Doctors weigh in on new Alzheimer’s drug

This story is part three of a larger series led by Darlene Donloe, a 2021 California Fellow, who is researching Alzheimer’s disproportionate impact on the Black community.

Her other stories include:

Part 1: Silent killer infiltrates the Black community

Part 2: Blacks with Alzheimer’s face obstacles to care

Part 4: Alzheimer’s caregivers share stories of stress, heartache

LOS ANGELES — When the Federal Drug Administration announced June 7 that it had given conditional approval of Aducanumab to treat Alzheimer’s disease, it offered new hope to millions of caregivers and patients who welcomed and applauded the decision.

However, some in the medical community, including doctors, scientists and researchers were stunned by the approval and questioned the idea.

Aducanumab is the first new drug approved to treat Alzheimer’s disease in nearly 20 years.

“There is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Jarrod Carrol, who has worked with the Southern California Permanente Medical Group since 2016 at Kaiser Permanente West Los Angeles Medical Center. “The approval of aducanumab was not based on evidence of clinical benefit so I strongly recommend not to use this medication. The risks significantly outweigh the potential benefit.

“Most concerning is the risk of brain bleeds and brain swelling that was experienced by a large group of participants in the research trials for aducanumab,” Carrol said.

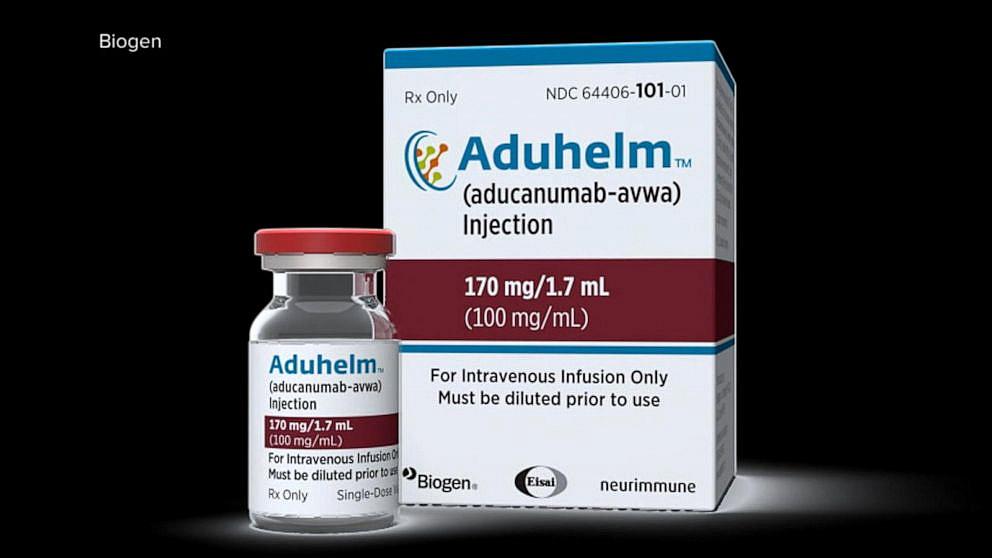

The controversial drug, which goes by the name Aduhelm, is a monthly injection priced at $56,000 annually.

“This drug is very complex,” said Emnet Gammada, Ph.D., a clinical geropsychology fellow at the UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior. “We do not have scientific evidence for this drug right now. A panel of scientists who advises the FDA said they voted against the approval.

“The evidence is insufficient. There is uncertainty in the data,” Gammada added. “We don’t see any improvement in cognition. We’re not seeing cognition getting better. A cure would be if your loved one could get back to who they were.”

Gammada said the drug “also has a significant adverse effect.”

“About 35% of patients on trials had brain swelling and brain bleeds,” she said. “That’s a large chunk of people having this effect. We want to have hope, but we don’t want it from assertions.”

When it was first announced, Aduhelm, a monoclonal antibody that targets a protein in the brain that clumps into plaques in people with Alzheimer’s, was touted as a major medical breakthrough. Almost immediately, though, there was a debate over the efficacy of the new drug.

In fact, both the highly respected Cleveland Clinic and the Mount Sinai Health System in New York said, for now, they would not administer the drug, Aduhelm to patients.

The FDA’s own advisory board voted against the approval. Still, the FDA moved ahead siding with families and doctors who are desperate for help.

The advisory committee reportedly has doubts, saying even if Aduhelm can slow the cognitive decline in some patients, it doesn’t outweigh the risks of taking the drug.

The FDA approved it on the condition that Biogen conducts a new clinical trial while the drug is in use. The FDA could rescind its approval if the new clinical trial fails.

It has been reported that several insurance companies also do not plan to cover the cost of the drug for now.

In a stunning turn of events, the FDA has asked for an independent investigation into its own approval of the drug.

Biogen, the maker of Aduhelm, is standing by the drug.

In a statement sent to The Wave, it stated: “Aduhelm is the first and only treatment to address a defining pathology of Alzheimer’s disease, the abnormal accumulation of amyloid-beta plaques. Amyloid-beta is a protein that accumulates in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s.”

The statement went on to say that, “The efficacy of Aduhelm was evaluated in two phase 3 clinical trials —Emerge and Engage — in patients with early symptomatic stages of Alzheimer’s disease (mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia) with confirmed presence of amyloid pathology and in a Phase 1b study, Prime. In these studies, Aduhelm consistently showed a dose- and time-dependent effect on the lowering of amyloid-beta plaques. The FDA granted accelerated approval based on substantial data reflecting an observed reduction of this amyloid-beta plaque, which is a biomarker that is reasonably likely to predict a clinical outcome.”

Biogen added, “As FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock recently reaffirmed, the approval of Aduhelm was based on very solid grounds and the right thing to do for patients. Biogen continues to stand 100% behind Aduhelm and the clinical data that supported approval. If any patient is denied access to care, we encourage them to contact us for help as we remain committed to supporting access to Aduhelm for all appropriate patients.’’

Biogen said Aduhelm is the first drug to reduce the plaque in the brain and not just treat symptoms of the disease.

Ahuhelm is said to be the first drug to attack how Alzheimer’s works. It reportedly slows the progression of the disease and targets a protein that is a biomarker for Alzheimer’s.

Asked why there was not a significant number of Blacks included in its clinical trial for Aduhelm, Biogen said in a statement, “The Aduhelm phase 3 trials recruited over 3,200 patients. As an organization, we are fully committed to health equity and diversity in our trials and recognize that the Black/African American and Latinx population in our Emerge and Engage trials is not representative of the community.

“Scientific literature points to some common barriers that are often associated with lower enrollment in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials, and Biogen is committed to increasing the representation of underrepresented and underserved populations in our future studies. This initiative is a key priority for the company and a critical element of our latest Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion strategy announced in 2020.”

“I think that it’s a great feat that scientists were able to get it approved,” said Dr. Cerise Elliott of the National Institute on Aging. “I think it’s a great example of how clinical trials have appropriate representation so we have a clear understanding of how drugs work in particular populations. It’s a great achievement. We’ll be working strong.

“The pipeline to come up with a better drug is strong,” she added. “We really want to work on having appropriate representation. We need to work hard on practical and proactive approaches. We also need an engaged diverse pool of volunteers. This is the time we need to examine why Alzheimer’s is so prevalent for African Americans.”

“There is controversy about its approval,” said Dr. Keith Vossel, center director for the Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research and professor of neurology at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine. “When it comes to clinical trials, we haven’t enrolled diverse populations as we should. It’s an ongoing problem.

“My goal is to make our research and clinical programs more accessible and build trust with communities of color. There is much work to be done there.”

Alzheimer’s afflicts 6 million Americans and that number is predicted to grow to nearly 8 million in the next 20 years, according to a 2009 report by the Alzheimer’s Association. Because the disease has no cure, medical researchers continue to focus on preventing or delaying the disease.

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism California Fellowship. The upcoming final installment of the Alzheimer’s series will focus on the important role of caregivers for Alzheimer’s patients.

[This article was originally published by Los Angeles Wave].