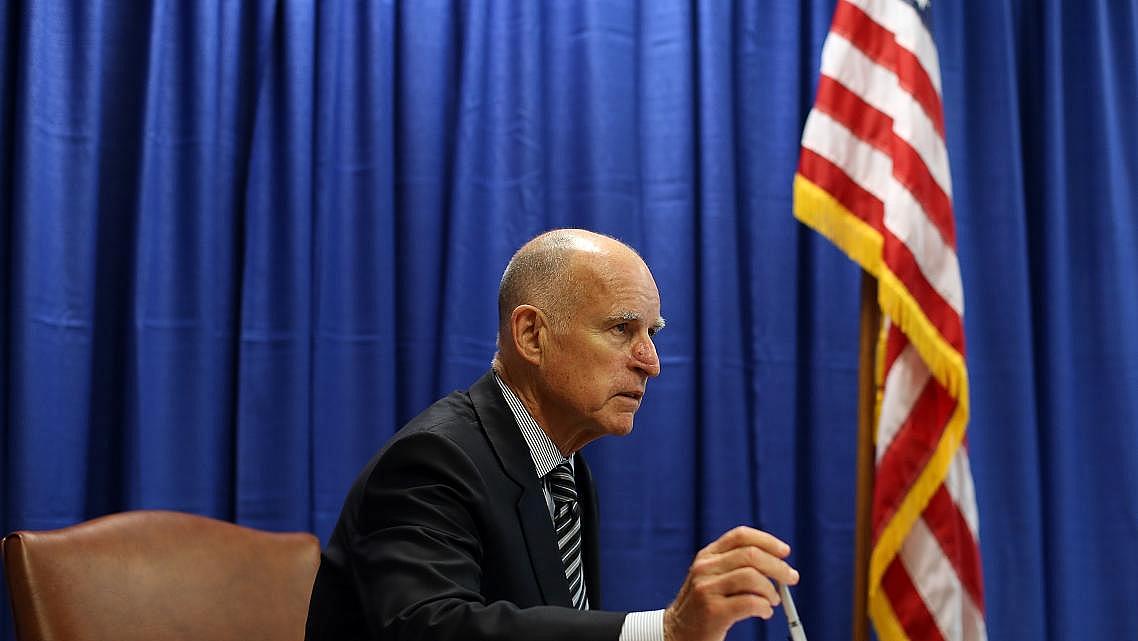

Gov. Jerry Brown signed into law another California bill targeting valley fever Monday, capping a momentous year for the regional disease long overlooked by lawmakers.

“It’s been a great, great year for families and Californians affected by valley fever,” said Assemblyman Rudy Salas (D-Bakersfield), who led the charge on a series of bills and a boost in funding for the fungal illness. The disease is caused by the Coccidiodes fungus, which grows in the soil of the Southwestern United States and plagues thousands of Californians and Arizonans annually.

One recently signed measure – Assembly Bill 1790 – seeks to improve public and health care providers’ awareness of the disease’s symptoms, treatment and diagnosis. In August, Gov. Jerry Brown signed into law two other valley fever bills that aim to remedy flaws in disease reporting brought to light by the Center for Health Journalism Collaborative’s “Just One Breath” series.

Efforts to combat the disease also are gaining traction on the federal level. House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) recently introduced legislation that would strengthen valley fever research and vaccine development. Along with those legislative strides, California’s 2018-19 state budget earmarks $8 million to address valley fever through research and outreach.

“It is a thrill to see the focus on finding new ways to deal with the disease,” said Sandra Larson, a member of the Valley Fever Americas Foundation. “New diagnostic tests, better reporting, more awareness – all these things will help us in the fight to conquer Cocci.”

Legislation takes aim at disease reporting problems

Last month, Brown signed into law two bills targeting problems with how the disease is reported. Supporters hope that the two bills will lead to better surveillance of the disease, which has historically been grossly underreported.

“Once we show the numbers, we can dedicate the resources it deserves,” Salas said.

Specifically, AB 1787 establishes an annual deadline for the California Department of Public Health to tally the number of valley fever cases across the state and notify local health departments of changes to case counts, which can happen if a patient has already been counted elsewhere.

That annual deadline and timely feedback means that everyone has the same data at the same time, ensuring consistency. The state will also notify the counties throughout the year if there is a duplicate case so that they can adjust accordingly.

“Having a set deadline helps keep the data more consistent so we know we’re analyzing the same things,” said Kim Hernandez, Kern County’s epidemiology manager.

AB 1788 allows for the use of highly-reliable lab results alone to confirm a valley fever diagnosis. Previously, some counties in California used a two-step confirmation process of lab results and a patient’s clinical information. That extra step of confirming the clinical information led to delays and potential cases not being counted.

“It’s a lot of manpower to go and track down every person,” Hernandez said. “It’s highly likely that people who live in an endemic area with a positive lab result do have it.”

The bill awaiting the governor’s signature (AB 1790) is intended to raise awareness of the disease among local health departments, health care providers and the public. About $2 million of the state budget funding will fuel this outreach effort. The remaining $6 million will fund research and be divided between the University of California and the Kern County-based Valley Fever Institute.

The stars aligned this year

Back in January, Rob Purdie, the vice president of the nonprofit Valley Fever Americas Foundation, remembered thinking that 2018 was the year that “the stars are aligned for valley fever.”

The moment wasn’t lost, something he and other stakeholders attribute in part to growing media attention, fueled by in-depth reporting from the Center for Health Journalism’s Collaborative. In 2012, the Collaborative started reporting on valley fever, bringing more widespread attention to a disease that was unknown to many outside endemic regions. In the “Just One Breath” series, the collaborative explained what happens when people breathe in the microscopic fungal spores. While some people show no symptoms, the spores wreak havoc on others, causing a lifetime of health issues or even death.

Over the past six years, the collaborative — which includes the Bakersfield Californian, Radio Bilingüe in Fresno, Valley Public Radio in Fresno and Bakersfield, Vida en el Valle in Fresno, the Voice of OC in Santa Ana, Hanford Sentinel, the Arizona Daily Star in Tucson, La Estrella de Tucsón and CenterforHealthJournalism.org — published dozens of articles on valley fever.

A collaborative team of reporters representing news outlets in California and Arizona reported in English and Spanish, for print, online and radio. They set aside competitive concerns to share reporting in order to call attention to a long overlooked epidemic, an approach praised by the Columbia Journalism Review and by the legislators who took action.

The Center for Health Journalism’s “original and informative coverage has had a significant impact and has shaped my own approach,” Salas said. “It’s been impactful because it’s made a change in policy and helped families up and down the state.”

That sustained reporting has played an important role in keeping the disease on people’s minds, said Dr. John Galgiani, director of the University of Arizona Valley Fever Center for Excellence. “Repetition has its own impact,” he said. “Telling the story once, it dies. But if you keep telling it over and over again, people remember.”

But even with the legislative and financial strides taken this year, more needs to be done, Galgiani said. He called for “a paradigm shift” in which money is devoted to developing a promising treatment. “The $8 million is useful, but you’re not going to end up with a vaccine … I think it helps bring attention to the problem and that might bring more support.”

Last year, the number of valley fever cases in highly endemic Kern County increased for the fourth straight year, including nine deaths that year alone. Statewide, 2017 saw a record high for the second year in a row, bringing the total number of cases to 7,466 — nearly 2,000 more than 2016. In 2017, Arizona reported 6,885 cases, up from 6101 the year before.