The Misidentified

Día de los Muertos altar honors COVID dead at Sherlock Elementary School, 2021.

Photo by Michael Izquierdo for palabra

Editor’s note: Click here to read the version in Spanish.

It started with a casual perusal of COVID death statistics in the summer of 2020. Journalist Ana Arana found that Latinos across the country were routinely misidentified ethnically and racially. The anomalies were easily missed by most media. But Arana’s instincts told her that at stake were significant public health consequences for Latinos. What ensued was a year-and-a-half-long palabra investigation into widespread misclassification of Latino COVID deaths that health officials acknowledge but have done little to correct. This story is a wake-up call.

—Linda Jue, project editor

This story was produced in collaboration with Cicero Independiente.

Elizabeth Solano, a resident of Cicero, Illinois, was pregnant with her first child when she went to the hospital in March 2020 for a routine ultrasound. There, she was diagnosed with complications from the newly emergent coronavirus and underwent an immediate C-section. Several days later, she was declared well enough to go home with her baby.

However, Solano was soon readmitted and then died of COVID complications.

Her death led local newscasts. She was among the first casualties of the pandemic in this small Chicago suburb where 90% of residents are Latino. Her close-knit family was stunned by the seriousness of COVID-19. So much so that Elizabeth’s brother told a reporter on a Chicago news show that he wanted people to know how deadly the virus was. (The Solano family did not respond to multiple interview requests from palabra.)

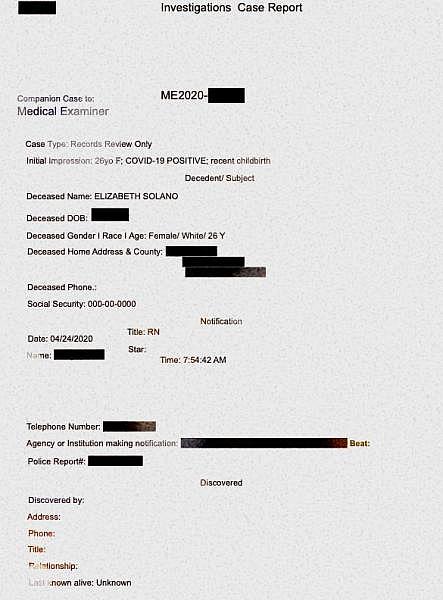

Solano’s death would prove to be another significant first, one that would not be discovered until a year later. A review of her death certificate by palabra revealed a serious error that has been repeated on death certificates of Latinos around the country since the beginning of the pandemic: Elizabeth was misidentified as white in hospital records.

Elizabeth Solano. Courtesy Bormann Funeral Home

When a person dies, the death is supposed to be properly accounted for in hospital and medical examiner records regardless of where it occurred. Around the nation, even the most sparsely populated records tend to include a patient’s name, address, next of kin, and important demographic data such as race and ethnicity. This information has been even more critical during the COVID pandemic, in which serious gaps in healthcare for communities of color have come to light and been alarmingly exacerbated.

We already know that Latinos have been disproportionately impacted by COVID, dying at nearly twice the rate of white Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But the extent and impact of these disparities among Latinos are significantly underestimated when Latino COVID deaths aren’t counted properly.

“There are healthcare resources that are targeted at communities, whether that’s vaccinations or treatment options,” said Thomas Saenz, president and general counsel of the Los Angeles-based Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF). “And if you are using inaccurate data, you are going to target those resources improperly. The public health implications are severe, and not just for the Latino community because we all interact.”

Since the start of the pandemic, palabra researchers have tracked Latino death data in various U.S. cities. In a review of 2020 medical examiner data for a number of counties nationwide, the researchers noticed that Latino surnames were being identified as white, Black, or other, although the records allowed for more precise classification of ethnicity such as Latino or Hispanic.

Elizabeth Solano's redacted 2020 death certificate from the Cook County Medical Examiner.

To dig deeper into this issue, palabra selected Illinois’ Cook County – which includes the city of Chicago – out of dozens of possibilities around the country because its large Latino population lives in historically segregated areas. This segregation, ironically, made it easier to double-check public data. In addition, the Cook County medical examiner provides detailed, up-to-date death records, unlike many other counties across the U.S. during the pandemic. The city of Cicero was then selected as a microcosm of the impact of death certificate miscounting nationally because the town has only one ZIP code and is overwhelmingly Latino.

COOK COUNTY

Between March 2020 and December 2021, the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office handled 27,551 deaths, nearly twice the number before the pandemic. COVID accounted for nearly half, or 12,913 of those deaths.

Looking at the numbers for a year that is considered the deadliest to date, the county’s medical examiner reported total COVID deaths for 2020 were 8,353. Of those, 1,810 were identified as Latinos, or almost 22%. In 2021, there were 4,560 COVID deaths in Cook County. Some 19%, or 862 people, were identified as Latinos.

But palabra also found that the number of Latino deaths is actually higher than the medical examiner determined. A review of Cook County death statistics found an additional 372 misclassified Latino deaths in 2020 and another 108 in 2021. These figures raise the yearly percentages of deaths to 26% in 2020 and 21% in 2021. Adding both years, Latinos averaged 24%, or nearly a quarter of all COVID deaths.

Given that Latinos are the second-largest population group in Cook County – nearly 820,000 residents compared to 864,000 white non-Latinos, according to the 2020 U.S. census – correctly documenting Latino mortality is vital to assessing proper access to COVID treatment as well as to other pandemic-related resources.

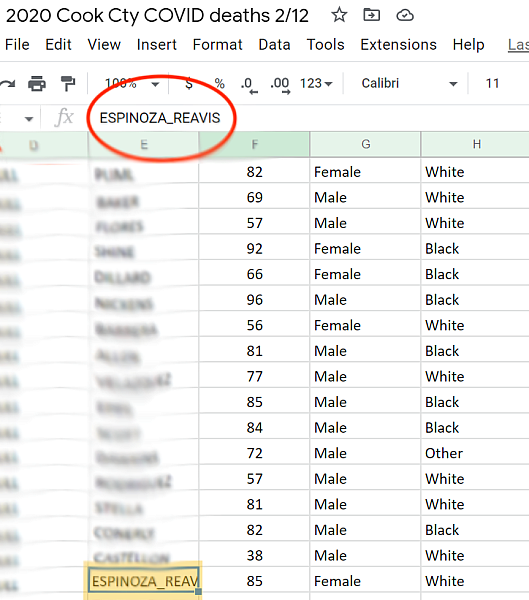

In one record, the name “Reavis” appears. It was actually a Rivas who had died.

To find Latino misclassifications in medical examiner records, palabra examined Cook County death statistics and sorted out Latino surnames from the people who were identified as white, Black, or other in racial classification. We then took these names and searched for their obituaries online. We also looked at the ZIP code where each person lived to check if it was a known Latino-majority community. Even still, there is an inevitable margin of error in our methodology. We were only able to focus on Latinos with Spanish surnames because we could not identify the percentage of Latinos with other surnames. We were also aware that our count of Latino surnames included people of mixed races such as Black, Asian, and white Latinos.

Our review of death records unveiled other problems in the official accounting of deaths.

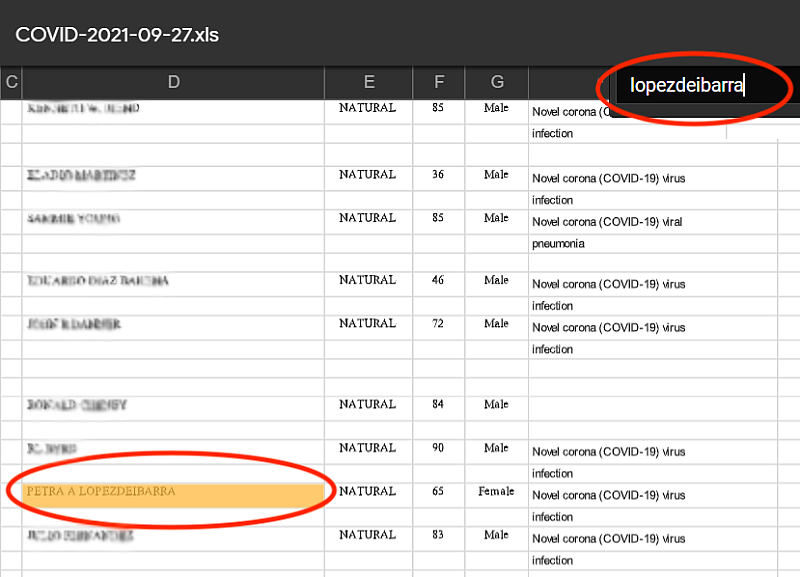

Some intake forms misspelled common Latino names. In one record, the name “Reavis” appears. It was actually a Rivas who had died, as palabra researchers confirmed in an online obituary for the same person. Similarly, compounded Latino names were sometimes jumbled. In one case the name López de Ibarra was listed as “Lopezdeibarra.”

The table above, created by palabra researchers, identifies Latinos labeled as white in the Cook County Medical Examiner data and whose compound surnames were collapsed into one. Another example of a Latino name misspelled in the Medical Examiner's data. Source: Cook County Medical Examiner

Cynthia Duarte. Courtesy Duarte.

According to Cynthia Duarte, director of the Sarah W. Heath Center for Equality and Justice at California Lutheran University, the problem of correctly recognizing race and ethnicity in medical settings stems from procedures not designed to serve diverse populations, especially during emergencies. Too often, patients are checked-in by intake workers with no training in cultural literacy. As a result, they tend to go only by skin color and other visible “racial” traits, which are highly subjective assessments – particularly when dealing with mixed-race populations such as Latinos and Native Americans.

“This has happened to me in a hospital,” said Duarte. “I am Latina and dark-skinned, so a lot of assumptions are made about who I am.”

CICERO AND DAY OF THE DEAD

Most of the 90,000 residents of Cicero live in multi-generational households, and a good number are undocumented. Many extended families – aunts, uncles, and in-laws – also live within a few blocks of each other.

In this cramped, urban community, the pandemic’s rapid onset in March 2020 rang alarm bells. Within seven months, the town reported 5,635 cases. A total of 212 died from COVID between 2020 and 2021, including Elizabeth Solano.

Day of the Dead observance includes dozens of Cicero's citizens lost to COVID. Sherlock Elementary School. Photo by Michael Izquierdo for palabra

Reflecting its population, the majority of Cicero deaths were Latinos. And, just as in Solano’s case, at least 10% of those were misidentified as white, Black, Asian or other.

The first sign of this problem appeared in 2020 to Irene Romulo, development and community engagement coordinator at Cicero Independiente. To update the news site’s weekly count of COVID deaths, she followed reports from the local medical examiner's office. While reviewing the names of the victims, Romulo noticed that family members and neighbors who died of COVID were identified as white - with no ethnicity listed - in official records.

“I was devastated to find out that in death my grandfather was identified as a race that didn’t match who he was,” she said.

The dramatic impact of COVID on the residents of Cicero was evident during a visit to Sherlock Elementary School in early November 2021. Students, parents, and school staff had erected a Día de Los Muertos altar for the annual ceremony honoring passed loved ones that’s a tradition for many Latinos. The altar had several tiers displaying dozens of photos. School officials said they were overwhelmed with participants, especially as the school community had not observed the holiday in previous years.

COVID MISREPORTING FROM THE START

From the onset of the pandemic, Chicago officials and community leaders debated whether and how to gather COVID data on Latinos. In April 2020, Latino-elected officials, aware that their constituents were being overlooked in public health assessments, asked government agencies to improve data gathering in Latino communities. At the time, 70% of recorded deaths were Black Chicagoans, according to an early analysis of Cook County Medical Examiner’s data from WBEZ. City officials focused outreach efforts on those residents. Because of the lack of accurate data, the impact on Latinos was not adequately assessed.

“They were just not asking the right questions of Latinos,” said Illinois state Senator Celina Villanueva, who represents part of Cicero.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) researchers have long been aware that the number of Latino deaths from all diseases is continually underreported.

Once agencies tightened up their data-gathering methodology, officials began to see the real pandemic numbers among Latinos. Low-income municipalities began receiving CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security) Act grants to help offset the disease’s impact. Cicero received over $1 million in 2020. Cook County assigned the funds following a Social Vulnerability Index, which measures poverty levels, ethnic makeup, minority status, housing, and access to healthcare. The funds were to be invested in COVID preparedness for 2021. However, an investigation by the bilingual newsweekly Cicero Independiente found that the local government used the funds to pay police salaries, provoking public outrage.

THE UNDERCOUNTING CONTINUES

Elizabeth Arias. Photo Courtesy Arias

CDC researchers have known for 20 years that up to 3% of all Latino deaths in the United States are misclassified as non-Latino whites and not counted accurately in total death data. “They are counted, but as part of the general white population,” said Elizabeth Arias, a CDC researcher who has analyzed national death data since 1980. The misidentification of Latinos who died from COVID is not limited to Cook County. Nor is the misidentification limited to COVID deaths. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) researchers have long been aware that, nationally, the number of Latino deaths from all diseases is chronically underreported. The coronavirus forced this reality to the surface.

Moreover, COVID and its variants complicated reporting for Latinos in ways that didn’t affect the other ethnic and racial groups. Until 2019, Latinos fared relatively well in national health trends because they had maintained a higher life expectancy compared to non-Latino whites. In what researchers call the Hispanic Mortality Paradox, Latinos lived, statistically, two to three years longer.

The reasons for the “paradox” lie in a number of assumptions not yet definitively proven. The most accepted explanation, according to Arias, is that Latinos fared better because overall they include a healthier population that does not smoke.

However, this so-called advantage seems to have disappeared with the outbreak of COVID.

“It is true that deaths are difficult to hide. And that they do tend to be recorded well, but we still fall short when it comes to certain features like race, ethnicity, on death certificates.”

Disparities in healthcare, employment, and housing had their impact during the pandemic. Latinos lost three years of life expectancy between 2019 and 2020, according to Arias, while white non-Latinos lost less than two. The largest decline in life expectancy was among Latino males, down from 79 years in 2019 to 75.3 years in 2020.

“The pandemic highlighted known issues with the reporting of race and ethnicity in mortality statistics, which we are working on addressing,” said CDC epidemiologist Margaret Warner. “What is now more appreciated is the real-world impact of the statistics.”

Misclassification is a “pervasive problem” throughout all of the government’s data collection efforts, said Dr. Eric Schneider, executive vice president of the NCQA Quality Measurement and Research Group, which focuses on healthcare issues.

A health services specialist, Schneider said health experts know that mortality statistics are not completely reliable. “It is true that deaths are difficult to hide. And that they do tend to be recorded well, but we still fall short when it comes to certain features like race, ethnicity, on death certificates.”

FUNERAL DIRECTORS AND DEATH CERTIFICATES

CDC’s Warner and Arias said it is difficult to correct the misclassification of Latinos because the information comes from death certificates, which are completed by funeral directors and attending physicians, or other medical personnel.

It wasn’t until 1989 that the term “Hispanic origin” was added to the official U.S. death certificate.

The CDC developed training materials to guide funeral directors and medical personnel who fill out the forms, Arias added. These resources are supposed to teach funeral directors how to inquire about the race and ethnic origin of the deceased. But too often, these protocols are ignored.

“They are supposed to ask what did the dead person consider themselves,” said Arias. “Were they Hispanic, and what race were they? But many times the funeral directors go by observation only.”

Problems with gathering the correct information arise when the states collect the mortality data and the death certificate is filled out, Arias told palabra. The federal government pays states to provide the information, and the states depend on the information filled out by funeral directors, who are often not properly trained.

AN ENDEMIC PROBLEM

It wasn’t until 1989 that the term “Hispanic origin” was added to the official U.S. death certificate. Until then, only a handful of states included the Hispanic/Latino tag on their government documentation. The federal government did not include the term and provided “race” as the only identifier.

“Perhaps we all should carry identification that spells out our race and ethnicity to avoid misclassification,” Arias said wryly.

Some government agencies and Latino organizations have tried for some time to get to the bottom of misclassification. But solving the problem isn’t a simple matter of better training of government and healthcare personnel, or of funeral directors, said Cal Lutheran sociologist Duarte. Misclassification also occurs because of how Latinos identify themselves. Many foreign-born Latinos do not identify by the catch-all terms Latino or Hispanic. Instead, they often prefer to say they are Mexican, Salvadoran, or other nationalities.

“If data is wrong in terms of (COVID), where does this lead us in terms of other diseases?”

In Cook County, Latino elected officials ponder solutions. The Latino undercount in Cook County death records can’t be solved by the government alone, said state Senator Villanueva. The problem requires multiple stakeholders to figure out a solution

Cook County, Villanueva argued, needs to gather the medical establishment, data personnel, and the communities for a long-overdue discussion on proper data gathering.

Illinois state Senator Celina Villanueva. Photo courtesy Illinois Senate.

“If data is wrong in terms of (COVID) where does this lead us in terms of other diseases?” Villanueva asked.

Indeed, as cases of COVID and its variants ebb, questions remain on whether medical officials will be better prepared for the next pandemic.

“If you are under-measuring the impact of COVID on the Latino community, it can lead to poorly informed decisions about publicity, education, and research. That’s obviously detrimental not only to the Latino community but really to everyone in the country,” said MALDEF’s Thomas Saenz. “Inaccurate data is not helpful, particularly in the public health context.”

---

Additional reporting by Michael Izquierdo and Ivan Moreno.

Ana Arana is an award-winning investigative journalist and former foreign correspondent who reported for three decades in Latin America and Africa. She has received multiple journalism awards, including a Peabody Award, two Overseas Press Club Awards, and a Dart Award for Excellence, among others. Linda Jue is a contributing investigative editor and writer for palabra. She is also editor-at-large for the investigative site 100Reporters as well as a reporting and writing coach for the Fund for Investigative Journalism. Kyra Senese is a Chicago-based reporter. She has recently reported on the COVID-19 pandemic for the Chicago Sun-Times, WBEZ, and the Pioneer Press in Chicago.

[This story was originally published by palabra.]