Part 2: Analysis reveals disparities among death rates in California county jails

This story is produced as part of a larger project by Matthew Brannon, a participant in the 2020 California Fellowship.

His other stories include:

Part 1: Dying Inside: Why are more deaths happening in Shasta County Jail custody?

Callout: What do you want us to know about jails in Northern California?

Part 3: With jail deaths on the rise, California counties look to improve

Part 4: Shasta County Jail: Two important areas of policy to understand

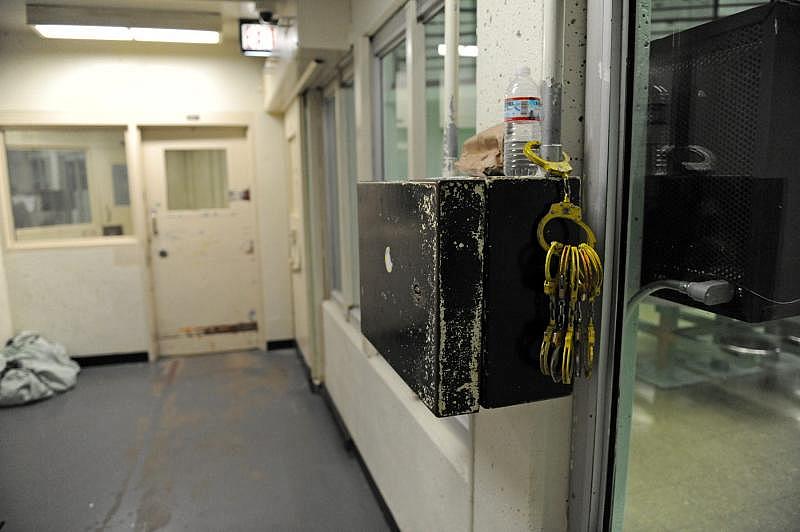

JAY DUNN/THE SALINAS CALIFORNIAN

Every year, California counties spend more than $4 billion dollars to incarcerate possible offenders in county jails. The facilities aren't expected to be luxurious. They are, however, constitutionally obligated to protect people from harm.

That doesn’t always happen. From 2005 to 2019, about 1,960 people died in the custody of California county jails. Most of these jails operate with relative independence under elected sheriffs, some with little local oversight. Differences in how counties run their jails become more obvious when comparing their rates of jail deaths.

To better understand disparities, the Record Searchlight reviewed 53 of California’s 58 counties with available data. That review showed some jails have death rates double or triple that of their neighbors or other jail systems of similar size.

The analysis comes after the Shasta County Jail saw three deaths in custody in September of 2019. State data shows Shasta ranks within the top 12 counties of the 53 reviewed in its jail death rate, with about 13 deaths in county jail custody per 100,000 bookings — a metric that allows for a per-capita comparison among jail systems of different sizes.

Over the past 15 years, Shasta reported about twice as many deaths in jail custody as Santa Cruz County (12), despite locking up roughly the same number of people during that timespan.

Another county in California’s North State, Tehama, ranked No. 1, averaging 26 deaths per 100,000 bookings, more than double the state median of about 10. Trying to answer why is a separate challenge. Jail administrators weren’t able to offer clarifying theories on disparities like those aside from suggesting demographics could play a role.

“I’m certainly going to take a very hard look at what the causes of death are and figuring out a way how we can take some preventative action,” said Capt. Gene Randall, who in January began overseeing the Shasta County Jail for the sheriff's office.

Trying to determine the avoid-ability of any individual death can prove difficult.

In California, there haven’t been any published studies trying to make sense of death rate disparities among county jails. So it can be hard to answer definitively why a place like Tehama County has four times the jail death rate of neighboring Butte County, which averages about 7 deaths per 100,000 bookings. Especially since, outside of jail, Tehama has lower death rates than Butte, according to state data.

Still, experts say there are some characteristics that jails with high death rates have in common.

One of those experts is Jeff Schwartz, who holds a doctorate in psychology and has spent decades developing training guides for jails and prisons. He's worked as an expert witness on wrongful death cases, consulted for the California legislature and currently serves as a federal court monitor for two Southern California jail systems.

//

“Where a jail has a number of deaths — some of which are questionable or they have a high number compared to their population — that frequently is a result of systemic problems,” Schwartz said. “It’s not just one thing. It’s failure to supervise, and staff who don’t have much training on key issues like suicide prevention or medical emergencies ... and it goes on."

Michele Deitch, a Texas attorney, corrections consultant and lecturer at the LBJ School of Public Affairs, said differences in staffing, training, attitude and services “can make an incredible difference” in how people experience the jail setting.

As the Record Searchlight looked into Northern California counties with high rates of jail deaths, complaints of inadequate medical care and low levels of supervision, often driven by staff shortages, surfaced in many of the jails with the highest death rates.

Here’s how they connect:

Medical care issues in jail

James McMillan, 77, had been working on his late mother’s property in Shasta County in March 2019 when firefighters accused him of a burning violation. McMillan, an attorney from San Diego, refused to sign the citation, was arrested and taken to jail.

By the end of his stay, he felt like a victim of elder abuse. According to his lawsuit, a jail nurse threw his medications in the trash because they weren’t in an original bottle. When his cousin brought them in an original bottle, McMillan said the deputy in charge refused them. McMillan claimed he went more than a day without diabetic medication and began hallucinating by the time he left the facility.

“They were negligent. They just ignored my condition,” McMillan said. “I had a professional doctor prescribe medication for heart problems — they could kill me — and they just blew me off.”

Both Wellpath and Shasta County jail officials have denied McMillan’s claims of mistreatment in court. The case is ongoing.

Like many jails, Shasta County doesn’t provide medical services to jail residents directly. It contracts through a company called Wellpath, one of the nation’s largest for-profit providers in corrections.

Schwartz said the quality of jail health care providers can vary, including some that do “an absolutely awful job.”

“There is a built-in tension between profit level and quality of care,” Schwartz said. “And if the quality of care is sacrificed, usually, then you can quickly get into situations where inmate lives are at risk.”

Wellpath's history is packed with litigation and claims of poor care. The company got its name in 2018 when two large jail health care firms merged — Correctional Medical Group Companies and Correct Care Solutions. Since 2003, the latter has been sued at least 1,395 times in federal court, including wrongful death suits, according to the Project On Government Oversight, a watchdog organization and offshoot of the National Taxpayers Union.

"If the quality of care is sacrificed you can quickly get into situations where inmate lives are at risk.” - Jeff Schwartz, who holds a doctorate in psychology

When poor care contributes to a death, county taxpayers end up footing some of the cost to settle the claim. Lake County residents learned that in 2018 after a woman hanged herself in jail. The county agreed to pay $2 million as part of a wrongful death lawsuit. The suit showed, according to the woman's attorney, that California Forensic Medical Group (part of Correctional Medical Group Companies) was using lesser-trained vocational nurses to make important medical and mental health decisions.

Shasta County is currently defending its own wrongful death suit with California Forensic Medical Group, stemming from a 2017 incident in which a man overdosing on methamphetamine was booked into jail and found dead within two days.

In that case, the man’s family contends the jail and California Forensic Medical Group staff knew he was suffering from serious medical needs and were “deliberately indifferent” — denying him medical care and resulting in his death, according to court documents.

The medical group and jail officials denied those claims, and the suit is still playing out.

Talk of deficient medical care at the jail is not new. In 2015, a consultant surveyed 32 Shasta County Jail employees. Only 28% said there are adequate medical services for those behind bars.

The 2019 report reviewing jail operation for Shasta County said the lack of standards and requirements in the jail’s Wellpath contract is "a major vulnerability for the county." FILE PHOTO, MATT BRANNON/RECORD SEARCHLIGHT

In late 2018, Shasta County paid another consultant, CGL Companies, $97,000 to review jail operations. The consultant's review found the lack of standards and requirements in the jail’s Wellpath contract is “a major vulnerability for the county.”

Wellpath did not immediately respond to a request for comment on this article.

Randall said he plans to review the jail's medical contract. He said he wasn't personally aware of complaints of people not receiving medications. Others who have been held in the past and three attorneys voiced similar complaints to the Record Searchlight.

Complaints of inadequate health care are pervasive at many of the jails with high death rates.

Monterey County, which had one of the 10 highest death rates of jail systems reviewed by the Record Searchlight, also contracts medical services through Wellpath. Since 2018, the county has been a part of over $7 million in settlements from five wrongful death suits.

Despite that outcome, Monterey County Sheriff Steve Bernal said the jail's provider delivers "top notch" medical care, noting that the jail books many people already in poor health.

"They get the best quality health care with Wellpath, and many of them would likely have died even if they weren't in custody," he said when asked about 26 in-custody deaths since 2005.

However, using in-house providers for medical care doesn't on its own guarantee better results.

Unlike Shasta and Monterey, Tehama County uses its county health agency for medical services rather than a private contractor.

Tehama County's jail death rate is the highest out of the 53 counties reviewed. From 2005 to 2019, it reported 15 deaths out of about 57,000 total bookings. No county of its size or smaller reported more than six deaths in that timeframe. The next-largest jail system, in Tuolumne County, reported four.

A prisoner sleeps during a mid-morning visit to the Monterey County Jail in Salinas. JAY DUNN/THE SALINAS CALIFORNIAN

Grand jury reports from 2016 and 2017 stated the most commonly reported grievance is dissatisfaction with medical care, something Tehama Sheriff Dave Hencratt attributed to former state prisoners who “know how to work the system and claim mistreatment.”

When the county went forward with plans for a second jail facility, a cost analysis team in 2017 found the number of health workers at the existing jail was "not adequate for fulfilling the needs of the inmates."

"On the medical side, nursing staff are working 12-hour shifts and running non-stop all day," read the report, which was prepared by a consultant with the help of county staff

Valerie Lucero, head of the county’s health services agency, said the Tehama County Jail has a nurse on staff 12 hours a day, seven days a week and a medical assistant working eight hours a day, five days a week.

Of the 15 deaths in jail custody, the manner of death is available for 13. Eight were reported as suicides, a category of jail deaths considered "mostly preventable" by a 2017 expert panel studying mortality in corrections facilities.

A 2018 grand jury report noted that the jail had no trained mental health personnel on staff. Lucero told the Record Searchlight, while no mental health specialists work out of the jail, mental health clinicians from the county health department do rotate over at certain times, "depending on who needs to be seen.”

The jail also has a phone line available for people that want to talk to Tehama County Mental Health. However, Schwartz noted that jailers shouldn't count on those with mental health issues to always know when to reach out for help, since some might not recognize when they could use treatment.

In 2015 alone, the jail had four deaths, two of them suicides. The state’s third-largest jail system, San Bernardino County, also reported four deaths that year — except it was out of nearly 60,000 bookings that year, while Tehama County admitted fewer than 3,500 people.

What could the agency do to cut down on the number of jail deaths? “I don’t know the answer to that question," Hencratt said. "If I did, I would be a genius, I guess.”

The outside of the Tehama County Jail in Red Bluff, California. RED BLUFF DAILY NEWS

Staffing shortages lead to a lack of supervision

A lack of adequate staffing is among the most visible issues affecting county jails.

California's Board of State and Community Corrections, which inspects county jails every two years, noted in 2016 and 2018 that one of the most common failings among county jails was inadequate staffing, resulting in mandated cell safety checks being late.

Some reports play out the consequences of that a step further. In 2019, a Washington state law firm released an analysis on county jail deaths from 2005 to 2016, which found “deaths would have been avoided” had more staff been around to adequately supervise those in its care.

“Other deaths we reviewed demonstrate a lack of appropriate attention from medical or mental health care professionals, either because they were not actually present in the jail at relevant periods or because they were inattentive because of the sheer number of other demands on their time,” read the report by Columbia Legal Services.

The CGL consultant's review commissioned by Shasta County in 2018 found staffing levels "strain" to meet the workload, are insufficient and led to high rates of overtime. The report says low staffing levels “may impact safety" within the facility.

The review stated Shasta's jail had about one staff member for every four inmates, the lowest staff-to-inmate ratio among five counties the report examined with similar demographics. For comparison, Humboldt County’s ratio (0.67) was nearly triple Shasta’s (0.24).

This chart from a 2018 jail operations review shows how Shasta County has the lowest ratio of staff to inmates among four other county jail systems with similar demographics. CGL REPORT

Based on national best practices, the consultant's review stated 15 more staff members are required to provide needed coverage without undue reliance on overtime.

Randall said the facility has added one new position since the report, noting that agencies across the state have struggled with staffing.

In Tehama County, about 19% of sheriff's office positions were vacant as of mid-August, according to a letter Hencratt wrote, noting 24 out of 127 positions were unfilled.

“When we’re a full staff with corrections deputy and deputy sheriffs, everything runs pretty smoothly. When we’re not, we have to rely on overtime shifts,” Hencratt told the Record Searchlight. “I would say I’m comfortable with the number of people that are able to fill shifts, but I’m not comfortable with the amount of vacancies we have.”

The union representing deputies in the county has called the jail overcrowded and understaffed.

That could have spillover effects on supervision inside the jail. State regulators with the Board of State and Community Corrections have inspected the facility twice in the past four years, each time noting failures to perform safety checks on people at required 60-minute intervals.

Hencratt disagreed with the finding, saying the problem was due to electronic scanners jail guards use to log times when making their rounds. However, the most recent inspection stated some of the safety checks not done within the 60-minute requirement "were not related to the malfunction or the intermittent operation" of the scanners.

A lack of supervision was also brought up in a Monterey County wrongful death case that ended in a $1.6 million settlement in 2019. A medical expert said the man — a heroin user whose autopsy said withdrawal may have contributed to his 2015 death — would likely still be alive had jail staff conducted its required safety checks.

Monterey County had nine deaths in jail custody from 2017-2019, more than San Francisco County, which admitted about 13,000 more people in that timespan. JAY DUNN/THE SALINAS CALIFORNIAN

Later that year after the death, Monterey County Sheriff Steve Bernal said he transferred 24 deputy sheriffs from patrol to corrections.

"Since then, I believe our staffing is sufficient and safe," he wrote in an email.

However, at a 2019 county supervisors meeting, Bernal suggested an outside review might still recommend more workers. When county officials suggested auditing jail operations, Bernal warned the board to be careful what it wished for because a review could result in higher staffing levels, the Monterey Herald reported.

Another county in the top 10 of death rates was Fresno, with 75 deaths in jail custody from 2005 to 2019. Reporting from the Sacramento Bee showed the county jail has struggled to fill its budgeted positions, with 82 of them, or 14%, vacant in early 2018.

Can California rectify deep-seated issues in jails?

Experts say addressing problems with staffing, supervision and medical care can have a big impact on safety for both guards and the people they're guarding, as well as limiting the risk for counties that could face settlements in the millions from wrongful death suits.

That process begins with more oversight, according to Deitch. California has an oversight agency in the Board of State and Community Corrections, but Deitch noted it has been criticized for lacking teeth in enforcement. She said the oversight that exists tends to focus on jail rules and regulations as opposed to how people on the inside are being treated.

“There are very few opportunities for people in custody to express their concerns to an oversight body or get relief for any problems they’re experiencing,” Deitch said. “And it’s worth noting that, in every other western country, routine oversight and monitoring conditions of confinement is absolutely the norm. So the U.S. really stands out with its failure to provide that kind of ongoing monitoring."

//

Nick Straley, an attorney who worked on the Washington state jail deaths report, said society “hasn’t been willing to do what’s actually necessary to care for people and so we leave it to the criminal justice system and local jails.”

Straley said it’s often difficult to build public support for improving jails because they’re “the last place that anyone wants to spend any money.”

That stigma persists even as consequences of inaction lead to more deaths, some of which could have been avoided. Last year, California hit a 15-year high in the number of county jail deaths with 157, according to the state’s Department of Justice.

But more money alone can’t rectify deep-seated issues in jails.

“Everybody wants to say, ‘Oh if I just had the resources,’ but in most cases that’s just not the issue,” Schwartz said. “It’s about how well things are managed.”

In Part 3 of this series on jail deaths, the Record Searchlight looks at some strategies jails have used to improve safety and cut down on the number of deaths.

This article is the second in a three-part series. Matt Brannon wrote this story while participating in the USC Center for Health Journalism's California Fellowship. To share how county jail incarceration has affected you or a loved one, email jails.recordsearchlight@gmail.com.

[This story was originally published by RecordSearchlight.]