Operating Within the Confines of a Racist System

This story was originally published in Black Voice News with support from the 2022 California Fellowship.

Black Voice News

As the Founder and Director of Diversity Uplifts, a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving the well-being of women, birthing people and families, Dr. Sayida Peprah-Wilson is always thinking about allyships and partnerships with philanthropic organizations and insurance companies that can help expand doula support and coverage.

“How do we create a sustainable model where every Black woman can have a doula whether or not Medi-Cal covers it?” Dr. Peprah-Wilson asked. “Because every Black woman doesn’t have Medi-Cal.”

Dr. Sayida Peprah-Wilson speaks to the crowd about mental health and wellness during a “My Hair, My Health” event in Riverside, CA on August 28, 2022 (Aryana Noroozi for Black Voice News/CatchLight Local)..

In 2019, 28% of Black Californians were covered by Medi-Cal and 46% were covered by insurance provided through their jobs, according to a report by the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF).

The systemization of doula services will not change what doulas do, who they are or who they set out to serve, Dr. Peprah-Wilson concluded. Before she knew there was a name for it, she was always a doula — supporting friends and family with their reproductive and birthing needs, from being at her childhood friend’s bedside during birth, to escorting friends to abortion clinics.

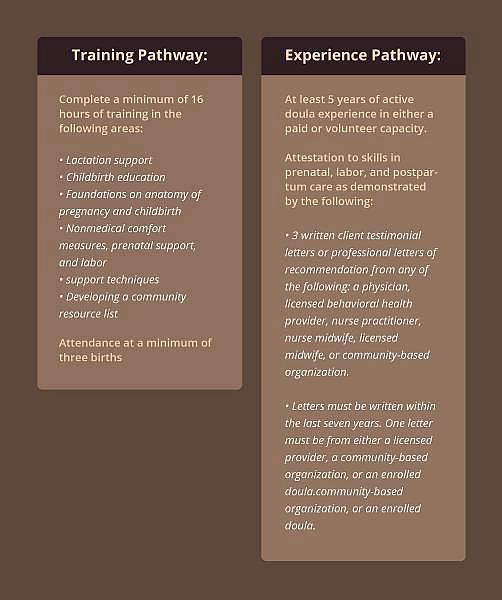

Under the current draft of the California State Amendment Plan, there are qualifications in place that lay out criteria for doulas to be reimbursed, such as completing basic Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) training and completing three hours of continuing education in maternal, perinatal and infant care every three years. Other qualifications will be based on “pathways” developed by the benefits team and workgroup members.

The Training Pathway requires doulas to complete a minimum of 16 hours of training across several areas including foundations on anatomy of pregnancy and childbirth, hands-on support with clients and “supplemental training in trauma-informed care…cultural sensitivity or competency or implicit bias or anti-racism and social determinants of health for birthing populations.”

The Experience Pathway requires doulas to have at least five years of doula experience in either a paid or volunteer capacity, evidence of skills in prenatal labor and postpartum care demonstrated by three written client testimonials and three professional letters of recommendation from a physician, pediatrician, licensed behavioral provider, nurse practitioner, nurse midwife or community-based organization.

CHJ · Dr. Sayida Peprah-Wilson_1

During a stakeholder meeting in April where these requirements were laid out, many doulas on the call objected to these requirements, citing they had been practicing doula work for decades and their care had already been quantifiably proven to have successful outcomes. One doula on the call who has been practicing for over 40 years and served over 1,000 births objected to the requirements —

“running this spiritual work through a patriarchal [filter]…is offensive,” they commented.

There are a variety of certifications and training for birthworkers that are developed by community-based organizations and birthing organizations such as the DONA Approved Birth Doula Training Workshop, but there are no standardized certifications by just one entity for this work, given the origins as a cultural and community practice.

“My dad always says this to me, and I find it to be very healing for my mind when I get frustrated with systems: If you’re operating on a plantation, you cannot expect the plantation master or any of the people holding up systems, to give you a key to freedom to support you in your advocacy for complete self-determination,” Dr. Peprah-Wilson recited.

2022

American Rescue Plan Act of 2021

A provision in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 gives states a new option to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage to 12 months via a state plan amendment (SPA).

Department of Health Care Services

The Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) expected to launch Doula Services as a Medi-Cal Benefit, but were unable to finalize the SPA by the deadline.

2023

Doula Services in 2023

DHCS will add Doula services as a covered benefit starting January 1, 2023.

Overcoming a history and legacy of medical maltreatment

As more reports, articles and commentaries arise regarding the lack of equitable care in the healthcare system as it relates to Black birthing people, their poor experiences within hospitals and fatal outcomes, Sharla Fett, a 19th-century historian and professor at Occidental College, explained that such patterns of disparity will not be adequately addressed until medical institutions acknowledge the racialization of medicine, implicit bias in medicine and institutionalized racism.

In an article written by Fett and Dr. Deirdre Cooper Owens, the authors discuss Black maternal and infant health in relation to the legacies of slavery that continue to influence and uphold structural racism as it sustains the disproportionate rate of Black pregnancy-related deaths.

“How does a community learn to trust doctors whose forefathers were interested only in repairing and restoring Black women’s reproductive health so that slavery could be perpetuated?” The authors questioned in the article. “How does the medical profession unlearn a pattern of dismissing Black women’s self-reported pain when that pattern is rooted in centuries-old soil?”

Fett explained that one of the steps to answering these questions and moving toward equitable care as a standard practice in medical institutions is understanding and confronting the historical roots of medical racism.

“If we understand that medical racism for centuries held that people of African descent couldn’t feel pain the way that people of European descent did…it can help, I think, to mobilize the change today and highlight the fact that some of these inherited patterns or legacies are still persisting,” Fett explained.

These “inherited patterns” have prevailed throughout American history as documented in the 1985 Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health (“Heckler Report”), one of the first extensive reports that documented racial disparities in the U.S. healthcare system by medical personnel. Recently, a 2016 study found that Black patients are less likely to be adequately treated for pain compared to White patients, and if they are treated, they are given a lower pain treatment.

Inequitable treatment of Black patients extends to Black maternal health. A 2018 state-wide study by CHCF and EVITARUS called “Listening to Black Mothers in California” examined responses from more than 2,500 Black women who shared their poor experiences within the healthcare system.

The study found that nearly one-third of Black mothers reported that “they did not feel the delivery room staff encouraged them to make decisions about their birth progression.” The report also found that Black women were more likely than White women to report feeling pressured to have medical interventions during labor and delivery.

“Seventeen percent of Black women reported that they felt pressured to induce, and 15% said they felt pressured to use an epidural for pain relief,” the study noted. “Black women also reported feeling pressured to have a cesarean birth almost twice as often as White women (18% compared to 9.5%).”

Fett explained that doulas are a large part of the support system that will overcome such inequities, what scholar Dána-Ain Davis labeled as “obstetrical racism” — a reference to the mistreatment of birthing people in labor or during their birthing experience based on the patient’s race which “influences medical professional’s perceptions.”

In her article, “Obstetric Racism: The Racial Politics of Pregnancy, Labor, and Birthing,” Davis examines Black birthing stories and encounters fueled by inherent racism that led to poor maternal outcomes, and argued for increasing the presence of birthworkers (doulas and midwives) to “mediate obstetric racism and stratified reproductive outcomes.”

Davis’s article summarized that the work being done by doulas and midwives is “disrupting obstetric racism” by employing a reproductive justice approach.

“Resisting the disempowering medicalization of birth, midwives and doulas said they provided care to help reduce premature births, and to reduce infant and maternal mortality and morbidity,” the article noted.

One key aspect of doula work is empowering clients to take charge of their birthing experiences by ensuring that they advocate for themselves, their health and their babies. Karen Sykes, a doula and an associate pastor in the Inland Empire, explained that her desire to become a doula was fueled by her own experience giving birth within a hospital setting where she had no autonomy over her body.

“I want to make sure that the women coming up, especially Black women, women of color, understand what their rights are, what they’re privileged to, what they can say no to, what they can say yes to, so that they are empowered to make their own choices about how they birth,” said Sykes.