A Portland diabetic Native American mother risks difficult pregnancy for fresh start

By most measures, Native Americans' health problems exceed the average, and it's even worse for urban Indians who can't tap social and health services available on distant reservations. About 2 percent of Portland's metro area 2 million population identify as Native American or part Native. That amounts to about 30,000 of 102,000 statewide, including nine reservations.

The series Invisible Nations Enduring ills focuses on the often-overlooked minority of urban Native Americans and their enduring health disparities.

Part 1: Portland-area Native Americans burdened by health hurdles generation after generation

Part 2: Portland-area Native Americans take on a diabetes epidemic

Part 3: Native Americans strive for health against alcohol, chaos and trauma

Part 4: A Portland diabetic Native American mother risks difficult pregnancy for fresh start

Part 5: Alaska Native Medical Center a Model for Curbing Costs, Improving Health

The doctor confirms Candida KingBird and Bruce McQuakay's good news: a child on the way.

But Oregon Health & Science University physician Jorge Tolosa, a specialist in preterm births, warns it's a high-risk pregnancy.

KingBird, 38, has lived a decade with diabetes and has five children, the last of whom nearly died from problems related to the disease after a cesarean section.

She and McQuakay, 30, lean and reserved, met a year earlier during the intense Sun Dance ceremony on Mount Hood. They found a bond in their Native American culture and spirituality. She is Ojibwe; he has the blood of four tribes, including Cree and Tlingit. She likes that he has completed high school, has silversmith skills, helps lead the Sun Dance, dances in full regalia at powwows and has been sober more than two years.

KingBird has struggled against her share of forces that disproportionately undercut health for Native Americans: foster care, parental neglect and abandonment, teen motherhood, domestic violence, addictions to drugs and alcohol, and diabetes.

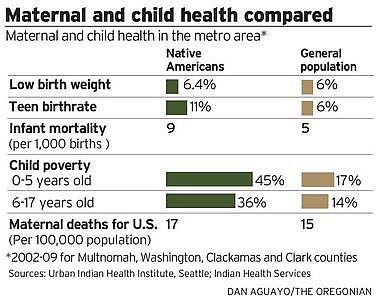

Native Americans have high rates of at-risk pregnancies, as they do other health problems. Compared to the general population, the 30,000 Natives spread thinly over the four-county metro area have significantly higher rates of obesity and diabetes and double the rate of teen births and infant mortality.

Precise figures are elusive because urban Indians are widely misidentified and miscounted, though the trend is unmistakable.

KingBird's risks are manifold. She faces higher risks of stroke, heart and kidney failure and infections. Her cells could starve for sugar, producing diabetic ketoacidosis, characterized by fever, dehydration, problems breathing and, in extremes, death.

KingBird's diabetes likely will cause her baby to grow larger than normal and to be delivered before the full 40 weeks.

Her newborn will be vulnerable to life-threatening low blood sugar as it compensates for the mother's high sugar levels. Later in life, the child would be more likely to have chronic illnesses, including diabetes.

In late October, she's admitted to OHSU with sky high blood sugar and blood pressure. An insulin drip and special diet stabilize her. Ten days later, she's admitted with an abscess in her mouth. On Dec. 28, she's back with an upper respiratory infection and blood sugar out of control.

She's released New Year's Eve and heads for the Native American Rehabilitation Association (NARA) of the Northwest annual powwow at the Oregon Convention Center. Scott Buser, NARA's treatment director and recovered addict, has started the sobriety countdown by inviting the person with the longest sober stretch to step into a dimly lit powwow circle fringed by a thousand chairs, most occupied.

Out steps a bony elder. He leans on a walking stick and wears a gray beard, a NARA T-shirt and black cowboy hat. Clean 46 years, he says, as the exhibit hall fills with applause. Buser then calls out the years, 45, 44, 43, 42...as Native el

The countdown has reached 10 days when KingBird arrives. About 200 of the recovered move in two circles, one rotating inside the other, those in one shaking hands with those in the other. Kingbird steps up to Buser's microphone: "My name is Candida KingBird, and today is my seventh sobriety birthday."

By 16, she was a single mom, living with her daughter above the tavern where she waited tables. Two years later she was pregnant again and getting beat up by her baby's father. She fled to a group home, earned her GED and delivered her first boy.

She moved to be close to relatives in Fresno and delivered a second son from another abusive boyfriend. The boyfriend would punch her in the face while she was in her bed.

"I would wake up bleeding," she says

KingBird later moved to her hometown of McMinnville. She developed gestational diabetes during her fifth pregnancy and delivered her 10 1/2 pound girl by cesarean section five weeks early. The daughter barely survived.

Over the next years, KingBird slipped into drug and alcohol abuse. In 2004, she entered rehab at NARA where treatment is integrated with Native traditions.

"I realized I lost a big chunk of myself when I moved out of Minnesota," she says. "I had a spiritual and cultural hole that only the Creator could fill."

Her own trauma, though, keeps her up nights. "I'm vulnerable when I sleep."

KingBird checks in at the high-risk pregnancy center weekly and logs her blood sugar through the day and night. She injects five to seven shots a day of insulin, which hormones from her placenta render less effective.

In February, Dr. Brian Shaffer, specialist in high-risk pregnancies, runs an ultrasound wand over her rounded belly and checks out the six-month old fetus, clearly a girl. KingBird can see the images of her child on a monitor. Shaffer looks at the baby's tiny beating heart, brain, kidney, blood flow.

"All is normal and good," he says. "I don't see anything that concerns me other than she is big, and I think we know why."

KingBird's high blood sugars are reaching the baby, causing faster-than-normal growth. Shaffer says the baby weighs 2 pounds, 3 ounces.

Later, Dr. Susan Tran talks to KingBird and warns her she is highly insulin-resistant and her blood sugar is too high. KingBird says she's walking more, watching her diet and has lost five pounds.

"I park way at the end of the parking lot," she says. "I'm constantly on the go. I work in the field most of the time. My diet has been good."

"I'm not saying these things to make you feel bad," she says.

"It is really hard," KingBird says.

"It is a chronic disease," says Dr. Tran. "You are going to have it for the rest of your life. It is silent. You don't feel it."

"My grandma is 86, and she got her leg amputated last month" because of diabetes, KingBird says. "When I saw her last weekend, she started to cry, 'They cut off my leg.'"

"That is really too close to home," says the doctor. "You have a choice. You know this will not go away...Why can't we get this under control?"

It gets so far out of control that KingBird's back in the hospital on April 7. She's also having early Braxton Hicks contractions that prepare the body for delivery. She's frustrated and alone.

"I have to get a wheelchair for myself," she says as she leaves for home. "There is no one strong enough to help me."

The Plan

Dr. Tolosa sees KingBird five days later and summarizes the status of her pregnancy. The baby is large, but the morning's ultrasound shows she is stable in plenty of amniotic fluid. She has reached the 32-week mark.

"We are seeing the summit of the mountain we are climbing together," Tolosa says.

She needs to start visiting OHSU twice a week, he says. The placenta starts working less efficiently at this point, and she could develop preeclampsia, which relates to increased blood pressure and protein in the mother's urine. It can damage the placenta and affect KingBird's kidney, liver and brain. It can progress to eclampsia, which causes seizures and is the second leading cause of maternal death in the United States.

If her baby grows too big, it could rupture the scar from her previous cesarean section, cause bleeding and possible death to both mom and daughter. Tolosa wants to deliver on May 11 at 36 weeks, but there's a chance the baby's lungs might not be ready.

"So we're balancing your health and well-being, and the baby's," he says.

He proposes a plan. He wants to bring KingBird into the hospital the day before, make sure her sugar level is good and take a sample of her amniotic fluid to test for lung development. If the lungs are ready, they deliver the next day. If she and the baby are stable, but the lungs are not ready, they could let them develop another week. Even then, they might not be ready, he cautions, because high blood sugar can delay lung maturity.

As she leaves the OHSU parking garage, her car is struck in a fender bender. Contractions begin, and she is admitted briefly to the hospital.

Two weeks later KingBird drives with a 17-year-old son, 16-year-old daughter and boyfriend to pick up her mom in Salem and see her grandmother, who is in a Salem rehabilitation center, recovering from her second leg amputation.

KingBird's baby has dropped in the uterus, and her cervix is effaced and slightly dilated, signs her body's preparing to deliver. Doctors have scrapped plans to hold out for 37 weeks. They'll deliver at 36 weeks, four shy of full term, on May 11.

The family finds Kingbird's grandmother, Louise Jones Rodriguez, in a lower-level, low-slung lobby, sitting at a table alone. She perks up as KingBird sits next to her, strokes her hair and tells her the baby is coming in two weeks. KingBird wheels her grandmother through a door to a patio outside under a large deck next to a grassy area.

She lights a bundle of sage, and moves it under her arms and around her grandmother so the smoke rises up around them. KingBird's mother and kids also smudge.

The tradition of smudging "purifies mind and spirit and carries your prayers up to the Creator in smoke," Kingbird explains.

Then she taps on a support beam in lieu of a drum and sings a woman's honor song to her grandmother in Ojibwe.

"Oh, that was nice, yaaaa," says her grandmother.

A week before her due date, KingBird is laid off after the Portland Children's Levy cuts funds for NAYA's foster care program. Two days before, she's hospitalized with preeclampsia. She's swollen, feverish and has protein in her urine. Doctors decide to act.

Early the next morning, two teams of doctors, anesthesiologists and nurses –about a dozen in all –prepare an operating room. One team will deliver the baby; the other will focus on making sure the baby survives.

An anesthesiologist tells KingBird she will be trying to give her a spinal shot that will prevent pain yet allow KingBird to remain awake. KingBird had problems with that shot during a previous delivery.

"I don't want to be poked and poked and poked," she says.

"We are not going to torture you," says Dr. Emily Olsen, an anesthesiologist. "We can take our time and do it right."

Dr. Lishiana Shaffer, who will lead the delivery, greets KingBird and McQuakay.

Shaffer warns the baby could end up in neonatal intensive care.

"Do you have a name?" she asks.

"Mishiike Mete," says kingbird. "Turtle heart."

The doctor asks what music they want for their birthday party.

"Northern Cree," says McQuakay.

At 9 a.m. on May 10, KingBird delivers 9-pound, 12-ounce Mishiike to the tune of Over the Rainbow. Doctors couldn't find Northern Cree.

The baby spends 36 hours in intensive care to restore her low blood sugar, a reaction to KingBird's diabetes, before going home.

Two weeks later, Mishiike has lost weight and is jaundiced. She has too much biliruben in her blood due to her earlier low blood sugar. Untreated, biliruben can cause brain damage. Doctors hospitalize the baby for three more days.

KingBird, who has private health insurance, arrives home with a healthy baby and a big hospital, prenatal and delivery bill: $106,233.

KingBird relaxes one June afternoon at her kitchen table in her East Portland apartment with her daughter Mishiike cradled asleep in her arm. Her oldest daughter is visiting. Her other children are scattered. One son is in custody of the Oregon Youth Authority. She says her younger teenage son is moody, embittered, difficult and has run away to the Warm Springs reservation. One daughter lives with her father; a grandmother cares for the other daughter. The grandmother she recently visited has died.

KingBird and McQuakay agree they have no future together. McQuakay, though, wants to be involved in his daughter's life.

"I don't want to perpetuate the cycle of not having parents, of not having a dad," says the father, who grew up in foster care. "I know the feelings I carry because of that."

KingBird is unemployed, on her own, contemplating her next move. She might look for work or go back to school, maybe to get her certification as an alcohol and drug counselor. She still has options, hope, a new baby.

"We don't get to choose where we come from," she says, "but we get to choose where we go."