The Pleasure and Price of Longevity

The story was co-published with The Observer as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

The Francis family is the embodiment of the term “growing old together.” From left are Anthony “Tony” Francis, 97; Shirley Francis Wade, 90; and Veronica Francis LaRue, 94. Tony Francis holds a photo of their sister Althea Francis Bell, 92.

Photo: Robert Maryland, OBSERVER

Whether it’s a closely guarded holiday recipe, a cherished piece of jewelry or a parcel of land somewhere down South, Black elders usually try to leave their people something.

George Francis blessed his offspring with the gift of long life. Before Francis died in 2008 at the age of 112, he enjoyed his status as the oldest known man in the country and second oldest in the world. All four of his children are in their 90s. The oldest, Anthony “Tony” Francis is 97. They call him “The Pioneer.” His “baby” sisters Veronica Francis LaRue, Althea Francis Bell and Shirley Francis Wade are 94, 92 and 90, respectively.

The four grew up surrounded by other Creole families in New Orleans’ Seventh Ward. The neighborhood offered humble beginnings for such notables as jazz icon Jelly Roll Morton, rapper Mannie Fresh, author and culture commentator Melissa Harris-Perry, and award-winning playwright and filmmaker Tyler Perry (no relation).

“We were po’,” Francis says.

Translation, they couldn’t even afford the “or.”

“We used to wear other people’s shoes. Shoes would be given to us,” Francis Wade adds.

Tony Francis was the first of the siblings to move to Sacramento, joining their father who’d previously moved to the capital city looking for work.

“I wanted to get things better for us,” he says.

At their advanced ages, the siblings, and their extended families, remain close. All but Francis Bell live in greater Sacramento. Her daughter transports her to and from Southern California a few times a year, so she can be with the rest of the close-knit family. She ventures north for birthdays and holidays. The family also gets together for dinner every Sunday. The raucous sessions allow them to bond over shared memories and a big pot of Creole gumbo.

The family dinners are held at the LaRues’ home, which is filled with countless family photos from throughout the last century. There are also several instruments about, including a set of drums and a piano. Francis doesn’t need much encouragement, but he may be asked to sing or whistle. The eternal song in his heart, he says, was fostered by his mother, Josephine.

“I’d watch her doing the scrubbing and she would sing, ‘What a Friend We Have in Jesus.’ It was always stuck in my head and every now and then I sing [it],” Francis says.

While he can’t recall that Ephraim David Tyler wrote it, he often recites every word of his father’s favorite poem, “A Black Man’s Plea for Justice.”

“I consider those to be contributions from them to us,” he says.

He and his sisters also remember their aunt Lena, who loved scotch and played poker. As children of that era, they weren’t supposed to know that, but they have fond memories of her exploits.

The siblings all inherited their mother’s love of music and often performed together around the house, Jackson 5 style, though they predated the famous brothers by more than a decade.

“We were better than them,” chimes in Francis Bell.

Boundless Affection

Shirley remembers trying to get Veronica, whom she lovingly refers to as “the perfect one,” in trouble back in the day.

Veronica Francis LaRue and her siblings are living history lessons. They’re living their best lives despite the aches and pains of aging.

Photo: Robert Maryland, OBSERVER

“The [Catholic school] nuns taught us about all these things that were sinful – like it was sinful to wear nail polish, it was sinful to cross your legs. I was always tattle-telling on her,” Shirley says.

“It seems ridiculous now. Veronica always was sweet and quiet – she still is – but she can surprise you. With me, what you see is what you get.”

LaRue interjects: “What she’s trying to say is, ‘With me, you don’t know what you’re going to get.’”

The siblings playfully tease each other like they’re still youngsters, a deep affection evident in their banter. Their playful ribbing hints at the enduring bond they share.

As children, that closeness was more literal, as all four of them had to share a bed.

“He never complained,” Shirley says of her older brother, recalling times the girls’ feet “accidentally” connected with his mouth as he laid at the opposite end.

Today, Shirley, the “baby” of the bunch, lives independently with her husband, is virtually wrinkle free at 90 and still drives her own car. Veronica lives in Mather with her son, Glenn Marlowe Stephens. She’s using a wheelchair as she heals from a recent fall. Before her injury, she managed with a walker.

Tony lives in a senior living environment, has hearing aides and uses a wheelchair when he needs to. Independence is important to him.

“One of the things about this whole longevity and living until you’re 100 years old is that you lose things,” he says. “Some things just leave you. You lose your memory, your mind, your appetite. You lose a lot of stuff. That’s one of the things I try to keep as much as I can. In the process, I pay a price.”

Age: Take It Personally

Francis Bell is also a member of the “walker club.”

Shirley Francis Wade, pictured, her brother and two sisters are the heads of their own families. Their extended circle includes countless grandchildren, great-grandchildren and, soon, great-great-grands.

Photo: Robert Maryland, OBSERVER

“It’s physically where we are, but it doesn’t beat us down,” she says. “That’s why I go to metaphysics: mind over body. I think I talk for all of us. We know where we are in our lives right now, but we handle it in the best manner. I’m proud of my siblings because of the route we have taken to being positive.”

Francis Bell admits to a few “bad habits” like a penchant for casinos, but says at her age, she’s focused on being as well as she can be, for as long as she can be. For her that means taking regular naps, a daily aspirin regimen, cooking with herbs and spices that promote health, and keeping a journal of certain bodily functions.

Shirley says she was “shocked and annoyed” to hear a friend once say, “Oh, Shirley, we sure are old, aren’t we?” They were 60 at the time.

“That wasn’t extremely young, but it wasn’t really old either,” she says. “I was like, ‘Speak for yourself.’”

The friend died shortly after that.

“It’s a mindset thing, too,” Shirley says.

“The aging process is a very personal thing,” Tony says. “Some people feel old at 60 and some feel very young at 60. In my own case, I feel that my life has turned around in a sense that I am younger as I get older. Younger in mind, but not in body.”

Five years ago, Tony Francis joined “Life After 90,” a research study conducted by UC Davis. The study, funded by the National Institute on Aging, focuses on the understudied population of elderly people of color and low-income individuals who are experiencing mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Francis is among hundreds of participants who are interviewed every six months.

“They’re looking into racial differences and how they affect the aging process,” Francis says. “What percentage of Blacks live shorter lives? Blacks seem to have the shortest lives and that’s often related to low incomes and low education.”

Francis argues that the “powers that be” don’t pay enough attention to the health needs of Black seniors.

He won’t be around to see the “Life After 90” research results, but finds satisfaction in the notion that his experiences can contribute to the well-being of future generations. Being a part of the process is his way of leaving a legacy.

“This is about the fourth research study I’ve been in,” he says. “They’re very worthwhile, and I intend to continue that now as far along as I can.”

‘He Never Said The Word’

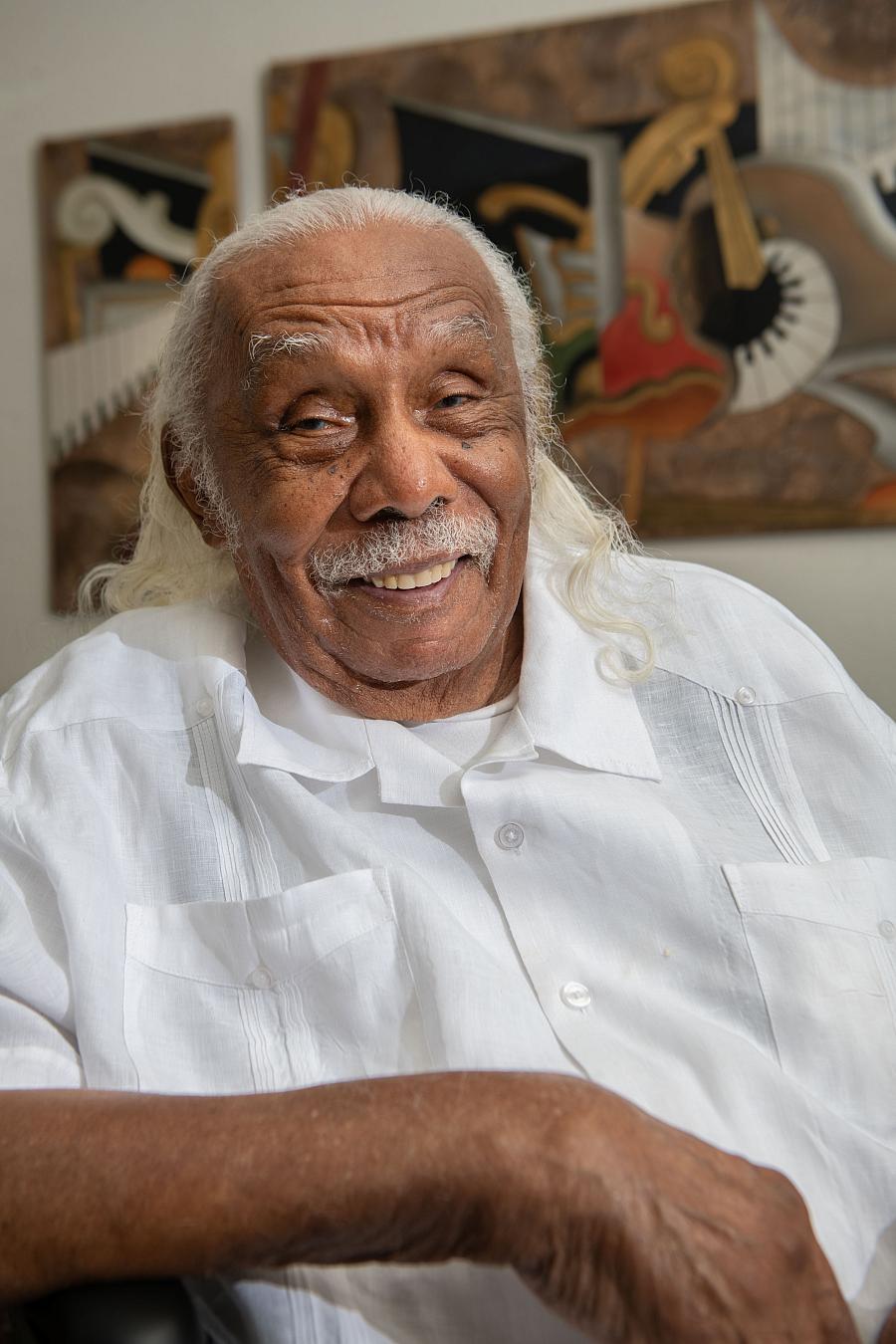

Anthony “Tony” Francis’ mind is sharp at 97. He speaks and sings in French and participates in aging studies.

Photo: Robert Maryland, OBSERVER

Over the years, Sacramento has had its share of centenarians, including a number of African Americans. Among them have been Mother Ruby Muhammad, a revered elder in the Nation of Islam, who reportedly was 114 at the time of her 2011 passing, and Mother Barbara Holman, who celebrated her 110th birthday in July.

Francis, who is closing in on centenarian status himself, recalls attending an annual centenarian dinner co-hosted by the Area 4 Agency on Aging in celebration of his father. He also helped organizers find other Black seniors to recognize.

“We did a good job, he says. “The banquets were always crowded.”

The events ended before George Francis became a super-centenarian, a distinction given to those who reach 110. He has been gone for 16 years, but his children still look to his example.

“He never mentioned age,” Francis Wade says.

Francis LaRue agrees.

“He never said the word ‘old’ ever,” she says.

“That may be one of the secrets to growing old,” her youngest sister says.

The family of seniors is acutely aware of the challenges associated with aging and outliving many of their loved ones.

“We’ve lost a lot of friends and relatives that we were close to,” Veronica says.”We have children in their 70s.”

“My sisters, they had to run fast, but they caught up with me,” Tony says, catching the ire of one of those sisters.

Clearly, laughter is a large part of their lives and their longevity. That and their love for each other.

“It’s the bonding,” Francis Bell says. “Family is big time and I don’t mean just sisters and brothers. It took the family to raise the whole family and we had one large family. We’re blessed.”

EDITOR’s NOTE: This article is part of OBSERVER Senior Staff Writer Genoa Barrow’s series, “Senior Moments: Aging While Black.” The series is being supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California. The OBSERVER is among the collaborative’s inaugural participants.