Repairing broken bonds: How families rebuild ties after migration

Melissa Noel reported this story with the support of the International Center For Journalists ‘Bringing Home The World International Reporting Fellowship,’ The Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Jamaica's 'barrel children' often come up empty with a parent abroad

Claudette Higgins with her youngest son in Westmoreland, Jamaica. Courtesy Claudette Higgins

NEW YORK — After years of working as a street vendor in Jamaica, her native home, Claudette Higgins, 59, immigrated to the island of Antigua in 1994 for consistent and higher-paying work in the hotel industry to support her family.

At the time, her oldest child, Dwight, was 11 and her youngest, Roxanne, was barely a toddler. She had to leave them in the care of relatives in Jamaica. “I didn’t have the means to bring them," she said. "It was really hard."

Higgins regularly sent cash via money transfer services such as Western Union and Money Gram. When possible, she would send barrels full of clothing, food and other necessities to her children. Their relationship still suffered, she said with sadness in her voice.

“They knew me as their mother, but we didn’t have a mother-to-child relationship," she said. "They knew that their mother was in Antigua and that whoever was taking care of them was not their mother.”

After living and working in Antigua for 14 years, Higgins migrated once again to support her family, this time to the United States. She settled in the Bronx in 2008.

Now that her children are adults, their relationship has improved. They’ve shared painful memories of physical and verbal abuse suffered during her absence and how being apart for more than two decades has forever affected their lives.

“You know when you are not physically there and the child is not able to speak with you, the parent, one-on-one, it’s not the same because sometimes things happen that you’re not even aware of,” Higgins said with a heavy sigh, her voice cracking. "It made me very sad and angry."

Claudette Higgins is one of an estimated 244 million migrants around the world. While some have been forced from their homes because of political turmoil or persecution, others, like her, leave voluntarily seeking economic opportunities to improve the quality of life for themselves and their children.

The emotional and psychological trauma of separation

Experts say separation issues experienced by child and parent don’t just resolve themselves over time. Reuniting after years apart without addressing feelings of detachment or resentment won’t improve a strained relationship.

“The longer apart these children are from their parents, the more trauma sets in,” said Andrea Crichlow, a Brooklyn-based social worker from Barbados. For the past 17 years, she has counseled families facing adjustment issues after reunification.

“This is a total culture shock," she said. "There’s snow. There’s a new accent they are dealing with, and new schools. They’re the outsiders, so the culture shock in many cases is a lot to handle, and sometimes the parents don’t understand that they needed to prepare a child and be prepared for the reintegration of the child back into their household or have a plan for the initial integration.”

Monique Campbell was 15 when she emigrated from St. Andrew, Jamaica, to join her mother in Brooklyn. They had never lived under the same roof and she was not prepared for the transition.

Campbell, now 27 and working in marketing, said she was excited at first, but found the experience both awkward and difficult. With nervous laughter she recounted trying to fit into her mother’s new life.

“She had remarried, she had [another] child, so I didn't know what it would have been like to come into a situation where it was her and her family, opposed to her being on her own," Campbell said. "I was learning how to exist with this woman who was sort of a stranger."

Campbell lamented that the experience has affected other relationships. She struggles to open up to people and show emotion or vulnerability. After almost 12 years, she said she is still unsure about how to approach a conversation with her mother about the effects of their separation.

“I get why she had to do it. Because of her I'm sitting right here, because of her I went to college," she said. "But I think that oftentimes we need to really take a step back and think about the impact,” she said.

Monique Campbell at her kindergarten graduation in Jamaica. She made the short film Missing Melodie about migrating to the U.S. and the difficulty in her family reunion not being what she expected. Courtesy Monique Campbell

Communication, Crichlow said, is one aspect of the parent-child relationship that often needs the most nurturing, both during a separation and after a reunion.

A lack of communication was the biggest issue Errol Wray Jr. says he faced after reuniting with his father in 2012; he was 16 and had been raised by his mother in Jamaica, so didn't really know his father growing up.

“It was rough because I didn’t know what he wanted and he would expect me to know certain things but I just did not know,” Wray said. “In my head I’m thinking, ‘I don’t read minds, I would like you to say it.'"

"Then I come here and I’m like, I just want my dad to talk to me," he said.

Wray, now 22, was just a few days old when his father, a plumber and a mason, migrated to the United States in 1995. His father would send him money and barrels full of goods home to Jamaica.

Errol Wray Sr. 48, acknowledges that his absence in the early years of his first-born’s life had a major impact on their relationship. Though they spoke on the phone once a week and saw each other once a year, Wray Sr. said that he missed out on the everyday conversations that only a father and son can have. “I missed many of those, so those were some of the hardest things for me," he said. "It hurt me."

The legal process to reunite

What made it even harder for Wray Sr. was how long the immigration process for his son was. “The process can destroy families," he said. "It frustrates you as a parent. It’s a lot of frustration, and every day it feels like the fees are going up and the time you’re away from your child gets longer."

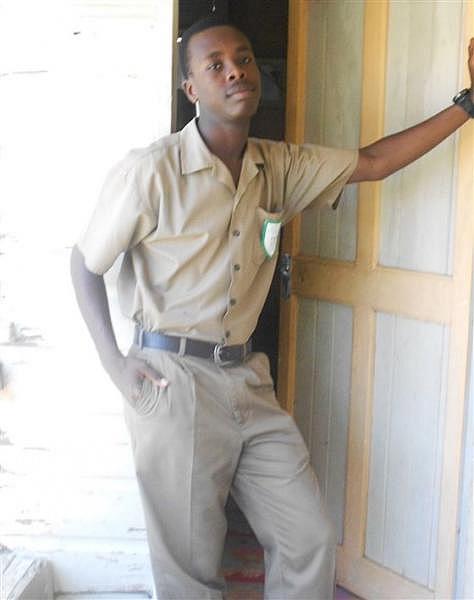

Errol Wray Jr. in school as a child in Jamaica. Courtesy Errol Wray Jr.

In 1998 Wray Sr. applied for a visa for his then 3-year-old son. It was deemed incomplete because of what he said was misinformation given by a lawyer. When that application was denied, Wray Sr. decided to wait until his son was older before he reapplied in 2005. It took another six years before the process was complete and his son was granted a visa to enter the United States and join him in the Bronx.

President Donald Trump’s new immigration proposal includes calls for a massive decrease to legal immigration by limiting family reunification, also called chain migration, to spouses and minor children only.

This would put more pressure on a system that is "already riddled with sometimes 12-year wait periods or longer," said Diron Rutty, a family and immigration lawyer based in the Bronx.

It could also "further delay the time it takes for families to reunite after they apply for a green card,” Rutty said.

She encourages immigrant parents to continue to apply for their children under the current system, but underscores the need for them to factor in the time it will take, the visa quotas that exist and the toll it can take on their family.

A new life moving forward

Although there are resources available for immigrant families across the U.S., there is no single comprehensive federal program that addresses all of the issues they may face during years of separation.

“We have identified that there is not a solid platform, but there are pieces that exist like the lawyer, the pastor, the church,” said Navlett Coleman, pastor of Lighthouse Ministries International in the Bronx.

“If we can come together and form that coalition, or that platform, where people know that, ‘Hey, I’m coming to the country’ or ‘I’m a child that’s been separated or a parent that has been separated from when my child was 3 years old and this is a place I can go for counseling,’ that would have impact,” she said.

As a part of her ministry, Coleman connects her church community to legal, medical and educational services as well providing counseling services to help mend family relationships. It has helped the Wrays, father and son, make it through a rough adjustment period.

Errol Wray Jr. (left) with his two younger sisters and his dad Errol Wray Sr. during a family night out in New York City. Courtesy Errol Wray Jr.

“It was a total different thing, so for him to transform from what he was accustomed to something different was a real challenge for him, and likewise for me," Errol Wray Sr. said. "We tried to work it out to the best way we know how to do it, and wead some support."

Five years after reuniting, father and son see their relationship in slightly different ways.

“I feel like we’re getting there," said Wray Jr., now a psychology major at the Borough of Manhattan Community College. "We have some way to go, and it’s work in progress.”

His father was more confident.

“I think our relationship is good now," Wray Sr. said. "He didn’t get me then. He may still not get me now, but eventually he’ll get me.”

[This story was originally published by NBC News.]