Part III: For evicted people, homelessness often follows

The story was originally published in CT Mirror with the support from USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 National Fellowship and the Kristy Hammam Fund for Health Journalism.

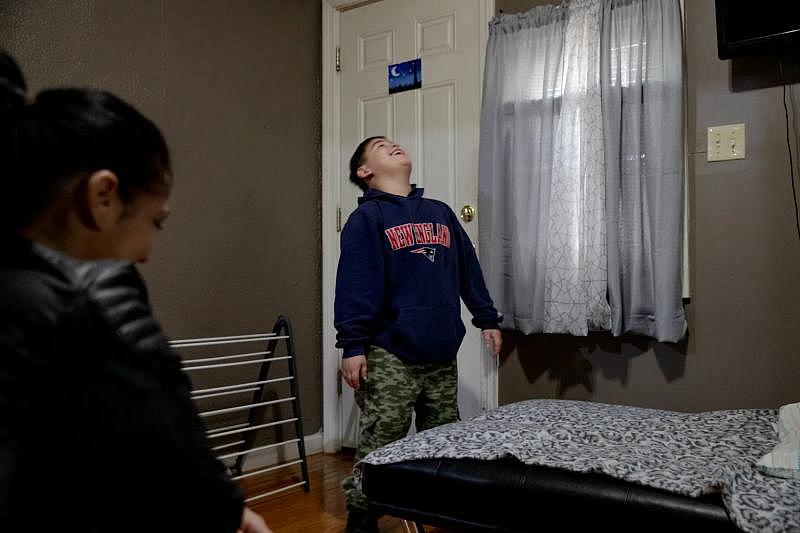

Elizabeth Rodriguez, her son, Mikey Rodriguez, 8, and teenage daughter temporarily stay at her sister’s place after being evicted in June. Rodriguez said Mikey is scared, often asks her when they can go back home and cries at night. YEHYUN KIM / CT MIRROR

YEHYUN KIM / CT MIRROR

Click here to read the story in Spanish.

When Elizabeth Rodriguez tells her 8-year-old son that she doesn’t have any of his baby pictures, not even one or two, she starts to break down.

A pained look crosses Mikey Rodriguez’s round face, and his eyes well up, but he blinks hard and throws an arm around his mother’s shoulders.

The baby pictures, Mikey’s toys, the family’s furniture, the tokens of Elizabeth’s father’s military accomplishments — just about everything is gone. When they were evicted and their belongings were thrown out of the house, rain damaged everything beyond repair.

“It’s OK, Mom. Don’t worry,” Mikey says, his eyes starting to drift to the kids playing soccer across the field at his Bridgeport elementary school.

Their landlord filed to evict Elizabeth in January, and after a series of court filings, the family had to leave their apartment in June. After that, they became homeless, and it’s been months since they had a stable place to live.

For a while, Elizabeth slept in her car while two of her kids — ages 8 and 14 — stayed at her sister’s. Her 19-year-old son stayed at another family member’s house. Mikey asked to start sleeping with a nightlight again.

He slept on a padded pallet on the floor and struggled to get enough sleep because sometimes, he explained, his head would fall off the padding and hit the floor.

“Every morning I wake up with a cramp in my neck,” he said.

Since then, his family bought him a futon.

Elizabeth stayed in her car for weeks and saw her kids after school or on the weekends in public spaces. That lasted until a stomach virus, kidney problems and heart failure forced her to start staying at her sister’s, too. Initially, she was OK with the kids staying at her sister’s. But she worries that with another adult staying in the apartment, her sister would get in trouble with her landlord.

“I don’t want her to lose her apartment,” Elizabeth said. “That apartment is all my kids have. … It’s unsettling.”

Eviction has been shown to lead to homelessness.

Families often become what’s referred to as “literally homeless,” or living in a car, shelter, or outside or if they’re “doubled up,” or couch surfing (sleeping on a friend or relative’s couch). Over the past two decades, several regional and at least one national study have cited data that showed between 14% to 47% of families experiencing homelessness had been evicted.

Eviction has a wide range of negative effects on a family, and homelessness makes it worse, experts said.

If families become homeless after an eviction, they can have worse health outcomes and heightened mental health concerns. It can also put kids at higher risk of getting involved with the juvenile justice system, research shows.

“We see firsthand the stress that is placed on families when they come into shelter,” said Kellyann Day, chief executive officer at New Reach, a homelessness prevention nonprofit with offices in Bridgeport and New Haven.

“So, if we can keep people stably housed before they have to enter crisis services, that has such a huge impact on the entire family. Even though they’re experiencing the instability of a potential eviction, the impact of becoming homeless is 10 times worse.”

Homelessness rising

Homelessness occurs soon after a family has exhausted other social services, and it has several effects on physical and mental health.

Over the past year, the state’s 211 hotline, which helps coordinate connections to service for families in need, has received an average of more than 1,000 requests for help with housing-related issues each day. About 110,000 of those have been specifically about shelter access, according to data from the United Way of Connecticut.

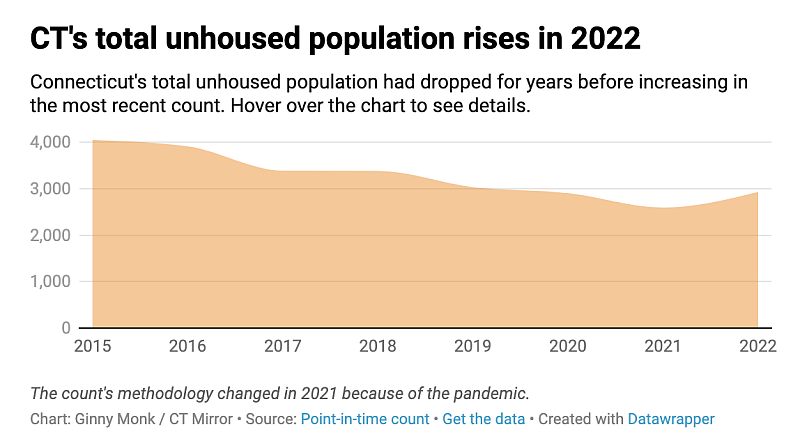

And homelessness increased in 2022 for the first time in nearly a decade, according to an annual count of the unhoused population. The number rose by about 13% — from 2,594 to 2,930, likely a result of economic fallout from the pandemic, inflation and a lack of affordable housing, experts said.

The count often misses many kids because they’re more likely to be staying with friends or family. Sometimes, parents will try to keep their homelessness hidden, fearing that the state will take their children.

The count's methodology changed in 2021 because of the pandemic. Chart: Ginny Monk / CT Mirror Source: Point-in-time count

Still, the 2022 count noted at least 558 unhoused minors in Connecticut. And a 2020 report that focused on youth homelessness found that there were 7,823 people under 24 experiencing homelessness or housing instability in Connecticut.

The wait list of young adults looking for shelter is longer than is typical, said Stacey Violante Cole, director of operations and Right Direction: Homeless Youth Advocacy Project at the Center for Children’s Advocacy.

“In my experience, I'm getting more calls about minors and getting more young adults who are on the verge of homelessness or are experiencing homelessness,” she added.

Evicted in Bridgeport

The Rodriguez family was able to save very little from their Bridgeport apartment. Mikey managed to climb the fence and launch his bike back over, but he broke the chain in the process.

Much of their clothing was coated in mold after the rain. The clothes they kept were just what she could fit in the bags and baskets she packed before the eviction date.

The landlord filed an eviction case in January, and the case dragged on for months. Elizabeth enlisted the help of the Connecticut Fair Housing Center. She wanted to move anyway, she said, although she wanted more time to find a new place.

Her income came partly from Social Security she receives for her medical disabilities, largely related to heart failure, and part-time work “here and there,” she said.

Her housing choice voucher was one of the biggest concerns with the eviction. If a tenant is evicted for not paying their rent, they also lose their voucher, which pays a portion of the rent.

Her family lived in the same place for most of her childhood. Her first experience with eviction was when her neighbor was being evicted and killed himself in his apartment. Elizabeth's teenage daughter found him, she said.

“My anxiety’s not well,” she said. “My mindset is in a different place. I'm supposed to be worrying about my health and taking care of my health. All I worry about every single day is that my son's gonna say to me again, ‘Mommy, I want to move. I want to go home.’”

Rental assistance

Everyone she knew in her building applied for rental assistance through the state’s UniteCT program. Elizabeth says her landlord told her she should apply.

She received rental assistance with UniteCT, but her landlord pushed forward with the eviction. The rental aid came through two days after she was evicted, she said.

The eviction filing says she didn’t pay December rent.

She says she’d paid the rent and that she just owed late fees.

She says the papers were delivered to the wrong address, so she missed her first court appearance. Tenants often miss court appearances, which typically results in a ruling in favor of the landlord.

That’s what happened in Elizabeth’s case, but her legal aid attorney asked for the case to be reopened, and in mid-November, her housing voucher was reinstated. She’s looking for a new apartment but hasn’t updated her children on the details of the search.

“I want to surprise them,” she said. “I’m going to just pull up to the place and tell them.”

Mikey laughs with Elizabeth while organizing a sofa bed in her sister's living room. Mikey and Elizabeth sometimes sleep together on the sofa bed. YEHYUN KIM / CT MIRROR

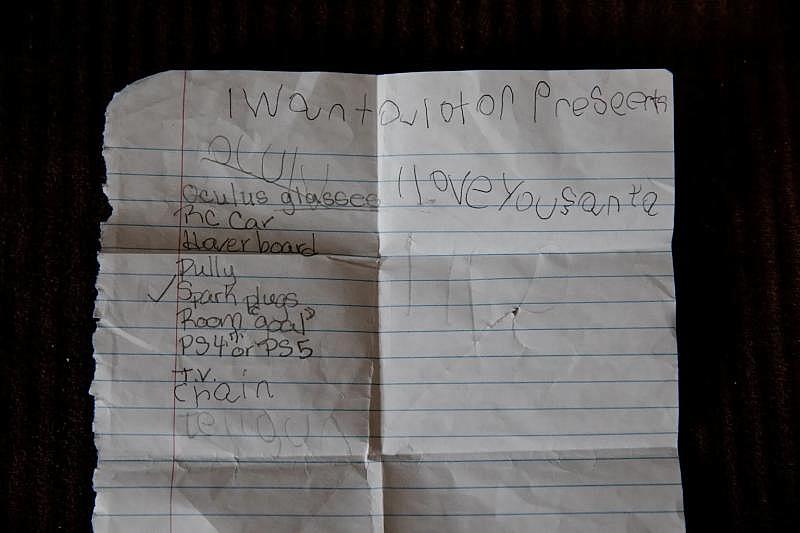

It’s been weeks, though, and she still hasn’t found a new apartment. Mikey asked for a new bed frame for Christmas and told her to use the money she would have spent on toys toward the cost of a new apartment.

He doesn’t know his only gift this year cost just $5.

Homelessness prevention, support for kids

Eviction prevention is one of the primary ways that New Reach, a Bridgeport-based nonprofit, fights homelessness. The nonprofit has programs that address housing needs, crisis services and eviction prevention.

New Reach case workers help connect people being evicted with legal aid attorneys who can represent them in the court case. Case workers also help talk with landlords to come up with a plan for tenants to pay their back rent. Sometimes, it helps to have a third party involved to resolve issues, New Reach’s Day said.

New Reach has a series of questions and statistics that help them determine who is most likely to become homeless following eviction, Day said.

“We have some predictive characteristics — a scale that we tend to use — but we also know that if a single mom of color comes to us and is being evicted, just by virtue of being a single mom of color, she is likely to become homeless,” said Meredith Damboise, chief quality and compliance officer at New Reach. “So that in and of itself is the biggest predictor for us right now.”

Other factors include whether a person has been homeless before or experienced housing instability as a child, Damboise said.

The Connecticut Youth Services Association is partnering with other groups to form a support system aimed at helping children who are experiencing homelessness.

“Connecticut has a system set up for anyone over 18,” Violante Cole said. “What we don't have in Connecticut is a great system for minors who are experiencing housing instability and homelessness.”

Sometimes those kids become homeless because they are escaping violence at home, and in some cases they don’t want to ask for help because they don’t want child welfare to be involved in their lives.

The state Department of Children and Families has some housing services in place for families with open cases, including supportive housing that offers case management as well as an affordable place to live.

Elizabeth Rodriguez and Mikey sit in the living room of her sister's place, surrounded by their belongings. She had to throw away many important belongings after damage from rain during the eviction. YEHYUN KIM / CT MIRROR

Violante Cole, of the Center for Children’s Advocacy, and Erica Bromley, the juvenile justice liaison at the Connecticut Youth Services Association, are working to ensure that kids don’t enter the juvenile justice system because of housing instability.

The nonprofits have developed a case conferencing process that helps connect children to the services they need, including housing. The process has started in

Stamford, Bridgeport, Manchester and New London. Organizers are working to branch out to Hartford.

Research has tied youth homelessness to an increased chance that they will spend time in prison or jail.

They may be arrested for “survival crimes,” such as stealing food to eat or trespassing into a warm building, according to a policy brief from the Coalition for Juvenile Justice.

And youths who run away from home are supposed to be directed to the Youth Services bureaus. Recently, the state shifted its approach. Previously, children who ran away from home were referred to the juvenile court system, Bromley said.

The new approach aims to provide them services and keep them out of the juvenile justice system. Research has shown that children who enter the system tend to have worse outcomes in several areas including education, career, health and mental health.

“If they've run away and they're not going home, then they would be a minor who's homeless or has housing instability,” Bromley said. “So, we're trying to also tie that in.”

A list of gifts that Mikey Rodriguez, 8, wants for Christmas

Parallel to these efforts, Violante Cole and others at her organization are trying to convince lawmakers to “beef up” the rights of youths and ensure they have access to health care and mental health services. Last session, the legislature made mental health care for children a priority.

Health impacts

Elizabeth said her kids’ mental health has suffered since they started experiencing housing instability.

“It just makes me feel really bad because, you know, Mikey was so sad the other night, and I couldn't make the situation better, and I'm supposed to,” she said. “He’s tired of sleeping on the floor.”

Studies have estimated that about 25-30% of people experiencing homelessness also have a serious mental illness. And, in turn, homelessness can create or worsen mental health problems.

The stress of homelessness can foster anxiety, depression, trouble sleeping, fear and substance use, research shows. Both of Elizabeth's kids have started therapy since the eviction, she said.

Elizabeth’s 14-year-old daughter, who asked not to be identified in this story, struggled with the loss of her own private space.

Medications of Elizabeth Rodriguez, who is waiting for transplants of a heart and a kidney.

“She has three children she needs to worry about. Now she's on the street,” the teenager said of her mother. “And that's not fair, because I haven’t slept in a bed in a w

hile.”

The teen also says it’s impacted the amount of time she gets to spend with her friends (although her mother says she sees her friends frequently). One Friday night in October, her brother's elementary school kept the playground and soccer field open late for the kids. She walked around the field with friends, bringing one over to her mother to ask if she could go to her friend's house for a sleepover.

“I’ll do aaaanything,” she begged. When the answer was no, she huffed, “You always used to let me go before all this happened.”

She worries about her mother’s health, too.

Her mom has heart failure and is on a waiting list for a transplant. Elizabeth’s kidneys are damaged as well, and her doctor plans to request a kidney transplant in addition to the heart in January.

Elizabeth and Mikey Rodriguez go through his Christmas gift wish list. Mikey told Elizabeth that she doesn't have to get him the Oculus glasses because they would need that money to get a place, she said. YEHYUN KIM / CT MIRROR

She was in the hospital for several days in October with high blood pressure and a stomach virus. The kidney problems kept her from getting a heart procedure done. The stress of the eviction exacerbated her preexisting health conditions, she said.

But staying in the hospital was better than sleeping in her car, she told the CT Mirror, one October day while she sat in the Bridgeport hospital bed, gears whirring to help her sit up to eat.

“I’m only 42, and my heart, it's like slowly stopping,” she said. “It doesn't get better. It just stays like this or gets worse.”

Her health problems also made it impossible for her to move the family’s heavier items such as furniture out of the house, she said. The court marshal and state-hired movers had to come remove their belongings.

Despite her health problems, Elizabeth stayed focused on her kids, even when she was hospitalized. A couple of days before Halloween, she sorted through bags of candy, stickers and costume supplies that her sister brought, ensuring both of her younger children would have all the ingredients for a happy night.

“I brought them into this world,” she said, her voice hoarse and weak after her illnesses. “They didn't ask to be in this world. How dare I put them through something that they shouldn't go through?”