New Law Aims to Expand Access to HIV Prevention — But Will It?

This article was produced as a larger project by Larry Buhl for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2019 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in his series :

Will Pharmacist Resistance Hamper Law to Expand Access to HIV Prevention Meds?

Pharmacies Grapple With Red Tape as States Try to Allow Pharmacists to Prescribe PrEP

Back in March, Quadeer Jones, a 23-year-old actor in Los Angeles, decided to get pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, to protect himself from HIV when having sex. He made an appointment at the Los Angeles LGBT Center to get PrEP medication, the antiretroviral Truvada, traveling more than 30 miles. Once he arrived at the center, the process was relatively easy. “I had to schedule an appointment for rapid HIV testing,” he says. “They said I was negative. I got my prescription and meds and I was out the door in about an hour.”

Jones, a New York transplant, had an easier time getting PrEP than most people, and his situation is even more unusual because it was his very woke father who told him about PrEP after hearing about it on a TV commercial. Many people who want PrEP, at least those who aren’t close to an LGBT-friendly clinic, might have trouble getting a doctor to prescribe PrEP, or finding one who even knows what it is. And then they might not find a pharmacy with Truvada, or a newer drug called Descovy, in stock. In many parts of the country, paying for PrEP can be another hurdle, though thanks to Medi-Cal and the state PrEP Assistance Program, the meds are free or nearly free for most Californians. Regular lab tests for people on PrEP long-term are often an out-of-pocket expense.

These hurdles cause unnecessary delays in obtaining what can be lifesaving medication. Approved by the FDA in 2012 to prevent HIV, Truvada — and now Descovy — provides up to 99 percent reduction in HIV risk for HIV-negative people, when taken as directed. More than just the pills, PrEP is a regimen that also requires regular HIV tests and testing for kidney functions.

Both medications can also be used in post-exposure prophylaxis, known as PEP — taken, along with other meds, like “morning after” medication for people who may have accidentally exposed themselves to the virus. But waiting several days for a doctor’s visit, another few days for HIV test results and maybe another day for insurance preauthorization can make PEP unusable. PEP can be obtained at some emergency rooms or urgent care clinics — that is, if ER doctors are willing to provide it.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that more than 1 million people in the U.S. could benefit from PrEP, but prescriptions for it have been underwhelming, particularly among the most vulnerable populations — young gay and bisexual men of color and trans women. Since it was approved to prevent HIV in 2012, only 135,000 prescriptions had been filled in the U.S. by October 2019. AIDSVu, a collaborative research project between Emory University and Gilead Sciences, the maker of the meds used for PrEP, estimates there are approximately 28,000 PrEP users in California, although the data do not include closed health systems like Kaiser Permanente. Still, PrEP use is significantly below the need: The California Department of Public Health estimated that between 221,528 and 238,628 Californians would meet the criteria for PrEP. According to the CDC, HIV-negative people who are sexually active or using IV drugs may be at risk of contracting HIV.

“Demedicalizing” protection against HIV

Last year California lawmakers aimed to boost the use of PrEP and PEP by removing some of the barriers to obtaining them. The passage of Senate Bill 159 (SB 159) made the state the first in the nation to allow pharmacies to sell a 60-day supply of Truvada or Descovy without a doctor’s prescription. The bill also eliminated preauthorization requirements for the meds.

The goal of SB 159, co-sponsored by California Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) and Assemblymember Todd Gloria (D-San Diego), was to have anyone who needs the medication be able to walk into any pharmacy and get it, without a doctor’s appointment, on the same day. The provision to nix insurance preauthorization took effect January 1. The other provision — pharmacy sales without a doctor’s prescription — has been taking a little more time to implement.

Mitchell Warren, Executive Director of AVAC (AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition), says SB 159 will help more people have access by partially “demedicalizing” access to meds. “We distribute contraceptives in ways that are demedicalized. You don’t have to run the gamut of nurses, etc. We are at the beginning of looking at demedicalized delivery [of PrEP] and that is very important.”

Disparities in PrEP access

As a product of a data fellowship from the University of Southern California Annenberg School of Journalism, this story is the first of a two-part series exploring how the law could work as intended, what regions of the state might benefit the most — the PrEP “deserts” — and what stumbling blocks could keep it from succeeding. Some of the biggest stumbling blocks, though, are not a fault of the law, but have more to do with the disparities inherent to health care in America, including scarcity of facilities in many communities, medical mistrust and, particularly important for a law aimed at preventing HIV, stigma — both on the part of patients and providers.

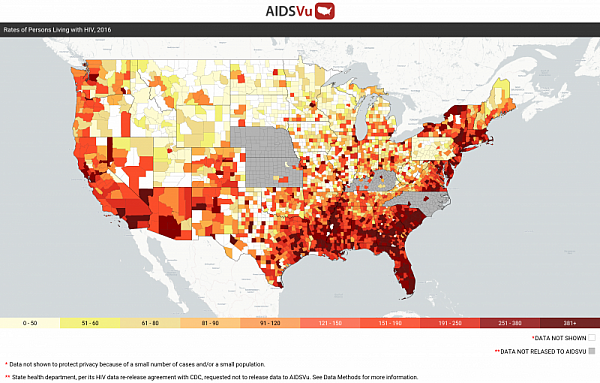

Map by AIDSVu. Note: Alaska, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico don’t have counties from which to draw data.

Several California counties are among the highest in the nation for new HIV diagnoses.

In Imperial County, 29 of every 100,000 people were newly diagnosed with HIV in 2017, according to the latest statistics available. However, that’s far below Fulton County, Georgia, with 69 out of 100,000 and Stewart County, Georgia, with a whopping 130 cases per 100,000. The Deep South has been a hotbed of HIV infections for years. As far as PrEP use, California is doing a bit better than the South, thanks partly to the statewide PrEP Assistance Program, which is run by the California Department of Public Health Office of AIDS and which provides financial assistance with PrEP medication and related expenses.

But there are significant differences in PrEP use from county to county in California. Advocates tell Capital & Main that differences have much less to do with paying for PrEP than with the number of places a person can get it, stigma and knowledge that PrEP exists as an effective HIV prevention tool. In short, PrEP use is highest where there is what advocates call “a culture of PrEP.” On that measure, one county, San Francisco, is succeeding. Most other counties are severely lagging.

A tale of two counties

San Francisco County, which shares the same boundaries as the city, is compact and diverse. With fewer than a million people, San Francisco is one of the most densely populated major American cities.

San Francisco’s rate of PrEP use for all age groups is the highest in the state by far; in 2018, 644 of every 100,000 residents were using PrEP; that dwarfs all California counties, including one with a much larger population, though spread out: San Bernardino.

Bordered by Nevada and Arizona to the east, San Bernardino County is home to more than 2 million people across more than 20,000 square miles of high and low desert and mountains, the largest county outside of Alaska. It’s more than half Latino and has a nearly 15 percent poverty rate.

In addition to having one of the lowest overall rates of PrEP use of all data available, at 35 out of every 100,000, San Bernardino County also has one of the lowest use of PrEP based on the estimated number of people who could benefit from it (PrEP-to-need ratio, or PnR), and the lowest PnR in California for people under 24 years old. The map below shows that in 2018, for every person newly diagnosed with HIV in San Bernardino County, there were 2.82 people using PrEP. For those under 24, there were 1.63 people on PrEP. By contrast, in San Francisco County, the numbers were 20.33 and 11.34.

There are a couple of reasons for this disparity, according to Michael Chavez, a case manager at the Foothill AIDS Project (FAP) in San Bernardino. “There is no LGBT center in San Bernardino County,” he says. “[Foothill AIDS] is point-of-contact for all communities, but the ones who come here usually have HIV.”

Chavez adds that the number of young men who come to FAP for any reason is very low, and the project doesn’t yet have a clinic to provide PrEP and PEP, though that’s in the works. Right now, people who want PrEP are likely to drive 50 miles west to the L.A. LGBT Center, or APLA Health, he says

Chavez notes that the median income is lower than in L.A. County, and the amount of information about HIV and PrEP is harder to find. “If they don’t see an ad on TV about PrEP, they probably won’t know about it,” he says.

In theory, any doctor in California, or the country, could prescribe PrEP, but that doesn’t mean they do. According to data from the CDC, the number of locations to get a PrEP prescription in San Bernardino County — but not necessarily obtain the medication — is eight: two doctors, one Kaiser Permanente facility, one CVS MinuteClinic and four public clinics. That’s compared to 50 providers in San Francisco County.

In listening sessions with young, sexually active cisgender men and trans women conducted in Los Angeles, a common theme was that primary physicians didn’t know what PrEP was, and many of those who did know wouldn’t write a prescription. Some participants even recounted being “slut-shamed” for being sexually active. More than one participant said doctors and nurse practitioners said of their desire to have gay sex, “You’re not a real man.” Health care workers in county facilities were particularly prone to these sentiments. This, in 2020.

SB 159, in theory, is a workaround for culturally conservative physicians — that is, if there are enough non-culturally conservative pharmacists willing to opt in. When the law is working as intended, it will go like this: Any Californian could go into a pharmacy and ask for PrEP or PEP, get the required HIV test — if they haven’t had one in the past seven days — on the spot, and walk out with a 60-day supply of PrEP or a 28-day supply of PEP. As part of that service, the pharmacist would hand off the customer to a doctor for ongoing care and lab tests.

Chavez says SB 159 will eventually expand access to PrEP, but doubts it will create a mass rush to pharmacies without a public awareness campaign; the law didn’t set aside money for publicity. And Chavez, who manages FAP’s specialty drug program, says pharmacies that provide Truvada or Descovy for PrEP and PEP — or even provide these meds for HIV treatment — are few and far between in the county.

“I could walk out my door and I would not be able to find an HIV drug in a 10-mile radius,” Chavez tells Capital & Main. “You can order it by mail, but that won’t help if you need it right away, like PEP.” In addition, the pharmacy might prove intimidating for potential customers. “People don’t want to walk into a pharmacy to get PrEP and have other customers hearing that they need PrEP.” Some young men who participated in listening sessions for these stories also worried about getting “attitude” from their pharmacists like they have from primary care doctors and nurse practitioners.

Unlike in San Bernardino County, PrEP is everywhere in San Francisco. An LGBT mecca for nearly a century, San Francisco was an epicenter of HIV from the early years of the epidemic. So, as it was one of the first areas to address the ravages of AIDS, it also has been aggressive in preventing HIV, the virus that can lead to AIDS. Now, it has a Getting to Zero initiative, as do several other California cities, which is expanding PrEP access and encouraging people in STD clinics to consider PrEP.

“There is community norm to be on PrEP here,” says Hyman Scott, Clinical Research Medical Director for the San Francisco Department of Public Health. “San Francisco has a very empowered and well-resourced community able to access PrEP. The motto is ‘Every door should be the right door’ to PrEP. We do hear this in focus groups a lot if it comes down to who in your social network takes it and are they supportive of it. And the provider culture is supportive here and that is not true everywhere.”

Too early to determine its effectiveness

SB 159 was written to make getting PrEP anywhere in the state as easy as it is in San Francisco. According to the California Pharmacists Association, however, no pharmacist has yet completed the required training to sell PrEP under the law, and it isn’t even clear which pharmacists will agree to sell it. SB 159 is an opt-in law, not unlike a 2016 law allowing sales of birth control without a prescription, a worrisome comparison given the initial resistance of pharmacists. However, PrEP and PEP require ongoing testing for kidney functions, as well as regular testing for HIV, which makes it a slightly more complex service than providing birth control.

Even the law’s strongest proponents, including Craig Pulsipher, Associate Director of Government Affairs for APLA Health, admit that the law won’t mean that people can get PrEP and PEP at any pharmacy right away. Pulsipher says that while he’s optimistic that SB 159 will result in more people using PrEP and PEP, the bill was never intended to be the “be-all end-all solution.”

“Even with the steps we have taken to increase access and reduce financial barriers, significant challenges remain that are more difficult to address, such as stigma, systemic racism and lack of culturally competent providers,” he says. “We have much more work to do to address these issues and a host of other factors that impact a person’s willingness and ability to take PrEP.”

In part two of this series, I will explore some of these issues, including why pharmacists might decide not to prescribe PrEP and PEP, how the lack of free testing services around the state could undermine sales, and how health disparities and health care incentives could determine the success or failure of SB 159.

[This story was originally published by Capital and Main.]

// //