Pennies On The Dollar: How Minnesota's Estate Recovery Program Helps, and Hurts, Vulnerable Residents

Kyeland Jackson's reporting on estate recovery was undertaken as a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 Data Fellow.

Other stories include:

When Kevin White talks about his family home, a smile creeps onto his face.

The Minnesota native created memories here. White's father built the house in the '60's, tucking the property amid the quiet forests and winding hills of Mazeppa, Minn. An old oven sitting unused in the corner reminds Kevin of his mom. The smell of her fresh-baked bread would waft through the house, luring Kevin and the handful of kids that his mother would babysit. A chair gathering dust in the corner brings memories of his dad, who would whittle away for hours to create wood carvings. The home has been a foundation in White's family and community for decades, and he plans to pass it on to his son. But a controversial federal law known as estate recovery could cancel Kevin's plans.

Kevins' mother was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in 2017, and treatment was expensive. Kevin spent more than $15,000 to help her, but other healthcare services she received made her home eligible for estate recovery. It's a program that claws back what the county spent on long-term care for Medicaid recipients by laying claim to their property. After two years of treatment, the state said that his mother's medical costs totaled $187,000 – and a lien would be placed on his family home to help pay for it. Because his mother gave him the home months before she died, Kevin was asked to pay for the lien. But when the housing market boomed along with his home's value, Kevin got a new letter from the county which said the lien amount had now doubled.

"I did exactly what they told me to do, then when I went and had it appraised, they backed out of the deal," White said. "It's changed my view of the state to where I think they're crooked. I don't trust them at all anymore."

Northeastern areas in Fresno County and some of northwestern Fresno County on average had the highest rates of additional emergency room visits on extremely hot days in Fresno County between 2009-2018. Courtesy of Dr. David Eisenman.

He may not be the only one.

Minnesota's estate recovery program has grown into a complex machine funded by families with moderate income. Experts say Medical Assistance recipients are often not informed and not able to pay back their debts, deepening wealth inequality between generations. And although the program is meant to help future Medicaid recipients, loopholes allow people to receive taxpayer-funded medical expenses while skirting the rules of estate recovery.

"The longer [programs] are around and the more things that get added and changed, they just get more and more complex. The average person has no ability to be able navigate through it," said Jason Rarick, a Republican state senator from Pine City, who is pushing to limit estate recovery. "Those who can afford, they can hire the people that know the system and they know how to game the system."

The Argument For Estate Recovery

Since the 1960's, when Kevin's father built their house, Medical Assistance has been a safety net for low-income Minnesotans. Medical Assistance is the state's version of Medicaid, and its estate recovery program began after federal law allowed states to recoup medical benefits spent on people with Medicaid. It became a source of revenue for states, and a way to get vulnerable family members out of almshouses, early versions of nursing homes which eventually fell into disrepair. As the Minnesota Supreme Court said while defending the program, "[Estate collection] is a system whereby money paid to qualified individuals for healthcare purposes may be recovered and reused to help other similarly situated persons."

That system has recovered a lot of money.

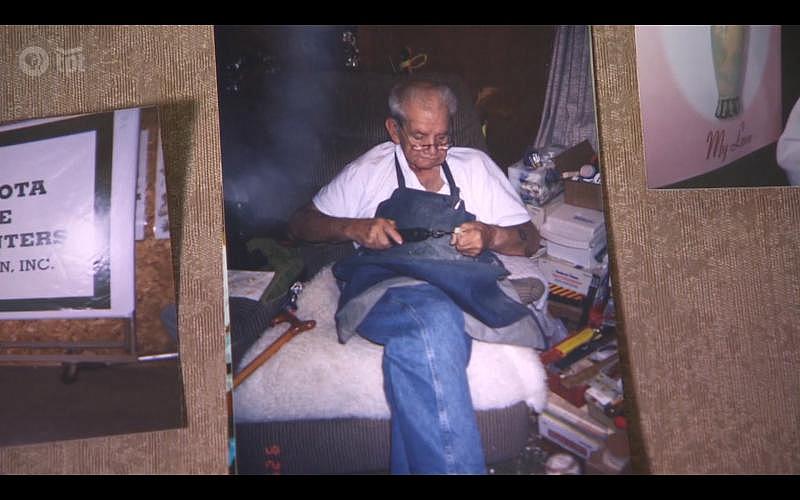

Kevin's dad, Marvin White, whittling away in his favorite chair.

In recent years, estate recovery has raked in $265 million from the estates of dead Minnesotans. Much of that comes from counties across the state that keep a quarter of the funds collected from estate recovery. Those funds are also a boon for current Medicaid enrollees, who make up more than a million Minnesotans in any given month, according to 2020 data provided by the state.

Although the program benefits some healthcare recipients, cracks in the program's effectiveness have surfaced. Federal law made the program mandatory in 1993, as the nation tried to lower its national debt through fees and program requirements. West Virginia sued the federal government shortly after that, saying the estate recovery requirement was a "betrayal of The New Deal." The state lost. Michigan delayed estate recovery until 2007, when the federal government threatened to pull its Medicaid funding. And data shows that the money Minnesota's estate recovery system makes is less than 2% of what the state and its counties spend on long-term care for people on Medical Assistance. In fact, spending on long-term care for Medicaid recipients has steadily grown.

States must continue the program if they want federal dollars to flow. But attorneys say that estate recovery hurts some of their most vulnerable clients the most. Laurie Hanson and Laura Zdychnec are two of those attorneys.

Uninformed and Unprepared

Hanson and Zdychnec have met many people like Kevin White. The attorneys' combined experience of 67 years in law is represented through the Minneapolis firm they created for aging clients. As taxpayers, they said they have no issue with the concept of estate recovery. But the way that it's executed raises legal and ethical concerns for them and their team.

"Federal law is pretty clear that people need to be aware of, and given notice of, the state's estate recovery program when they apply for Medical Assistance. That notice is in some cases lacking entirely, and in some cases it's pretty deficient," Zdychnec said. "I'm not suggesting that people never are aware of what's coming at them, but I think, in my opinion, the state needs to do far more to inform people up front of how [this program] really operates and what the expectation will be on the other end."

Kevin points to a picture of his mom, Catherine White, sitting in their family home. Kevin was prepared to pay off a lien the state placed on the house after she died, but was caught by surprise when the state doubled his lien amount.

In some cases, Hanson said that entire generations are displaced because the home that they live in is the only asset that they have – and they don't learn about estate recovery until it is too late. The fact that few Minnesotans know about estate recovery is backed by a 2021 report to Congress by the nonpartisan Medicaid and Chip Payment and Access Commission. They found that few people across the nation know about estate recovery, and many with wealth are avoiding recovery programs entirely. That comes at the expense of families with modest income, a fact which attorneys like John Kantke know all too well.

Loopholes exist. But how to close them?

Kantke is a guardianship attorney who practiced elder law and represented aging Minnesotans for more than a decade. He believes Medicaid is a good alternative to almshouses, which sometimes barred people from Social Security. Still, he says that Medicaid and its recovery program have issues.

To qualify for Medical Assistance, people must get rid of most of their assets and spend down to their last $3,000, depending on their circumstances, five years before they enroll. Those who break the rules can be hit with penalties, which include the state refusing to pay for some Medicaid expenses. The restrictions were meant to penalize people who exploit the system, but Kantke found that those who can afford a good lawyer can find ways of qualifying for Medicaid without losing their wealth to estate recovery. Whether that is through cabin trusts, non-profits or other financial loopholes, it's a comfort which Minnesota's more vulnerable recipients cannot access. Estate recovery's loopholes, and the burden they place on low-income families, are part of why Kantke says the program is "regressive."

"I think it's hitting those with the least amount of money the hardest," Kantke said. "When the system is taking 100% from some and 10% from others, it seems unfair."

State officials are very aware of these loopholes. They say they have worked hard to close them and make the program more equitable, but that's easier said than done.

Geneva Finn is the Special Recovery Unit Manager for the Department of Human Services. She and six staff members help to run Minnesota's estate recovery program, which sprawls from Wabasha County, where Kevin White is fighting for his family home, to every county across the North Star State. Finn said that they're concerned about cabin trusts and other financial loopholes, but her office is short-staffed and under-resourced. With so much to manage and so few resources to manage them with, the state leaves a lot of data collection to the counties. As a result, escape routes from estate recovery, such as hardship waivers and appeals, are decided by county officials with little state oversight.

"Counties track their estate recovery program internally. Some counties are in paper file. Some counties have various databases set up," Finn said. "You could have your hardship waiver granted – it wouldn't go to our appeals office, it would just go to the county office. It would just happen on the county level, and I wouldn't necessarily have reason to know about it, unless there was some question about it."

In some ways, the difference between Minnesota counties' recovery programs is a microcosm for estate recovery in different states.

In Kittson County, where the population is small and the median household income is around $55,000, estate recovery is run by three people. Their county recovered the least from Minnesotans in recent years. The median household income average person in Hennepin County is $81,000. Their estate recovery program collected the most money from the most people in recent years: $42 million from 8,500 people. And data from Itasca County shows that a third of the cases they tried to claw back weren't recovered at all. Officials there declined to be interviewed because, they said, resources weren't available. You can find how much your county recovered, and how many people they recovered from, below.

With such a gulf of difference in the efforts counties rely on, Minnesota State Senator Rarick says it makes sense that communication from those officials is lacking. Rarick is lobbying to close a different loophole in estate recovery, and believes that smaller counties don't have the workforce to better execute estate recovery. Still, he says it's a failure if people are not told that their estates will be clawed back, adding that it's on government officials to make constituents feel heard.

"It doesn't seem like there is good communication sometimes, within a state agency and especially across agencies … I think that's what gets very frustrating for a lot of people," Rarick said. "If you don't think you're being listened to, the initial reaction is that 'they don't care.'"

Rarick said that national conversations about estate recovery could gain traction in Minnesota. One federal bill co-sponsored by U.S. Rep. Ilhan Omar, a Democrat representing Minnesota's 5th Congressional District, could do that and more: It could overturn the federal mandate for estate recovery, and give all states a chance to end their programs.

Kyeland Jackson's reporting on estate recovery was undertaken as a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 Data Fellowship Grantee.

[This article was originally published by TPT Originals.]