Part Two: Over Six Years, There Have Been More Than 30 Suicides at Camp Pendleton

This story was completed as a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2021 Data Fellowship.

Other stories include:

Part One: Young Men in Military Almost Twice as Likely to Die By Suicide as Civilian Peers

Part Three: Women In Military More Than Twice as Likely to Die By Suicide as Civilians

Illustration by Carolyn Ramos for Voice of San Diego

Voice Of San Diego

From the time he was five years old, Alex Jones dreamed of joining the Marine Corps. But dreams, sometimes, are woven with dark threads the dreamer cannot see.

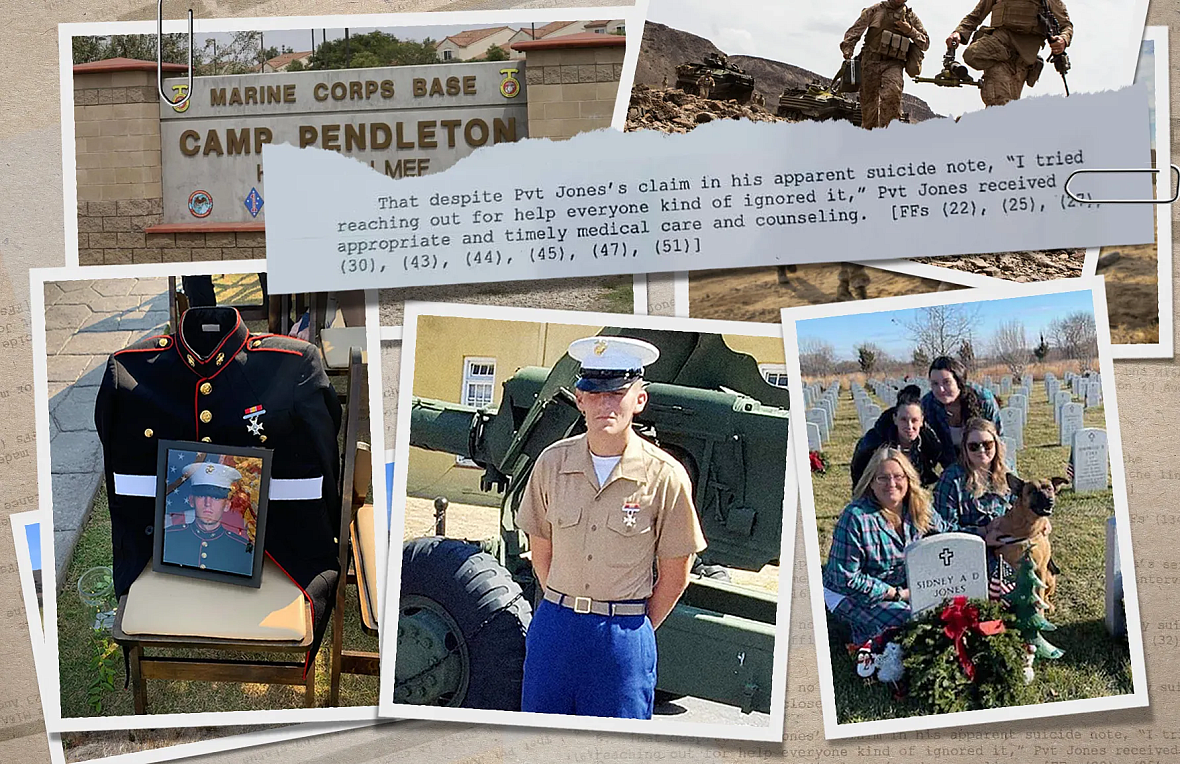

The day he graduated from boot camp, he told his mother and sisters, was the happiest of his life. He went home on a brief leave and then to Camp Pendleton to finish his training. The base is 125,000 acres of scrubland, dominated by dry, rocky hills. Its western boundary is the Pacific Ocean. Jones needed to complete a 29-day combat training that would keep him in the wilderness for days at time, using live ammo and learning the skills of war.

But before the training could begin, a single incident threw Jones off his path. He injured his back on a 10-kilometer hike. Diagnosis: acute back pain along the sciatic nerve. He had harder and longer hikes in front of him. Since his training wasn’t over, he knew he needed to heal or he would wash out. The physical pain gave way to a new psychological torture.

As early as Oct. 10, 2019, Jones started reaching out to his commanders for help, according to excerpts of internal Marine records obtained by Voice of San Diego. It’s unclear exactly what help he received or whether military leaders followed Camp Pendleton’s own mental health guidelines.

Jones asked to see a psychiatrist, his records indicate. Instead, he saw a chaplain.

“The chaplain read him a few bible verses, gave him some tapes and sent him on his way,” said his sister August Anderson, who was talking to him on the phone almost every day.

Jones’ combat training began on Oct. 16, six days after he started asking for help.

Jones’ dream was now dependent on his body’s performance and he wasn’t sure his body would come through. He talked to a gunnery sergeant about the possibility of dropping out, his sister said, which at this point seemed very real.

Photo courtesy of Brandy Altschul

“It had been this kids’ dream to be a Marine his whole life and he finally got there and his dream became the thing that was destroying him,” said Anderson.

On Oct. 18, he participated in a live-fire training event with his standard-issue M16A4. At the end of live-ammo trainings, military personnel conduct a “shakedown,” to retrieve all live ammunition. But the shakedown failed. Jones managed to hold on to a round, Marine records indicate.

He wrote a letter to his family. “I tried reaching out for help,” he wrote. “Everyone kind of ignored it.”

At 4:30 a.m. on the 19th, several Marines heard a loud sound, but assumed it was related to training exercises. Jones wasn’t found until 5 a.m., when he was marked absent at muster. He died three days later.

“He was a sweet kid. He would do anything for anyone. It’s not fair that he got destroyed the way that he did,” said Anderson.

Camp Pendleton is one of the most iconic military installations in the world, where mentally and physically fit young people train to be warriors. But an investigation by Voice of San Diego shows deadly mental health problems have been affecting the base for years.

At least 31 Marines, aged 18 – 25, died by suicide at Camp Pendleton between 2015 and 2020, according to San Diego County death records analyzed by Voice. That’s an average of more than five per year. At least 20 took their lives in Camp Pendleton barracks – and another four during training exercises.

Naval Base San Diego is home to almost as many troops as Camp Pendleton, but has not experienced nearly as many suicides. (Roughly, 40,000 troops were stationed at Camp Pendleton in 2019. Roughly, 33,000 were stationed at the 32nd Street Navy base.) From 2015 to 2020, only two young service members died at the 32nd Street base.

“Those numbers reflect a serious, persistent and tragic problem, with concrete cultural change long overdue,” M. David Rudd, a former Army psychologist and former president of the University of Memphis, wrote in an email, in response to Voice’s findings.

The barracks suicides are particularly disturbing, since barracks housing comes with multiple restrictions designed to keep troops safe. Marines living in barracks are not allowed to have firearms and they have limited access to alcohol, both of which can put people at greater risk of taking their own lives.

Most soldiers, and many members of the public, believe having access to a gun does not increase someone’s chances of suicide. But studies have shown that in fact it does. Easy access to a loaded weapon can enable a split-second decision to end one’s life. Men who own handguns are eight times more likely to take their own lives than those who don’t, one study found.

I asked Mario D’Aliesio, branch head of behavior health for Marine and Family Programs at Camp Pendleton, whether he found the string of suicides shocking or disturbing.

“Does it seem shocking? I don’t know,” he said.

When pressed on Camp Pendleton’s responsibility to prevent suicides, D’Aliesio said he believes the base’s current programs are working. He expressed a fatalistic view of Marine suicides.

“So here’s the thing: that free will and choice. When they make that decision to go, they’re not going to advertise it,” he said. “Very rarely is there that cry for help. If they wanna go, they’re gonna go. They may have done it before and then we can prolong that life. But then when they make that decision, they’re going to be alone.”

D’Aliesio referenced one component of Camp Pendleton’s mental health procedures that he believes is particularly well designed, several times. If a Marine asks for mental health services, they are supposed to be sent to a counseling center for an evaluation by the next day. No appointment is required. That evaluation, D’Aliesio said, will determine how quickly they can get an actual appointment to see a licensed therapist.

A Marine in severe distress, for instance, would be scheduled to see a counselor right away. Others might need to wait as long as eight weeks. The average wait time is 19 days, D’Aliesio said.

But in Jones’ case, it’s unclear whether the procedure, however good on paper, was actually followed.

Jones’ medical records contain no indication he ever received an evaluation, his mother said, even though he expressed mental health concerns multiple times over a nine-day period.

A Marine spokeswoman did not respond to a request for comment about the specifics in Jones’ case.

Pendleton clearly has mental health infrastructure. There are more than 100 certified counselors, dedicated to everything from stress to child welfare and substance abuse, said D’Aliesio.

But if there’s a disconnect that prevents services from reaching those that need them, many former service members say it is cultural. The demands of a warrior culture – in which soldiers are trained to put themselves in danger for the good of the whole – inherently conflict with expressing vulnerability and reaching out for help.

“You’re trained to bottle up your emotions and keep pushing from day one,” Matt Donohoe, a former Marine, previously told me. “Don’t get me wrong, the military has huge amounts of resources. You see it everywhere on suicide and harassment. They preach about open doors and how ‘You can come talk to us anytime, about anything.’ But it doesn’t work like that.”

D’Aliesio said he doesn’t believe there is a conflict between warrior training and reaching out for help.

Warriors are trained to tune out some pain, but they reach out when the pain becomes too great, he said.

“It’s like driving your car, when the little yellow light comes on, because you need to rotate your tires. That’s different than when the red light comes on because you, you don’t have oil in your engine. So, it depends on what’s going on at the time,” he said. “They can ignore it as much as they can. And even if they ignore it until their 19th year of their career and then say, ‘Hey, I better take care of this before I get out.’”

The problem is that some people aren’t reaching out when the light turns red. Or if they do, like Jones, they aren’t getting the help they need. Suicides, by and large, aren’t affecting people in the 19th year of their career. The problem is isolated among the military’s newest recruits – a trend that is obscured by military reports, which show the suicide rate for active-duty service members on the whole, when adjusted for age and sex, is roughly on par with the rest of the United States.

Young men in the military, aged 17 – 25, were almost twice as likely die by suicide as their civilian peers, previous reporting by Voice revealed. The majority of these young troops haven’t done combat tours, they are surrounded by other people who understand the unique pressures of military life and, in theory at least, they have direct access to the services they need.

It is absolutely possible to bring down suicide rates in the military, said Rudd, the former Army psychologist – especially on military bases themselves.

“You would have a range of appropriate expectations on any military facility, including: greater control over personal firearms and safe storage, easier access to mental health care, greater opportunity to [have] social support and recognize someone at risk, and a culture geared toward suicide prevention in recognition of the serious nature of this problem,” he wrote.

The number of deaths at Pendleton, he wrote, “raises broader concerns about installation culture.”

In the case of Jones, who died by suicide in 2019, Marine officials cleared themselves of any wrongdoing in their internal investigation.

“Despite Pvt Jones’s claim… ‘I tried reaching out for help. Everyone kind of ignored it,’” Pvt Jones received appropriate and timely medical care and counseling (sic),” the report notes.

The investigation recommended student Marines involved in training be manually or electronically scanned for loose rounds after completing live-ammunition trainings. A Marine spokeswoman did not respond to a request for comment on whether the change was ever implemented.

If you or someone you know might be considering suicide, please call or text 9-8-8.

This story was completed with assistance from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

[This story was originally published by Voice Of San Diego.]