Part One (English): How the COVID-19 pandemic magnified challenges for Arizona students not proficient in English

Daniel Gonzalez reported this story as a participant in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 Data Fellowship.

Other stories by Daniel Gonzalez include:

Enrollment dropped. Absences soared. How one Arizona school is fighting pandemic learning loss

How the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted college plans for Latino students in Arizona

Fernanda Davila works on a spelling packet at the kitchen table in her Phoenix home on March 8, 2022.

MONICA D. SPENCER/THE REPUBLIC

Fernanda Davila speaks only Spanish at home. The 8-year-old elementary school student lives with her parents, immigrants from Mexico, and her two younger siblings.

But at school, Fernanda's classes are taught only in English under a law passed by voters in 2000. Because of the language gap, Fernanda already struggled to understand teachers, especially when learning math. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, learning via a computer made it even harder.

All students in Arizona faced challenges when schools closed during the pandemic. Learning switched from the classroom to online instruction via Zoom for more than a year from March 2020 until spring 2021.

Standardized test data reviewed by The Arizona Republic shows that students in English language learner programs, like Fernanda, fared the worst during the pandemic.

A main reason is that students who didn't speak English faced additional challenges learning remotely because of language barriers, experts say. Long-standing inequities also played a role, they say.

"The pandemic had a really significant impact on English language learners, and I don't think it's talked about enough," said Erin Hart, senior vice president and chief of policy at Education Forward Arizona. The nonprofit seeks to improve Arizona education through programs and advocacy.

The challenges students faced when schools closed during the pandemic were magnified for students such as Fernanda whose first language is not English. English learners in Arizona are a large and growing group.

When learning suddenly switched from the classroom to remote learning via Zoom on computers, students such as Fernanda missed out on body language and other nonverbal cues, she said.

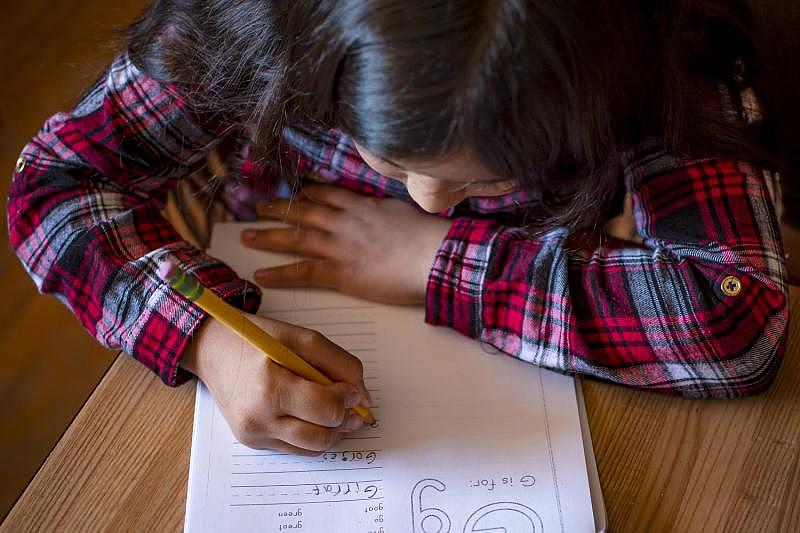

Fernanda Davila, 8, pauses to think as she completes homework in her Phoenix home on March 8, 2022. MONICA D. SPENCER/THE REPUBLIC

"Students had to grapple with their ability to be digitally literate, so that was a barrier for a lot of families. Imagine having to do that on top of not understanding English fully," Hart said.

What's more, parents of ELL students were often unable to help students with their schoolwork because they also didn't speak English. Parents who don't speak English had trouble communicating with teachers, creating even more barriers, Hart said.

"I think families were all in a different place, but I think especially for ELL students these issues are just magnified so much more, and the hurdles were so much bigger than other families had to face," Hart said.

The data shows that students in English language learning programs in Arizona had the lowest passing rates of any group, including students classified as homeless students, and special needs.

Fewer than 2% of ELL students who took the standardized math and reading tests during the 2020-21 school year passed the exams. It’s important to note that ELL students were not required to take the tests during the pandemic, so a large number did not. That makes it difficult to compare to previous years.

Data visualization by Malea Martin. Data courtesy ACLU and Population Reference Bureau.

In comparison, about 38% of all students passed the reading test and 31% passed the math test.

Those scores were down from 2018-2019, the last full school year not affected by the pandemic. That year, the passing rate for all students was 42% for both the standardized reading and math tests, data shows.

The data shows how the pandemic hurt academic performance for all students but above all students who are still learning English, experts say. The data shows how the pandemic exacerbated academic achievement gaps for students still learning English that existed long before the pandemic.

English learners for years have scored the lowest on standardized tests compared with other groups, data shows.

They also have some of the lowest high school graduation rates. In 2020, the high school graduation rate for English language learners was 56%, compared with 78% of all students, according to Arizona Department of Education data.

The decline in standardized test scores among English learners during the pandemic mirrors declines at the national level, said Melissa Lazarin, senior adviser for K-12 policy at the Migration Policy Institute's National Center on Immigrant Integration Policy.

It is particularly alarming because passing rates on standardized tests for English language learners were already so low, she said.

"Even prior to COVID, performance among English learners (in Arizona and nationally) was really at the bottom, often in the single or teen digits of proficiency. And so the fact that there is more of a decline should raise alarms because this is a population that was already well below the average," Lazarin said.

The fact that there is more of a decline should raise alarms because this is a population that was already well below the average.

Melissa Lazarin, senior adviser at the Migration Policy Institute's National Center on Immigrant Integration Policy

During his State of the State address, Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey blamed mask requirements and other COVID-19 safety measures implemented in schools for disproportionally hurting the academic performance of students of color and students from low-income families

"There's been too much attention put on masks and not nearly enough placed on math, a focus on restrictions rather than reading and writing," Ducey said. "And it's students of color and those of poverty who have been most impacted by the COVID-era posturing and politics of some school board bureaucrats."

But Lazarin said Ducey's blame is misplaced. The blame falls on educational and other inequities that existed before and were made worse after the pandemic, she said.

"Students of color and English learners have largely endured disparate impacts due to the pandemic and due to remote learning but much of the challenges were there even before the pandemic," Lazarin said. "So it's not so much an issue of masks and health and safety precautions as much as it is in general these populations of students have had less access to effective teaching, less access to equitable resources. ... We should be able to walk and chew gum at the same time."

Eight-year-old Fernanda Davila holds her puppy, Dolores, outside her Phoenix home on March 8, 2022. MONICA D. SPENCER/THE REPUBLIC

Fernanda's story

Fernanda is one of more than 91,000 students in Arizona classified as English learners, according to state Department of Education data.

Her mom, Anarely Jimenez, 28, is a stay-at-home mom. Her dad, Gerardo Davila, 28, works at an auto body shop. At the start of the pandemic, the shop closed for six months. Gerardo was laid off. After two months without work, he managed to land a job at another auto shop, she said.

Both parents are from the Mexican state of Chihuahua and mostly speak Spanish. The family lives in a two-bedroom trailer home on a large dirt lot in a predominantly working class Latino neighborhood in south Phoenix.

At home, Fernanda speaks mostly Spanish with her parents and two younger siblings, Ariel, 4, and Brandon, 3.

Spanish is the top language spoken by the vast majority of English language learners in Arizona, according to the Migration Policy Institute. A small percentage of English language learners speak Arabic, Vietnamese, Navajo and Somali.

When the pandemic hit in spring 2020, Fernanda was a first grader at Cesar Chavez Leadership Academy, an elementary school in the Roosevelt School District. About 96% of the school's 423 students are Latino, and 98% are from low-income families, according to the latest Arizona Department of Education data.

Fernanda's classes suddenly switched from in-person to online as schools across Arizona closed to help control the spread of COVID-19.

Her school provided students with iPads to use.

But at times Fernanda had trouble staying connected to the internet while in class via Zoom.

"It was glitchy," Fernanda said in English. She has long dark hair and was wearing a pink dress with black boots. She was sitting at a counter in the kitchen where she usually does her school work. During the interview, her brother kept turning on the TV to watch cartoons at full volume. Her mother kept turning the volume down with the remote.

Fernanda said it was similarly hard to concentrate during the pandemic when she was learning remotely. Her sister and brother played inside the small trailer or watched TV, she said. Sometimes her mother had to threaten to ground them to get them to quiet down.

"I couldn't pay attention," Fernanda said.

Fernanda Davila, 8, jumps on a trampoline with her siblings, Brandon, 3, and Ariel, 4, outside their Phoenix home on March 8, 2022. MONICA D. SPENCER/THE REPUBLIC

On top of that, Fernanda couldn't always understand what her teacher was saying in English.

Up until then, Fernanda had decent grades in all of her subjects. She mostly received 2s and 3s out of 5 on all of her subjects.

"But she started having trouble with mathematics," her mother Anarely Jimenez said. "It confused her the most."

Jimenez remembers telling Fernanda that if she didn't understand something to make sure she asked her teacher to explain it again.

Jimenez said she tried to help her daughter with her homework, but she often couldn't because she doesn't speak English very well.

For example, Fernanda recently took out a worksheet instructing students to write down words that begin with the letter F. One of the words Fernanda wrote down was the word "four." Fernanda had to explain to her mother that the word "four" was not the same as the word "for."

"They sound alike but have different meanings," Jimenez said.

Fernanda Davila, 8, works on homework as her mother, Anarely Jimenez, looks over her progress in their Phoenix home on March 8, 2022. MONICA D. SPENCER/THE REPUBLIC

Jimenez said her lack of English made it difficult to communicate with Fernanda's first grade teacher. Sometimes she enlisted the Spanish-speaking nurse or other Spanish speakers at the school to translate.

Things got better in second grade, Jimenez said. Fernanda's classes remained remote for most of the year, but her second-grade teacher spoke both English and Spanish.

"When she was in first grade, her teacher spoke only English. But her teacher in second grade spoke both languages so there was much better communication because her teacher could help me (in Spanish) when I had any questions," Jimenez said.

At the start of third grade, Jimenez received a letter from the Arizona Department of Education. The letter, which she shared, informed her that Fernanda had tested out of the state's Arizona English language learner assessment program, known as AZELLA.

Jimenez was relieved. She said she believes that while the English only program helped Fernanda learn English, it kept her behind academically and socially by pulling her out of her regular instruction for several hours a day.

Jimenez shared some of Fernanda's third-grade test results. The results showed that Fernanda scored 942 out of a possible 1,400 on the English language arts assessment test, and 893 out of 1,400 on the math assessment test. The scores showed she was below target levels in both subjects and considered partially proficient in English and minimally proficient in math.

Eight-year-old Fernanda Davila works on a spelling packet at the kitchen table in her Phoenix home on March 8, 2022. MONICA D. SPENCER/THE REPUBLIC

Advocates: It's time to revisit Arizona's 'English-only' law

Some experts and advocates say the pandemic showed how it's time to rethink the state's more than 20-year-old English-only law, which they believe is rooted more in politics than effectively teaching English language learners.

"It speaks to a system that is set up for them not to be successful," said Stephanie Parra, executive director of Arizona Latino Leaders In Education, a Phoenix-based nonprofit group that advocates for Latino students.

"These challenges were not just spurred on us," Parra added. "We have created the conditions of a very inequitable system where some communities have access to the resources, supports and systems that they need to be successful, while a lot of communities do not. And whether it's by design or unintentional, it is reality."

Voters passed Proposition 203 in 2000, a time of political turmoil fueled by an influx of Spanish-speaking immigrants from Mexico and Latin America to Arizona.

The so-called English-only law barred students from receiving instruction in their own language while in the process of becoming proficient in English. Under the law, students were required to spend four hours a day immersed in English-only instruction. In 2019, the state Legislature lowered the amount of English-only instruction from four to two hours a day.

Bills that would allow voters to decide if Proposition 203 should be repealed have stalled in the Arizona Legislature in recent years.

When Proposition 203 was passed, proponents touted the law as a way for students to quickly learn English. Parra and others view the law as an attack on Latinos maintaining their culture and language.

She said she believes more resources are needed to help English language learners make up the academic ground lost during the pandemic.

The state also needs to adopt a system that views bilingualism as an asset, not a deficit, she said.

The English-only law sends a message that "it is not a value to have a community that is bicultural and bilingual, or multilingual," Parra said.

She said she believes the state needs to embrace English language learners as "an asset" and "invests in them in that way so that they aren't just catching up because they have a lot of catching up to do, but that they're fully thriving in the system," Parra said.

Critics of Proposition 203 say the law doesn't support English language learners. Rather it hinders them academically. THOMAS HAWTHORNE/THE REPUBLIC

English learners going back years consistently have scored in the single digits on state standardized tests among all groups, putting them at the lowest rungs of all students, including students with special needs, according to a report released in January by ALL in Education.

But it is difficult to tell from standardized test scores alone why English learners are scoring so low on math and reading tests. It's unclear if they haven't learned the content, or whether their limited English prevents them from understanding the questions.

"Was the barrier that they didn't understand the content or was the barrier that they did not understand English?" said David Garcia, an associate professor of education at Arizona State University and director of the university's Arizona Education Policy Initiative.

Nevertheless, Garcia said standardized test score data should provide a map of where the state should be investing resources to help students who fell behind during the pandemic.

The most resources should go to the students who scored the worst, "and in this case (those resources should be put) into English language learners," Garcia said.

He recommends the state Legislature retool the state's formula for allocating tax dollars to give more weight to school districts with high numbers of English language learners.

Garcia blamed Arizona's English-only law for doing a poor job of educating students not yet proficient in English. By pulling them out of class for several hours a day for English only immersion, the students tend to fall behind in other academic subjects such as math and reading, Garcia said.

"Right now, the primary focus for English language learners is to learn English. That has been the focus of the policy, " Garcia said. "But part of the challenge with that is with too much focus on learning English, students start to fall behind academically."

The question is was the barrier that they didn't understand the content or was the barrier that they did not understand English?

David Garcia, director of ASU's Arizona Education Policy Initiative

He would like to see school districts given more autonomy to create English language learner programs tailored to the needs of their students.

The focus, he said, should be on teaching English language learners in more than one language until they become proficient in English. That way they would be learning English without falling behind academically, he said.

"That means that if a student is taking intensive English courses for the purposes of learning English, that's great. But if they needed to have part of their instruction in math in Spanish so that they can understand math, then that would make a lot of sense to me," Garcia said.

That sort of approach toward English language learners would help them preserve their home language, Garcia said.

"We have the ability in the state to have a (bilingual) workforce that can communicate in English but can also communicate ... out there in another language," Garcia said. "There are so many parents who would love to have their students be able to learn another language. And yet we have the ability for the English language learners who already have a base in Spanish to do just that."

Daniel Gonzalez reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 Data Fellowship, which provided training, mentoring, and funding to support this project.

Reach the reporter at daniel.gonzalez@arizonarepublic.com or at 602-444-8312. Follow him on Twitter @azdangonzalez.

[This article was originally published by AZCentral.]