More than half of American babies are at risk for malnourishment

Lauren Weber reported this story with the support of the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Markiana Richards attends an infant health class at Great Beginnings for Black Babies with her son, Priceton, in January 2018. She has accessed WIC and SNAP benefits with the assistance of the class.

LOS ANGELES COUNTY, Calif. ― The nutrition children receive during their first 1,000 days ― from conception until their second birthday ― has a profound impact on how they develop. Without the proper nutrition during that window of time, young brains will not grow to their fullest potential, diminishing the kids’ opportunities for the rest of their lives, according to public health and medical organizations.

But while the World Bank, USAID, the World Health Organization and UNICEF push to improve early nutrition among impoverished communities in developing nations, there has been much less emphasis on the first 1,000 days in the United States. That’s not to say that all is well here: Over half of the country’s infants are on nutritional assistance and the top vegetable eaten by U.S. toddlers is the french fry.

Last week, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a groundbreaking policy statement highlighting the importance, and irreversibility, of the 1,000-day window.

“Failure to provide key nutrients during this critical period of brain development may result in lifelong deficits in brain function despite subsequent nutrient repletion,” the AAP Committee on Nutrition said.

In other words, no amount of catch-up can completely fix the lost time for brain formation. Malnourishing the brain can produce a lower IQ; lead to a lifetime of chronic medical problems; increase the risk of obesity, hypertension and diabetes; and cost that individual future academic achievement and job success. The impact can even be generational, perpetuating a cycle of poverty for lifetimes to come.

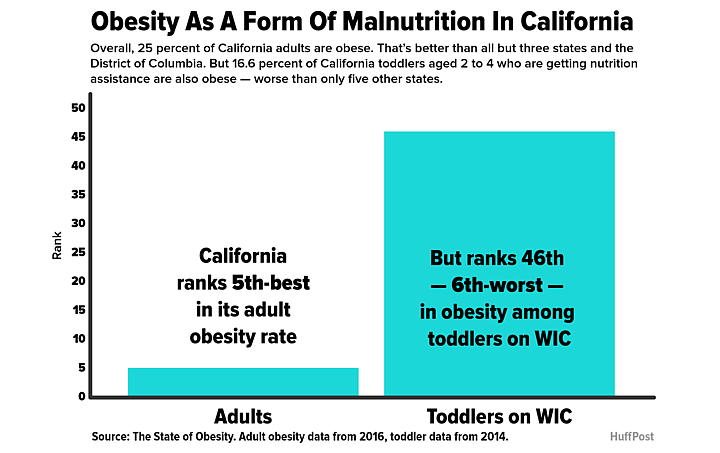

It’s unclear exactly how many kids in the U.S. are malnourished, but there’s some disturbing evidence: A quarter of toddlers don’t receive enough iron, 1 in 5 children are obese, 1 in 6 households with children are food-insecure, and over half of infants participate in the federal Women, Infants, and Children program for supplemental nutrition.

These children’s futures are at stake, said Lucy Sullivan, executive director for the nonprofit 1,000 Days, which advocates here and abroad for better early nutrition.

“The first 1,000 days matter for all the days that follow.”

Mylexus Patrick (center) examines the label of a sweet tea bottle to check for sugar during a nutrition exercise at Great Beginnings for Black Babies.

Missing Clear Guidance

Mylexus Patrick was pretty pleased with the juice box her toddler, Kyler Washington, was drinking from during a semi-monthly infant health class in Inglewood, California. After all, it contained 100 percent apple juice.

Then, one of the class instructors at Great Beginnings for Black Babies ― a nonprofit promoting the healthy growth and development of infants and children from low-income families in the Los Angeles area ― pointed out how much sugar was in it.

“Well, that kinda messed me up a little bit,” the 27-year-old pregnant mother of three said. “I came in with the little juice pouch for my son and it’s like ‘organic, no sugar added.’” They’re talking [about sugar in drinks] and I’m like ‘not my kids.’ And I read the label and I’m like oh, six of these spoonfuls, huh. OK.”

Parents face a nutritional minefield every day, but it can feel small in scale. After all, it’s just one juice box, one piece of pizza, one bag of Cheetos.

And it’s not as if the federal government has set forth any standardized dietary recommendations for children from the womb through age 2. The U.S. Department of Agriculture plans to offer guidance on that age group’s specific needs in the upcoming 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Millions of kids will have lived through their 1,000 days by then.

The challenge is to move parents today from a general understanding that nutrition is important to a recognition that poor nutrition in those early days does quantifiable damage, said Roger Thurow, senior fellow for global food and agriculture at the Chicago Council of Global Affairs and author of the book The First 1,000 Days: A Crucial Time for Mothers and Children – And the World.

Hopefully the AAP’s newfound focus can help make “1,000 days” a household term here in the U.S. as much as it is aboard, Thurow said. “Science, academics and sociologists are coming together to say, ‘Wow, this can take a toll.’”

Perhaps the first hurdle is that when Americans think of malnutrition, they think of children wasting away. But according to the AAP, malnutrition includes both undernutrition, which is a lack of macro- and micronutrients, and obesity, which is the “provision of excessive calories, often at the expense of other crucial nutrients.”

“Every pregnant woman who comes through the door wants to do better [nutritionally], but a lot of times the changes take longer than the nine months they have,” said Raena Granberry, the community outreach liaison for Great Beginnings for Black Babies.

David Henry Montgomery/Huffpost

Nearly half of U.S. women gain an excessive amount of weight during pregnancy, which in turn can lead to higher rates of obesity in children, according to the nonprofit 1,000 Days. About 1 in 5 kids in the U.S. are obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Some 1 in 4 toddlers don’t receive enough iron in their diet ― which is associated with behavioral and cognitive delays as well as anemia.

And then there’s the breastfeeding gap. Only 22 percent of U.S. infants are exclusively breastfed for the first six months, the standard that the World Health Organization recommends to ensure they get breastmilk’s special nutrition and built-in antibodies.

The AAP and other medical bodies all point to breastfeeding as key to healthy, growing babies. Yet a lack of family leave, ingrained cultural preferences and insufficient support still put this goal out of reach for many American women.

Instead, at least 40 percent of parents introduce solid foods and sugary drinks to their children much too early.

The Capital Of Food Insecurity

Nutrition in any child’s life depends on several factors: household income, cost of food, parental guidance and convenience. Los Angeles County, which has the largest population of food-insecure residents in the country, is the place to see how those things go wrong.

Los Angeles County is home to 1.2 million people who struggle to put sufficient food on the table without assistance. It also has the largest number of food-insecure children, with over 480,000 lacking proper access to food.

Experts attribute food insecurity in Los Angeles County to the high housing and living costs seen across the state. California has the highest poverty rate among states, surpassed only by the District of Columbia, when ranked by the Supplemental Poverty Measure produced by the U.S. Census Bureau.

“It’s so expensive to live here that federal poverty lines generally don’t reflect real poverty in this state,” said Elyse Homel, a senior food advocate for California Food Policy Advocates, told HuffPost.

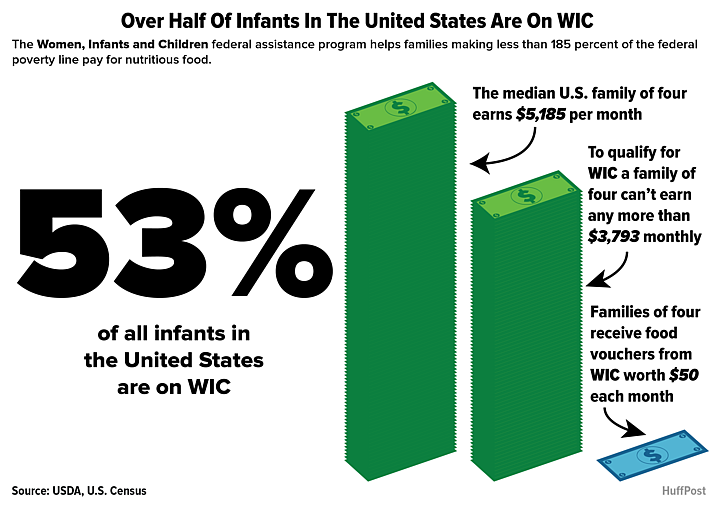

Across the country, 1 in 6 households with children faced food insecurity in 2016. To combat that, some 7.7 million people received benefits each month through the Women, Infants, and Children program, or WIC, in fiscal year 2016. To qualify, families must be considered at nutritional risk.

The program currently serves 53 percent of the country’s infants.

David Henry Montgomery/Huffpost

In Los Angeles, about 61 percent of pregnant mothers participated in WIC, which amounts to 74,800 moms, according to a California Department of Public Health report on data through 2014.

But it’s not enough. While WIC can make a dent in the problem, vouchers for around $50 a month can’t actually end food insecurity ― or completely prevent nutritional failures.

“We take nutrition for granted in the U.S. because we think there is this abundance of food and children are of course going to get fed,” said Sullivan, the executive director of 1,000 Days.

Meanwhile, she argues, the U.S. is leaving behind poor, marginalized children. “When that inequality is baked in early in life,” Sullivan said, “that has repercussions for that society later on in life, and it perpetuates the cycle of inequality.”

Options Are Limited

Ashanti Durham was attending an infant health class for the first time last month, sitting across the room from Mylexus Patrick. The slight 23-year-old was wearing a tie-dye hoodie over her burgeoning 8-months’ pregnant belly, which she kept caressing during the session.

For Durham, better nutrition meant a chance to make sure that her baby girl doesn’t suffer the same fate as her grandparents, who have a history of diabetes and high blood pressure. She sought out this class, much as Patrick had, to give herself the tools to protect her child.

“Living in an impoverished area and being raised in an impoverished area, we’re kind of tending to like the more fast foods, instead of grocery stores and creating our own meals, so I wanted to change that and see how that affected the growth of my child,” Durham told HuffPost. “I don’t want to become a statistic.”

In Los Angeles County, a metropolis littered with so-called “food deserts” filled mainly with junk food outlets, resisting the lower cost and greater convenience of fast food can be tough. Food deserts like this are part of the reason why the french fry is the most-consumed vegetable among 1-year-olds in the U.S.

“In certain parts of South LA, you have a ways to go before you get to the grocery store, but I guarantee that you have a liquor store where you can get chips and white bread or a Jack in the Box on the corner,” Granberry said.

Even with clearer guidelines ― from community health programs or the government― parents can struggle to feed their children the best food. That’s why we also need a new ethos around healthy eating, one that helps real people make better decisions, Sullivan said.

“We can’t hold up as the perfect standard that every mom is going to grow her own organic vegetables ... that’s not the reality,” she said, noting how complex family caretaking and work situations can be. “So how do we make sure moms have the right strategies when they’re pressed for time and don’t have a lot of money to maybe buy the freshest fruits and vegetables?”

It’s a challenge that Celine Malanum, a middle-class mother from Long Beach, California, who has two girls and is pregnant with her third child, thinks about all the time.

“There’s tons of fast food around ― you can get two large pizzas for $8 and that will feed everybody and give my husband lunch for two days,” the certified lactation education counselor said. “And I resort to that.”

Those impossible standards detailed by Sullivan can be overwhelming for parents, Malanum added.

“Parents are built to fail ― it kinda sucks and it’s not fair,” she said. “There’s the shame of it, too, if you can’t do those things for your kid.”

Some 10 to 20 moms come twice a month to the infant health class called Sister to Sister, where topics include everything from nutrition to child support and life insurance.

Tackling The Knowledge Gap

Sullivan attributes the widespread ignorance about the importance of the first 1,000 days in part to a lack of standardized nutritional advice for children under 2. Her nonprofit will soon be launching a new initiative, working with high-level government experts and health professionals, to pull together practical resources for parents on the what, when and how to feed in the earliest years of a child’s life.

They aim to provide “a little bit of a guidebook, a little bit of the road map on what’s the best to feed your babies,” Sullivan said.

In the meantime, the AAP is urging pediatricians and child health care providers to place a renewed emphasis on breastfeeding, nutritional programs and interventions, and guidance that increases parents’ “awareness of which foods are ‘healthy,’ not just as alternatives to unhealthy or junk food but as positive factors targeting optimal development.”

For Mylexus Patrick, it all comes down to making those changes early. Reaching over her pregnant stomach to wrangle her son’s pants, she says she wishes more people would think about their child’s nutrition instead of taking it for granted.

“They have to take care of these bodies until they get older, and while they’re young, their parents are in control of that,” she said. “If you’re just letting them run around eating a bunch of crap, they’re probably going to have crappy bodies by the time they’re teenagers and try to fix it, like we all did, later on in life.”

Which, as the science shows, may be too late. Missing out in those first years can mean a “life sentence of underachievement,” Thurow said.

“That makes the climb out of poverty so much harder.”

[This story was originally published by the Huffpost.]

[Photos by Sara Terry/Huffpost.]