Pharmacists are now poised to ease physician shortage—if only they could get paid for it

This story was produced as a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism’s California Fellowship.

Other stories in the series include:

When it comes to doctor access, the San Joaquin Valley is being left behind

With limited federal funding, Valley struggles to expand medical training programs

Brian Komoto, pharmacist and CEO of Komoto Healthcare, runs Komoto Pharmacy in downtown Delano.

When we consider medical providers, what comes to mind may be doctors, nurse practitioners and physician assistants. But what about pharmacists? A new law has allowed them to greatly expand their role to become providers—which could be good news for patients struggling to access doctors. But one major obstacle still stands in the way of pharmacists taking on patients. This latest installment of our series Struggling For Care begins with the story of a community pharmacist in Kern County looking toward the future.

Behind the cash registers in an expansive blue-roofed pharmacy, two huge machines are whirring away, filling little plastic bottles with pills, tablets and capsules of all sizes and colors. “These are robots, auto-fill robots,” says Brian Komoto, the CEO of Komoto Pharmacy in downtown Delano and its parent company, Komoto Healthcare. “If [pharmacists] want this prescription, they scan it, it shows what the tablet should look like so they can compare, and then they cap it.”

A pharmacist and entrepreneur, Komoto’s worked hard to make his pharmacy stand out. He offers wheelchairs, walkers and other aids that typically aren’t available at retail pharmacies—and he was an early adopter of those fast-moving, prescription-filling robots that improve efficiency behind the scenes. “We try to think of: How do we raise our game? I want to be the Disneyland of pharmacy if I could,” he laughs.

Komoto is particularly excited about a new opportunity that could allow pharmacists across the state to up their game. Thanks to a law enacted in 2014, pharmacists have been upgraded from medical professionals to providers. Health leaders are excited about what this could mean for reducing the patient load of primary care doctors—but only once they overcome a major hurdle.

Credit Kerry Klein / KVPR

At a basic level, Senate Bill 493 sets out to make better use of what many say is the most accessible health care practitioner out there. After all, asks Virginia Herold, executive officer of the California Board of Pharmacy, what other practitioner can you see in your neighborhood, without an appointment, regardless of insurance? “I think their role in the health care field is tremendously underutilized,” she says. “It's not just what I'm saying, it's part of what led to the enactment of SB 493.”

Because of this law, pharmacists can now offer a handful of drugs without a prescription, including travel medications and immunizations. And it led to other laws that allow pharmacists to furnish birth control and the opioid overdose drug naloxone.

With some more qualifications training, pharmacists can also apply for an additional license to become an “Advanced Practice Pharmacist.” Those elevated pharmacists can work more closely with patients to monitor diseases and help manage drug side effects and complications.

Herold says SB 493 came about in anticipation of a run on doctors from the Affordable Care Act. “The whole point in having pharmacists involved in this is to help take care of some of the things that pharmacists are trained to do,” she says, “and to keep the primary care providers focused on the things that they are required and can do themselves.”

If pharmacists can see patients for medication-related requests that would normally require a primary care appointment, this could ease doctors’ patient loads. But this doesn’t mean pharmacists will replace doctors. The goal is for pharmacists to play a more integral role in managing patients alongside other providers.

Jennifer Toy, a professor at the UCSF School of Pharmacy and a pharmacist at Kaweah Delta Medical Center in Visalia, says many hospital-based pharmacists already have protocols that allow them to work in tandem with doctors and other providers. “I really think of us as a member of the team, but like a bridge,” she says. “Let's say a physician has 15 minutes to see a patient for diabetes. Oh, but the physician's schedule is now full and can't see the patient for another month. A pharmacist can step in, has more time—30-60 minutes at my clinic—and can see the patient every week until they can see the physician again.”

Some places poised to benefit most from this law are underserved areas where there’s typically fewer providers, fewer hospitals, and patients with a high burden of chronic disease. “In areas where the physician shortage is harder hit than some other areas, such as the Central Valley, I think those are going to be probably the places that’re most likely to be positively impacted,” says Stanley Snowden, a pharmacist at Community Regional Medical Center and a professor at California Health Sciences University’s College of Pharmacy in Fresno.

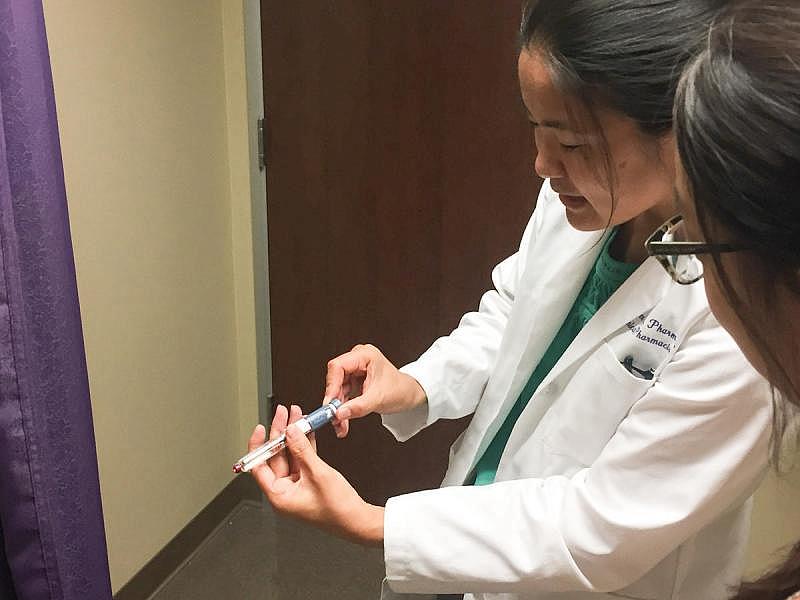

SB 493 now authorizes pharmacists to furnish some medications without a prescription and work directly with patients to manage their medications. In some settings, pharmacists are already permitted this expanded scope of practice—including Jennifer Toy, a pharmacist at Kaweah Delta Medical Center shown here demonstrating how to use an insulin pen. Credit Matt Heinsen

But if you haven’t heard of this expanded role for pharmacists, that’s because it’s not exactly being advertised. Lisa Kroon, chair of the department of clinical pharmacy at UC San Francisco, says there’s a bit of a problem. “One of our main barriers has been Medicare,” she says. “On the federal level, to be a prescribing provider, we are not recognized by Medicare, or the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and that limits us in terms of billing for our professional services.”

This is so new, pharmacists aren’t yet paid for these services. They can’t bill private insurance plans for them, and can’t get reimbursed by the government. “So it makes sense that in terms of providing this service, we need to get paid for it before you're going to see a large chain necessarily adopt it,” Kroon says. “But we're making progress.”

A state law passed last year authorizes pharmacists to be reimbursed through Medi-Cal, but that can’t go into effect until the state develops a policy proposal and gets it approved by the federal government. A state representative informed me it’s likely their submission won’t be ready until at least mid-2018.

Simultaneously, two bills in Congress propose reimbursing pharmacists in medically underserved areas but haven’t yet to come to a vote.

Meanwhile, local pharmacists are stepping up. Of the 45,000 or so pharmacists in the state, only about 150 have sought out Advanced Practice Pharmacist licenses, which have been available since January. Six of those pharmacists are in the Valley. In fact, Kern is among the top 10 counties in the state for its number of Advanced Practice Pharmacists, and Bakersfield has the same amount as San Francisco.

One of those pharmacists works for Brian Komoto, who’s already preparing for taking on pharmacy patients. Eventually, he thinks they’ll have the space to take on two patients at a time in their Delano pharmacy. But only once they can start getting paid for their work.

[This story was originally published by KVPR.]