Report offers plan to cut child poverty in U.S. in half in 10 years

Michael M. Santiago/Post-Gazette

By Kate Giammarise

Child poverty harms kids, and costs the U.S. between $800 billion and $1.1 trillion annually in myriad ways such as health care costs, crime, and reduced productivity, according to a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released Thursday.

The effect of poverty on kids is about more than dollars, said Dr. Benard Dreyer, a member of the committee that wrote the report and professor of pediatrics at NYU School of Medicine. He noted that “being poor is extremely stressful for parents. When you can't get food on the table, it's harder to say, 'I need to read “Goodnight Moon” to my little child.'”

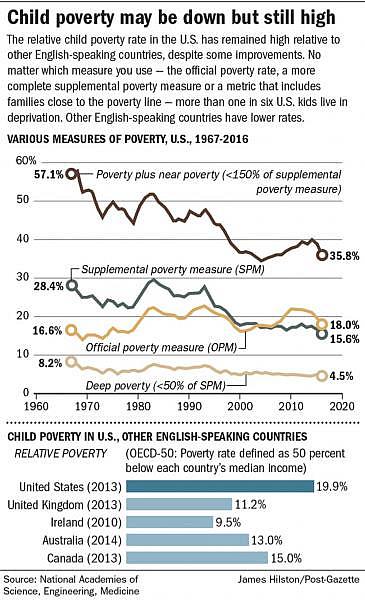

Nationwide, more than 9.6 million kids lived in poor families in 2015, with about 2.1 million of those children in “deep poverty,” meaning their families had resources below half of the poverty line. The report used what is known as the Supplemental Poverty Measure because researchers said it is a more comprehensive measure of poverty, and it includes public benefits such as food stamps and tax credits.

“A wealth of evidence suggests that a lack of adequate family economic resources compromises children’s ability to grow and achieve success in adulthood, hurting them and the broader society as well,” the report notes.

Cutting the child poverty rate in half would cost between $91 billion and $109 billion, the researchers estimated.

“Outlays for new programs that would reduce child poverty by 50 percent would cost the United States much less than these estimated costs of child poverty."

The ongoing Pittsburgh Post-Gazette series Growing Up Through the Cracks, is focused on the harmful impacts of concentrated child poverty on kids, families and communities locally.

In seven Allegheny County communities, half or more kids live in poverty: North Braddock, Mount Oliver, Rankin, Duquesne, McKeesport, Clairton and Wilmerding.

While the report paints a bleak picture of how poverty can hurt kids, it emphasizes the problem is solvable, or at least, somewhat solvable.

“Both the U.S. historical record and the experience of peer countries show that reducing child poverty in the United States is an achievable policy goal,” the study notes.

Poverty-fighting programs “have been shown to improve child well-being,” the report notes, citing increases in the generosity of the Earned Income Tax Credit that have “improved child educational and health outcomes,” improved health for kids and adults from the food stamp program and “substantial improvements in child and adult health, educational attainment, employment, and earnings” from expanded health insurance programs for pregnant women, infants, and children.

“Actually, we can do this, if we want to,” Dr. Dreyer said, of the goal of reducing child poverty.

Source: National Academies of Science, Engineering, Medicine; James Hilston/Post-Gazette

Two packages of a combination of programs could meet the goal of a 50 percent child poverty reduction, the report notes:

• One package would combine bolstering work-related programs such as an expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit and the child dependent care tax credit, along with expanding “means tested” programs for families below a certain income level such as food stamps and housing vouchers. The committee estimated these programs would cost $90.7 billion per year.

• Another package would combine programs for low-income workers such as an expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit and the child dependent care tax credit, increasing the minimum wage, and universal programs like a child allowance. It would also end restrictions on immigrants receiving certain public benefits that were part of the 1996 welfare reform law. This package is estimated to cost $108.8 billion per year.

• A third potential package would expand the earned income and child dependent care tax credits and offer a child allowance. At a cost of $44 billion annually, it would reduce child poverty by a third.

A child allowance would be paid monthly, not yearly, said Timothy Smeeding, one of the report's authors and a professor of public affairs and economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “Poor people live month to month, not year to year,” he said.

“We really tried to cast a broad net and come up with an assortment of ideas,” said Greg Duncan, a professor at the University of California, Irvine and chair of the committee the authored the report. No single program or policy option alone met the goal of a 50 percent child poverty reduction, he said, speaking Thursday at a Washington, D.C. press conference.

The study, which represents nearly two years of work, was sponsored by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Foundation for Child Development, Joyce Foundation, Russell Sage Foundation, W.K. Kellogg Foundation, William T. Grant Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Additionally, on Thursday, a partnership of more than 20 anti-poverty groups, The U.S. Child Poverty Action Group, announced they would launch End Child Poverty U.S., a campaign to cut child poverty in half in 10 years and end it in 20 years.

Kate Giammarise: kgiammarise@post-gazette.com or 412-263-3909. This story was produced with assistance from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism‘s Data Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by the Post-Gazette.]