Looming Long-term Snap Cuts Threaten SF Latinos Even as an Ecosystem of Restaurants and Food Banks Try to Fill Gaps

The story was co-published with El Tecolote as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

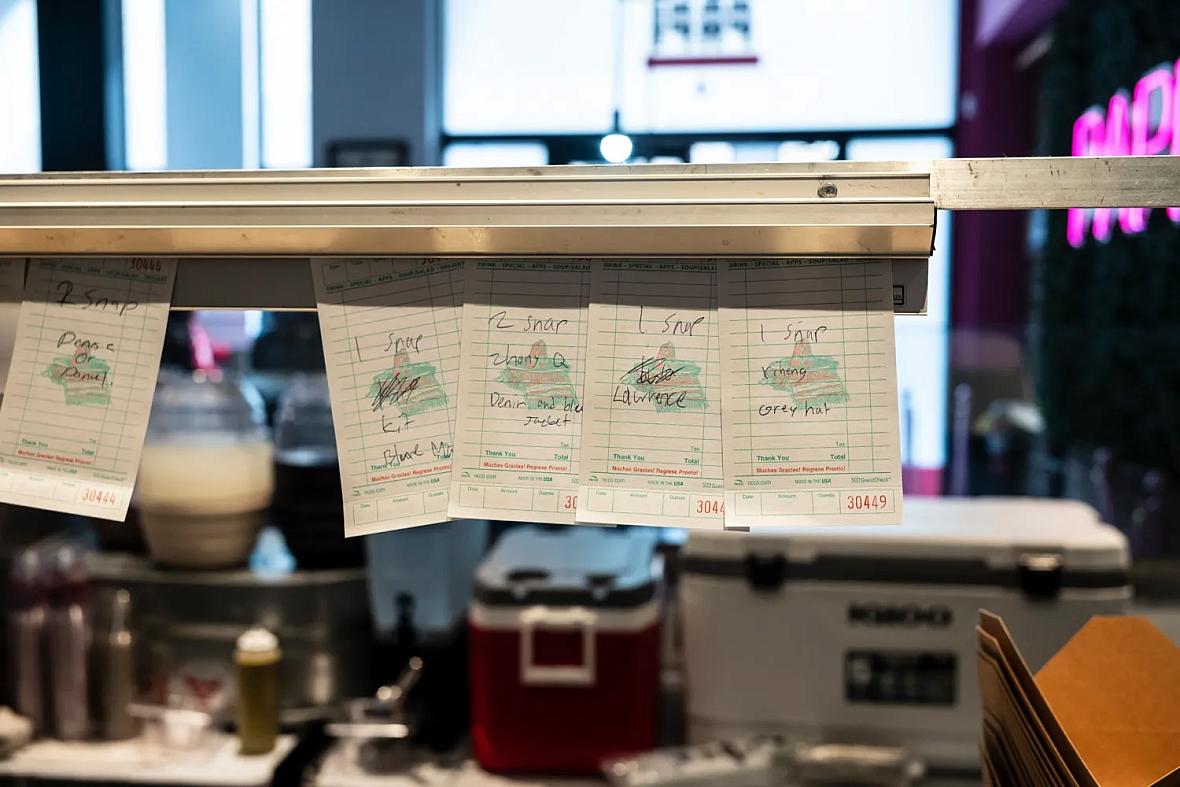

Orders for SNAP recipients wait on the counter at Al Pastor Papi in San Francisco, Calif., on Nov. 4, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

When the federal shutdown paused SNAP payments this November, Sandra M., 53, rushed downtown to San Francisco’s Al Pastor Papi to get free burritos for her family. Keeping her place in line was a struggle. The Mexican restaurant regularly sees a busy lunch rush, but its staff wasn’t prepared for the surge of people who showed up to the restaurant after hearing it would support those who had suddenly lost their SNAP payments .

It was hard not to feel the urgency in the crowd. People pushed through each other, trying to find a faster way to order — at one point, three separate lines formed for the same cashier. Demand was so high that management capped the number of free burritos at 100 per day.

9 free food pantries in San Francisco offering Latino staples

When she finally made it to the counter, Sandra showed her EBT card, driver’s license and asked for four burritos: one for herself, and one for each of her three sons. The cashier shook her head. The restaurant was only giving free burritos to people who showed up in person. Sandra decided it would go to her youngest son, who is 15 and “eats like two people.” Everyone else would have to miss the meal.

Melani Lara, 31, a manager at Al Pastor Papi, takes an order while SNAP recipients wait for their donated burritos beside the register in San Francisco, Calif., on Nov. 4, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

“I’m really worried. I don’t know how I’m going to feed them,” Sandra told El Tecolote. Living off her intermittent house-cleaning gigs, the family heavily relies on Sandra’s SNAP benefits to eat. But that week, her family had to turn to community handouts.

On Oct. 24, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced that, due to the federal government shutdown, it would pause SNAP benefits starting Nov. 1, leaving millions of people without cash assistance to buy food. To fill the gap, Bay Area communities scrambled to build their own safety nets. Dozens of restaurants like Al Pastor Papi began offering free meals to CalFresh (SNAP) recipients, food banks expanded deliveries and the city launched a philanthropy-backed partnership to distribute one-time prepaid grocery cards.

The disruption ended when the federal government reopened on Nov. 12, though a new pause may hit California again next week after the Trump administration threatened to withhold funds from states that refuse to share their recipients’ immigration-related data.

Marley Escabedo, 19, and Grendy Hernandez, 47, prepare orders for SNAP recipients at Al Pastor Papi in San Francisco, Calif., on Nov. 4, 2025.

Orders for SNAP recipients ready for pickup at Al Pastor Papi on the same day. Photos: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Local organizations have stepped in to support people through these scrambles, which have exposed just how fragile access to food has become for families like Sandra’s. But advocates warn that these pauses and political standoffs are only a preview of looming, long-term federal cuts that could push more than half a million Californians into food insecurity, with no quick rebound in sight.

“These projected losses equal about 1.1 billion meals lost annually in California,” said Noriko Lim-Tepper, Chief of Strategic Partnerships at the San Francisco-Marin Food Bank. Last year, all of California’s food banks combined distributed about 650 million meals.

“We can’t food bank our way out of this problem,” she said.

Permanent federal cuts might soon bring a deeper crisis

Josiah Miller, 22, a SNAP recipient, holds his EBT card inside Al Pastor Papi in San Francisco, Calif., on Nov. 4, 2025. “I need it and my friends need it, and we’re struggling, but we’re all here just trying to get fed,” said Miller. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Josiah Miller, 22, a SNAP recipient, holds his EBT card inside Al Pastor Papi in San Francisco, Calif., on Nov. 4, 2025. “I need it and my friends need it, and we’re struggling, but we’re all here just trying to get fed,” said Miller. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

In July, Congress passed a new budget reconciliation bill that is set to eliminate around 20% of SNAP’s funding over the next decade. The decision, which has been controversial along political party lines, is expected to drastically reduce access to stable food sources for hundreds of thousands of people across the country.

According to the California Budget and Policy Center (CBPC), the cuts will cost California more than $2.5 billion in CalFresh funding each year. More than 754,000 Californians could lose benefits entirely, while over three million households could face reductions, affecting the vast majority of people on CalFresh.

Local agencies are bracing for the fallout. During the November pause, the San Francisco-Marin Food Bank saw a 205% increase in traffic to its food locator website, a preview, Lim-Tepper said, of the pressure local resources will be under with less federal support as more budget cuts are implemented over the course of the next two years.

Volunteers grab gloves inside the San Francisco–Marin Food Bank warehouse on Nov. 20, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

“The government shutdown was a clear example that hunger is a policy issue,” she told El Tecolote, adding that 125,000 people in San Francisco and Marin County rely on SNAP. “[It’s] really a preview of what’s to happen if all of the provisions are implemented, all of the cuts to SNAP are implemented.” The food bank projects that at least 7,500 of them could lose their benefits next year as a result of these cuts.

Meanwhile, Tangerine Brigham, Deputy Director and Chief Operating and Strategy Officer for the San Francisco Health Network, estimates that around 20% of San Francisco’s CalFresh population will be at risk of losing benefits due to new work requirements and administrative changes. Managing the increased demand and local cost sharing alone is expected to cost the city $62 million.

Though the city is prepared to work to mitigate the impact, “difficult financial decisions” are ahead, Brigham said in a Nov. 17 Health Commission meeting.

The impact of food insecurity on health and immigrants

Health experts say the coming cuts will have profound consequences on SNAP recipient’s’ wellbeing. The American College of Physicians (ACP) notes that food insecurity is associated with a wide range of health issues, including cognitive problems, asthma, diabetes and other chronic diseases.

Without food aid, research has found that families often skip meals, ration food, or rely on low-quality, low-nutrition options, all of which worsen long-term health outcomes, including a higher risk of developing diabetes. One study found that food insecurity is linked to a higher risk of premature mortality and shorter life expectancy.

In San Francisco, Latino families have been disproportionately burdened by rising costs since the start of the pandemic, prompting community organizing around housing and food access. But these new federal cuts pose additional challenges.

Some of the new SNAP budget cuts specifically target certain immigrant communities. The federal bill eliminates food assistance for many people with temporary legal status who previously qualified, including asylees and certain survivors of domestic violence who self-petition under the Violence Against Women Act.

Under the new rules, immigrants with particular temporary statuses can no longer enroll in SNAP. Those who already received benefits are set to lose them at recertification, according to recently implemented USDA guidance. On Oct. 31, the USDA issued additional guidance saying that green-card holders who were previously asylees and refugees would no longer qualify for SNAP benefits either, though that guidance is currently being contested by 21 states in a federal lawsuit.

Volunteers prepare to distribute food inside the Mission Food Hub, a volunteer-run food cooperative in San Francisco, Calif., on Nov. 7, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Also being legally contested is the Trump administration’s efforts to obtain SNAP recipients’ personal data, including names and immigration statuses. In October, a federal judge blocked the federal government from withholding SNAP funding from states that refused to share this information, including California. But the Trump administration has indicated it may still attempt to withhold these benefits from all recipients in those states as early as next week

For many noncitizens, the changing policies add on to an already destabilizing year.

“I’m really worried, also because with everything going on with immigration they can send me back to my country,” said Sandra, who immigrated from Honduras and has lived in San Francisco for 29 years.

Sandra had previously qualified for SNAP because she had Temporary Protected Status (TPS), which the Trump administration successfully terminated for all Hondurans on Sept. 8. Under current federal guidelines, she will not be able to renew her benefits when she is next slated to re-apply.

Bay Area reality: Rising costs and community response

At the Mission Food Hub on the first Friday of November, volunteers spent the morning opening boxes of vegetables and separating groceries for the hundreds of people expected that afternoon. The pantry serves many low-income residents, including those who are either ineligible for SNAP or are wary about applying.

Founder Roberto Hernandez said the shutdown pause triggered a surge in calls: 20 to 40 a day during the first week of November. But in the months prior, Hernández said more families were also seeking support from pantries as the cost of living in the city continues to rise.

Roberto Hernandez, founder of the Mission Food Hub, stands inside the volunteer-run pantry in San Francisco, Calif., on Nov. 7, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

“Ten years ago with $100, you would go into Safeway [and] come out with four bags,” said Hernandez. “Today, with a hundred dollars you come out with one bag.”

A recent analysis by the nonprofit Tipping Point Community found that nearly three in ten Bay Area residents struggled to make ends meet in 2023, even when half of those living in poverty work full time. Others earn just above eligibility thresholds for safety net programs, leaving them without government support despite being unable to cover high living costs.

This is the case for Susana Milian, 55, who lives in an apartment with her daughter and 8-year-old grandson in the Mission District. Her daughter’s salary as a social worker barely covers their nearly $2,300 rent and utility bills, and the family is only able to cover their groceries because Susana qualifies for SNAP.

Fresh produce arranged for distribution. Photos: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Diagnosed with arthritis, Milian uses a cane to walk and says she cannot work. Instead, the Guatemalan grandma cares for her grandson, who has autism. It’s hard for her to make the $300 a month she gets for groceries to cover the food needs of three people, but they try to make the most of it by going to budget and warehouse retail stores, like Costco and Grocery Outlet.

But even this support is fragile. During the November shutdown, they “were either paying for rent or food,” Milian told El Tecolote.

Milian has lived in San Francisco for most of her life, but after the pandemic, she says the city has started to feel impossible to afford.

“I’ve talked with my family about moving to Fresno, which is cheaper,” she said. “But honestly, I can’t get used to that. My daughter can’t get used to it either. And the support we get, the education, [it’s] different here.”

A community response stretched to its limits

As the holidays approach, many groups have extended their emergency programs until the year ends, even when SNAP has been fully restored, for now.

Al Pastor Papi, for instance, ended its free burrito program after the first week of November but now offers free tacos on Saturdays to children on SNAP and discounts for parents who present their EBT cards.

Grendy Hernandez, 47, a cook at Al Pastor Papi, looks over orders for SNAP recipients in San Francisco, Calif., on Nov. 4, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

“It’s impactful for us too,” said manager Melanie Lara. “Some of us have gone through similar situations. And it’s been very special and important to help people who might not have something to eat otherwise.”

The San Francisco-Marin Food Bank is similarly keeping its Community Response Program until the end of December, including expanded home-delivered groceries for families who feel unsafe or are unable to travel to pantries. With deeper federal cuts looming, Lim-Tepper said her team is pressing for more donations, volunteers as well as local and state-level solutions that can soften the blow next year.

“SNAP and CalFresh are not only anti-hunger tools, but also economic drivers. So they put dollars in the economy,” she said. “Food is food is a human right.”

Despite the challenges ahead, both Lim-Tepper and Lara emphasized that community organizations will continue showing up for the families who need them.

“I just want to let people know that they’re not alone,” Lara said. “We’re paying a lot of attention to the Latino community, especially because of everything that has been going on, and we will always be supporting them.”

Inside the Marin Food Bank warehouse, which 60% of their produce are fresh vegetables and fruits serving about 250 neighborhood pantries in San Francisco, Calif., on Nov. 20, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California”, a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.