The Loss of Chinatown’s Local Businesses Is Creating a Health Desert

The story was co-published with World Journal as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

A closed storefront in Chinatown. (Jian Zhao/World Journal)

In Los Angeles’s Chinatown, the signs of decline are impossible to miss — shuttered restaurants, boarded storefronts, and fewer pedestrians on once-crowded streets. Beneath the economic downturn, there also lies a quieter public health crisis.

A desolate street in Chinatown

For decades, this dense neighborhood — less than a third of a square mile but home to nearly 37,000 people — has served as an informal ecosystem of care. Elders who didn’t drive could walk to buy groceries, refill prescriptions or herbal tonics, chat with longtime shop owners, or sit down with friends to enjoy the familiar flavors of home. These small acts of mobility, trust, and cultural connection once sustained both their health and the broader community life.

Now, the store closures, and displacement reshaping Chinatown are quietly eroding not just businesses but also the community’s emotional and physical wellbeing.

Food is harder to get

“Now I don’t even know where to buy jiàng yóu (Chinese soy sauce),” said 85-year-old Chinatown resident Huirong Wu. He used to do all his shopping within a few blocks — groceries, vegetables, daily necessities — everything was close by.

These days, he makes one grocery trip a week, pushing a grocery shopping cart and taking the No. 90 or 94 bus to a Super King Market several miles away, where he can still find a few vegetables familiar to Chinese cooking, like bok choy and a special variety of cabbage favored in Chinese households. The round trip alone takes nearly two hours.

“Buying rice is the hardest,” he said with a sigh. “It’s too heavy, so I have to ask my children to bring it.” Wu’s two children live in Riverside and Irvine, each driving dozens of miles to deliver bags of rice when his supply runs low.

Over the past few years, major chain stores have closed one after another. The last two full-service Chinese supermarkets — G&G Market and Ai Hoa Supermarket — shut down in 2019 after serving the community for decades. More than 3,000 residents and their families signed petitions urging city officials to intervene, but the stores never reopened. Since then, only a scattering of street vendors and small, struggling grocers remain, cutting off affordable food access for residents who once depended on stores within walking distance.

“Small shops or street vendors can’t compare,” Wu said. “Since Ai Hoa closed, we can’t find bitter melon, Chinese broccoli, or the key seasonings for Chinese cooking like jiàng yóu, black vinegar and cooking wine we used to buy.”

He noted that some seniors now travel to Monterey Park — a predominantly Chinese community almost an hour away by bus — to shop at Chinese supermarkets that still offer the ingredients and flavors they’re used to.

Even the few local stores that had managed to hold on are now disappearing. After 18 years in business, Yue Wa Market, a small fresh-produce and dry-goods shop located downstairs from Wu’s apartment, closed this month.

“Before, everything was just downstairs,” recalled 76-year-old resident William Huang, who has lived in Chinatown for more than a decade. “Now there isn’t a single decent supermarket left. ”

Huang considers himself lucky because he can still drive — something uncommon among Chinatown’s elderly residents. “Most elders in Chinatown don’t have cars,” he said. “They have to take the bus or even wait for their children to get off work to drive them back home. And their children may live in other cities.”

According to a UCLA report, nearly one-quarter of Chinatown’s population is elderly — aged 65 or older (24%). The proportion of seniors in Chinatown is significantly higher than that of Los Angeles County overall (11%). More than 40% of families in Chinatown live below the poverty level, compared to 13% countywide.

Affordable housing in Chinatown. (Jian Zhao/World Journal)

A new pharmacy desert

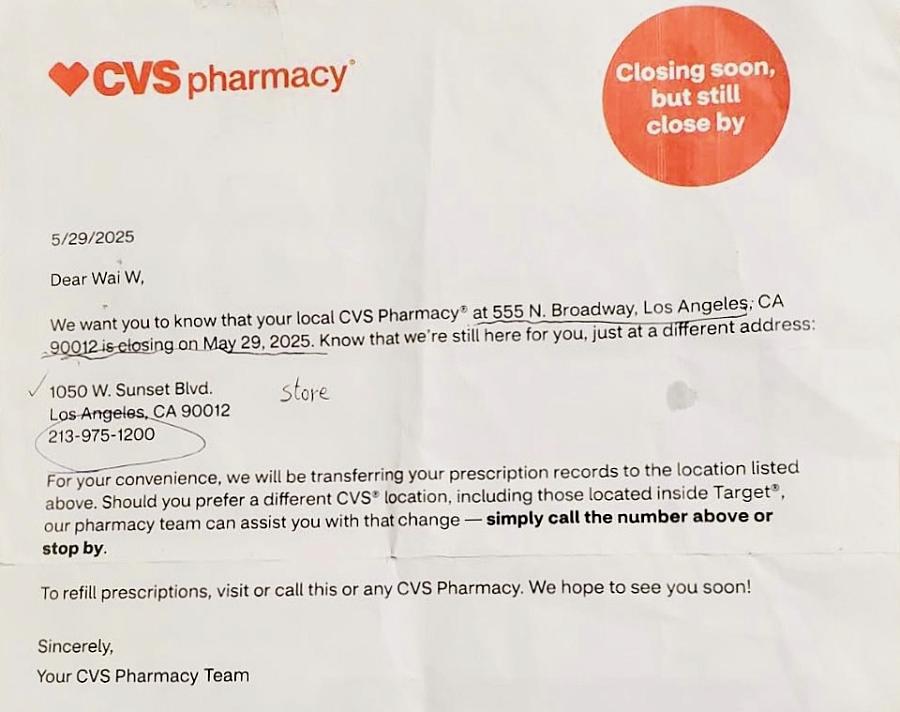

Pharmacies are disappearing as well. The only chain pharmacy CVS in Chinatown has remained closed since May 29 this year.

CVS closure notice. Courtesy Huirong Wu)

Wu still keeps the closure notice because he needs to pick up his medicine. As a pancreatic cancer survivor who needs short- and long-acting insulin injections 4 times a day, access to medication is crucial.

After the closure, he now has to take a bus three stops to another CVS on Sunset Boulevard to refill his prescriptions every month or two.

In Chinatown, only a few small pharmacies remain. “The local pharmacies can’t help,” he said. “They don’t sell insulin — they say it’s not profitable.”

For elderly patients like Wu, traveling outside Chinatown for care is a struggle when language barriers stand in the way.

“I don’t speak English, so it’s really hard. I don’t know how to buy medicine,” he said. Finally, Wu has learned to use his phone to translate, pointing at the screen to show pharmacy staff what he needed. But every trip remains a challenge. “When I get older. I’m not sure I’ll be able to manage.”

The few remaining Chinese traditional herbal shops are also barely surviving.

Prices for herbs and remedies have surged 35% to 45% since the pandemic, driven by tariffs, shipping delays, and supply shortages, said Emily Jiang, owner of Far East Center, a decades-old, family-run traditional Chinese herbal pharmacy. “Herbal ingredients have gotten so expensive. We’re surviving by using the stock we saved from before.”

Residents like Wu worry these stores will soon disappear. Every weekend, he brews herbal tea with ingredients like prunella, dandelion, luo han guo, and Chinese yam —traditional Chinese remedies believed to support his body. It’s a common habit among Cantonese elders.

“If these herbal stores all close too,I really won’t know where to go for them,” Wu said.

Public health experts warn about “pharmacy deserts” in low-income urban minority communities, where chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and respiratory illness are common. The loss of nearby pharmacies can deepen health inequities by making it harder for residents to access medication, vaccinations, and preventive care — imposing significant clinical and economic burdens on the health care system, according to research.

Doing Business Under Pressure

Business owners say the cost of staying open has soared — driven by import tariffs, rising rents, higher labor expenses, and a sharp drop in foot traffic. But worsening public safety, they add, has become one of the most serious challenges.

“Public safety has become a major concern for businesses across Chinatown,” said Chester Chong, president of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce of Los Angeles, a nonprofit founded in 1955 that supports local businesses and promotes economic development in Chinatown.

According to Chong, business owners report frequent thefts, robberies, and disruptions, all of which have scared away both merchants and customers. Foot traffic has dropped sharply in recent years.

“These days, the streets empty out by late afternoon,” Chong said. “Most stores close early.”

Security guards stand in front of jewelry shops. (Jian Zhao/World Journal)

October 5, one more business was burglarized. A convenience store on North Broadway selling beverages and snacks was ransacked by a group of motorcyclists. The owner, Ms. Zhou was injured while trying to stop them.

Yue Wa Market owner Amy Tran, said her house was burglarized three times. Far East Center owner Emily Jiang, said her family’s car tires were slashed twice, and their home was broken into during repairs.

Arson has also become a recurring threat. In February, two long-standing Chinese businesses — Hong Ning Co. Inc., a traditional herbal store, and Broadway Cuisine, a restaurant — were set on fire. The former shut down permanently, while the latter only recently reopened.

The fire-damaged store, Hong Ning Co. Inc., is now up for sale. (Jian Zhao/World Journal)

Beyond safety, businesses face a web of structural pressures: limited parking, high labor costs, and the growing burden of rent due to gentrification. Chong also noted that tariff increases have also driven up supply costs, and some imported goods have become nearly impossible to find.

Meanwhile, ICE raids earlier this year triggered widespread fear among workers — even those with legal status.

Over 20 years East Garden Restaurant owner Huang shares, ICE arrests left many workers afraid to show up, even those with legal status.

He also added protests and curfews in downtown Los Angeles in June forced him to close for two weeks. The growing homeless people coming to his restaurant, rising rent, and unstable labor costs make it even harder to keep the doors open. “I’ll keep going as long as I can,” he said.

Adapting to survive

Amid the challenges,,business owners have learned to adapt to stay afloat.

Emily Jiang’s family has operated Far East Center for more than 40 years. The wooden apothecary cabinet filled with herbs and tonics — once the focal point of the store — now stands at the back.

“People still come for herbs,” she said, “but not like before.”

To keep the business alive, Emily began selling other products. “We started adding small items just to get by,” she recalled. Today, the store looks more like a compact Asian grocery market, stocked with coffee, teas, snacks, and daily supplies.

The family-run herbal pharmacy has transformed into a compact Asian grocery store. (Jian Zhao/World Journal)

She has even developed her own herbal teas that she claims help with digestion and weight management, hoping online sales can sustain the store. Her son, a realtor by trade, helps part-time, learning how to the traditional Chinese medicine formulas and daily operations.

After thieves stole valuable herbs and smashed her cash register, Emily installed new iron gates inside the store, added security cameras, and began closing earlier than before to deter potential robbers. “We have to protect ourselves,” she said.

Still, Emily is uncertain about the future. “I don’t know what will happen,” she said, glancing at the aging wooden cabinets. “These were made by old immigrants. Now no one knows how.”

Emily introduces the 40-year-old apothecary cabinet.(Jian Zhao/World Journal)

Emily introduces the 40-year-old apothecary cabinet.(Jian Zhao/World Journal)

Resilience and Loss

Beneath the exhaustion, small acts of resilience have begun to rise. Some elders have turned into street vendors, pushing carts and spreading plastic sheets on the sidewalk to sell homegrown vegetables, fruits from nearby markets, or surplus household goods. These informal stalls, often unpermitted but tolerated by the community, offer affordable produce and familiar flavors to neighbors who no longer have nearby access to shop.

Elderly residents sell homegrown vegetables, fruits, and surplus household goods. (Jian Zhao/World Journal)

(Jian Zhao/World Journal)

But the broader ecosystem continues to thin. Each year, another herbal shop, restaurant, or grocery disappears—taking with it not only affordable food and cultural habits, but also access to fresh produce and medications that support residents' health, along with the daily social connection that once tied the community.

"Now there's nowhere to go in Chinatown," Wu sighed. "Life feels boring — fewer people, fewer stores."

For Wu, the outside world has shrunk to the glow of a screen — watching the news and online videos all day.

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California”, a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.