A Rise In Suicides In LA Jails Underscores A Troubling Lack Of Mental Health Care

The story was originally published in LAist with the support from USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's Data Fellowship.

Conditions inside L.A. County jails have long been a problem — particularly when it comes to the care of incarcerated people with mental illness who make up a substantial percentage of the more than 14,000 people behind held on any given day.

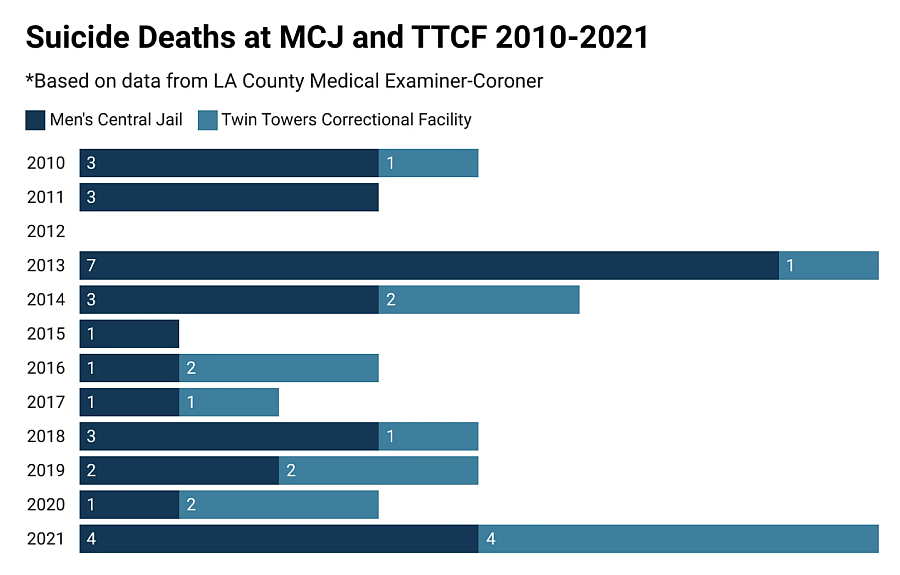

Jail officials and county-appointed monitors alike say current care in the jails is severely deficient. Now an LAist review of coroners' records finds 2021 marked the highest number of deaths by suicide inside the downtown jail complex in eight years.

The rise in suicide deaths comes at a time when the L.A. County Jail system is plagued by a number of issues: Facilities are overcrowded, jail officials are struggling to maintain a mental health workforce, and the jails are out of compliance with requirements mandated by federal court.

“Jail is not the answer,” said Marlene Carrillo, a widow and mother of five whose husband died by suicide at Men's Central Jail in 2021. “It doesn’t help them ... just throwing them in jail and ignoring the fact that they’re struggling within their own mind.”

The suicide of Mark Carrillo and seven others that same year at Men’s Central Jail (MCJ) and Twin Towers Correctional Facility (TTCF) marked a sharp uptick — the previous decade those facilities averaged three suicide deaths a year, according to LAist's analysis.

The 2021 cases — the most recent year with complete data — reveal serious concerns about the ability of the overcrowded jail system to care for people who are in severe distress and at high risk for suicide.

Why some call it a ‘human rights crisis’

Mark-Anthony Clayton-Johnson regularly sees conditions inside L.A.’s jails as chair of the Sybil Brand Commission, an up to 10-member body appointed by the L.A. County Board of Supervisors tasked with performing jail inspections. He said jail conditions downtown make for a “human rights crisis” that can only get worse.

“It is a recipe for hopelessness,” said Clayton-Johnson.

Eric Miller, a Loyola Law School professor and Sybil Brand commissioner, described some of the conditions he observed last summer as “something out of Charles Dickens,” with several men naked in “filthy” cells.

It’s truly disgusting the sorts of conditions that we subject people with serious mental illness.

Eric Miller, a Loyola Law School professor and Sybil Brand commissioner

“It’s truly disgusting the sorts of conditions that we subject people with serious mental illness,” Miller told LAist. “It’s clear that people are just getting worse when they're held under those circumstances.”

In an emailed statement, the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department said it is working with several stakeholders to address complex challenges “we all collectively face in our jails.”

The statement goes on to say:

“Our jails and our population have seen changes over the last few years requiring an even greater focus on our increasing mentally ill population. We remain committed to best practices related to the safety and security of those in our custody while also providing a constitutional level of care.”

Why some say it is ‘impossible to provide adequate treatment’

L.A. County’s Correctional Health Services (CHS), which is responsible for managing medical care for people incarcerated in county jails, continues to struggle to maintain its mental health care workforce.

Joan Hubbel, a mental health program manager for CHS, said at a February meeting of the Brand Commission that there was a roughly 44% vacancy rate for jail mental health staff. Hubbel said there are 376 budgeted mental health positions and at that time 163 were unfilled. Hubbel added that 60 people were in the process of onboarding to fill some of those empty positions, so the vacancy rate could soon drop to 27%.

The mental health staffing shortage comes at a time when the jails’ mental health population is continuing to increase. Advocates point to a lack of mental health treatment beds in the community and slow movement on the county’s “Care First, Jails Last” approach, which prioritizes jail diversion programs over incarceration, as part of the problem.

The acuity and the sheer number [of people with a mental illness] have made it such that it’s impossible to provide adequate treatment in this facility or in the jail system.

Dr. Timothy Belavich, director, Correctional Health Services

A report late last year from the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department noted that people with mental health needs then stood at about 40% of the overall jail population. During the fourth quarter of 2021, the mental health population stood at 5,715 and comprised 43% of the total average inmate population of 13,319.

At a Brand Commission meeting in Sept. 2022, Dr. Timothy Belavich, the Correctional Health Services told commissioners: “The acuity and the sheer number [of people with a mental illness] have made it such that it’s impossible to provide adequate treatment in this facility or in the jail system.”

Later that year, Belavic told commissioners: “Not everyone wants to come work in the jail, and not everyone is ready for that type of work.” He noted that the L.A. County Department of Mental Health is also struggling to fill open positions.

Shortages of clinicians make the intractable task of caring for people with serious untreated mental health conditions all the more difficult, said Dan Mistak, director of health care initiatives for justice-involved populations at Oakland-based Community Oriented Correctional Health Services.

The Los Angeles County Twin Towers Correctional facility in downtown Los Angeles.

(Andrew Cullen for LAist)

“I often call the jail the emergency department of the criminal justice system,” said Mistak, whose group monitors incarcerated people's health care. “Because you get people coming in at all hours of the night [and] you don’t really have a long history of understanding what’s going on with them.”

At the jail complex in downtown L.A., all incarcerated people undergo an initial screening with a nurse. In his report from last fall, Nicholas E. Mitchell, an independent monitor appoint by the Department of Justice to oversee jail conditions, expressed “concern” that his team “has continued to find patients with urgent or emergent conditions that were likely present at the time of the intake screening that should have been detected during a standard intake process but were not detected.”

Mistak said things like depression and suicidal ideation get missed by intake screenings.

“And then on top of that you’re placing them in what is far, far, far away from being a therapeutic environment,” he said.

According to the Sheriff’s Department, the Inmate Reception Center processes some 120,000 people a year.

The Sheriff’s Department maintains two Jail Mental Evaluation Teams (JMET) made up of a deputy and mental health clinician that are tasked with assessing people locked up at the downtown complex to see if they need further mental health assessment or transfer to more appropriate housing.

What happened in the case of one suicide

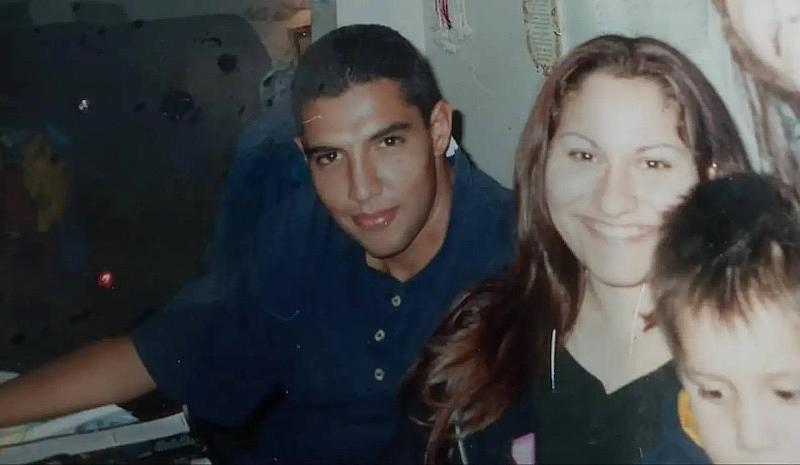

Mark and Marlene Carrillo

(Courtesy of the Carrillo family)

In Jan. 2021, Mark Carrillo died by suicide inside a cell at Men’s Central Jail (MCJ).

According to coroner records obtained by LAist, Carrillo was the second of four people to die by suicide at MCJ in 2021. His final incarceration in the L.A. County Jail system was due to a probation violation stemming from a 2015 conviction of methamphetamine possession with the intent to sell.

Carrillo’s wife, Marlene Carrillo, remembers the 38-year-old father of five as a loving and caring person. “His family was his everything, his world,” she said.

A wrongful death lawsuit filed in July 2021 by attorneys on behalf of Marlene Carrillo and her children against L.A. County and then-Sheriff Alex Villanueva states that Mark Carrillo was diagnosed with schizophrenia around 2018. That was some two years before his last incarceration.

Marlene Carrillo said it became extremely stressful and overwhelming for her to try to help her husband with his mental illness while also taking care of their children.

“He also apologized for putting more on me by him having mental [illness]. Now, after the fact ... memories is all I have,” she said. “He tried to control it, but it’s uncontrollable.”

Marlene Carrillo said they were unhoused at some point, and her husband was struggling to keep checking in with his probation officer.

According to the complaint, Mark Carrillo was incarcerated some seven times between 2019 and 2020 and had attempted suicide on “multiple occasions” while he was locked up previously.

Carrillo, the complaint alleges, “had a known mental health illness and known suicidal ideations, he was not given medication, nor was treated properly by a psychiatrist. He was simply left to languish.”

Due to his diagnosed serious mental illness, prior suicide attempts and other factors, the lawsuit posits that Carrillo should have been placed in High Observation Housing (HOH) at Twin Towers during his final incarceration, but was not.

Activists calling for the closure of Men's Central Jail rallied in downtown L.A. in March, 2021.

(Robert Garrova/LAist)

In 2021, the year Carrillo died, there was on average about 1,000 people in HOH at Twin Towers. A Jail Mental Evaluation Team can refer someone for placement in HOH, which is supposed to include more frequent safety checks.

Jail is not the answer. It doesn’t help them ... just throwing them in jail and ignoring the fact that they’re struggling within their own mind.

Marlene Carillo, whose husband, Mark, died by suicide in the Men's Central Jail

The complaint says Carrillo was placed in a single-man cell at MCJ “just prior to his death.” The coroner’s spreadsheet marked the cause of death as “hanging.”

Mark and Marlene Carrillo

(Courtesy of the Carrillo family)

"This man was sending out warning signals, bright red lights: 'I need help, give me help.' But nobody took it upon themselves to take that next step to do something about it and say, 'Hey, let’s transfer you, let’s make sure you’re getting the care you need,'" said the family’s attorney, Michael Carrillo (no relation).

Marlene Carrillo and her children settled their wrongful death lawsuit for $2.5 million, contingent upon the approval of the L.A. County Board of Supervisors.

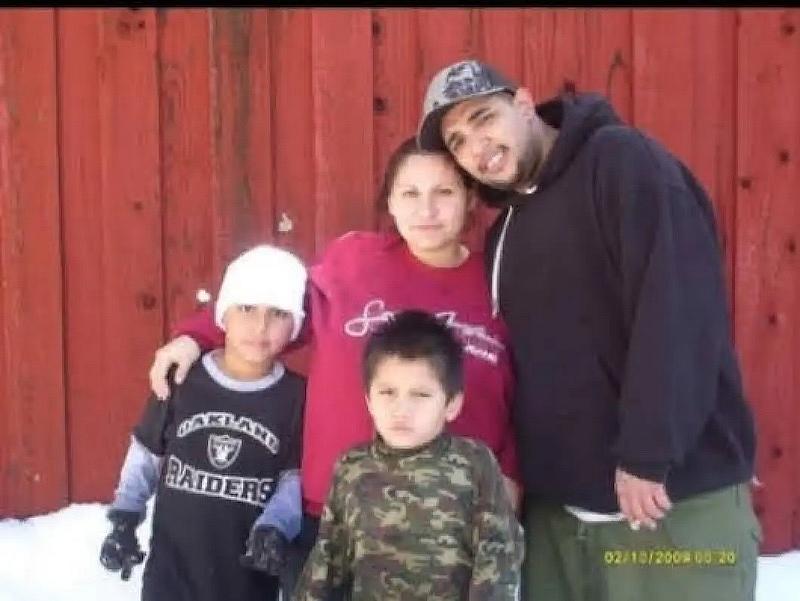

The Carrillo family

(Courtesy of the Carrillo family)

Marlene Carrillo said her husband's death hasn’t really sunk in for her five children yet, who used to enjoy playing baseball and going to the park with their dad. The youngest was 2 years old when Mark Carrillo died.

Carrillo said she thinks more attention needs to be paid to people who go to jail with mental health concerns.

“Jail is not the answer,” she said. “It doesn’t help them ... just throwing them in jail and ignoring the fact that they’re struggling within their own mind.”

L.A. County declined to comment on the Carrillo case, according to an email from a spokesperson for the county's Chief Executive Office. A spokesperson for the Sheriff's Department said in an email that “our heart go out to the families of Mr. Mark Carrillo ... Unfortunately, we are unable to comment on pending litigation and on circumstances related to an inmate’s death."

A ballooning mental health population

In 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice entered into a settlement agreement with the county after a DOJ investigation into mental health care at county jails “found a pattern of constitutionally deficient mental health care for prisoners, including inadequate suicide prevention practices.”

In 2021, the suicide rate at the jail complex downtown (TTCF and MCJ) was about one per every 1,000 people. That’s more than 10 times the suicide rate for L.A. County in 2020.

Mark-Anthony Clayton-Johnson is the Sybil Brand Commission chair and executive director of the advocacy group Dignity and Power Now.

(Courtesy L.A. County)

Clayton-Johnson, the Sybil Brand Commission chair, said he talked with an incarcerated person on a recent jail inspection who said he didn’t see a clinician for more than a month after being taken off suicide watch, when safety checks are required every 15 minutes.

Last year, people who work at and are familiar with conditions inside the jails system told LAist that people are not receiving care in a timely manner and staffing shortages are part of the problem.

“For people who are self-harming, the follow-up and the plan-making and all that, there’s deficiencies in the ability of the jail system to meet the criteria and meet the actual settlement agreement,” said Clayton-Johnson, who also serves as executive director of the advocacy group Dignity and Power Now.

Mistak of Community Oriented Correctional Health Services (COCHS) said that, ideally, if somebody is in jail and in the midst of a mental health crisis, they should be diverted to a more appropriate setting.

“If somebody is at risk of suicide, they’re not going to become less at risk over time after being incarcerated, particularly if they’re going to be put in a cell just by themselves,” he said.

While the county has invested millions of dollars into the Office of Diversion and Reentry, which has the goal of diverting people living with mental illness from jails into community-based care, the program has struggled to meet demand partly because of a lack of funding. And the jails’ mental health population has continued to balloon.

“Our jails and jail population have seen changes over the last few years requiring an even greater focus on our increasing mentally ill population,” the county CEO spokesperson said in their emailed statement. “We remain committed to best practices related to the safety and security of those in our custody while also providing a constitutional level of care,” the county said.

A mother says son's death ‘could have been prevented’

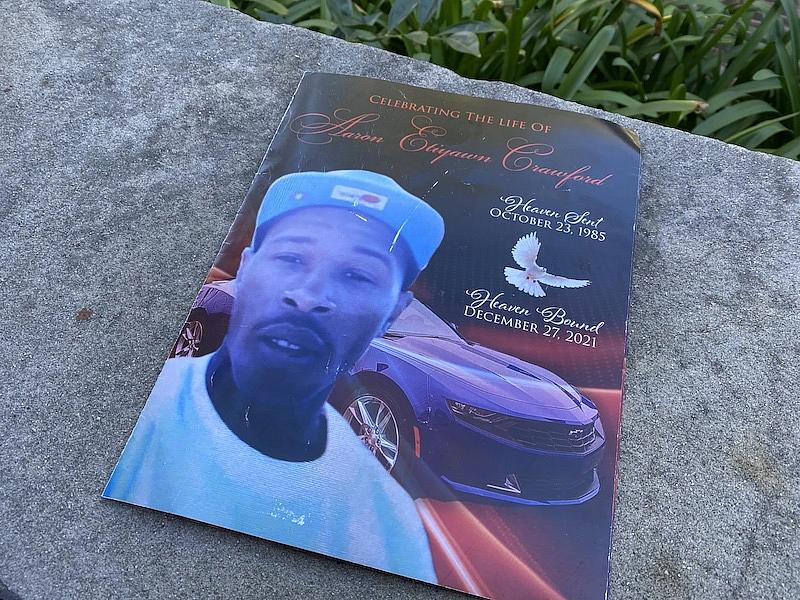

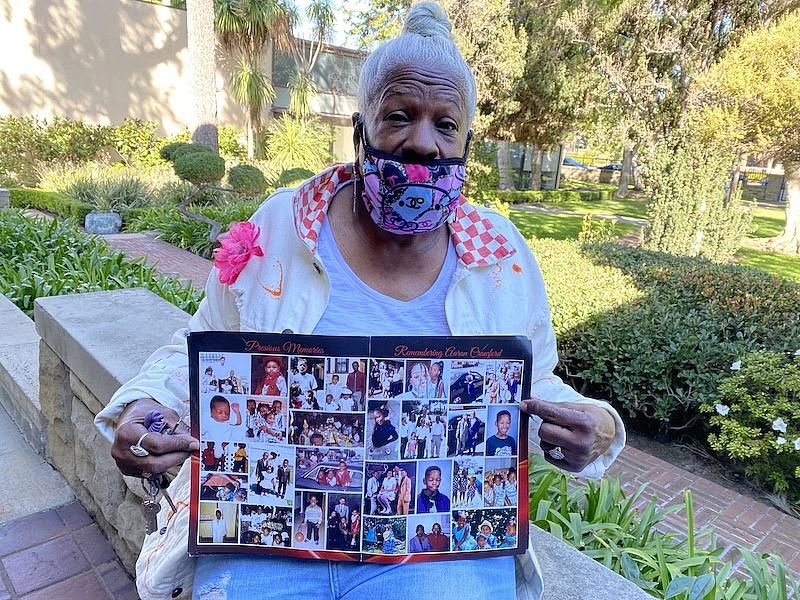

A memorial program for Aaron Crawford

(Robert Garrova LAist)

Aaron Crawford was the last person in 2021 to die in-custody at the downtown jail complex, according to coroner data and family accounts. His mother, Debra Johnson, said she keeps her son’s ashes in a necklace. She remembers Crawford as someone who could enter a room and make everybody laugh, as an excellent dancer and as someone who loved Chevrolets and family.

“He would do anything for his family,” Johnson recalled.

Crawford was convicted of murder in 2021. He died by suicide at Twin Towers on Dec. 27, 2021, before he was sentenced. He was 36.

Crawford had a difficult upbringing, Johnson said. As a child, the Department of Children and Family Services removed Crawford and his sister from their home, claiming Johnson wasn’t providing adequate supervision, Johnson said.

Debra Johnson holds a poster of family photos that include her son, Aaron Crawford.

(Robert Garrova / LAist)

She said Crawford bounced around between placements as a child and for a time lived at MacLaren Hall, a facility infamous for abuse allegations. Johnson said she believes Crawford suffered abuse as a child.

Although the exact timeline is unclear, Johnson said Crawford was diagnosed with schizophrenia at a young age.

“I’ve been yelling since the first time he was arrested — [at] probably 18 — 'he has a mental problem,'" said Crawford’s sister Mikiya Davis.

Davis said Crawford had attempted suicide on more than one occasion while incarcerated and she questions to this day how her brother was able to take his own life behind bars.

The jails continue to be out of compliance with the 2015 federal settlement agreement that required the county to rectify several serious concerns about patient care, according to a Sept. 2022 report from a court-appointed monitor who observes conditions in the jails. The U.S. Justice Department recently drew harsh criticism from four U.S. Senators for failing to take more action to fix the problems.

Monitor Nicholas Mitchell wrote in his latest report that the county “continues to struggle to appropriately intervene when inmates with mental illness engage in self-injurious behavior in jail.”

Mitchell wrote that reviews from a team of mental health experts “reflect that the County remains seriously — possibly dangerously — unable to provide appropriate, tailored interventions when inmates with mental illness decompensate and engage in acts of self-harm.”

For her part, Johnson said she’d like the Sheriff’s Department to be held accountable for her son’s death.

“It could have been prevented,” Johnson said, adding that she’s currently trying to find an attorney interested in filing a wrongful death lawsuit on her behalf.

Davis said she knows her brother deserved to be in jail for taking another life. But she sees Crawford’s story as the tragic outcome of child protective services, the criminal justice system and the mental health care system all failing her brother.

“He was being locked up at an early age for things that should not have been ... jail ... These boys are being locked up for things that are not criminal, it’s mental,” Davis said.

L.A. County declined to comment on Crawford’s death or the circumstances that led up to it, according to the CEO spokesperson's statement.

Death records under the microscope

According to coroner data, 2021 saw an increase in in-custody suicides overall. In 2021, there were 12 in-custody suicides. Besides the eight at the downtown L.A. jail complex, people also died by suicide at the Century Regional Detention Facility in Lynwood, the Palmdale Sheriff’s station and a police station in Torrance.

Helen Jones of Dignity and Power Now spoke at a June 2022 rally at the Hall of Justice. Her son, John Horton, died inside Men’s Central Jail in 2009.

(Emily Elena Dugdale / LAist)

Meanwhile, activists and researchers have questioned the accuracy of coroner records from previous years.

Researchers at UCLA’s Carceral Ecologies Lab and the BioCritical Studies Lab looked at 59 autopsies between 2009 and 2019. While the autopsy reports claim that roughly half of those individuals, or 26 people, died of natural causes, “85% of these ‘natural’ cases involved alleged mental illness and 54% included evidence of physical violence on the body,” the UCLA study says. The study, by UCLA’s Terence Keel and Nicholas Shapiro, suggests that some incarcerated people are not dying from reported natural causes, but “from the actions of jail deputies and carceral staff.”

Helen Jones’ son John Horton died in solitary confinement at Men’s Central Jail in 2009. Jones believes her son, 22, was beaten to death by deputies involved with the 3000 Boys, a deputy gang operating in the jail. The county has labeled the cause of Horton’s death as “undetermined,” but initially ruled that he had died by suicide.

“I knew it wasn’t a suicide from day one. I know John,” Jones told LAist.

In March, Jones joined other activists with JusticeLA for a rally outside the coroner’s office to draw attention to what she and others believe is a misrepresentation of deaths in L.A. County jails.

“They don’t want to say this is a murder, so they just leave it ‘undetermined’ to where [they’re saying] ‘y’all prove it now what it is,’” Jones said.

Earlier this month, the coroner's office released a statement in response to the BioCritical Lab’s study.

“It has been suggested that classifying the cause of death as ‘undetermined’ is improper or irregular, and that this manner of death negatively impacts a criminal trial. However, classifying the cause of death as ‘undetermined’ is a well-accepted practice among medical examiners nationwide, and the classification does not prevent any criminal proceedings or investigations from occurring,” the statement said.

It added that the coroner's office “will continue to offer unbiased and independent determinations in all of our cases.”

What's next: new programs and a push to close Men's Central Jail

Protesters rallied on March 30, 2023 to call on L.A. County to close Men's Central Jail by March 2025.

(Robert Garrova / LAist)

Dan Mistak of COHS said that for him, the interaction of mental health and the justice system “is a picture of some of our most intractable problems.”

But he's hopeful about a new program that’s slated to allow incarcerated individuals to take advantage of some Medi-Cal benefits 90 days before their release. Mistak said services could include case management, consultation with outside providers and medication-assisted therapy.

“It’s a completely different world," he said. "It will allow for the community mental health system to actually be able to reach inside the jail and be paid for those services for the first time literally ever.”

Still, the increase in suicides at the downtown jail complex comes at a time when L.A. County continues to move slowly on its promise to significantly change the jail system.

In 2021, a report by the county’s Department of Diversion and Reentry and the Sheriff’s Department estimated it would take up to two years to close Men’s Central Jail. The report described the nearly 60-year-old facility as "unsafe, crowded and crumbling."

The proposal cites a 2020 RAND study, which found that “an estimated 61% of the jail mental health population were likely appropriate candidates for diversion.”

One year after the Board of Supervisors received the report on closing Men’s Central, it said in a statement that while it’s committed to closing the jail “as swiftly as possible … it is difficult to project an exact timeline.”

In the statement from the CEO spokesperson, the county said it:

“[c]annot safely depopulate and then close Men’s Central Jail without first ensuring that a dynamic network of community-based care is in place and securing the full cooperation of the courts, prosecutors, and other law enforcement agencies in diverting or releasing individuals from jail.”

The county said the MCJ population must be cut in half before it can begin shutting down the facility. According to the county, several agencies, including the Department of Mental Health and the Office of Diversion and Reentry, “are in the process of building out a robust network of community care that would provide alternatives to custody that could be utilized by those with the authority to release individuals from custody.”

Last year, the ACLU urged a federal court to order immediate improvements to conditions at Los Angeles’ Inmate Reception Center (IRC), which is at the Twin Towers Correctional Facility. The ACLU described the conditions at the IRC as “abysmal,” and alleged its attorneys who recently visited the facility saw “[p]eople with serious mental illness chained to chairs for days at a time, where they sleep sitting up ... People defecating in trash cans and urinating on the floor or in empty food containers in shared spaces,” and several other disturbing observations.

“L.A. County agrees that the conditions in the Inmate Reception Center have not been acceptable in the past,” the CEO spokesperson's statement said. County officials said they're doing everything in their power to comply with the court orders, including:

- "assigning additional mental health staff to the IRC Clinic"

- "converting general population beds into mental health beds"

- "designating a supervisor on each shift to ensure compliance"

- "taking additional steps to ensure that individuals awaiting mental health assessment are provided with access to beds, blankets, restrooms, showers, telephones, and medical care"

Clayton-Johnson of Dignity and Power Now and the Sybil Brand Commission said that during a recent jail inspection of TTCF he observed a person who had smeared feces on the walls of a cell. He said poor hygiene conditions coupled with delays in receiving care make for a dire situation.

“It is a recipe for something bad to happen ... it is a recipe for hopelessness,” Clayton-Johnson said.

He believes adequate mental health staffing within the jail system is not a panacea. Clayton-Johnson would like to see the county set up more mental health treatment beds in the community “to stop people from ending up in [jail] in the first place.”

He called this a “critical moment around whether the county will be steadfast in its trajectory” to close Men’s Central Jail.

“Without a concrete timeline to close Men’s Central Jail, this regressive reality that we’re in — which is really a human rights crisis — is just going to get worse,” Clayton-Johnson said.