The role of culture and language in tackling loneliness

This story was originally published in KALW with support from the 2022 California Impact Fund.

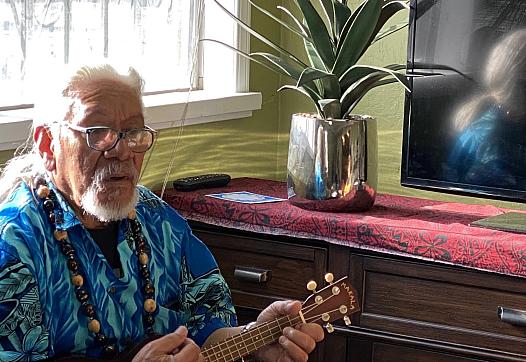

Sharing traditional songs and music are part of Papa Senita's approach to supporting mental wellness in his community

Liza Ramrayka/KALW

In part one of a series on mental health in AAPI communities, we look at community-grown solutions helping seniors in San Mateo county address loneliness and depression.

We try to de-stigmatize mental illness, because we’re culturally one of the groups of people that stigmatize mental health.

Leafa Taumoepeau, executive director of Taulama for Tongans

The San Francisco Bay Area is home to the largest Tongan population in the state, and toone in five of California’s Pacific Islanders.

The majority of East Palo Alto’s Pacific Islander community come from Fiji, Samoa or Tonga – actually more than 20 communities. Each of these island nations has its own language, its own unique racial and religious mix, its own distinct characteristics.

Language barriers, lack of culturally sensitive services and mistrust of government institutions are some of the things that prevent people from different Pacific Islander communities from getting the support they need. But grassroots groups are finding solutions to the isolation and depression they see impacting PI seniors.

Senita ‘Uhilamoelangi – known locally as Papa Senita in his community of Tongan and Pacific Islanders – has lived in East Palo Alto for over 50 years. He came to the U.S. after performing in bands all around the Pacific Islands with his ukelele and his guitar.

In 2003, Papa Senita was at his local church, rehearsing Christmas songs, when he got caught in gang crossfire and was shot in the leg.

“We were getting ready to do our choir. Suddenly we see some cars coming, yelling, yelling, then finally you hear ‘bang, bang, bang, bang, bang’,” he recalls. Then he felt bleeding on his leg and realized that he'd been shot.

Papa Senita recuperated from his gunshot wound. But mentally, he was still struggling. He didn’t want to leave his house and got jumpy when he heard a loud noise.

One day, Papa Senita went to get coffee at the local 7/11 store. When a group of kids who recognized him from home started yelling hello, he suddenly felt disoriented and scared. He got back into his car, locked the doors, and drove away. The next thing he knew, he was in Gilroy, about an hour’s drive down the 101, calling his wife from a pay phone to say that he didn’t know where he was, or how he’d gotten there.

“It was very, very scary,” he says.

Addressing Stigma

A doctor later explained that he’d experienced severe PTSD. Papa Senita says the incident left him a little lost. Mental health issues aren’t often discussed in his community. “It’s a curse in Tonga.”

Papa Senita’s wife Appolonia Uhila goes by the nickname Mama Dee. She’s a long-time health advocate, and she recognized that Papa Senita needed help. “We were all worried about the wound... But the mental health is not dealt with.” Particularly in her community, where she says it's “taboo” to talk about this topic.

She called San Mateo County’s behavioral health services to ask about mental health support for Papa Senita. To her surprise – and annoyance – she was given an 800 number to call.

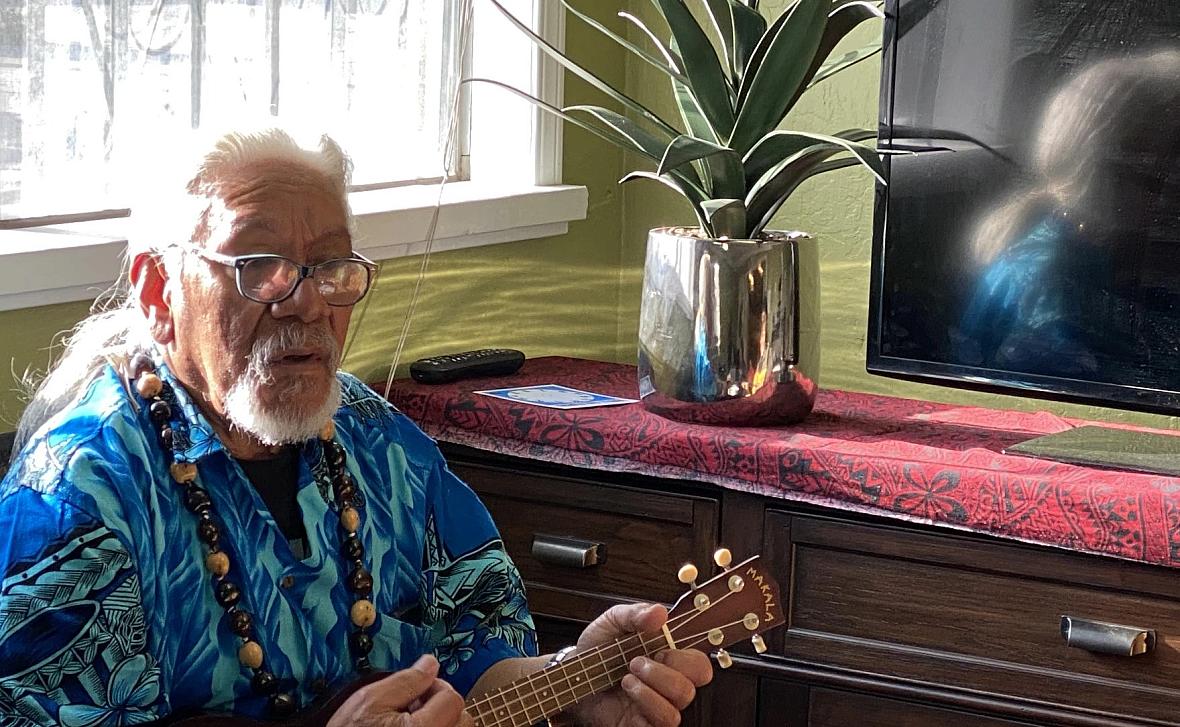

Mama Dee is an experienced community leader and former Commissioner on Aging for San Mateo County. Samoan by birth, she’s advised the county on culturally-appropriate solutions to health issues.

But it wasn’t until her husband was shot, and experienced PTSD, that she really recognized the need for mental health services for Pacific Islanders in the US.

Mama Dee began a search for more local support. With her help, Papa Senita was offered weekly counseling and medication from East Palo Alto’s mental health services. It’s known locally as ‘the third floor’ as that is where the team is located in the behavioral health building.

Cultural Connections

However, something no doctor prescribed also helped him recover. With some fellow musicians, he formed The Third Floor Band, and started visiting sick or isolated seniors from his community. On these hospital or home visits, the band would perform traditional songs and music.

Papa Senita and Mama Dee’s daughter Shanna ‘Uhilamoelangi explains: “They were all Polynesian elders and people that just miss home.” Papa Senita adds that many of the seniors are over 80 and at a point where they don’t really talk any more: “When we go there, I ask: ‘Do you remember a song when you were a little willy wonk?’ They sing the song. They cannot talk but they sing!”

While this also helped to improve Papa Senita’s mental health, Shanna ‘Uhilamoelangi says her mother was frustrated by the lack of appropriate mental health support offered to her community.

Mama Dee began to volunteer and work with the mental health department on getting contracts, including one with East Palo Alto’s Office of Equity and Diversity for mental health. The aim is to provide culturally-sensitive, language appropriate support at grassroots level.

Mama Dee is co-founder with Papa Senita of Anamatangi Polynesian Voices in East Palo Alto. It was set up in the late 1990s to include community views in local policy making. She also lobbied the county to set up a wellness center in 2009, where Pacific Islander seniors and others can go to sing, share potluck meals and stories.

Mama Dee (second left) and her family are bringing culturally-relevant mental health support to their community.

Liza Ramrayka

Combating Isolation

Programs like this are just one solution to tackling loneliness, which San Mateo County declared a health emergency in February 2024. It was the first in the nation to do so. This follows an advisory from the U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy in May 2023 that urged governments to prioritize strategies which promote social connection - to avoid increased risk of medical conditions such as heart disease, stroke and depression.

Leafa Taumoepeau runs the non-profit health and education organization Taulama for Tongans. She says isolation and poor mental health were a problem even before Covid required people to isolate. It’s why she and her volunteers visit churches attended by Pacific Islanders. “We talk a lot about behavior, our mental health, the things that affect us, the things that we need, where we need to go to get the help that we need,” she says. “We try to de-stigmatize mental illness, because we’re culturally one of the groups of people that stigmatize mental health. And I think it’s because of lack of education, our inability to understand what it is.”

Taulama for Tongans’ weekly video meetings help isolated seniors stay connected.

Liza Ramrayka

In 2018, Taulama for Tongans created a program to address senior isolation. It’s called Ngatuvai, named after a flower that becomes more fragrant as it blooms and ages. Before the pandemic, participants in the program would get together in person to share a meal, learn about mental wellness, dance, do crafts and play games. Lockdown put a stop to these events so Taulama moved the meet-up online to keep social interaction going. These Wednesday morning Zoom meet-ups attract dozens of Pacific Island seniors each week. A combination of community chat, mental wellness advice and gentle exercise like chair yoga, the aim is to give seniors – with their children or grandchildren out of the house all day – a social connection they wouldn’t otherwise have.

The session is also broadcast on Radio Tonga VTF USA and streamed via Facebook Live, attracting listeners and viewers beyond the Bay Area, from Seattle to Salt Lake City as well as in Tonga itself.

Regular Fehi Hansen looks forward to seeing her friends each week: “I think this is good for me to have something special, to be there, to look at you guys.”

Improving Data; Sustainable Funding

While these programs offer effective solutions to the issue of mental health among Pacific Islander seniors, good data remains an issue. According to latest research, 42% of Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander adults have trouble accessing mental health services. But that data’s still aggregated.

California’s Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) provides dedicated funding to transform behavioral health systems. San Mateo County received an annual average of $41.2 million, for five years through fiscal year 2022-23. But only 5% of this is budgeted for new approaches and community-driven best practices.

Says Tamaupea: “I always believe that the work that we do is an extension of what the county should do for its people. And they can't do it, but we can. So I want to see little groups like ours, like Mama Dee’s, be funded not just once in a while, but become regular.

She wants to see homegrown solutions, like Papa Senita playing ukulele with his granddaughter and singing familiar songs to fellow seniors, as a common, well-funded part of mental health services.

“Those are the people that brought us here. Those are the people who braved the separation, who braved the inability to understand the language, who found the food very strange. These are the people that sacrificed for us.”