In radon's ground zero, leaders have failed to protect Ohioans from deadly gas for decades

The article was originally published in The Columbus Dispatch with support from our 2025 National Fellowship and the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Radon exposure caused Buddy Busch's wife's cancer. Buddy Busch wants Ohioans to know about the risks of radon exposure.

VIEW GALLERY

A surreal silence gripped Patti Busch and her husband, Buddy, as they made the short drive from a Newark urgent care to the Licking Memorial Hospital emergency room.

A day earlier, Patti thought she fractured a rib while leaning over her grandson's Pack 'n Play and when doctors took a look, they found a tumor the size of an orange growing on her left lung. Driving to the hospital for more tests, Buddy said nothing pierced the tense quiet in the car except for Patti’s fears about what she might miss.

She might not see her only son, Zachary, graduate from college. She may not get to watch him stand at the altar to marry the love of his life. And she may never meet another grandchild.

“All those things, they just kind of pile up,” Buddy said. “They’re memories of things you’re going to miss.”

An oncologist told Patti she was right to worry: she had stage 4 lung cancer. It was July 2016 and the doctor estimated she had nine to 18 months to live.

Patti and Buddy cried on and off for days. After the initial shock wore off, Buddy said his wife couldn’t stop wondering what caused the tumor as neither of them smoked.'

Instead, the problem was all around them — an invisible killer they suspected but didn’t discover until it was too late.

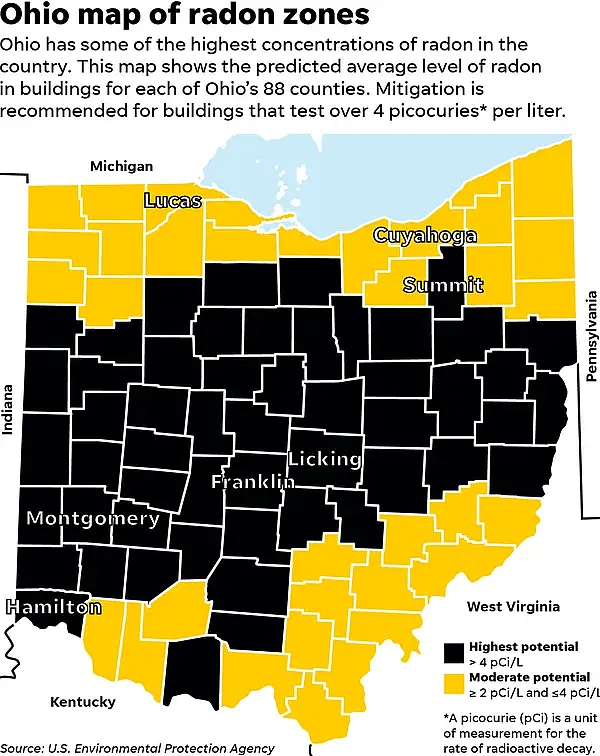

Like Patti, millions of Ohioans don't know they're inhaling air poisoned by radon, a naturally occurring, toxic gas created by decaying radium and uranium in the soil beneath an estimated 50% of Ohio homes, according to the Ohio Department of Health.

The odorless, colorless gas can seep into any building through basements and concrete slabs and many Ohioans only learn of radon if they buy a house. Radon causes an estimated 2,559 cases of lung cancer in Ohio a year and kills 21,000 Americans annually, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Buildings in each of Ohio’s 88 counties have tested positive for dangerous levels of the radioactive gas. And homes in Newark's 43055 ZIP code have the highest concentration of radon in the nation, a 2025 Harvard University study found.

One of those Newark homes was Patti and Buddy's house on Deer Run Road.

The couple didn't know they were living in the nation's ground zero for radon, Buddy said, and never imagined it would cut Patti's life short.

No level of radon is safe. But when Patti's doctor suggested she test her home, the results were more than six times the Environmental Protection Agency's recommended action level of 4 picocuries per liter.

Patti was breathing in air that was so toxic it was the equivalent of smoking at least 40 cigarettes per day or getting 1,000 chest X-rays a year, according to a 1990 CDC toxicological profile of radon. While no medical test can link radon to a person’s specific cancer, the CDC has deemed it the leading cause of lung cancer among nonsmokers.

Though it was too late to undo Patti's diagnosis, the couple still installed a radon mitigation system, which typically costs between $1,000 and $2,500.

Patti decided to focus more on what she could control, and Buddy said that meant spending some of the time she had left raising awareness about radon. She hoped her advocacy meant someone else wouldn’t suffer the same fate she faced.

“She just kept saying: ‘God’s not finished with me yet,’” Buddy said. “She knew that her life wasn’t over.”

Instead of the months doctors suggested Patti had left, she lived for six and a half more years. She got to see her son graduate and get married and she held another grandchild before she died at age 71 on Feb. 10, 2023.

Buddy Busch adjusts the decorations by the headstone of Patricia Adele Busch at the Wilson Cemetery on Sept. 11 in Newark. Patti died of radon-induced lung cancer in 2023.

Samantha Madar/Columbus Dispatch

Buddy still lives in Newark, though he has since moved out of the couple's old home where he watched Patti teach their grandkids to bake bread and chocolate chip cookies. He also married a woman who, like him, lost her spouse to cancer.

Whenever the seasons change, Buddy visits Patti’s gravesite on a small hillside in Licking County. He decorates her grave to reflect the time of year and in mid-September, pumpkins and leaf decor already adorned Patti’s headstone.

The decorations are a small gesture that Buddy said his former florist wife would appreciate. But, Patti is still waiting for what she really wanted at the end of her life.

“Require radon testing to save somebody’s life,” Buddy said. “You could save a lot of pain and agony and misery for a lot of people.”

‘Are you kidding me?’: How Ohio falls short on radon

While central Ohio is a national epicenter of radon, inaction and a vacuum of awareness have left Ohioans like Patti to face an early, preventable demise.

An eight-month Dispatch investigation found that, despite knowing of radon's threat since the 1980s, federal, state and local policymakers have for decades failed to protect Ohioans from the invisible killer lurking in their homes. Interviews with cancer survivors, doctors, scientists, researchers and lawyers, along with a review of thousands of records spanning nearly 40 years, found the failures have left Ohioans at higher risk of what the CDC calls the deadliest cancer of all.

The Dispatch's own on-the-ground testing found dangerous levels of radon in both new and old homes across central Ohio — showing the gas doesn't discriminate when it comes to its victims.

As states around the country have required radon testing in schools, daycares and public spaces or helped to fund mitigation in houses and rentals, The Dispatch found Ohio has failed to follow suit.

The Ohio Department of Health offers free mail-order tests, but only a fraction of Ohioans have taken advantage of the program.

From 2016 through Oct. 3, 2025, the state had given away 71,434 tests — equal to 1.4% of the roughly 4.9 million households in Ohio. The state didn't track the number of tests it gave away before 2016, a spokesman said.

Although half of Ohio homes may have high levels of radon, only 67,668 had mitigation systems as of 2021, according to the state's cancer control plan.

At least eight other states offer funding to mitigate radon in homes and schools, according to the Environmental Law Institute. Columbus previously offered grants specifically to help mitigate radon in low-income households, but federal funding for that program was scrapped.

Even with the state’s free tests, Ohio is the fourth worst state in the nation for testing when taking into account its high levels of radon and the amount of testing being done, according to a 2022 American Lung Association study. Just South Dakota, Montana and North Dakota are in worse shape than Ohio.

And The Dispatch found Ohio's most vulnerable residents may be most at risk — including children and those who rely on public housing.

Records obtained by The Dispatch show some housing authorities around Ohio may not test for radon at all. Others may not notify residents of dangerously high results and have waited months or years to mitigate.

At least 13 states require child care centers to test for radon and 11 states must test in schools, including neighboring West Virginia, according to the Environmental Law Institute. Ohio is not one of them.

In March, Ohio lawmakers denied a $15 million request to help test for radon in schools. Just a year earlier, legislators approved $432,652 to abate radon, asbestos and other toxic substances in state buildings where they work.

Requiring more testing and mitigation would save lives, said Stuart Lieberman, a New Jersey-based environmental attorney who attended Capital University Law School in Columbus.

“Are you kidding me?” Lieberman said. “You don’t want to mess around with this. (Ohio) should follow the lead of other states that already require it.”

The Ohio Department of Health raises radon awareness by educating Realtors and through paid social media and digital audio advertisements in a campaign each January. Last year’s push resulted in 11 million “impressions,” 33,000 clicks to the state’s radon webpage, 673 reactions and 181 shares, according to the department.

Ohio Department of Health Director Dr. Bruce Vanderhoff declined to be interviewed for this story. In a prepared statement, he encouraged Ohioans to test and mitigate for radon.

The radon awareness campaign is one of 175 programs the department runs and "one we take very seriously," a spokesman said. But, the Ohio Department of Health has failed to publish radon test results it collects from companies since 2020.

The department refused part of a Dispatch records request for ZIP code-level testing data, claiming state law doesn't require it to produce whole databases and because outdated software prevents the agency from de-identifying the information. The department previously contracted with the University of Toledo to sort testing data, but that funding was eliminated in 2020, a spokesman said.

Officials later told The Dispatch the department would again publish ZIP code-level radon data and county maps on its website, but would not say when.

As radon has been linked to more illnesses, such as leukemia, dementia, strokes and heart attacks, the White House has proposed scrapping funding for radon programs across the country in 2026. If approved, Ohio could lose roughly 46% of the nearly $750,000 it spent on awareness, testing and licensing in fiscal year 2025.

A map of radon's estimated levels in each of Ohio's 88 counties. The Environmental Protection Agency recommends remediation if a test result returns a reading of 4 picocuries per liter or more.

Jason Bredehoeft

At the same time, the EPA’s National Radon Action Plan ends in December, and while an EPA spokesperson said discussions are underway about a future plan, it's unclear whether one will come to fruition.

The plan aimed to increase the number of radon mitigation systems in homes nationwide from 1.6 million in 2015 to 8 million by the end of 2025. As of August, 6.8 million systems had been installed, an EPA spokesperson said.

The fight for support is nothing new to those pushing for change on radon, The Dispatch found.

When radon was first revealed as a widespread threat in 1986, the Government Accountability Office called it a “public health emergency.” The GAO suggested the Federal Emergency Management Agency — which is tasked with handling the aftermath of hurricanes, tornadoes and floods — could manage radon.

Instead of FEMA, the Indoor Radon Abatement Act signed into law by President Ronald Regan in 1988 mandated the EPA create guidelines for testing and reducing radon. But experts and advocates told The Dispatch the law didn’t go far enough and failed to give the EPA authority to require testing or mitigation.

Since then, federal and state agencies have played a game of hot potato with radon, said Matthew Bozigar, an environmental epidemiologist studying radon at Oregon State University.

“It remains this invisible, odorless, tasteless thing that you have no idea is in your home,” Bozigar said. “So it is very easy just to write that off.”

The fallout has rippled across the state, leaving Ohioans to suffer from life-altering illnesses and others to carry the pain of losing loved ones.

Lung cancer survivors and families told The Dispatch they felt outraged they may have been able to prevent their disease if they had known about radon. Most had never once taken a puff of a cigarette and were baffled by a diagnosis they thought only smokers could get.

Together their stories represent the growing toll of radon in a state that, compared to others, has done little to stem its damage.

“What’s the value of a life?” Lieberman said. “You can’t overstate the importance of this. The Ohio legislature needs to take a very close look at it.”

Dispatch testing reveals widespread radon in central Ohio

Molly Fox spent hours playing with blocks and building forts in the basement of the Bexley home she and her husband bought from her parents.

Fox, 32, hopes to turn the unfinished basement into a new space where she can spend time with her husband and their 7-month-old daughter.

In September, though, Fox’s basement tested at 14.7 picocuries per liter for radon as part of The Dispatch's testing program. At three-times the EPA's action level, radon may have creeped up to the first floor of her home, testers told The Dispatch.

“Even with the high results, I feel better than I did because I have more information,” Fox said. “We do our laundry down there, but I’m trying to spend as little time as possible down there.”

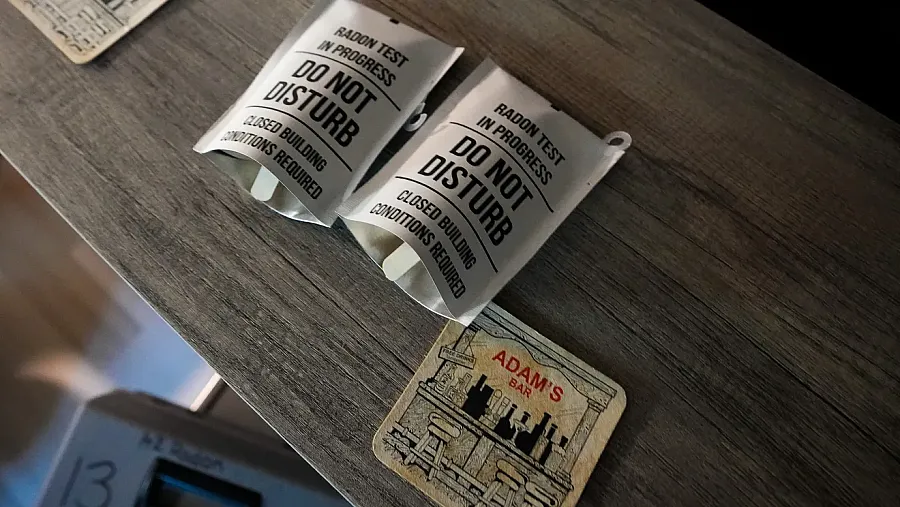

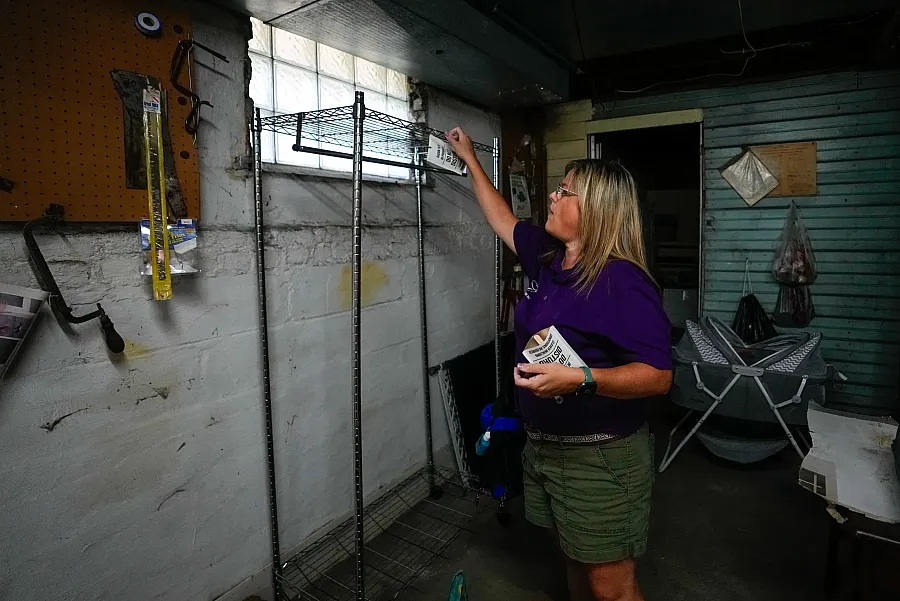

What does radon testing look like? See Ohio residents' experience. An A-Z Solutions technician tests for radon in Columbus area homes, searching for the invisible gas tied to health risks.

VIEW GALLERY

Fox’s home was one of 68 households The Dispatch tested after the Ohio Department of Health repeatedly denied requests for decades of data.

Testing found radon near or above dangerous levels throughout the region, including in some of the wealthiest neighborhoods, in public housing and in rural areas.

With environmental company A-Z Solutions, The Dispatch deployed 128 tests and several continuous radon monitors in the 68 homes during one wave of testing in September and another in early October in Franklin, Delaware and Licking counties. To ensure accurate results, two standard charcoal tests or a test and a continuous monitor were left in most homes.

Fifty-four homes, or 79.4% of those examined, tested positive for radon above the EPA's remediation threshold of 4 picocuries per liter. The Dispatch's results were higher than the 50% of homes the Ohio Department of Health reports test high each year.

The highest result of 58.7 picocuries per liter came from a home in Hebron. A continuous monitor left at the same home found radon there at one point reached 70 picocuries per liter.

Jessica Karns, from A-Z Solutions, sets up radon testing equipment at Molly Fox's home in Bexley on Sept. 9. Fox's home, which she and her husband bought from her parents, tested high for radon.

Samantha Madar/Columbus Dispatch

Two Columbus homes, one on the Near East Side and another on the Northwest Side, each registered results of 0.5 picocuries per liter, the lowest level The Dispatch found locally.

To continue testing, The Dispatch has partnered with the Columbus Metropolitan Library to launch a borrowing program for continuous radon monitors.

The monitors will become available to library card holders beginning Dec. 11 at a 6 p.m. launch event at the Reynoldsburg branch at 1402 Brice Road. After the initial launch, a monitor will be available to borrow at each of the library system's 23 branches.

Borrowers can scan a QR code on the device to voluntarily report results to The Dispatch or by visiting Dispatch.com/radon.

Any result, high or low, should feel empowering to homeowners and tenants, Bozigar said. More information allows them to take action, he said, even if it makes some worry about what they've been breathing.

The basement in Molly Fox's Bexley home tested at 14.7 picocuries per liter for radon as part of The Dispatch's testing program. That's three-times the EPA's action level for radon.

Samantha Madar/Columbus Dispatch

“If you could go back in time and prevent some nasty health issue, would you? I’m sure everyone would say yes,” Bozigar said. “But I think there's a part of the human psyche that has a hard time dealing with: 'have I been at risk this entire time?’"

Fox is focused on moving forward instead of looking back.

She and her husband plan to mitigate their home for radon this winter. They'll have to save for a system, but they don't want to put it off now that they know it's a problem.

"There's nothing I can do now to go back and change any time I spent down there," she said. "If I obsess over it, I'll probably go nuts, so I'm trying to focus on what we can change now."

'Why us?': Is Ohio ignoring its radon problem?

Buddy Busch had only heard "inklings" about radon when he and and his late wife, Patti, moved to Newark in 2008 so he could lead a religious nonprofit serving people with disabilities.

Many Ohioans learn of radon when buying a home if a Realtor or inspector recommends testing. But with little awareness and no suggestion they test, Buddy said the couple didn't really consider it.

"There was always an underlying feeling of 'why us?'" Buddy said. "Because I took a job in Ohio and moved us here, I always felt like if I hadn't taken that job this wouldn't have happened."

Ohio is one of at least 20 states that require home sellers disclose to buyers known radon due to previous testing, said Jane Malone, national policy director for the Indoor Environments Association, a nonprofit that advocates for environmental hazard abatement.

While Ohio has required disclosure since 1993, no such law exists for renters and if previous homeowners never performed a test, then homebuyers like Buddy and Patti may never find out.

Ohio could follow the lead of 12 other states, including Illinois and Colorado, by requiring information on radon in general be provided to homebuyers. Such policies, which Ohio does not have in place, can double awareness of radon among those in the market for a home, research shows.

Colorado also allows renters to break their lease if an apartment tests high for radon and the landlord refuses to mitigate, a 2023 state law shows.

Among Ohio's other radon laws is one that requires state licensing of professionals and another that mandates the governor convene an advisory council on radiation. One of the only pieces of radon-related legislation to become law in recent years established January as Ohio's radon awareness month.

Annie Cacciato, a victim of lung cancer who Patti befriended, is credited with pushing lawmakers to pass the awareness month bill. The first one was in 2022, less than two months after Caciatto died Nov. 8, 2021.

At the local level, a few municipalities such as Powell, Pickerington and Dublin have passed ordinances requiring radon mitigation in all new buildings. None of the state’s most populated cities of Columbus, Cincinnati or Cleveland have similar laws.

If Ohio’s cities wanted to require more in the way of radon, they could take a cue from municipalities around the country, Malone said.

In 2023, Montgomery County, Maryland, began requiring testing and notification of radon levels and mitigation in all rental housing. The county also mandates testing during home sales, according to its Department of Environmental Protection.

“There’s a perception that radon is only an issue in some parts of the country or even some states," Malone said. "That’s a misperception."

Better than anyone, Jackie Nixon knows how a lack of radon laws can change someone's life.

Nixon believes her lung cancer was caused by radon lurking inside her Pennsylvania condominium. When doctors first found a tumor on the outside of her left lung in 2015, she immediately wanted to sue.

But, four attorneys told her the state she lived in didn’t have a law making building owners test or mitigate. There was nothing she could do.

Nixon, president of the nonprofit Citizens for Radioactive Radon Reduction, fought off a second occurrence of lung cancer three years after her first diagnosis.

Now, she recommends people get their homes checked and provide their radon test results to their doctors so they can add it to their medical file. She doesn’t understand why more isn't being done to raise awareness decades after the gas' threat became widely known.

“We have to solve that problem,” Nixon said. “You’re going to fix people and then you’re going to send them back into high, high levels of radon.”

Three years after a leukemia diagnosis, Graham runs free. Could radon be to blame? From battling leukemia to dodging tackles, 7-year-old Graham Smith shows grit and joy at football practice. Could radon have played a role in diagnosis?

‘This isn’t happening by chance': Radon linked to leukemia

Graham Smith chopped his feet up and down, curly mullet bouncing as he looked at his football coach during practice on a summer evening in Pickerington.

The coach handed Smith the ball and the 7-year-old bobbed and weaved, trying to evade two of his teammates who tackled him into a pile on the grass.

Just three years ago, Graham couldn’t even hold himself up without falling on a scale in the emergency department at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, let alone play football.

At age 4, Graham was diagnosed with Precursor B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia on Sept. 14, 2022.

Research, including Bozigar’s 2024 study at Oregon State, has linked childhood leukemia to radon exposure. And, though it’s not possible to pinpoint the cause of Graham’s leukemia, his mom Nicole Smith couldn’t help but wonder whether radon or another environmental hazard might be the culprit.

“It crossed my mind multiple times,” she said. “I don’t think you can ever end up with a cancer diagnosis and not wonder where it came from.”

Smith's worries about radon kept rising to the top of her mind and she repeatedly asked her husband if he thought it could be the cause.

The family was living in a Hilliard condominium with a radon mitigation system in the crawl space. But they discovered after Graham's diagnosis that the system’s fan was broken and may not have been sucking radon out of the home at all. They’ve since moved to Pickerington.

Bozigar’s 18-year study examined the levels of radon in 700 counties in 14 states. The research found a connection between Leukemia and radon, even in areas where radon levels were lower than what the EPA recommends for mitigation.

Graham Smith takes a break during football practice at Pickerington athletic fields. At age 4, Graham was diagnosed with leukemia, which research has linked to radon exposure.

Samantha Madar/Columbus Dispatch

When looking for a cause of childhood leukemia, Bozigar said radon was the first thing he thought of since, like Ohio, Oregon has high levels of the gas.

“This isn’t happening by chance, it’s not happening at random,” he said. “There’s some reason behind it.”

While five of every 100,000 kids develop leukemia a year, Smith never thought her own son would suffer from it. She still remembers feeling overwhelmed with fear when the doctor said the word “cancer” for the first time.

But Graham was one of the lucky ones.

He was declared cancer free a year ago and rang the bell at Nationwide Children’s Hospital — a rite of passage for kids who beat cancer there.

Still, Smith will never forget the bright purple bruises that dotted her child’s body or Graham hugging his knees to his chest as a long, thin needle full of chemotherapy punctured his little back.

“I try my hardest not to take life so seriously because I do recognize just how fleeting this time is with my kids,” she said.

‘Let’s not pick': How radon became an overlooked public health crisis

Before Kyle Hoylman could do something to protect his parents from the radon infiltrating his childhood home, his dad was gone.

Hoylman, CEO of Protect Environmental in Columbus and Louisville, brought a radon test home to Chillicothe for the holidays in 2007.

After the results came back at 35 picocuries per liter, he insisted his parents mitigate their home. But before that happened, Hoylman's dad, George, called him with devastating news. He had late stage lung cancer.

Six months later, Hoylman's dad was gone and so too were their Sunday family breakfasts at Bob Evans and morning cups of coffee on the front porch.

Kyle Hoylman looks at a radon mitigation system his company Protect Environmental installed in a home in Louisville, Kentucky. Hoylman, CEO of Protect Environmental, lost his father to lung cancer he believes was caused by radon.

Matt Stone/Courier Journal

Radon remains “the most significant environmental contaminant out there,” Hoylman said. Yet, 16 years after his father died, he said it’s still not treated like better known threats, such as carbon monoxide or fires.

Carbon monoxide unintentionally kills around 400 people a year nationwide, according to the CDC. Unlike continuous radon monitors, carbon monoxide detectors have become a staple of many American homes.

Fires kill 3,670 people in the U.S. annually, which is also far less than radon, according to the National Fire Protection Association. When it comes to fires though, Hoylman said “you can’t construct a new building anywhere in our country without a fire suppression system.”

“Let’s not pick. Let’s just put it in the code and build it,” he said. “It still baffles me.”

The building code isn't the only area that's lacking when it comes to radon.

Doctors in training receive “limited education” on the dangers of environmental radiation, according to research published in the medical journal Radiology in 2021. Just 20% of medical students are required to complete a radiology clerkship.

The risks of radon exposure have also been consistently "understated in most professional healthcare curriculums," according to research published in the Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing.

As an oncologist at Zangmeister Cancer Center in Columbus, Dr. Sam Mikhail was embarrassed he first learned of the dangers of radon when he bought a Columbus area home in 2013.

“For the physicians themselves, there is very little education about radon,” he said. “It is not being taught in medical schools, not in oncology programs.”

At his Realtor's suggestion, Mikhail tested his home for the gas and when the results came back at 11 picocuries per liter he had a mitigation system installed. But Mikhail worries that if he, as a cancer doctor, received no radon education, then physicians who are not specialists might also be unaware of the threat it poses.

While smoking is widely known to cause lung cancer, radon can make a deadly diagnosis even more likely in people who previously smoked, such as Hoylman's father. Radon exposure puts both current and former smokers at 25-times greater risk of lung cancer than someone who hasn’t smoked, according to the World Health Organization.

Kyle Hoylman holds a picture of his father, who died from lung cancer, outside a home with a radon mitigation system his company installed in Louisville, Kentucky. Hoylman is the CEO of Protect Environmental.

Matt Stone/Courier Journal

But, Hoylman’s dad hadn’t lit a cigarette in more than 20 years by the time he was diagnosed with lung cancer and he didn't even qualify for lung cancer screening.

Only patients aged 50 to 80 who have smoked and have a "20 pack-year history" are eligible for screening, according to the American Cancer Society. Someone who smoked a pack of cigarettes a day for 20 years, for example, would qualify as would someone who smoked two packs a day for 10 years.

Such screening parameters must be updated to catch more cases of lung cancer, said Dr. David Carbone, head of thoracic oncology and chair of lung cancer research at Ohio State University's James Cancer Center.

Overhauling guidelines has proven difficult though as people have long “discriminated against” lung cancer because of its link to smoking, Carbone said. Until a few years ago, the American Academy of Family Practice didn’t even recommend screening for former smokers.

No other cancer faces such strict screening rules, Carbone said.

“They have made it very restrictive to even the highest-risk patients,” Carbone said. “The fact is that most lung cancers are diagnosed in people who aren’t eligible for screening.”

‘I just pray': How changing minds may be harder than changing laws

By now, Chasity Harney has almost lost count.

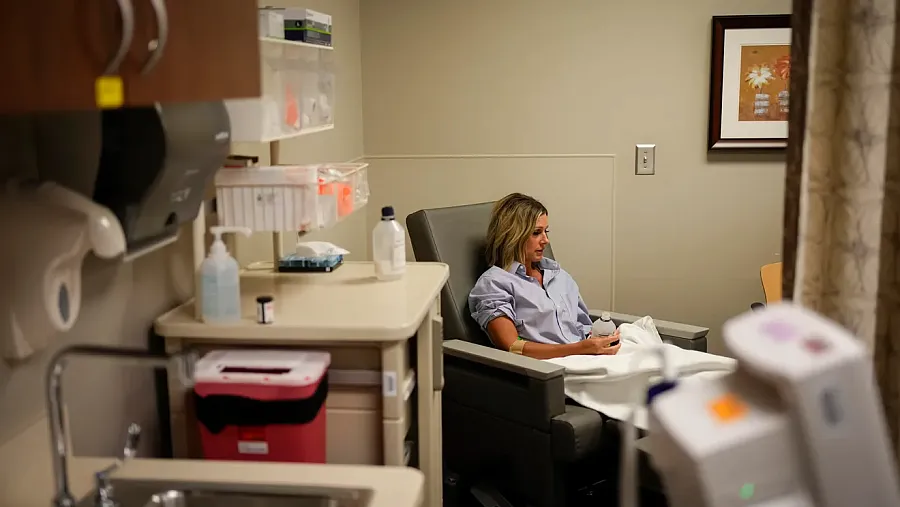

Every eight to 12 weeks, the mother of three makes a two-hour drive to Ohio State’s cancer hospital where she forces herself to choke down two bottles of contrast dye for another CT scan.

At an August checkup, Harney thought she was on CT scan number 55 or so. And that doesn’t include the PET scans and MRIs she’s had in between.

Harney was diagnosed with stage 3 lung cancer at age 40. Now 48, she laid down on the sterile, off-white platform of the CT scanner during her August appointment and the machine began to whir around her.

But as she laid there, she wasn’t thinking about her cancer or how many scans she’s had. Instead, she was thinking about everything she could lose.

What a radiology scan looks like for a cancer survivor who believes radon may be to blame. Lung cancer survivor Chasity Harney undergoes a routine radiology scan at Ohio State and reflects on possible radon exposure.

“Every time I'm in that machine, I just pray," Harney said. "I never thought I’d begin growing old with my husband, watch my kids grow up or meet my first grandbaby.”

A once healthy never-smoker and former grade school teacher, Harney ran five miles the day before she was diagnosed with lung cancer Oct. 9, 2018.

Her home, just south of the Ohio River in Northern Kentucky, tested high for radon at 8 picocuries per liter after her cancer first appeared.

After her diagnosis, Harney said people assumed she smoked. She could feel their judgment and constantly defended herself.

Many nonsmokers like Harney find the smoking question annoying or insulting, said Carbone, who is Harney’s oncologist.

The stigma, Carbone said, has created a type of nihilism and lack of understanding about lung cancer that other forms of cancer simply don’t face. In turn, it's led to a lack of research and funding for lung cancer.

Overcoming lung cancer's stigma has been the most challenging part of raising radon awareness, said Heidi Nafman-Onda, a cancer survivor and founder of the lung cancer nonprofit White Ribbon Project.

“People who get lung cancer, whether they smoked or not, are feeling shame and blame and they don't speak out,” she said.

The stigma couldn’t keep Harney silent though.

One day, Harney’s son brought home an informational lung cancer pamphlet from his fifth-grade class. Packed between the pages of the booklet was information on how smoking causes lung cancer, but there wasn’t a single mention of radon.

“Are you serious?" Harney recalled saying. "Now he’s thinking: my mom did this to herself."

Harney wrote a letter to her son's teacher and another to the maker of the pamphlet the next day to insist radon information be added.

In the years since her diagnosis, Harney has leaned on her family and her religion to endure multiple surgeries, including one where most of her left lung was removed. She believes spreading awareness is one of the reasons she’s still alive, despite facing a late-stage disease that has a 5% to 20% five-year survival rate, according to the American Lung Association.

While Harney is starting to lose track of all the doctors visits and scans, she hasn’t lost count of the years her cancer threatened to take from her.

Chasity Harney, lung cancer she believes was caused by radon, has Morgan Webb add a tally mark to an existing tattoo at House of Faces tattoo in Elanger, Ky., on Oct. 12, 2025. Harney’s tattoo represents the number of years she’s survived since her cancer diagnosis in 2018.

Albert Cesare/The Enquirer

Around the anniversary of her diagnosis each year, Harney schedules an appointment at a local tattoo shop to add a line to a tally on her upper left arm representing the years she’s survived.

Harney's two daughters, her grandson and other family members filled the lone room of a tattoo parlor on Oct. 12 in northern Kentucky. Along with another tally, Harney added a flower to her right arm with the words "for his glory" — a reminder of her faith that has kept her going.

As the tattoo artist began to draw the latest line in her tally, Harney hoped aloud she might one day run out of space for more.

"I feel like I'm keeping score against cancer and I'm in the lead," she said, looking at the fresh ink on her arm. "Now, it’s in God’s hands.”