Part Three: The opioid epidemic is putting immense pressure on Maine’s child welfare and education systems

This story was produced as part of a larger project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2021 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this project include:

‘Lucky to be alive right now’: Rumford man credits doctors, awareness, luck for avoiding addiction

At the root of an epidemic in Maine: a prescription pad

A work injury and a prescription. One Maine woman’s story of the cycle of addiction

Methodology: Where the child welfare and education data came from

Tiana Warriner looks at a comic strip her daughter, Sophia, 9, drew, featuring their two new kittens as action heroes as her son, Jayce, 7, listens in. Warriner says her kids have really noticed a difference since she has gotten sober. “My kids tell me sometimes I need a meeting. Warriner said, “They tell me all the time, you’re not afraid anymore. They’re not worried. They’re not scared. They like their mom.”

Andree Kehn/Sun Journal

Until she met someone in recovery last year, Tiana Warriner said she didn’t even know what sobriety was “or that recovery was an option.”

Warriner said she had a tough childhood.

Her parents grew up poor in Rumford but worked hard to get good jobs and nice houses, eventually moving from the Lewiston-Auburn area to a lake house in Turner.

“The bills were always paid and the lights were always on,” she said, but things were not always easy.

“My parents did the best they could with what they knew. They were very religious. They worked really good middle-class jobs,” she said.

Warriner, now 28, and her friends started going through their parents’ medicine cabinets when she was just 13 years old. She would progress to harder and harder drugs, like cocaine, before she was old enough to legally drink; she said she didn’t know how to get help.

“I really just thought it was like you pull yourself up by your bootstraps. You get over it, you suffer,” Warriner said. “And you make it look really nice on the outside, and that’ll be fine.”

That was until last year, when Warriner started a new job at a local furniture refurbishing business. One of her co-workers, the owner’s daughter, was in recovery herself and could see that Warriner was in distress.

Warriner said that at the time, she felt that she “finally had hit rock bottom.”

“I was miserable. I had everything I thought I wanted to (have). I had the job I wanted, the car, the house, my kids. I was like, single and miserable. I hated waking up every day. I hated life.”

A few weeks after Warriner started working at the shop, her co-worker approached her and asked if she had ever considered going to a meeting.

“At that point, I was just so desperate I’m like, ‘yeah.’”

Warriner showed up drunk to her first meeting at Recovery Connections of Maine in Lewiston.

“I drank before I went because I didn’t know what I was doing,” she said. She remembers showing up and meeting people who were all smiling at her. Her first reaction was that it was overwhelming and “a little culty.”

“I have no idea who spoke. I have no idea what they talked about. I just remember like, for the first time I felt happy and excited.”

She was still wary of everyone, however.

“I thought it was all fake.”

But she liked her co-worker who brought her there, who took her under her wing, so she went back for another meeting. After three weeks, she picked up her first sobriety chip, a reward for staying sober.

“And I haven’t looked back,” Warriner said.

‘IT’S ABOUT TRAUMA’

Gordon Smith, who was appointed by Gov. Janet Mills to serve as the state director of Opioid Response in 2019, said that he no longer accepts the premise that the opioid crisis in Maine was singularly “occasioned by, you know, poor prescribing and people getting hooked on pharmaceutical-grade opioids.”

For years, Smith served as the executive vice president of the Maine Medical Association. In 2015, he served on the Maine Opiate Collaborative along with then-Attorney General Mills, and in 2016 contributed to the public information campaign to teach doctors how to safely taper their patients.

“A number of people did (develop substance use disorder via a prescription) and I don’t want to excuse that entirely. But I do think that each person’s use is really complicated and I suspect that a lot of people, if they hadn’t gotten that script or had that sports injury, may well (have) acquired a substance disorder somewhere else along the way,” he said.

It is impossible to say if and how the opioid crisis would have unfolded differently in Maine had there not been such a proliferation of prescription drugs. For Smith, however, it’s less important to speculate how things might have been different had drug manufacturers like Purdue Pharma not aggressively marketed their highly addictive drugs than it is to focus on how the state can respond now.

In addition to harm reduction and treatment, Smith said his office is also focused on addressing the underlying environmental factors that can increase an individual’s predisposition for developing a substance use disorder.

“It’s about trauma,” he said.

There are a number of factors that can cause a person’s dependence on a drug to transform into an addiction.

Genetics. Childhood trauma. Bad luck.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse, the federal agency within the National Institutes of Health, cites multiple peer-reviewed studies with robust bodies of evidence that suggest more than half of a person’s predisposition to addiction may be genetic.

Dr. Paul Vinsel, an addiction medicine physician at Tri-County Mental Health Services and Central Maine Medical Center in Lewiston, said that researchers are finding that different genes can affect the way the body “perceives the drug and the way you metabolize the drugs, and different genes put you at higher risk for developing addiction, no matter what your environment is,” just like certain genes put some individuals at higher risk for type 1 diabetes or different types of cancer.

But environmental factors, especially childhood experiences, may also play a large role in explaining why some people are more likely to develop a substance use disorder over others.

Dylan McKenney, seen March 18, is chief child psychiatrist at St. Mary’s Regional Medical Center in Lewiston. Andree Kehn/Sun Journal

Dr. Dylan McKenney, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and the associate medical director for pediatric behavioral services at St. Mary’s Regional Medical Center in Lewiston, said that connecting life experiences to disease risk is a “tricky business because it’s always unclear whether the thing that you’re tracking is just correlated or whether there’s causation involved.”

In other words, a person’s environment cannot predict the risk of developing substance use disorder in the same way that, for example, gene testing can predict a person’s increased risk for developing certain kinds of cancer.

But a tool that came out of a landmark study conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente in the 1990s offered what McKenney described as not so much a diagnostic tool for children but “more of a universal risk factor for disease,” that should be treated as informative and as guidance.

The resulting paper, “Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults,” showed a strong correlation between what it dubbed “Adverse Childhood Experiences,” or ACES, and a higher prevalence of disease among adults.

“It kind of revolutionized understanding of (the) social causes of disease,” McKenney said.

An adult’s ACES score is evaluated on a scale, which assigns one point for each type of experience, regardless of the magnitude of the experience. For example, a point for a parent or caregiver with substance use disorder, a point for parents’ divorce and a point for experiencing physical abuse.

The idea of ACES, McKenney said, is “if you have all those things going on in your childhood then, you know, we sort of expect that we’re talking about like, sort of a chronically stressed childhood without the positive, supportive factors that help one learn to cope in a healthy way, or to have a sense of hopefulness about the future, or a sense of positive self-esteem or even a kind of more solid personal identity.”

SCHOOLS AT THE FRONT LINE

When OxyContin manufacturer Purdue Pharma filed for bankruptcy in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, 64 public school districts from across the country — almost half of which were from Maine — filed an objection to Purdue’s proposed reorganization plan on behalf of schools nationwide.

The suit, filed last April, claims that providing services to children born with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, which is when infants are exposed to substances in utero that often leaves them with long-term developmental disabilities requiring special education services, have cost American schools more than $127 billion.

The 30 Maine districts that joined the suit represent nearly 56,000 students across the state, according to enrollment data from the National Center for Educational Statistics.

“It’s pretty indisputable that the effects of opioid use do create additional costs in the special education realm because students have higher behavioral issues, higher learning issues and therefore require additional special education services,” said Melissa Hewey, an attorney with Drummond Woodsum in Portland who represented the Maine districts in the suit.

Special education services statewide for the 2020-21 school year cost nearly 60% more per pupil than for the 2009-10 school year, which was double the rate that per-pupil costs rose for regular instruction and overall expenditures during the same time period, according to financial data from the Maine Department of Education.

“The opioid crisis has certainly touched schools,” Lewiston Public Schools Superintendent Jake Langlais said. “I don’t know that we’re able to quantify that in full right now, you know, the overall impact on things, but I think that certainly there’s been an effect.”

In addition to students who may need additional services due to prenatal substance exposure, Langlais said he’s observed a growing number of students who struggle both behaviorally and academically since he first became an administrator with the district in 2014. And the COVID-19 pandemic has only worsened the situation.

“We have students walk in the school and it just seemed like they didn’t know what was happening. And they just couldn’t make sense of things because their mind was so filled with whatever happened outside of school,” he said.

“And then they feel behind. They worry about their family members — are they going to live? That trauma is not exclusionary of family and bloodline and love and so it really, it lands us to a place where we have more kids that access counseling,” which in turn can disrupt the student’s schedule further since there are a limited number of counselors.

The district’s per pupil expenditures for special education more than doubled from 2010 to 2021. During the 2020-21 school year, Lewiston spent $4,138 per student to provide special education, a nearly 90% increase compared to the 2009-10 school year.

The cost to provide regular instruction rose 52% during the same time period. There were 5,184 students enrolled in Lewiston public schools last year.

Langlais said he’s also observed an uptick in the number of reports the district makes to DHHS.

Annual child protective services reports dating back to 2003 show that, besides law enforcement, the majority of reports of a child’s possible abuse or neglect made to the Office of Child and Family Services are from school personnel.

Even when there is no abuse or neglect, a parent or caregiver’s substance use can still impact children in other ways.

“But the instability that addiction creates in a household is massive,” Langlais said. “I mean, it’s just a really challenging component. Substance (use) if students can see it, you know, the long-term effect of things that we can’t see is how, you know, this kind of disease of addiction is often passed down from generation to generation.”

A STRESSED SYSTEM

Since 2013, a parent’s or caregiver’s substance use has been identified as a risk factor in about half of the instances when a child was removed from the home. That is well above the national average of 39% in 2019.

Maine’s rate of substance use as a risk factor for removal — which includes both drug and alcohol use, though annual Office of Child and Family Services reports on child protective services in Maine indicate that drug use as a risk factor is more common than alcohol use — has been on a steady rise since 2000 and consistently above the national rate.

In 2000, substance use was a risk factor in 35% — slightly more than a third — of cases in Maine, compared to one-fifth of cases nationally. The national rate did not hit 35% until 2016. By then, Maine’s rate had been at or above 50% for three consecutive years and where it has remained since.

“The impact of substance use and, in particular, the opioid epidemic on children and families, has been significant,” reads the Maine Department of Health and Human Services’ 2021 annual Child Protective Services report.

“Beyond removal, when substance use is a factor in a case, it takes on average an additional three months for children to reunify with their parents when compared to those cases that do not involve substance use,” said the report.

The opioid epidemic in Maine is putting additional pressure on an already incredibly stressed child welfare system.

Investigations conducted by Casey Family Programs, a national firm DHHS hired following a rash of child fatalities in a single month last year, and by the Office of Program Evaluation and Government Accountability, as well as reports by a several independent oversight panels including the Maine Child Welfare Ombudsman, pointed to many of the same issues within the department.

Namely, they found that a chronically understaffed Office of Child and Family Services faced intense workloads, a rigid bureaucratic system that negatively impacted their ability to complete thorough investigations, high turnover and poor communication and inadequate training that often threw inexperienced caseworkers into tough situations without much support.

“Staffing shortages, staff burnout and other challenges are only made worse by the ongoing pandemic,” Jeff McCabe, the director of politics and legislation for the Maine Service Employees Association, the union representing child protective services workers, told lawmakers earlier this year.

In a MSEA survey of caseworkers and supervisors conducted last September, more than two-thirds of respondents said that their caseload is so intense that they are “afraid a child is put in danger,” or it is “beyond human capabilities.”

Only two out of 77 respondents said caseloads were manageable.

More than half said they contemplated resigning at least once a week.

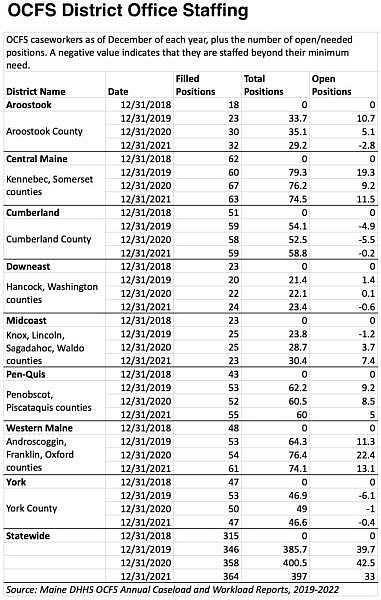

OCFS caseworkers as of December of each year, plus the number of open/needed positions. A negative value indicates that they are staffed beyond their minimum need. Source: Maine DHHS OCFS Annual Caseload and Workload Reports, 2019-2022

AN ILL-PREPARED SYSTEM

The first few years of Warriner’s children’s lives were filled with some of her heaviest drug use. She and her children’s father were both struggling with substance use disorder, made worse by the death of her best friend, whom she called her older brother because his family took her in when she left her own house as a teenager.

Warriner said after her friend died, there were “four months I don’t remember at all.”

“I wasn’t living anywhere,” she said. “The hardest day of my life was dropping my kids off at my ex’s parents’ house and telling them I can’t take care of them.”

Office of Child and Family Services took custody of her children for about a year. Warriner called the entire experience dealing with the department “horrifying.”

Tiana Warriner listens to her son Jayce, 7, explain why he would like to have a data plan on his phone. Warriner has chosen to live without an internet connection at home. She does not want to deprive her kids of anything, but they enjoy playing as a family without it. They recently upgraded from a VCR to a DVD player. Warriner prefers the simplicity. Andree Kehn/Sun Journal

“I just felt like they didn’t understand and if they could only understand, they could only see how much I love my kids,” she said. Warriner said throughout the process, which included family and drug court, they never directed her to recovery resources.

“They really just tested me” for drugs, she said. She saw a counselor, but they were “brand new” and Warriner felt they didn’t really know what they were doing.

She also thought that the Office of Child and Family Services only cared that her situation looked good on the outside. And the office wasn’t concerned that she was actually receiving treatment for her substance use disorder, Warriner said.

Mostly, she didn’t know what they expected of her. Her caseworker changed four times and her court-appointed lawyer changed three times.

“And the court case was horrifying. One of their biggest arguments against me was the fact that I didn’t have a community or any help. And it was humiliating.”

At the first family team meeting with the Office of Child and Family Services, she says they told her, “Well, you’re going to get a place to live and figure out your life if you want your kids back. Have fun,” Warriner said.

She had no idea how to do that, she said. And of course she didn’t have a community. Community is the opposite of addiction, she said.

The entire process “didn’t teach me how to be a mom,” she said. “It didn’t show me what I had been doing wrong. Just that the drugs were the problem, stop the drugs and you can have your children.”

Lack of parental support was repeatedly recognized in the various investigations into the Office of Child and Family Services.

“Another challenge we heard was that parents may not recognize child safety risks and concerns raised by Child Protective Services as problems because it is what they have known and experienced in their families as both children and adults,” according to the Office of Program Evaluation and Government Accountability’s findings, which were released in March.

“Many families do not have much for natural supports around them, and may not be aware of the professional services available to them.”

Warriner, now about a year into her recovery, seems to be doing well. After going to that first meeting at Recovery Connections of Maine in Lewiston, she began volunteering. Last November, she was hired to serve as executive director for RCOM’s sister organization, the R.E.S.T. Center, a recovery assistance and community center in downtown Lewiston.

After many months of being chronically unhoused, last summer she repurposed a camper. She put a positive spin on it for her kids, now 7 and 9, by telling them to think of it like a summer camping trip.

Warriner and her kids, whom she shares custody of with her ex, are now settled into an apartment. She’s finally out of the “cycle of chaos” that she said she was stuck in for half of her life.

And her kids have noticed.

“My kids tell me sometimes I need a meeting. So they absolutely see the difference,” Warriner said.

“They tell me all the time, they’re like, not afraid anymore. They’re not worried. They’re not scared. They like their new mom. They’re just happier all around,” she said.

“And we have honest and open communication because I can be present and follow through and be honest. And I’m not afraid all the time anymore and doing everything out of fear. That has made a big difference in their (lives) because they’re less afraid.”

The project was produced in partnership with the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism through its 2021 Data Fellowship program.

This story has been updated to include additional context regarding a quote from Gordon Smith on opioid pain medications.

[This article was originally published by Sun Journal.]