Rankin, Pennsylvania: Fighting 'the depressed mindset'

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Rich Lord, a participant in the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Charges lodged in North Braddock arrest

Growing up through the cracks: The children at the center of North Braddock's storm

Growing up through the cracks: Policing change brings cops up close with kids in poverty

Current and former Rankin residents remember the past, envision the future

Pittsburgh's neighborhood boosters face changing landscape

Where fighting poverty is a priority

Growing Up Through the Cracks: Mapping Inequality in Allegheny County

A mother moves from McKeesport to Glassport to try to better her family’s chances

Growing up through the cracks: North Braddock: Treasures Amid Ruins

Jaden Weems, left, joins his father James Weems, who was in the process of installing a flag on his home, and Mr. Weems' daughter Miranda Weems, outside of their home on Fifth Ave in Rankin.

In a town kept down by county decisions and indecision, even the most determined families find it hard to rise above stagnation, deprivation, and violence.

The smell of barbecue, the chef's hat on James “Cube” Weems' head, the earnestness on his son Jaden's face as he passes out samples of steaming meat — it all conspires to give a festive feel to Rankin Borough Council, where the mood is sometimes darkened by talk of the creep of coyotes into the overgrown lots of this old mill town.

Mr. Weems, 45, and Jaden, 14, have come with meat, and with a plan: They'll pour the father's entrepreneurial experience and the family's energy into the long-disused concession stand down by the borough's weedy baseball field. It could become Cube's Chop House, Mr. Weems says, passing out a black business card featuring the pitch: “Delivering exactly what your CHOPS want.”

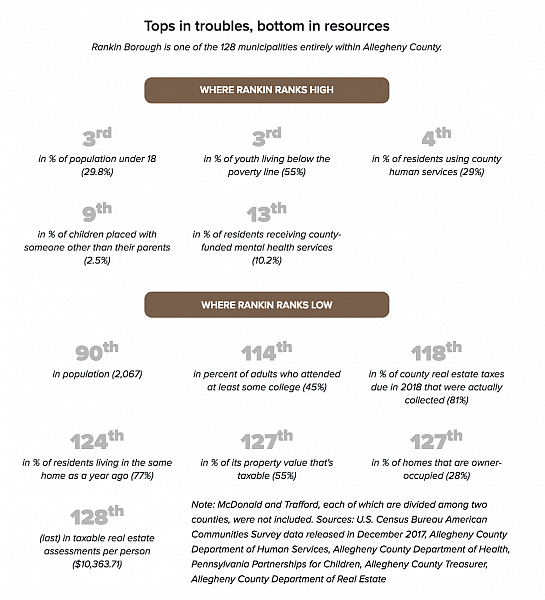

Rankin is starving for business, for revenue, for a reason to believe that, after 30 years as a pocket of poverty, there will be something here for the kids who make up nearly a third of its population.

This half-square-mile borough, nestled between Braddock and Swissvale, looks quaint as you gaze across the Monongahela from The Waterfront’s eastern edge, or look left from the top of the Thunderbolt. But half of Rankin’s kids live in poverty. Most adults haven’t attended a day of college. The town limps along on the county’s leanest tax base.

Jared Todd walks home from school after getting off the bus at Hawkins Village in Rankin. Todd's daily routine includes coming straight home and playing video games, drawing — cartoon characters, hands, flowers, things he sees on YouTube — or writing poems.

Our region’s fragmented governmental structure leaves places like Rankin — and far-flung towns from Arnold in Westmoreland County to Uniontown in Fayette County — with lots of poor kids and without the resources to support and protect them, let alone to lift them up.

This year the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette will take you to a dozen places in which half of the kids are in poverty — a circumstance that hamstrings their futures, and that of the region.

“We know that concentrated child poverty is a multiplier of the negative impacts of poverty, meaning that in concentrated child poverty, there’s more crime, the built environment is horrible, therefore children don’t go out, or if they go out they’re in danger,” says Benard Dreyer, medical director of policies and past president of the American Academy of Pediatrics and a member of the National Academies of Sciences committee on child poverty. “All of their neighbors are under chronic stress so they don’t have any role models of people who are doing better.”

Allegheny County’s actions and inaction have contributed to Rankin’s problems.

Starting in the 1940s, the county pushed low-income housing developments into Rankin — a practice that’s now discredited but hasn’t been reversed. The county provides human services in Rankin and grants for demolitions and roadwork but hasn’t yet redeveloped the vast Carrie Furnace site along the borough’s riverbank.

The result is a feeling of waiting for a ship that may or may not arrive. It affects even those families — like the Weemses — that are not in poverty but are striving to climb the ladder of opportunity.

The concession stand is Mr. Weems’ third swing at making money in the Mon Valley. He takes this shot as his equally entrepreneurial son is inching toward college age and toward decisions about what he'll do and whether he'll live here.

“This is where my family was raised, and I believe that if people understood the benefits of the location and the quietness of Rankin, it would make a serious turn,” Mr. Weems says.

It's hard, though, for a place to shake off decades of rust. There's something invisible that weighs down every effort — a characteristic of his hometown that he hopes his kids won't absorb.

“It's a depressed community. It's the mind, the depressed mindset,” he says. “It's hurtful being from here.”

It may be awhile before Jaden Weems puts his trumpet to his lips and belts out a certain soaring movie theme as the high school band marches down the field. “When I’m going to be a senior is probably when we’re going to play Black Panther,” says the Woodland Hills freshman.

He talks about going to college in Alabama, moving to Los Angeles, launching a just-in-time clothing business, buying a plane or two.

“When you get in the clouds, you see small images,” he says. “That's when my head runs wild.”

Jaden flew a lot in nine years during which his father led the family out of the Mon Valley to Minneapolis, Columbus and Mobile, Ala. They often returned to Rankin, which took on mythical status, thanks to the patriarch’s upbeat take on his hometown.

“Rankin is the capital of the world,” Mr. Weems would tell his two sons and daughter. “It's the best city — the best place ever!”

Five years ago, in response to family health problems, he and his wife, Melinda, told the kids that they’d be leaving their big, bright house in Mobile, forsaking the yard with its orange trees, inground pool, trampoline and running space for Tinsel, their Akita. They’d trade that for an 80-year-old house, in the family for half a century, on a 2,420-square-foot lot in Rankin.

Three days before the move, Tinsel darted into the path of a car and died.

In the weeks that followed the move, neighborhood kids tested Jaden, then 10, Miranda, 7, and their older brother Jalen, 19. “It was rough for them,” Mr. Weems said. “They were like, 'Why are these kids fighting with us?’”

Ethan Zawacki of Chalfant, left, Jaden Weems of Rankin, center, and Sierra Smith of Swissvale, right, joke around before the start of band class at Woodland Hills Junior/Senior High School in Churchill.

The kids’ Alabama drawls and manners stood out.

“When they first heard my voice, they were so confused. They were like, ‘Why do you sound country?’” Jaden says. “They were saying, ‘Why is he saying ‘thank you’ all the time?’ I said, ‘That’s how my parents taught me, to say please and thank you.’”

With a master’s in business administration, experience with GlaxoSmithKline, Target and Praxair, and entrepreneurial chops he’d honed running a cigar shop in Mobile, Mr. Weems took stock of the family’s assets.

He owned a hulking, 117-year-old house in Braddock that he bought in 2002, just after marrying Melinda. With a foundation like “a bomb shelter,” as he puts it, and 3,300 square feet of living space, across the street from the Braddock Carnegie Library, it proved a great place to start a family. “We loved it,” he says.

When they left town, they rented it out. But in 2010, a kitchen fire destroyed much of the interior.

“I cried like a baby when I walked into that house after it was burned up,” Mr. Weems says. He boarded it up, but people ripped off the planks and stole pipes and appliances. Every effort to fix it was reversed by thieves and vandals. “It’s been hell on wheels with that house.”

Insurers declined to cover the house, putting the brakes on his efforts. “If I put any money into it, and it gets burned down, I’m going to lose everything.”

Finally, in September, the county condemned the Braddock house because it was blighted and vacant. With that, after 16 ½ years, the Weems family lost title to its first home.

That was a blow. But by then, they’d already pinned new hopes on “the best place ever.”

Named after grocery wholesaler Thomas Rankin, the borough was chartered in 1892, when it was described in the Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette as “one of the busiest as well as one of the wealthiest of the smaller boroughs.” Rankin was blessed with the Carrie Furnace, the Braddock Wire Works, the Fort Pitt Tannery, the Braddock Glass Co., and a half dozen other industrial concerns.

Fiercely independent, Rankin was the scene in 1911 of a rally at which candidates railed against a “plot” by Pittsburgh Mayor W.A. Magee to annex nearby boroughs.

In 1941, the fledgling Allegheny County Housing Authority opened Hawkins Village, a low-income housing complex named after Col. Richard H. Hawkins, a University of Pittsburgh law professor. Rents averaged $14.25 a month.

By 1953, the borough was no longer “one of the wealthiest” but rather a “grimy industrial community,” per a Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article. Two days before Christmas in 1957, a fire destroyed 40 homes. In reaction, the county moved 470 families to make way for Palisades Plaza and Palisades Manor, two privately owned low-income housing complexes, with a current total of 137 apartments.

Add the 39 Rankin rentals supported by Housing Choice Vouchers — sometimes called Section 8 — and nearly 1 in 3 of the borough’s homes are subsidized. That housing drives Rankin’s child poverty rate.

Some move up. Mr. Weems spent his high school years in “The Village” but now lives in what’s called “Up Rankin.” Over the decades in between, though, the gravity of poverty took its toll throughout the borough.

James Weems of Rankin stands behind the bar in his building on Miller Street in Rankin. He bought the building in hopes of keeping its bar open, but was forced to shut it down because the liquor license was never transferred, leaving him no income, but lots of overdue property taxes.

When Mr. Weems came home from Mobile, there was just one place to go out for drinks in Rankin, and it was sporadically open. Business at Deb’s Place swooned after 2013, when an argument there turned violent, and Darryl Reaves, now 40, fatally shot Tyrone Milton, 50.

Mr. Weems approached the owner about buying the place. For nine months, he worked behind the bar, redecorating and trying to shake the bad vibes from the 2013 tragedy.

“You do a couple of wing nights. You do some crab leg nights. You’ve got some karaoke. You do some drink specials,” he says. Business picked up.

Some patrons, though, didn’t appreciate his style. “I ended up having some issues at the bar, because I just laugh and talk, and people were like, 'Why are you so happy? Why are you laughing? Why are you smiling all the time?’” he recounts. “Because life is good! Life is OK. I'm alive. I'm living.”

Finally, the prior owner sold him the building. But she balked at transferring the liquor license, which Mr. Weems called a violation of their agreement. He sued but didn’t prevail, leaving him with the building — and its back taxes and debts — but not the license he needed to make money from it.

He closed up shop and promptly faced some of the same problems he’d had with the Braddock house. “They broke into [the bar] a few times already, messed my pipes up,” he says. He has since put up boards or bars at most potential entry points.

Then, while he was working for a catering company, inspiration struck: He could convert the bar into a commercial kitchen. He posted a banner above the bar door: Cube’s Chop House.

Now he just has to clean up, build out the kitchen, and find a solution for the near-total lack of parking. “It’s got a lot of potential,” he says, “it just sits in a bad space.”

Packing impoverished families into dense “projects” has been officially out of vogue since 1993, when the federal government started financing the replacement of old public housing with mixed-income communities. Locally, a 1994 consent decree mandated improvements to communities, including Hawkins Village, and efforts to desegregate and disperse subsidized housing.

Still, today Hawkins Village is entirely subsidized housing, in long, low, six-unit buildings, last upgraded in 1994.

Kymarii Howard, 26, is raising four kids — all under the age of 9 — in a Hawkins Village apartment with roaches, loose floor tiles, water-stained plaster and broken cabinets. “I’ve been asking for three years to be transferred to another house,” Ms. Howard says.

Housing authority executive director Frank Aggazio would love to do “a complete modernization” of Hawkins Village, but funding for big rehabs is hard to get. Instead, he plans $2.8 million in repair work on the roofs, windows, chimney, parking lots and sidewalks next year.

Meanwhile, conditions have slowly eroded.

The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development inspected Hawkins Village in December 2017, finding clogged plumbing, damaged door and window locks, inoperable ranges or stoves, and missing or broken hand railings, and estimating that there were 476 health and safety deficiencies in the complex. On a scale in which 60 is a passing grade, HUD gave Hawkins Village a 55.

Mr. Aggazio said that when residents move in, they get a fully intact, safe, clean unit. In a June response to HUD concerns about Hawkins Village, he wrote: “The residents at Hawkins are generally rough on their units.”

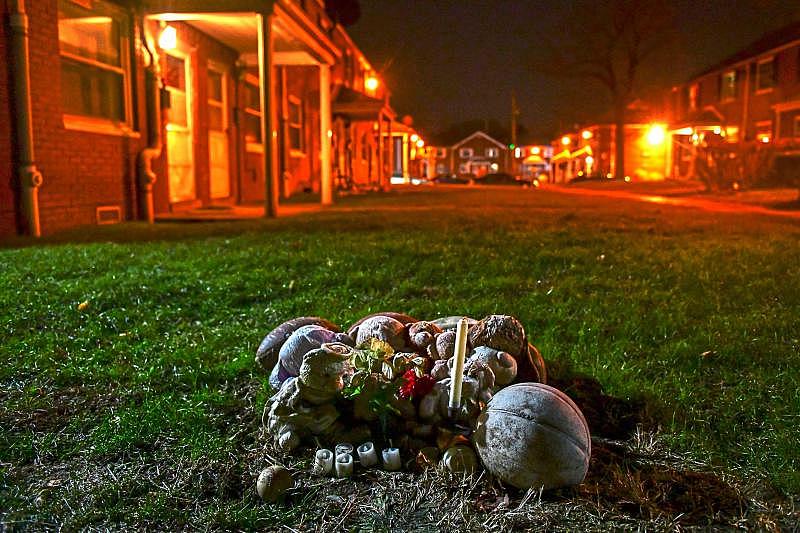

Candles, flowers and toys adorn a makeshift memorial for Kennir Parr of Swissvale at Hawkins Village in Rankin. Kennir, 14, was shot and killed on July 4, 2016. His murder remains unsolved.

“Sometimes I come here in the morning, and there’s all kinds of trash, and I think, ‘How are you living like this?’” says Ava Johnson, who was raised in Hawkins Village, brought up five children there, and led the resident council in the 1980s. She now lives elsewhere in Rankin but works in Hawkins Village as a housing authority service coordinator.

Decades ago, the resident council planned parties and cleanup days and brought in programs for the kids, including Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts. Around 2005, though, participation petered out.

Ms. Johnson scheduled an August meeting for residents interested in reviving the council. No one showed.

Azzie Todd’s lingering affection for the complex coexists uneasily with her ambition to leave.

“I walk around this neighborhood. You see kids outside playing. You see people barbecuing,” says Ms. Todd, 49, of Hawkins Village, where she and her husband raised three daughters, now grown, and a son, who is in high school. She gets “a warm feeling, to see the camaraderie of the community. … Usually, I don't see any crime.”

Sometimes, though, you hear it. Her son Jared, 16, says he was playing the video game Fortnite just a week prior, in late November, when he heard a real gunshot. Through his headset, he told his gaming buddies, “‘Another shooting happened.’” In the week that followed, he said, “It was lingering in my head. Did someone get shot? I hope no one got shot.”

“I used to go outside every day,” Jared says.

A few years ago, though, they were transferred from the front of the complex to the back, near the wooded railroad right of way. “Then, like, all the chaos started breaking loose and my friends stopped coming outside,” Jared says.

On July 4, 2016, the Todd family came back to Hawkins Village following a day trip to Presque Isle. “We went in the back door, saw flashing lights and heard people on our porch,” Ms. Todd recounts.

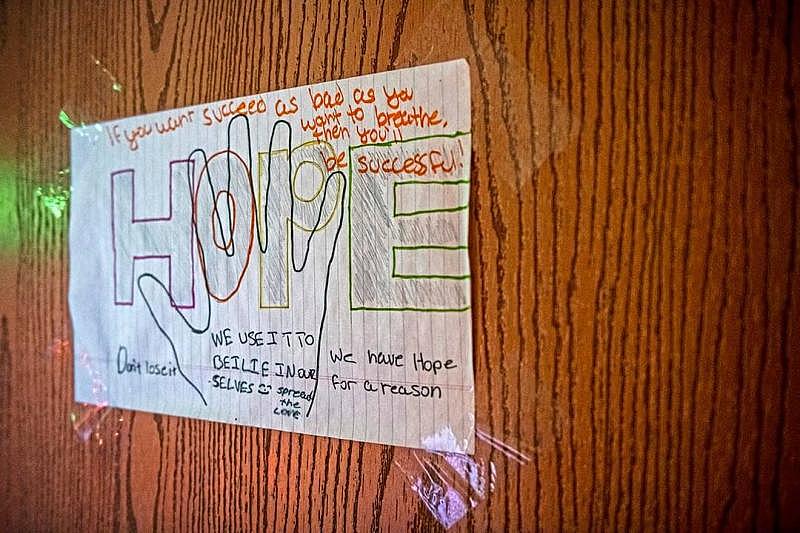

A drawing with the word “Hope” along with inspirational words hangs on the door to Jared Todd's room as he plays the video game “Warframe” at his home in Hawkins Village.

A 14-year-old boy, Kennir Parr, of Swissvale, had been shot in the head just a few yards from their door. He had come there to join aunts, uncles and cousins in setting off fireworks.

In the days that followed, the Todds attended a vigil and balloon launch. “We had a talk with our kids about safety,” Ms. Todd says. “And then life goes on.”

There’s a pile of stuffed animals, deflated footballs and burned-out candles marking the spot where he fell.

On Oct. 17, 2016, Richard McClinton Jr., 26, was shot fatally in Hawkins Village. On Oct. 15, 2017, a 12-year-old boy was injured in a drive-by shooting. And on June 19, Antwon Rose II, of Hawkins Village, was killed by three shots fired by an East Pittsburgh police officer, in an incident that happened two neighborhoods away but spurred protests here.

Ms. Todd describes the effect on Jared: “So it was like a resignation. ‘I’m not going out there any more.’”

He takes the bus to and from Propel Braddock Hills High School, where he is a junior, then comes straight home and plays video games, draws — cartoon characters, hands, flowers, things he sees on YouTube — or writes poems.

“The shootings is kind of how I come up with some of my art,” Jared says. “I wanted to write a poem about the shooting that happened a few days ago.”

“We’ve had an increase in [criminal] activity out there,” says Allegheny County Housing Authority police Chief Michael Vogel. “I attribute it to the age of the young girls moving in there.”

Mothers as young as their late teens can get their own public housing units, he notes. “They’re so vulnerable, and they bring these young guys in, and that’s where the trouble begins.”

A Rankin police Chief Ryan Wooten estimates that 80 percent of the 911 calls in Rankin come from Hawkins Village. “When something critical happens in Hawkins Village, everybody knows about it,” the chief says. “But you know that 'no snitching' thing?” Major crimes, including Kennir’s death, go unsolved.

The housing authority has posted surveillance cameras in Hawkins Village. But most of the trouble happens where the complex meets the tracks.

“Anything can come from the train tracks,” Ms. Todd says. “And people can run to the train tracks, to get away from something they’ve done.”

She works full time handling phones at a community living center and hopes her communications degree from Carlow University, completed in 2013, will help her to move up. She and her husband, who is disabled, assist their three grown daughters, all in college, and try to save enough money to leave Hawkins Village.

After Jared finishes high school, she said, “Who knows? Maybe we move across the country, to Arizona.”

Rankin police officer resigned in August. Then another in September. A third in October.

Chief Ryan Wooten tries not to take it personally. He can pay new members of his part-time, dozen-officer force only $9.75 an hour, and he doesn’t blame them for looking for better-paid, full-time, easier work.

From 2013 through 2017, Rankin reported about the same number of violent crimes as Shaler. Shaler, though, has 13 times Rankin's population and 12 times as much money budgeted for policing.

Last year, Chief Wooten’s departmental budget was $372,162, of which $316,266 covered personnel costs, leaving little for vehicles, gas, supplies, training or anything else. He goes hat-in-hand for equipment, like the computers he just bought with a $3,000 state grant.

That’s how Rankin survives. The roof leaks in the borough building? Apply for a grant. Need a house torn down? Ask the county for money. The basketball court begs for refurbishment? Let local employer Triton Industries pick up the tab. Want to repave a few streets?

Demont Coleman, former mayor of Rankin, left, puts whipped cream on a hot chocolate as Eric Ramsey, center, and Tyshawn Champine, right, both of Rankin, look on during the Rankin Borough Holiday Night, Dec. 12, in the borough building.

“So, no paving this year,” Rankin Borough Council President William “Lucky” Price laments, as he presides over the November meeting of his seven-member body, attended by about a dozen residents. He names a cratered block. “I wanted to get it done this year.”

“The money was approved. The contracts were let out. But Mother Nature didn’t cooperate,” says William Pfoff, council’s vice president. Because of wet and cold weather, the low-bid paving contractor never got around to Rankin.

The borough has a $1.6 million annual budget and has been under state financial oversight for three decades. It shares a public works operation and volunteer fire department with Braddock.

Mr. Price tells his kids and grandkids to stay put. “I didn’t want them to leave, because I always said, we’re going to rebuild this community,” he says. “We’ve got to get a team together, that we can work together to rebuild this community.”

As if Samantha King didn’t have enough reasons to fix her mother’s fire-damaged house on Rankin’s Fifth Avenue, her daughter brought another one home from school.

Ms. King, 44, rents a house on Fourth Avenue, and 16-year-old Shelby got in an argument with a young relative of their landlord. As Ms. King recounts it, the landlord’s relative told Shelby, “‘You irritate me. … I’ll have you evicted.” Shelby’s response? “What? Evict? … We’re moving anyway.”

Would that it were that easy.

The 2016 fire started next door in a rental house. It singed Ms. King’s mother’s house, damaging the roof and one wall. Mom had no homeowners insurance. Years of vacancy took a toll.

Ms. King would like to fast track the remaining painting, flooring, pipe repair and drywalling that would precede a return. “Instead of just paying rent, I could pay taxes and everything, and help out with other stuff, and get things fixed,” she says. “I can’t move fast enough if I don’t have the money to do it.”

Her earnings from an office job with a health system don’t cover much more than the essentials. And in a town with almost no collateral — the King family house is assessed at $11,600 — it’s hard to borrow.

So they rent.

Shelby King-Oliver of Rankin photographed on Fifth Avenue in front of her grandmother's home in Rankin.

“I hate being over here,” Shelby says. “I like the idea of moving in a bigger house and maybe it would take stress away from my mom about bills and it brings back a lot memories,” she texts later.

Would that it could erase a few memories. She knew Vallen Davies-Mack, of neighboring Swissvale, who was 17 when he was shot dead just over a year ago. She was a childhood friend and schoolmate of Kennir Parr, killed in 2016, at age 14.

“I hate it,” she texts, of the violence. “It’s taking my loved ones away and also innocent people.”

Sometimes she’d rather live anywhere else, even just over in Swissvale, where she helps to coach young cheerleaders. Or East Liberty, where she took a multimedia course over the summer. Perhaps Phoenix, where she has family. She jokes that she’d even prefer Uganda.

Would distance ease the feelings of loss?

“No I think I’d always feel the same,” she texts. “Because nothing can replace people.”

When Mr. Weems worked at Target’s corporate headquarters in Minneapolis, he loved the “pedal-to-the-floor” pace. Rankin has a different tempo.

It was July when he and Jaden showed up at the council meeting with barbecue and a proposal to turn Deb’s Place into a kitchen and lease the nearby concession stand as its parking-rich outlet for steaks, ribs, chicken, hoagies and pizza.

Council members sampled the barbecue but made no commitments. In the months that followed, Rankin spent $1,334 adding lights and outlets to the stand.

In November, Mr. Weems stands in the cold and dark Deb’s Place, with, as yet, no contract for the concession stand. “From what I know, they’re working on a lease,” he says. When will it be complete? “Probably when Prohibition comes back.”

Rankin is taking things one deal at a time, Mr. Price says after his council’s December meeting, at which members voted to lease a different lot to another entrepreneur. The concession stand is next in line.

Mr. Weems is getting antsy. After a broken hand cost him a job as a caterer, he found work with a health care system, and Melinda works for a bank. But they have two kids approaching college age, and he knows what it’s like to go to college with a scholarship but not much else. His first bid at higher ed ended after one semester, when his family couldn’t cover expenses. He served three years in the Air Force before returning to school.

Given the restaurant-driven revival in neighboring Braddock and the potential redevelopment of the Carrie Furnace site, he’s ready to place one more bet on “the capital of the world.”

“If the concession stand does nothing, and it’s just flat, then whether it has a good location or not, Rankin is just dead,” he says. “So I sell [the bar], I take my loss on that, and I just walk.”

Mr. Pfoff, the council vice president, hates the fact that he has to cross the river, to The Waterfront, to buy something as simple as a paint brush.

“Prior to the two Palisades being built, you had doctor offices here, you had a hardware store, you had a meat market, Mellon Bank on the corner, and really whether you needed a paint brush or a stapler or a dentist, you didn’t have to leave Rankin,” he says.

Carrie Furnace produced metal from 1907 until 1978 and provided Rankin with jobs, taxes and payments for the water it used. In 1988, U.S. Steel sold the site, along with the rest of the shuttered Homestead Works, to the Park Corp. That Cleveland-based developer transformed the Homestead side into The Waterfront but did virtually nothing on the Rankin side.

In 2005, Park sold the Carrie Furnace to the county for $5.75 million. That made it tax-exempt. So is Hawkins Village. (The housing authority last year made a $2,183 payment in lieu of taxes, based on a HUD formula.) In the county, Rankin trails only Findlay — which hosts the airport — in the percentage of its real estate value that’s untaxable.

For 13 years, the county has been slowly preparing for redevelopment of the Carrie Furnace site, using federal funds to build a $10 million ramp from the Rankin Bridge, paving a road to the old mill, improving the sewers and raising most of the site above the floodplain.

Since the ramp’s completion three years ago, borough officials have been begging the county to market the site.

“I keep telling the county, 'I’m getting older, you going to let me see this? You going to do it during my time here, or what?'” says Mr. Price, 69.

The county put the Carrie Furnace site on the list of places offered to Amazon for a second headquarters. That placed it off limits for other development for most of last year. Finally, on Nov. 14, the day after Amazon chose to build elsewhere, the county invited developers to submit plans for the Carrie Furnace site. The deadline is April 26.

“The Carrie Furnace development, when it’s developed, it’s going to be more or less a wave coming through the community,” predicts Mr. Price. “So we’ve been waiting on that wave, for something to start down there so we can get something going on up here in the community.”

"I just found a name for the store: Dress And Go,” Jaden Weems announces, as he describes his latest entrepreneurial concept, in which customers would go online to design anything from sweatsuits to formal wear, made-to-order.

“Instead of having it made in China and delivering it, it'll be made in that store,” he says. “As soon as you order it, we'll be like, ‘OK, we'll have it prompt in like three or four hours.’”

Mr. Weems loves his son’s ambition and his daughter’s drive to study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Sometimes, though, he worries that his kids, both of whom take advanced courses at Woodland Hills, occupy an uneasy bridge between two worlds. “We've got Forest Hills on one end and Rankin on the other end. And we're in the middle. And you can’t really be both. But I want them to be both.”

He can feel the tension between Rankin’s inertia and his efforts to improve his family’s situation. Push too hard? “You become the smart-ass. You become the know-it-all.” That can blow back on the kids.

So as he mulls expanding the family home, putting in a dormer and a deck, a new kitchen and a larger bathroom, he has to think about how that will be viewed. “That's something that doesn't really happen around here, so you've got to be careful,” he says. A big, visible home improvement can cause “issues [for the kids] at school. ‘Oh, ya’all think ya’all got money.’”

He looks out his front window, to the empty lots across the street that wait for the wave to come up from the furnace site below. That urge to invest in “the best city” surfaces again.

“We could buy that space and build there,” he muses. “But do we want to spend the rest of our lives in Rankin? I don’t know.”

[This story was originally published by Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.]