Part II: How one ninth-grader navigated new obstacles after her family was evicted

The story was originally published in CT Mirror with the support from USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 National Fellowship and the Kristy Hammam Fund for Health Journalism.

Loryann Pisani takes a break on moving day in Bloomfield. “This is why I don’t like moving. After that, I’m not moving for a while.” YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

Click here to read the story in Spanish.

High school was going to be hard enough for Loryann Pisani.

Loryann Pisani, 16, holds her sister, Bethany Cortes, 2, while adults move their belongings to move to a new place in West Hartford. “Kind of nervous,” Loryann said. “It’s new everything.” YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

Loryann, 16, knows she has trouble adjusting to change. It’s easy to make her emotional, to make her cry, she explained. She’s developmentally and intellectually del

ayed, meaning she’s a bit behind her peers and struggles with anxiety, certain academics and athletic activities.

So, with ninth grade looming, she and her mother, Kristine Pisani, worked to prepare for as much as possible.

Loryann spent most of her summer at what she thought would be her future high school in Bloomfield, learning where her classes would be, how to use her locker and getting comfortable with her new surroundings.

But in August, just a couple of weeks after she finished her summer-long high school orientation, her family was evicted. And after weeks of trying to find

a new home in Bloomfield that fit their budget and size needs, and that had a landlord who would rent to someone with an eviction record, her family moved to a new school district in West Hartford.

That left Loryann starting high school in a new town with new peers, unprepared for a new environment.

“It’s kind of scary,” Loryann said. “I get very emotional when things are scary. It’s like I’m sad when things get scary.”

The switch made it hard to concentrate as she tried to figure out her new surroundings.

Her mother Kristine said she heard her daughter crying a few times in the weeks before they moved.

“She’s asking me questions,” Kristine said. “’Where’s my room going to be?’ ‘How am I going to get to see grandma, grandpa?’”

Loryann Pisani, 16, holds her sister, Bethany Cortes, 2, while adults move their belongings to move to a new place in West Hartford. “Kind of nervous,” Loryann said. “It’s new everything.” YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

Kristine’s mom Lori Agnew now lives with them during the week, sleeping on their couch, to help drive the kids to and from school and doctor’s appointments. She also cares for 2-year-old Bethany Cortes, Loryann’s younger sister, who still hasn’t been able to get into a day care.

Kristine and Justin Cortes, Bethany’s father, co-parent their daughter at the apartment they share.

The challenge after the eviction was finding a place for the four of them.

Loryann spends some weekends at her father’s house, but he doesn’t live with the Pisani family.

Disruptions

Educational and child care disruptions because of housing instability are growing increasingly common. The disruptions are known to have immediate and long-term impacts on kids’ mental health, academic success and social lives, according to mental health and housing experts.

For Loryann, the most immediate mental health concern when she was uprooted from her school system was the heightened anxiety. This is common among children who have to switch schools, particularly when the switch is abrupt, mental health experts said.

“It’s a lot to take in,” Kristine said. “It’s a very big toll on us. And it’s an unfortunate situation.”

Kids thrive on routine, and school tends to be a big part of that routine. When it’s disrupted, it can be distressing, said Jason Lang, chief program officer at the Child Health and Development Institute, a Farmington-based nonprofit research organization that helps train other pediatric and mental health providers in Connecticut.

“If they have to move somewhere where they need to go to a new school, it’s another huge disruption in a child’s life,” Lang said. “You know, they lose all their teachers, all their friends in that school, and then have to go through the process of making new friends and learning a new school, as well as having a new place to live.”

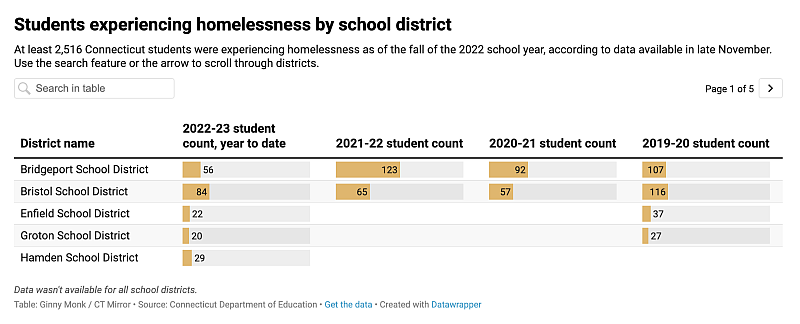

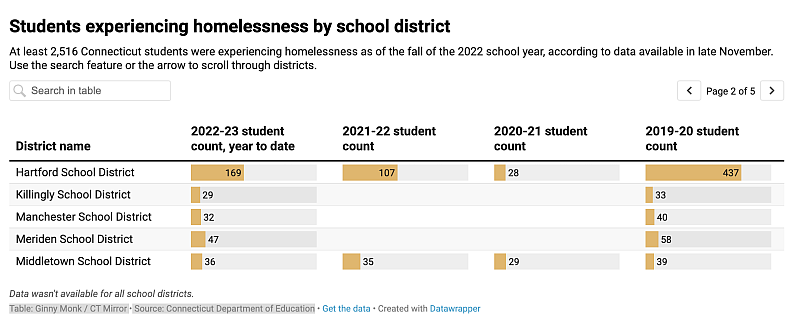

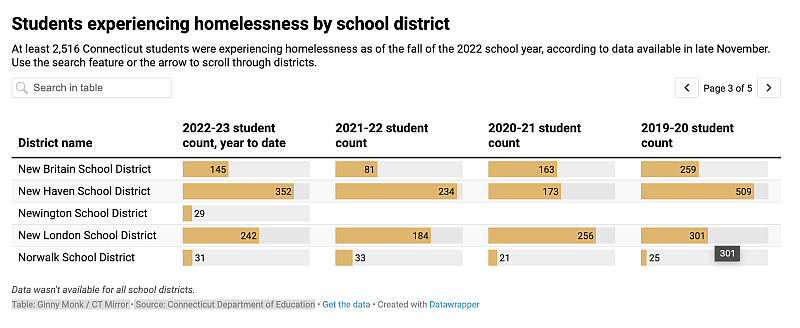

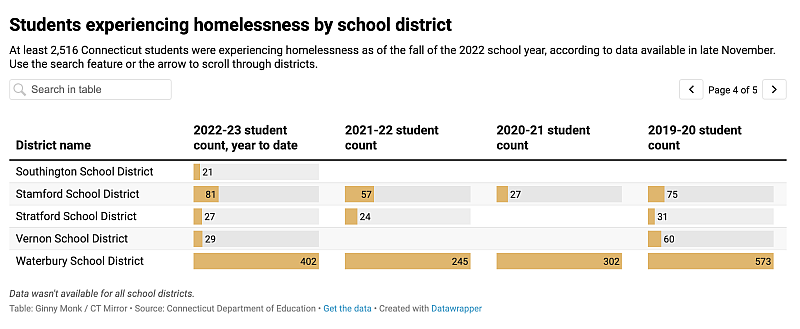

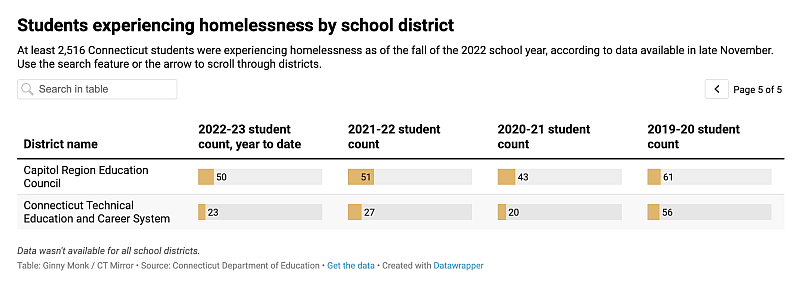

Table: Ginny Monk / CT Mirror Source: Connecticut Department of Education

Impacts

A 2013 study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston showed that kids in the area whose families experienced housing instability because of mortgage foreclosures also tended to have lower test scores in reading and math.

Housing instability has been tied to chronic absenteeism. The state Department of Education is working with school districts to implement a system of interventions for families to ensure kids go to school.

Table: Ginny Monk / CT Mirror Source: Connecticut Department of Education

The federal McKinney-Vento Act requires that children experiencing homelessness get proper access to education. The law requires that children have a choice of school and services comparable to what they received before they became homeless.

It also bars states and local governments from enacting policies that keep children experiencing homelessness from attending school or from segregating homeless students from their classes.

The Connecticut Department of Education reports there are 2,516 students experiencing homelessness to date in the 2022-23 school year, with an absenteeism rate of about 85%.

Table: Ginny Monk / CT Mirror Source: Connecticut Department of Education

Loryann moved from one apartment to another, never experiencing homelessness. The McKinney-Vento Act also only includes the school year that’s going on when homelessness occurred, so the act didn’t apply to her.

The timing of an eviction could also mean kids miss deadlines to sign up for after-school programs and extracurricular activities, said Gary Steck, chief executive officer at Wellmore Behavioral Health in Waterbury.

“Just the idea of witnessing your family being evicted is probably something that most people will vividly remember as adults,” Steck said. “We’ll say it was a pivotal event for them. Not just in the sense of it being stigmatized, but also the sheer shock and potential. So, as it relates to education, you would expect to see lower rates of attendance and lower academic outcomes.”

Table: Ginny Monk / CT Mirror Source: Connecticut Department of Education

For kids like Loryann who need special services and have individualized educational plans (more commonly called IEPs), the transition can be even

tougher. They have to develop a new IEP with their school, develop new relationships with educators and set up access to services at their new location, said Maria Morelli-Wolfe, an attorney specializing in education at Greater Hartford Legal Aid.

This year, the system for developing those IEPs is new. It’s meant to be more streamlined and easier to navigate, and it allows easier online access to the information for parents.

Table: Ginny Monk / CT Mirror Source: Connecticut Department of Education

But it was a fresh process for families, including Loryann's, to learn.

The eviction

Kristine has always placed high value on education for her kids. In Bloomfield, the teachers, principals and even members of the school board knew her, she said.

“When it comes to education, I’m not going to be quiet. You’re going to hear me,” she says often.

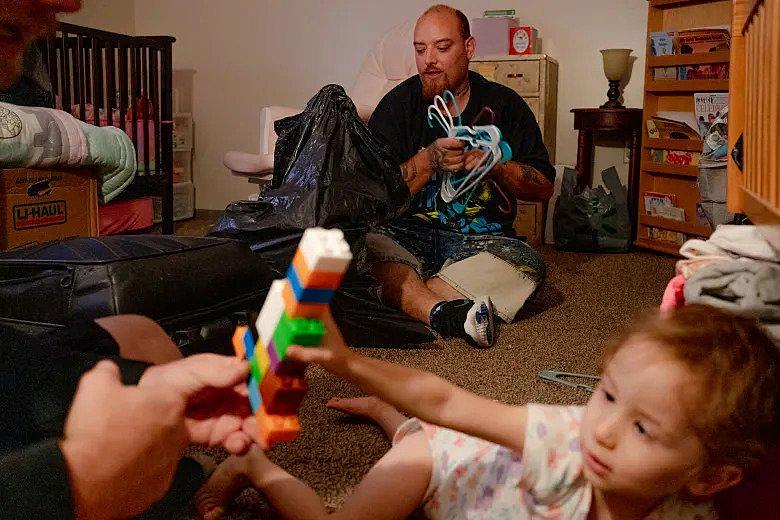

Justin Cortes packs hangers while his friend, Nathan Cook, hangs out with Cortes' daughter, Bethany Cortes, 2. The family is still looking for child care for her near their new place. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

Her mom did the same for her, she said. Kristine had some similar developmental delays that her daughters now face, and her mom helped her navigate them. Now, Kristine works in early childhood education.

Kristine was also one of the more outspoken members of the Wedgewood Tenants Union at the Wedgewood Apartments in Bloomfield. The group organized to protest poor living conditions. At Kristine’s apartment, there were problems with sewage, a leak in the ceiling and a gas leak. The CT Mirror confirmed conditions through in-person visits to the building and reviewing photographs and documents provided by town officials and residents. Interviews, photos and documents confirm the conditions.

The leak caused what appeared to be mold to spread in rugs and onto Loryann’s backpack. Her younger sister Bethany, who likes to roll on the carpets, got an infection that caused swollen red bumps across her cheek.

Loryann's room before moving out is decorated with photos of her family and friends. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

Kristine believes she and her family were targeted for the eviction because of her union activities.

The family was evicted in August for missing rent payments. Kristine had COVID-19 at the start of the year and couldn't go to her job at the early childhood education center. She also had a foot injury that left her unable to work. She fell two months behind in rent and was served an eviction notice.

She said she repeatedly contacted her landlord to try to work out a payment plan but was forced to find a new place to live after a court mediation agreement in July.

Despite the problems at their Bloomfield apartment, it would have been easier on the family to stay. Moving was expensive. In Bloomfield, they knew thei

r neighbors. Public transportation was easier. They were just a couple of minutes away from Kristine’s mom.

Loryann watches neighbors and friends who came to help the family move out. "This is why I don't like moving. It's a lot of things going on just one day. It's one of those crazy days," Loryann said. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

But still, in mid-August, Kristine started packing up the house — the mediation agreement in court stipulated that she leave by Aug. 22. She let Loryann pack her own room in an attempt to give the teenager some measure of control over the situation.

The family had trouble finding a new apartment with an eviction on their record, a situation that was made more difficult because Kristine wanted to stay in Loryann’s Bloomfield school district. So she moved as many belongings as she could into a storage unit, booked a hotel room and washed enough laundry for a couple of weeks “just in case.” The hotel room had a free cancellation policy.

Loryann asked if she could bring her Funko Pops, the plastic figurines she collects with her sister’s father, to the hotel. Dozens of them line her bookshelves.

During an eviction, belongings are often damaged or lost. Loryann wanted to be sure that didn’t happen to her Funko Pops or several pieces of her artwork. They made the journey with no problem and once again adorn her new bedroom.

A photo of Loryann Pisani and her mother, Kristine Pisani, hangs in the hallway. "I don't like moving. You have to pack everything," Loryann said. "People keep going in and out the day before moving." YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

They found a new apartment in West Hartford just days before they had to be out of the apartment in Bloomfield.

Effects on the kids

The move has been tough for Loryann, although she’s settling in. She likes that she’s going to the high school her grandmother once attended but still doesn’t want to go outside at night, even to walk the dog in the parking lot, because she’s not yet comfortable enough with the surroundings.

Kristine explained the move to her daughter using an analogy about school. She said the court’s order was similar to a principal’s — you have to do what they say.

“Sometimes you might not like it, but you’ve got to do what your principal says,” she said.

Her day in court was emotional. She brought a file full of photographs and emails documenting the condition of her home, but the case was to decide whether she’d be

Loryann Pisani, 16, looks at her family's belongings to be moved at her place in Bloomfield, where she lived her whole life. Her family had to suddenly move to West Hartford after they were evicted. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

evicted based on her missed rent, not to judge the apartment’s condition.

She sat in the court building arguing this with her landlord’s attorney, and by the time she came out, she was in tears.

It proved difficult to find a place big enough for her family. In the end, they had to go from a three-bedroom to a two-bedroom. Her toddler’s clothes are now stored in

her teenager’s room, and the 2-year-old sleeps in the room with her parents, another change in the family's routine.

But through that process, she tried to keep her emotions from her children.

“I’ve got to be strong for my kids,” she said the day they moved their belongings into storage. “What I feel and what I’m going through, I do it behind closed doors.”

New environments

Loryann Pisani takes a math class from teacher Noreen Branley, where she learns how to purchase items effectively. Despite Loryann's concern before moving to a new place, she said she's doing well at her new school. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

At first, finding her classrooms at the new school proved difficult for Loryann, making it hard to concentrate in the first few weeks. At Bloomfield, the summer program had prepared her for this; she’d been shown where her classes were and which paths to take.

“It's big,” Loryann said, wringing her hands. “It's like a maze. Because there's like so many, like, hallways and you have to go through all these doors.”

She repeats that often — the school is big, it’s like a maze. She worries about finding her classes, getting lost, knowing what to do, even after months at the new school.

For some kids, the trauma of an eviction can cause behavioral problems, said Morellis-Wolfe.

Others struggle with disruptions in school-based services.

Leah Gonzalez, right, 16, one of Loryann's best friends, calls her parents to have a small birthday party for Loryann. Loryann, left, said she already made three best friends at the new school. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

“The special education teacher has a schedule that she's following. The speech and language pathologist, same thing,” Morellis-Wolfe said. “So if the child isn't present…, they may miss out on some services.”

Because kids’ social lives are so tightly tied to school, a switch at school can disrupt their interpersonal connections, experts said.

It can take time for kids to build that trust back up in new people, Steck said.

“I think that they’re [social relationships] core to who we are as people,” he said. “It goes back to what is that sense of security? How do I get to a place where I feel safe and secure?”

<-- image-carousel-2 -->

Loryann misses her friends at Bloomfield. She’d been in some classes with the kids at Bloomfield since elementary school.

Loryann, center, 16, laughs with one of her best friends, Leah Gonzalez, 16, during lunch time. "At first, it was emotional when I had to move," Loryann said. "Now it's good. It's better." YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

And it’s still hard. At a recent United Sports soccer game in West Hartford, she played several matches, cautiously running, only occasionally kicking at the ball when it rolled outside of the group. The United Sports helps her get used to more physical activity with other kids who are developmentally delayed.

When it came time to play against Bloomfield, Loryann was “getting in there,” her grandmother said. She knew the other kids, and was more comfortable with them.

But she’s adjusting. She joined the choir and just performed in her first concert — a Broadway-themed show. She’s making friends and had a mixture of kids from West Hartford and Bloomfield at her 16th birthday party.

She also got invited to a homecoming dance, which would have been her first date if the boy hadn’t gotten sick ahead of the event. As she planned what to wear, she worried over whether his hands would feel sweaty when they slow-danced.

Loryann, 16, leads a social skills class at Hall High School in West Hartford. It was her 16th birthday, and teachers and friends sang a song and gave her presents, including the hairband. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

But, it was a welcome shift from worrying about where she was going to live, she said.

“It’s kind of nice,” she said.

"Notice to Quit," a multi-part examination of evictions in Connecticut and their effects on children and families, was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 National Fellowship and its Kristy Hammam Fund for Health Journalism. This project also was supported by the Center’s Engaged Journalism Initiative.