Living in a maternal care desert in Nevada: long travel times, forgoing care, high costs

The story was originally published by the KUNR with support from our 2023 National Fellowship.

A mileage sign along State Route 339 in Yerington, Nev., on Nov. 13, 2023.

Kat Fulwider/KUNR Public Radio

When Katarina Sepulveda was pregnant with her first son three years ago, she traveled more than an hour from Pahrump to Las Vegas for her prenatal visits with a midwife.

“I was also working in Las Vegas. My midwife was so flexible with me. We would schedule 7 a.m. appointments. I would have to leave my house at like 5 a.m., see her for my prenatal at 7 a.m., and then go to work after that,” Sepulveda said.

With her second baby, Sepulveda found a midwife and doula closer to home in Pahrump.

Katarina Sepulveda does a home birth with her midwife Faith Bosket (right) and doula Brandi Monje-Folkerts in Pahrump, Nev., on July 18, 2023.

Courtesy of Katarina Sepulveda

“It was a huge difference,” she said. “Especially now that I had my toddler and then I was expecting a new baby. Logistically that was going to be really hard, trying to find a sitter or bring him to appointments. It was much easier on our family to have somebody local.”

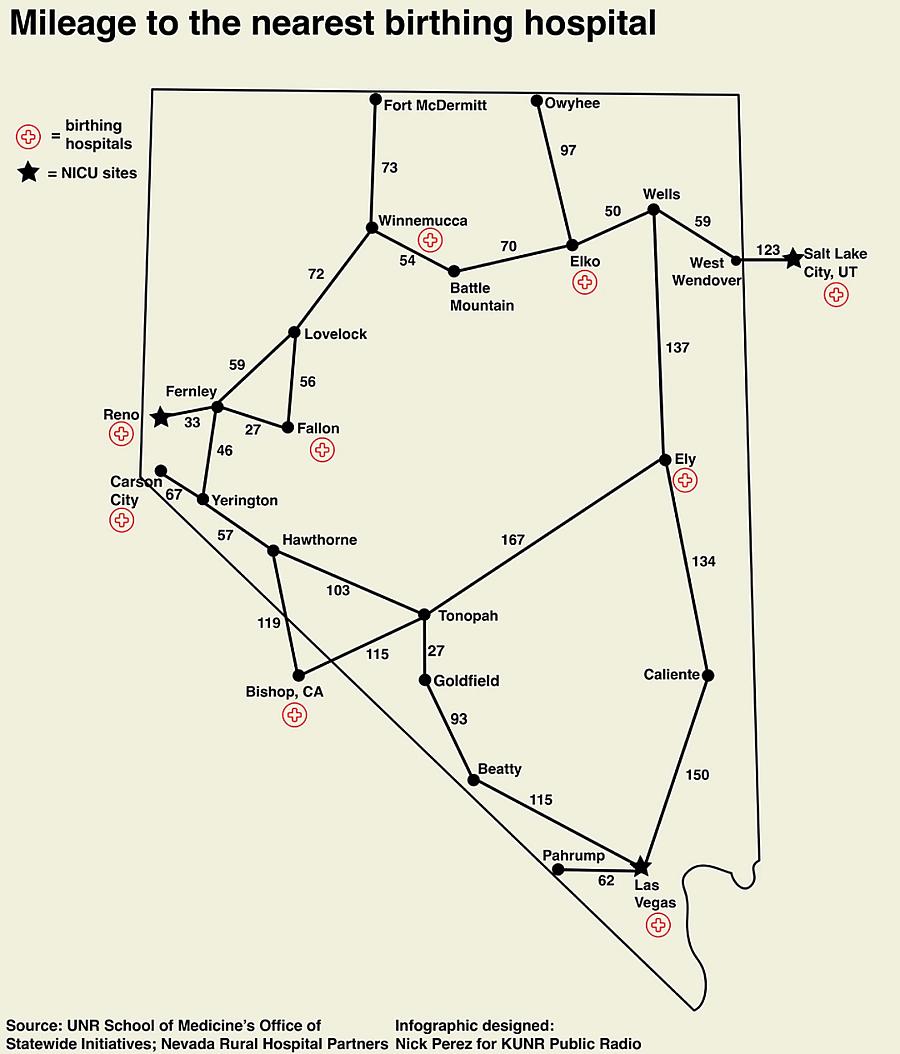

In Nye County, the largest geographic county in Nevada, there isn’t a hospital that offers obstetric care, and there aren’t any practicing OB-GYNs. When it came time to give birth, Sepulveda didn’t feel comfortable making the trip to Vegas, so she chose to do homebirths for both of her sons.

However, her insurance didn’t cover the cost of her midwife and doula. She paid out of pocket for care before, during, and after her pregnancy.

Instead of holding a baby shower, Sepulveda and her husband asked family members to donate to help them with the costs for their second baby. She wanted the additional support by her side because most of her family lives outside of the state.

Katarina Sepulveda and her husband, Kevin, and their newborn Alejandro after a home birth in Pahrump, Nev., on July 18, 2023.

Courtesy of Katarina Sepulveda

“Having a birth fund helped us pay for the birth team and the support that we really needed,” Sepulveda said. “That was definitely a game changer for us when we realized that it’s okay to ask for help.”

Sepulveda’s story is not unique. Areas with low and no access to maternal care affect nearly 7 million women and 500,000 births across the United States, according to a March of Dimes report released earlier this year. In Nevada, more than half of the counties are considered maternal health care deserts. That leaves expectant parents without a birth center, obstetric and gynecological providers, or a birthing hospital, said Ashley Stoneburner, manager of data science for the March of Dimes.

“That means that they don’t have access to a hospital that has specific obstetric services, so they have no OB beds where they can deliver babies,” Stoneburner said. “A lot of times, there’s a hospital, and the woman could deliver in an emergency room, but this means that there is no hospital with a birthing unit.”

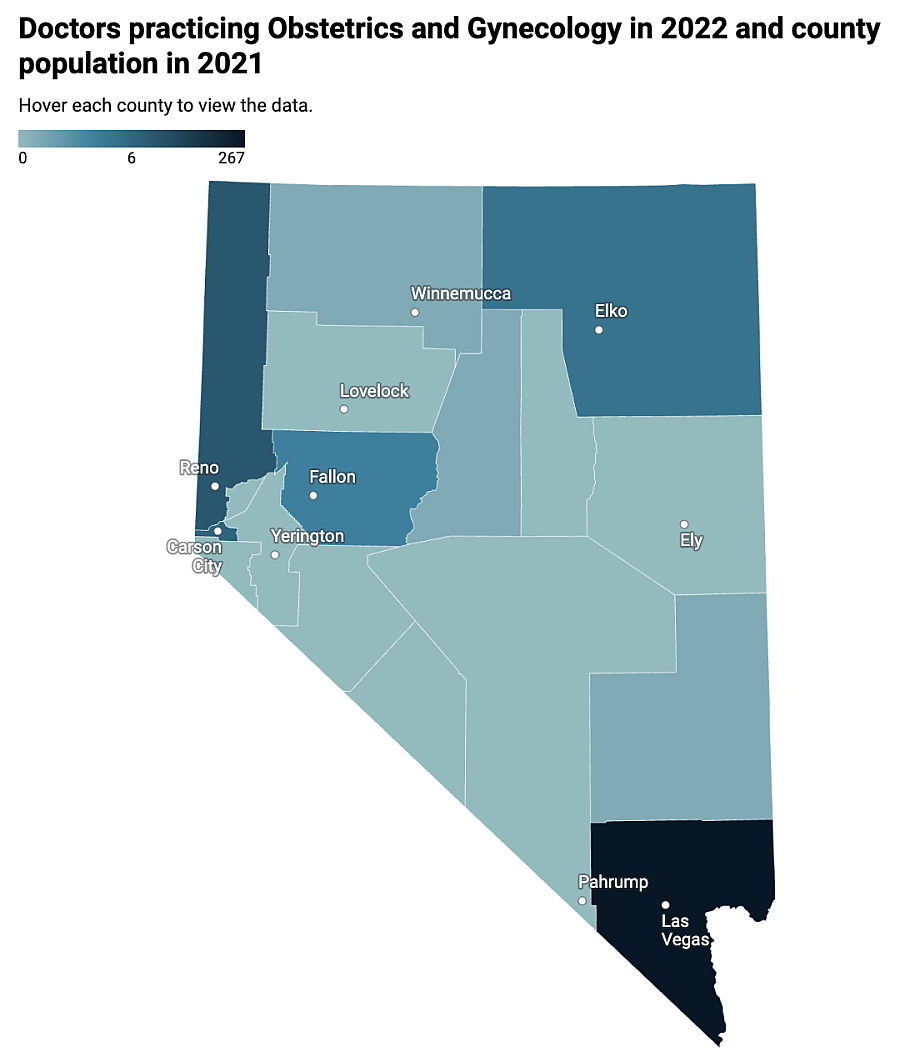

There's no data for Eureka or Storey counties. According to UNR School of Medicine’s Office of State Initiatives’ Dr. Tabor Griswold, the populations of Eureka, Storey and Esmeralda counties combined are less than 10,000 people which isn't enough to support a physician even if they were contiguous.

Across the U.S., two-thirds of maternal health care deserts are in rural counties. Parents and babies living in these areas have low access to preventative, prenatal, and postpartum care. They are also at higher risk of childbirth complications and maternal mortality.

Renown certified nurse midwife Lillian Bronson in Reno, Nev., on Oct. 18, 2023.

Kat Fulwider/KUNR Public Radio

Certified nurse midwife Lillian Bronson cares for rural patients at Renown’s women’s health clinic in Reno. She explained some of the barriers these patients face.

“People are oftentimes neglecting their health or not getting care when they should just because of lack of physical accessibility to providers, to hospitals, price of gas, child care, somebody to watch the kids while they come to an appointment,” Bronson said. “Pregnant patients will come not having gotten care, maybe ever or in a very long time.”

As a solution, Bronson would like to see more midwives being used. Midwives typically care for low-risk patients but can’t perform surgeries like OB-GYNs.

“A midwife is trained in a model of care that is very patient-centered,” she said. “We believe in viewing the patient as a whole person and all of the things that play into their health. So, culturally, their community, their values and beliefs, how that all relates to them, and how we treat them.”

Midwives help fill a void in these maternal care deserts. Only four out of 14 rural hospitals in Nevada offer routine labor and delivery, said Blayne Osborn, Nevada Rural Hospital Partners president.

“When you are looking at the map of the state of Nevada, we have roughly 95,000 square miles across the state, and if you draw a line horizontally across the state, those hospitals are located north of that line,” Osborn said. “When you start looking at some of these huge distances, miles and miles and miles of no labor and delivery services, that is truly what we’re talking about with an OB desert.”