Part 2: EDs Deal With Shortfalls In Mental Health Care

This story was produced as part of a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Part 1: Bottleneck in Psych Care Leaves Hospitals, Patients in the Lurch

Part 3: Hospitals Try to Balance Care, Financial Constraints

An emergency department director with UC San Diego Health, Dr. Gary Vilke keeps a close eye on trends. One that leaps out: more patients in the throes of a mental health crisis.

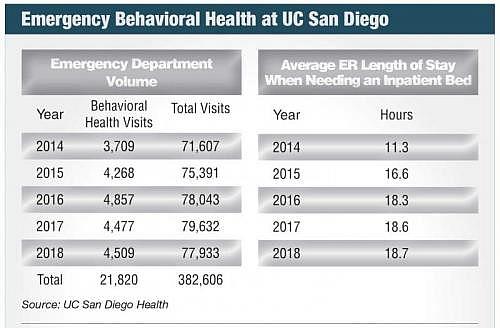

There were more than 4,500 psychiatric visits to the health system’s La Jolla and Hillcrest emergency rooms last year, 22 percent higher than in 2014. Other San Diego hospitals — Palomar Health, Sharp HealthCare and Scripps Health — reported increases, though shared limited data.

The rise in patients has left hospitals searching for solutions, with an eye toward the bottom line. It’s costly to care for patients languishing in emergency departments, running up losses in behavioral health, hospitals say.

And the federal government took steps to tie hospital payments to how long psychiatric patients stay in the emergency rooms.

“It’s not a sexy topic. It’s not a moneymaking topic. But it’s an area we really have to look into as a community,” said Vilke.

Longer Waits

Amid psychiatric emergencies increasing, the number of inpatient and continuing care beds declined, according to data, a major factor in longer waits, hospitals say.

At UC San Diego last year, psychiatric patients in need of an inpatient bed spent 18.7 hours in the emergency department on average, up seven hours from 2014.

For Sharp HealthCare, the region’s largest private provider of behavioral health services, waits averaged 21 hours in 2017, the only year for which data was available.

The term for this: “ER boarding,” lengthy cases of which can lead to poorer patient outcomes, according to physicians, while financial ramifications loom.

In 2017, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services required that hospitals report new data on how long psychiatric patients spend in the emergency room. The move paves the way for CMS to use reimbursement rates to reward or punish hospital performance, according to consulting firm Vituity.

The Caseload

While emergency psychiatric visits rose 22 percent from 2014 to 2018 at UC San Diego, overall emergency volumes increased 9 percent in the span.

Vilke said UC San Diego added case management and social workers to coordinate outpatient resources, in a bid to curb readmissions. It also launched several programs, one of which offers outpatient services to divert less-intensive cases away from emergency rooms.

San Diego County experienced 31,448 mental health visits to emergency rooms in 2017, according to California’s Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

Most emergency rooms are equipped for physical ailments. But hospitals are rethinking the model.

Palomar Health steers some mental health emergencies toward a crisis stabilization unit, in hopes of avoiding needless inpatient stays. Designed as an alternative to crowded emergency rooms, the relaxed environment allows patients to stay for up to 24 hours under the watch of specially trained social workers, nurses and psychiatrists. They’re then shepherded toward follow-up care.

Like a traditional emergency room, patients well enough to go home are discharged, while some are admitted to an inpatient facility.

Palomar Health CEO Diane Hansen said the unit, combined with Palomar beefing up outpatient services, lessened pressure on the system’s emergency departments and inpatient ward.

“People will come to our ED and they don’t necessarily need to be in an ED. They are in a crisis and they just a need an environment where they can be assessed, treated and de-escalate,” she said.

De-escalation Pays Off

The eight-recliner unit operates on a site which was recently sold, but a new stabilization facility with 16 recliners will open this summer, adjacent to the emergency room at Palomar Medical Center Escondido.

Dr. Scott Zeller pioneered the first such unit decades ago while heading psychiatric emergency services at a hospital in Alameda County. Now, as the vice president of acute psychiatry at the company Vituity, he advises hospitals intrigued by the concept.

One of the dozens of hospital that embraced the concept recouped $1 million in boarding costs within nine months, according to a Vituity report. But deficient hospital reimbursement can be a barrier.

The same could be said of reimbursement for other early-intervention strategies, like telepsychiatry, in which experts diagnose via video. Zeller has pushed for greater payment through his other role: chair of the National Coalition on Psychiatric Emergencies.

“The wheels of changing reimbursements and how these are done nationally and even in the statehouses are very slow,” he said.

Psychiatric Beds

Dr. Paul Summergrad sees crisis stabilization units as one solution, not a panacea. He’s a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, and psychiatrist-in-chief at Tufts Medical Center.

“When you get backup in emergency rooms, it’s because inpatient bed availability isn’t there,” Summergrad said. “People want to believe you can get away without having inpatient psychiatric beds, but it’s just not true.”

San Diego County had about 700 inpatient beds in 2017, a 30 percent drop from a peak two decades ago, according to data from the California Hospital Association. A drop-off occurred in Los Angeles, Riverside and Orange County as well, on account of beds operating at a loss, hospital officials say.

San Diego has 21 beds per 100,000 people. The goal is 50 beds, according to the association.

Hospital, Company Partnership

In part to ease emergency department waits, Scripps Health recently announced a partnership to build a facility with 120 inpatient psychiatric beds, about tripling the number of patients it can treat. It’s set to open in 2023.

Scripps partnered with Acadia Healthcare, which provides behavioral health services in 40 states, the United Kingdom and Puerto Rico. Acadia would cover 80 percent of the project cost while Scripps would pick up the rest, a model not seen elsewhere in San Diego.

Beyond beds, the hospital system boosted de-escalation training in recent years, given that some mental health patients in emergency rooms can be disruptive — or present a safety risk to staff or other patients.

And the hospital system grew its psychiatric liaison team, which makes the rounds in its emergency departments for quicker evaluation and triage, according to Dr. Jerry Gold, administrator of Scripps Behavioral Health Clinical Care Line.

Some hospital officials point downstream.

Long patient delays for continuing care, like a skilled nursing facility, tie up inpatient beds, fueling emergency department waits. So said Dr. Michael Plopper, chief medical officer of Sharp HealthCare.

The first part of this San Diego Business Journal series focused on the back-end bottleneck, which contributes to financial struggles in behavioral health, and delays patients in a critical leg of their journey.

Across the nation, sweeping changes that deinstitutionalized psychiatric patients starting in the 1960s weren’t followed by a corresponding increase in treatment units and supportive housing. That’s on account of low mental health reimbursement and funding, particularly compared with, say, cancer or heart issues.

And while the Affordable Care Act expanded insurance coverage, lingering stigma around mental health means many patients don’t get help unless in emergency.

In San Diego, psychiatric patients in emergency care can wait up to 36 hours for an inpatient bed, based on patient interviews in 2017, according to a September report from the Hospital Association of San Diego & Imperial Counties.

For patients in such a vulnerable state, waiting can be harrowing.

Julie Benn, who was admitted to a San Diego inpatient unit in 2003 after experiencing suicidal thoughts, estimates she was in limbo for two to three hours. Every hour her anxiety rose. Part of the time she was freezing in a paper gown with little contact.

“It added so much to my anxiety,” she said. “All these thoughts raced through my head, ‘Have I done the wrong thing? I just want to get out of here. I’m totally scared to death. I’ve never done this before.’”’

In the years before, Benn said she pushed down troubling thoughts, including about a family member’s brain tumor and past mental health issues. She shared her story to help remove the stigma around mental health.

Now she’s a communications specialist at The National Alliance on Mental Illness in San Diego. Its programs include Friends in the Lobby, which through trained staff at hospitals presents potential resources to family of those undergoing a crisis.

Tri-City Considers Role

Last year, the fragility of the region’s emergency mental health system became apparent, after Tri-City Medical Center suspended its inpatient and crisis stabilization units.

In the aftermath, Palomar has seen greater numbers of “5150s,” law enforcement’s code for a person deemed a threat to themselves or others and who can be involuntarily held for up to 72 hours. It receives about 18 of these patients a day, double that of six months ago.

Tri-City continues to operate outpatient mental health services and a tele-mental health service, and could resume crisis services.

“One such partnership being discussed is the potential for Tri-City Medical Center to partner with a private outpatient mental health provider and the county of San Diego to provide crisis stabilization services in coastal North County,” the health system said in response to a Business Journal interview request.

Over the last decade, the county significantly increased the number of psychiatric emergency response teams, or PERT. They pair health clinicians with law enforcement officers, now with 72 teams.

Last year, PERT teams logged 9,714 crisis intervention contacts, a 316 percent increase from four years prior.

[This story was originally published by the San Diego Business Journal.]