Pricey housing in Napa County can cost more than your paycheck. It can affect your health

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Courtney Teague, a participant in the 2019 California Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Napa Valley strangers talk housing struggles over a pizza party

Local officials to discuss housing, take public questions at Register town hall

Housing costs cramp business in expensive communities

Renter’s handbook: Here’s how to navigate the top 6 tenant housing issues

Farmworkers, the backbone of Napa Valley's economy, face health challenges

Sean Scully, Register

Agustina Palafox has dreamed of owning a modest house or mobile home for all of her life.

Instead, the single mom of three from St. Helena said she spends many nights lying awake in her two-bedroom unit, her back sore from her part-time housekeeping job at a local winery, stressing about how she’ll come up with $1,750 for her monthly rent.

Palafox, 54, wishes that her income and work schedule allowed her to take her kids — ages 9, 12 and 14 — on trips to Disneyland, San Francisco or the Six Flags theme park in Vallejo. Her kids say that they wish their dad, who passed away two years ago, could take them places.

“I feel really sad because I can’t provide this for them,” Palafox said in Spanish, translated by Cristina Avina of UpValley Family Centers, a family resource center in northern Napa County. “I feel really stressed out and pressured … because I’m a dad and a mom.”

While rolling vineyards, and fine wines and dining come to mind when most of the world thinks of the Napa Valley, the financial burden that Palafox faces because of housing costs is not unusual here.

As part of a collaboration with the University of Southern California’s Center for Health Journalism, the Register has heard from nearly 200 people who shared their stories by responding to our questionnaire and recording themselves at equipment posted at the UpValley Family Centers offices.

Some said the county’s high cost of housing has affected their mental health. Others report sharing a bedroom with their family, being unable to feed their kids on some days, struggling to manage other expenses such as medical care and leaving the county altogether.

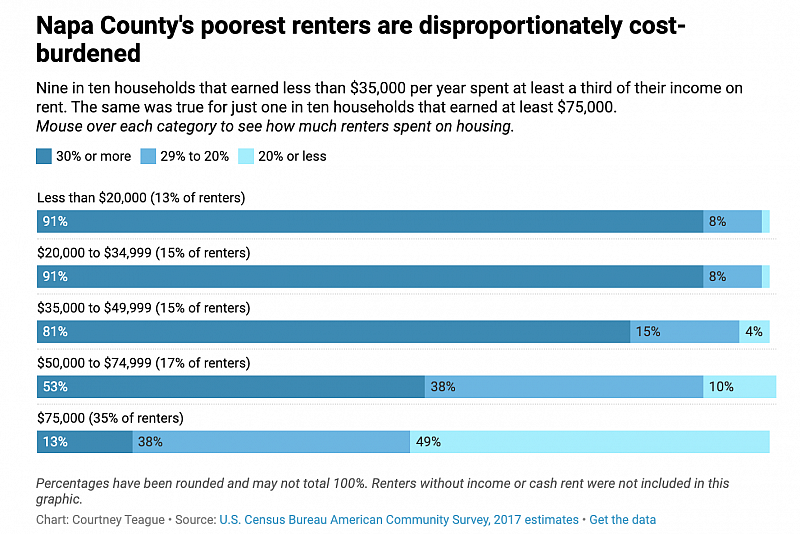

Nearly four in 10 Napa Valley residents rent and half of renters are housing-cost burdened, meaning they spend at least a third of their income on rent, according to 2017 Census estimates. Almost 40 million American families were cost burdened in 2015, according to research from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Nearly a third of Napa County homeowners with a mortgage pay at least $3,000 per month, Census estimates show.

The stress of finding and holding on to housing in the county’s tight market can be detrimental to mental and physical health, say staff of local community nonprofits.

Putting home above health

Heads of households are particularly prone to housing-related stress, said Jenny Ocon, executive director of UpValley Family Centers. When so much of a family’s income goes toward housing, she said it can keep them from meeting other basic needs.

Low-income people who struggle to pay rent or utilities were less likely to have a regular source of medical care, and were more likely to postpone treatment and rely on hospital emergency rooms, according to a 2005 study by Joseph Harkness and Sandra J. Newman.

For Palafox, the stress she faces is so intense that she said she’d like to return to therapy, which she first started after her husband’s death. She stopped going after her counselor passed away, too, and now she says it’s a matter of finding the money and time to take off work.

Palafox expects her financial predicament to worsen later this year, when her monthly rent will increase by $100.

She’s considered moving to a place with a lower cost of living, but Palafox said she stays in St. Helena because of her kids — it’s a peaceful, safe community with good schools.

“With the little bit of work that I have, it’s really hard,” she said.

Patients at OLE Health, Napa County’s second-largest health care provider that serves many low-income and immigrant patients, often cite housing as a concern, said Jamie Bongiovi, OLE Health’s behavioral health director.

Stress about paying rent or a mortgage can turn into hopelessness, which can spiral into depression. It causes a chemical change in the body that can worsen chronic conditions such as pain, diabetes, heart disease and fibromyalgia, Bongiovi said.

Housing and health are so closely connected that Bongiovi said OLE Health asks all incoming patients about their current housing situation and whether they are worried about losing their housing.

It’s not unusual for staff to hear stories like that of one patient, a single parent working full-time and overtime, who lost their housing for a reason that they had no control over, Bongiovi said. The parent slept on friends’ couches while their kids stayed elsewhere, and eventually became very depressed and had thoughts of not wanting to live.

Others with mental health struggles may avoid seeking help altogether, said therapist Rosa Olmos, who has worked throughout the county. That’s particularly true for Latinos, who tend to come from backgrounds that place a greater stigma on receiving mental health treatment. Latinos may worry about appearing “crazy” or weak, she said.

Latino men tend to be especially afraid of the stigma, though men, generally, are less likely to speak out about their struggles, Olmos said.

“Men are supposed to suck it up,” she said. “You’re not supposed to complain.”

For some patients, timing is the reason they don’t get help. Housing is pricey, wages aren’t increasing and people are just trying to survive, Olmos said. Taking time off work may not be an option.

Olmos said housing has been a source of stress and anxiety for her patients, and it can be one of the major stressors that exacerbate an existing mental illness.

She said she’s known patients who were given a notice to leave their homes during remodeling and slept in their cars. Residents of low-income housing face much anxiety about renewing their housing situation, and others worry about where they will turn if they have to leave their home.

It’s not just adults who face anxiety over the tight housing market, said Olmos, who has provided counseling services to local schools. Kids might worry about losing friends if they have to move somewhere that is cheaper, or not being able to afford soccer lessons or ice cream if their parents are pregnant.

“I’ve seen the shift where families, they’re moving out of the county,” she said.

Making rent: ‘It’s stressful’

Upvalley resident Maria, 27, relies on her parents as an emotional support network when the stress and anxiety over housing get to be too much. The three of them typically work two jobs each to afford the three-bedroom, low-income unit they rent for $1,600 in northern Napa County.

The Register has agreed not to identify Maria’s real name, or places of employment and residency because her family has not disclosed all of its sources of income to its low-income housing provider.

Maria said her family has sought cheaper housing, but couldn’t find anything.

They don’t want to leave their home. It’s safe, Maria said, and it’s the place she’s called home for the past 15 years, since she moved to the Napa Valley from Mexico.

Her family doesn’t spend as much quality time together as they’d like because they work so much, she said.

“It’s stressful because we’re really (close),” Maria said. “We do spend time together, but we are tired from work.”

Stress isn’t the only way that housing costs have affected her family’s well-being.

When her father fell ill with Hepatitis E about a year ago, Maria said the costs weren’t fully covered by the health insurance he purchased through Covered California, the marketplace that allows Californians to buy insurance under the federal Affordable Care Act of 2014.

The local specialist Maria’s dad originally saw was too expensive. Her family was already living paycheck to paycheck.

They found a less expensive doctor at a hospital in Sacramento, but Maria said the costs of visiting her dad for the two or three months he stayed there added up. They cut back on certain groceries, such as meat.

And then there was the rent.

“We can’t say, ‘Oh, can you guys wait this month?’,” Maria said.

Maria and her mother worked extra hours to compensate, she said. They were tired and stressed.

Needy residents have limited options

The Census Bureau estimated that in 2017, the median cost of rent for Napa County households was $1,541.

Napa County’s median home value is $670,000, according to a June 2019 report by real estate website Zillow.com. The city of Napa came in at $660,000, while American Canyon had the most affordable median home value at $548,500. St. Helena’s median home value was the highest at $1.4 million, according to Zillow.

View the graphic below to see how much Napa County renters spent on housing:

In 2015, the average monthly rent in California was $1,240, which was 50 percent higher than the national average of $840 per month, according to a report from the California Legislative Analyst’s Office. The average California home cost $440,000 at that time, which was two-and-a-half times the national average of $180,000.

In Napa County, those looking for subsidized housing have limited options.

Section 8 of the Fair Housing Act of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 established the federal housing voucher program to assist low-income, elderly and disabled renters with finding housing.

Napa County’s Section 8 list, which is maintained by the city of Napa’s Housing Division, has been closed since March 2013.

Napa isn’t alone in this — places throughout the country have Section 8 lists that are closed or have long waitlists, said Elizabeth Kneebone, research director for UC, Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation. One in four people who are eligible for a voucher actually get one, she said.

Napa County’s Section 8 program currently serves 1,125 people and 1,121 are on the waitlist, though the city hopes to reopen the list in the next year or so, depending on Section 8 voucher turnover and federal funding, Housing Manager Lark Ferrell said in an email.

‘Drowning’ to stay in Napa

The neediest renters may spend a higher proportion of their income on housing, according to a 2019 analysis by Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, but housing-related stress can manifest itself in other ways.

Even if someone spends enough money to get the home that they want, they may pass on other expenses, such as healthy food or doctor visits, to afford their mortgage, said Bongiovi of OLE Health. Stress can stem from living in a neighborhood without green spaces or facing a long commute. Not having the means to afford housing in a desired neighborhood that can affect stress too, she said.

That was the case for Napa native Danielle Jones, 40, who left her hometown of Napa for Fairfield after she and her husband realized they could live in a bigger home and save up to $700 per month in housing costs there. Jones, who homeschools her four children, said affording life in Napa on her husband’s salary alone became too much. Jones and her husband, who is also from Napa, pray that they can one day afford to return and buy a home.

“Sometimes I ask myself if I’m crazy,” she said.

When Jones thinks about her hometown, she feels conflicted. She said she’s happy to see it thrive, but “it just seems that it doesn’t necessarily have a place for us.”

Fourth-generation Napa resident Kim Ilsley, 30, who was interviewed weeks before her wedding, said she felt anxiety about how to navigate the next step in her life — she and her partner want kids soon, but don’t want to bring children into a home with roommates or substandard living conditions.

“There’s part of me that so deeply wants to stay in Napa and to be part of the amazing culture and community that we have here. This is my home,” Ilsley said. “But I don’t want to break my back and kill myself financially to live in Napa.”

Even Napa resident Michelle Singh, whose landlord keeps his rents below market rate out of concern for and to retain his tenants, said housing is a struggle. At one point, her husband, a seasonal worker, was in between jobs. Singh became the sole breadwinner and they exhausted their emergency fund.

They rented out their second bedroom to a roommate to bring in extra cash. Singh said sharing the home between four people, including her 2-year-old, was stressful. At one point, she sought counseling to alleviate her stress.

Singh’s family currently has no plans to move and wants to stay in Napa.

It’s a “small community where everyone’s really close and supportive, and they see you,” she said. “It’s nice to be seen not just when you’re at your best … but when you’re struggling too.”

Still, she doesn’t think they’d be able to stay in Napa if they needed to move out. Much of her family’s income goes toward student loans and child care.

That’s also the case for Leslie Mullowney of Napa, a mom of kids aged 2 and 4, who faces about $100,000 in student loans. She and her husband, who is self-employed, pay $1,800 per month in pre-school and child care costs and $3,000 per month for their three-bedroom home.

Her family’s expenses are so great that she’s hesitated to bring herself or her youngest child to the doctor for non-emergency situations at least three times in the past year to avoid a $75 copay.

“We’re drowning,” she said. “It sucks all the time.”

Mullowney recently returned to the workforce after losing her marketing job at a winery as a result of the 2017 North Bay wildfires. At the time, she was on maternity leave after giving birth to her second child.

Mullowney said she developed post-partum depression and was seeing a therapist regularly until she lost her employer’s insurance and switched to a Covered California plan around the time her daughter was 5 months old. She said she’s been on the same medication since and hasn’t been to any therapy sessions.

Mullowney went back to work in part to get better benefits because she’s unhappy with the care she’s received through Covered California. She said she’s already texted her old therapist about the possibility of returning after she’s eligible for insurance through her new job.

The past couple of years have been tough for Mullowney and her husband, she said. They’re considering buying a home, though Mullowney said he wants her to consider moving to a state with a lower cost of living.

“We’re killing ourselves to make it happen,” she said. “Maybe we do have to move. I don’t want to.”

[This story was originally published by Napa Valley Register.]