It Begins Like This

This story was originally published in Black Voice News with support from the 2022 California Fellowship.

Black Voice News

The disproportionate rate at which Black birthing people die as a result of pregnancy-related causes in the U.S. is no secret. While California may have a lower rate of pregnancy-related deaths, California is not exempt from the problem. Black birthing people in the state still experience a higher rate of death than any other race, but Black doulas have been working to reduce that rate by prioritizing Black health, supporting families and advocating for change. This series explores the work of doulas, the families they support, regional and state-wide efforts to expand doula access as part of the solution to this historical disparity.

When DeShawna Wright, 31, described how talkative and joyful her three-month-old daughter, Noni, is, she had a warm smile. Wright’s friendly and welcoming nature was on full display when she introduced herself by the nickname, Shay, during a Black birthworkers event in San Bernardino, CA, in April.

Hosted by an Inland Empire-based organization, the Sankofa Birthworkers Collective of the Inland Empire, the event was held during Black Maternal Health Week, a week that seeks to bring awareness of the state of Black maternal health and mortality in the U.S. Led by an eclectic group of birthworkers — from lactation consultants to midwives to maternal mental health professionals — the collective highlights Black birthing people at the center of their vision to “foster wellness in the Black birthing community through direct services, education and advocacy.”

In the U.S. Black pregnant people are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than White pregnant people.

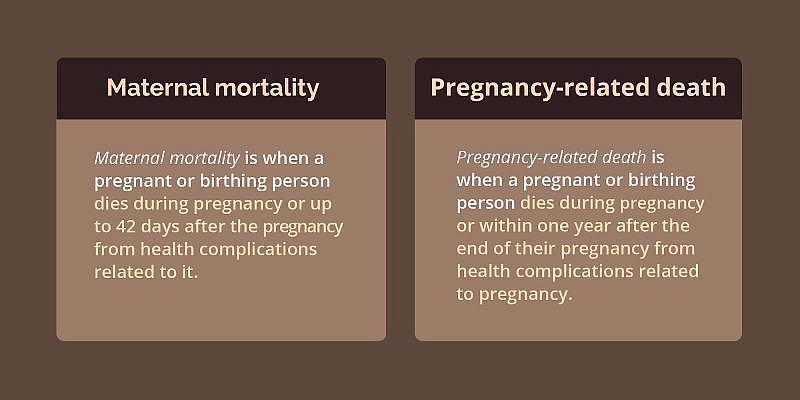

Maternal mortality is when a pregnant or birthing person dies during pregnancy or up to 42 days after the pregnancy from health complications related to it. Pregnancy-related death is when a pregnant or birthing person dies during pregnancy or within one year after the end of their pregnancy from health complications related to pregnancy.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) noted that roughly 80% of pregnancy-related deaths are preventable — a percentage Black doulas aim to improve through education and advocacy.

Wright heard about the birthworkers event through her own doula, Chantel Runnels.

A doula is a non-medical, trained professional who provides physical, emotional, spiritual and mental support to a birthing person before, during and after childbirth with the goal of supporting a healthy and safe birthing experience. Doula care covers a wide range of services including supporting birthing people and their families with in vitro fertilization, lactation, prenatal and postpartum care, and even abortions.

Left: DeShawna “Shay” Wright, a hairstylist in San Bernardino county, gave birth to her daughter Noni in February 2022 with the support of a doula. Right: Noni, Wright’s daughter, grins as her mother takes her picture (Image courtesy of DeShawna Wright).

“The funny thing about my doula was that I met her a week before my due date,” Wright explained. She applied to receive doula support a month before her pregnancy through a local initiative called the Doula Access Program. She was paired with Runnels just before her initial due date on February 22, 2022.

The day before she expected to give birth, Wright’s doctor called to cancel her appointment because he was delivering other babies. With her due date changed, Wright called her doula to give her an update.

DeShawna “Shay” Wright is pictured with her husband, Dr. Louis Wright, and two children, Noni and Layden Wright at the beach (Image courtesy of DeShawna Wright).

Wright’s labor was induced two days later on February 24 and Runnels provided virtual support during her labor and then provided support for six weeks postpartum. Despite only meeting a short time before her due date, Wright recalled how motivational and supportive Runnels was during her labor, and how Runnels encouraged her to create a comforting and calming atmosphere to give birth.

“She just inspired me because I didn’t do that with my son,” Wright explained. “I didn’t have any music. I didn’t have aromatherapy. I didn’t put myself in a space of relaxation.”

Wright also has a three-year-old son named Layden. After the birth of her son and prior to giving birth to Noni, Wright’s pregnancy journey had been difficult. Before conceiving her daughter, Wright had two miscarriages and an ectopic pregnancy, a condition where the fertilized egg grows outside the uterus. With this pregnancy, Wright changed her diet, her mindset and eventually sought the support of a doula.

Wright had to explain to her husband that her doula wasn’t going to deliver Noni, but would be there for emotional, mental and spiritual support. After showing him a handful of Youtube videos about what doulas offer, he was on board and supportive of having a doula.

“I’m glad I had her at my fingertips on my phone, because he was working while I was in labor. He was in the room, but he was working remotely — literally helping someone with their class schedule while I’m in labor,” Wright said. Her husband, Dr. Louis Wright, is a college counselor. She joked that his students could hear her moaning and groaning. “It was so disrespectful.”

Listen to DeShawna Wright talk about her experience with her doula.

Wright pointed out the differences between giving birth to her daughter and her son, like how she implemented aromatherapy, breathing exercises and calming music during labor as suggested by Runnels. She also credited the resources in the Inland Empire that she had at her disposal as contributing to an improved pregnancy experience.

Supporting Black Infants and Mothers

While pregnant with Noni, Wright participated in the local Black Infant Health Program through Riverside and San Bernardino Counties. Initially launched by the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) in 1989 to improve Black maternal and infant health and mortality throughout the state, the program operates across several counties where over 90% of Black births occur.

In April, during Black Maternal Health Week, Stephanie Bryant, Program Chief of the Maternal Child Adolescent Program at Riverside University Health System – Public Health and director of Riverside County’s Black Infant Health Program discussed the benefits of the program and its impact.

1900’s

“Granny Midwives”

Black women, commonly referred to as “Granny midwives,” practiced midwifery in the rural South, a legacy that can be traced back to when Black women, who were enslaved, were trafficked to the U.S.

1917

Assembly Bill 1375

California authorizes midwifery as an independent profession under an amendment of the California Medical Practices Act (Assembly Bill 1375).

1933

Maternal Death Reporting

All states begin reporting maternal deaths for the first time, and the mortality rate for Black mothers (1,000 deaths per 100,000 births) was 1.8 times the rate for White mothers (564 deaths per 100,000).

1949

Illegal Midwifery

The state of California stops issuing certificates to practice midwifery, essentially making the practice illegal.

1974

Senate Bill 1237

California passes Senate Bill 1237 which requires Certified Nurse Midwives to practice under the supervision of an obstetrician.

1989

Black Infant Health Program

California Department of Public Health (CDPH) launches the Black Infant Health Program (BIH) to improve the state of Black maternal health and infant health.

“The focus is on building that social support network, addressing issues in terms of mental health and stress management. And then also really teaching moms about empowerment,” Bryant explained, including, “How to advocate for yourself when you’re working with your provider, what a healthy pregnancy should look like.”

While Wright attended weekly group sessions through the program, she mentioned wanting a doula and being interested in having a home birth — but, both her husband and her mother were against the idea. Wright was able to get partnered with Runnels through her health provider, Inland Empire Health Plan (IEHP).

Doula Services Come to the Inland Empire

In 2018, IEHP and Riverside Community Health Foundation (RCHF) formed a partnership to launch the Doula Access Program, a local pilot that reimburses doulas for services provided to IEHP members.

An initial call to the community led to Dr. Priya Batra, Senior Medical Director at IEHP and OB/Gyn, and Dr. Shené Bowie-Hussey, RCHF Vice President of Health Strategies and a doula, meeting and developing a plan.

Launched in January 2019, the doula pilot program has since evolved and grown to support hundreds of pregnant people and their families throughout the Inland Empire. The process of securing a doula begins with a family contacting RCHF who then performs an intake procedure to collect information about the family and then matches a family with a doula.

Attendees take notes as they participate in Black Community Doula Training hosted by Riverside Community Health Foundation (RCHF) as part of the Doula Access Program in July 2022. Eleven participants graduated from the training (Image courtesy of RCHF).

Doulas who are contracted with the program undergo orientation between RCHF and IEHP to review their background and training. The program also provides training on the protocols and standards of doulas versus providers. Now in its third year, the program has worked out some kinks and has developed more efficient ways of partnering families with doulas.

“There are a lot of doula trainings nationwide, but the trainings we offer are a standout experience for many reasons: [First,] it is focused on our immediate community. We provided multiple disciplinary professionals who are currently serving families in the community,” said Doula Access Program Coordinator and Senior Health Educator Deidre Coutsoumpos.

“[Second,] this is a love offering to the Inland Empire. The staff and the participants are committed to closing the gaps in maternity care for our local community members. [Third,] our hands-on, experiential training speaks to multiple ways of learning to prepare participants fully to serve birthing families.”

The program includes doula support for three prenatal visits, the birth and three postnatal visits. The Doula Access Program currently contracts 43 doulas and has managed to retain doulas by employing them as independent contractors and implementing doula trainings that address gaps in care such as hosting trainings for doulas who are blind and training for doulas who primarily speak Spanish.

As part of the Doula Access Program, Riverside Community Health Foundation (RCHF) hosted a Spanish Doula Training in August 2022 and 9 participants graduated (Image courtesy of RCHF).

“Our original goal was [to serve] 100 families. We had 100 inquiries, probably the first six weeks or so,” Dr. Bowie-Hussey said. “And so we’ve amended our contract three times now. It’s a very successful program.”

After surpassing their initial goal of helping 100 families, there are currently 462 families enrolled in the Doula Access Program. From January 1, 2019 to now, there have been 371 births. The program’s new goal is to serve 500 families by the end of 2022.

The Doula Access Program is funded by the IEHP and compensates doulas with a reimbursement rate of $1,100 for the services they provide.

“The rate the state is proposing under [Medi-Cal] is pretty similar to what we’re paying. However, their package includes more visits for that same rate,” Dr. Batra clarified. “We really wanted to learn from other pilots in Medicaid elsewhere in the country which had reimbursements rates that were much lower and had not found doulas that wanted to participate, and had not really attracted clients either. So, we did not want to be in that position.”

Doulas aren’t typically covered by commercial or private insurance companies despite research providing evidence on the impact doulas have on the health outcomes of Black birthing people, such as reducing the cesarean sections and lowering anxiety and depression during labor which can lead to deadly outcomes. With doula pilot programs like the Doula Access Program, doulas are able to provide services to birthing people in need while also being compensated at an equitable rate.